1. Background

Aluminum toxicity has been a significant concern in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (1, 2). Chronic excess aluminum can lead to various health issues, including low-turnover osteomalacia, decreased levels of parathyroid hormone, anemia, microcytosis, and increased requirements for erythropoietin (3, 4). These manifestations were frequently reported in the 1970s and 1980s among patients who were inadvertently exposed to low levels of aluminum in dialysates or who were undergoing chronic treatment with aluminum-containing phosphate binders (5). More acute symptoms, such as encephalopathy and seizures, were historically associated with significant contamination of dialysate water (6, 7). Due to reduced use of aluminum-containing phosphate binders, aluminum-related diseases are now considered much rarer. Serum aluminum levels in patients with normal renal function typically remain below 6 μg/L (8). The acceptable serum aluminum level should be less than 20 μg/L. If the serum aluminum level falls between 20 and 60 μg/L, it is important to identify and eliminate all sources of aluminum.

Patients undergoing dialysis are at a high risk of aluminum accumulation for several reasons: The long-term use of phosphate binders (in the past), the incomplete elimination of aluminum by the kidneys, and exposure to dialysis materials that contain aluminum (9). One effective method for removing toxic elements like aluminum from the body is chelation therapy, which can be administered either as a treatment alone or in combination with other treatments. The National Kidney Foundation’s Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF KDOQI) recommends the use of deferoxamine (DFO) for managing aluminum overload in dialysis patients (10). Deferoxamine toxicity is dose-dependent, leading researchers to investigate the optimal dosing for effectively treating aluminum overload (11). According to the most recent KDOQI clinical practice guidelines, the recommended standard dose of DFO is 5 mg/kg of body weight (10).

2. Objectives

In response to the emergence of new clinical symptoms in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis between May and July 2024, and the potential risk of aluminum poisoning, this study was conducted. The present study aimed to investigate these cases and compare the treatment outcomes of DFO combined with either peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis. In this retrospective observational study, patients’ demographic data were extracted from their electronic files. The frequency of signs and symptoms and the efficacy of treatment protocols, based on the national guideline for aluminum poisoning treatment, were investigated.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

Although serum aluminum levels are not routinely checked in ESRD patients, due to unusual neurological symptoms and hypotension observed in many peritoneal dialysis patients between May and July 2024, aluminum poisoning was considered as a differential diagnosis. This retrospective observational study was conducted on all patients with end-stage kidney disease on chronic peritoneal dialysis under the supervision of the Peritoneal Dialysis Unit of Khurshid Hospital, Isfahan. Patients’ demographic data were extracted from the Peritoneal Dialysis Registry. The frequency of signs and symptoms and the efficacy of treatment protocols, based on the national guideline for aluminum poisoning treatment, were investigated. All patients underwent a complete examination, and a comprehensive history was obtained. Serum aluminum levels were measured using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) at Nobel Laboratory in Isfahan with a Perkin Elmer atomic device. Elevated serum aluminum levels confirmed aluminum poisoning. The duration of the study was 10 months (May 2024 to February 2025). This study was ethically approved by the Research Council and Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran (IR.ARI.MUI.REC.1403.198). Patients were selected from Khurshid Hospital Peritoneal Dialysis Center.

3.2. Study Groups

Initially, based on serum aluminum levels, patients were divided into three categories:

1. Aluminum level 20 - 60 μg/L

2. Aluminum level 60 - 200 μg/L

3. Aluminum level > 200 μg/L

We did not perform DFO challenge tests because patients were symptomatic and had serum aluminum levels > 60 μg/L. Patients with serum aluminum > 200 μg/L did not receive DFO, based on clinical safety guidelines. Deferoxamine was administered at 5 mg/kg intramuscularly weekly for eight weeks, and serum aluminum levels were then reassessed. Treatment continued until aluminum levels reached < 60 μg/L. Patients receiving both hemodialysis and DFO underwent hemodialysis 6 - 7 times per week using a high-flux filter for 4 hours per session. Patients not receiving DFO underwent routine hemodialysis three times per week. In peritoneal dialysis patients, after DFO injection, the abdomen was kept empty for five hours to optimize chelation efficacy.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 8 software. Descriptive data are reported as numbers and percentages. For statistical analysis, the chi-square or McNemar test was used where appropriate. P-values, confidence intervals (CI), and odds ratios (OR) or risk ratios (RR) are reported.

4. Results

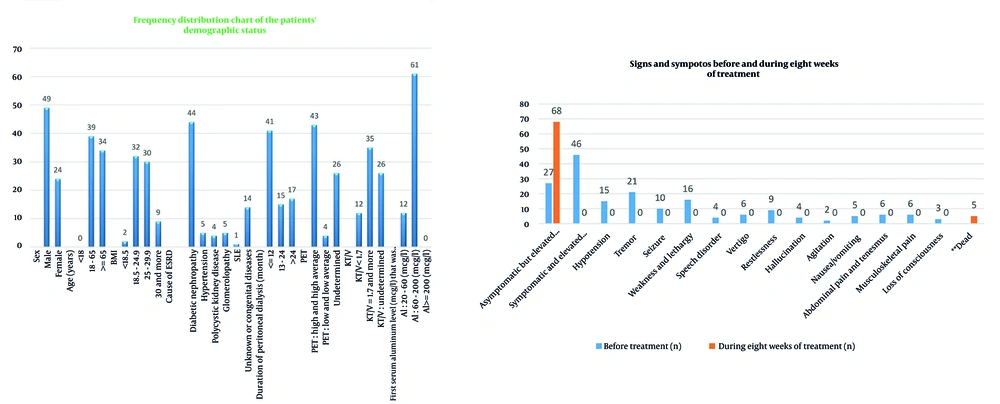

The study included 73 patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis, with 67.1% male and 32.9% female participants. The age distribution was as follows: 53.4% were aged 18 to 65 years, and 46.6% were older than 65 years. Regarding BMI, 43.8% of patients had a BMI of 18.5 to 24.9, and 41.1% had a BMI of 25 to 29.9. The leading cause of ESRD was diabetic nephropathy (60.3%), followed by unknown or congenital causes (19.2%), hypertension (6.8%), glomerulopathy (6.8%), and polycystic kidney disease (5.5%). Most patients (56.1%) had been on peritoneal dialysis for less than 12 months. Based on the peritoneal equilibration test (PET), 59% were classified as "High" or "High Average" transporters. Additionally, 48% had a KT/V ≥ 1.7.

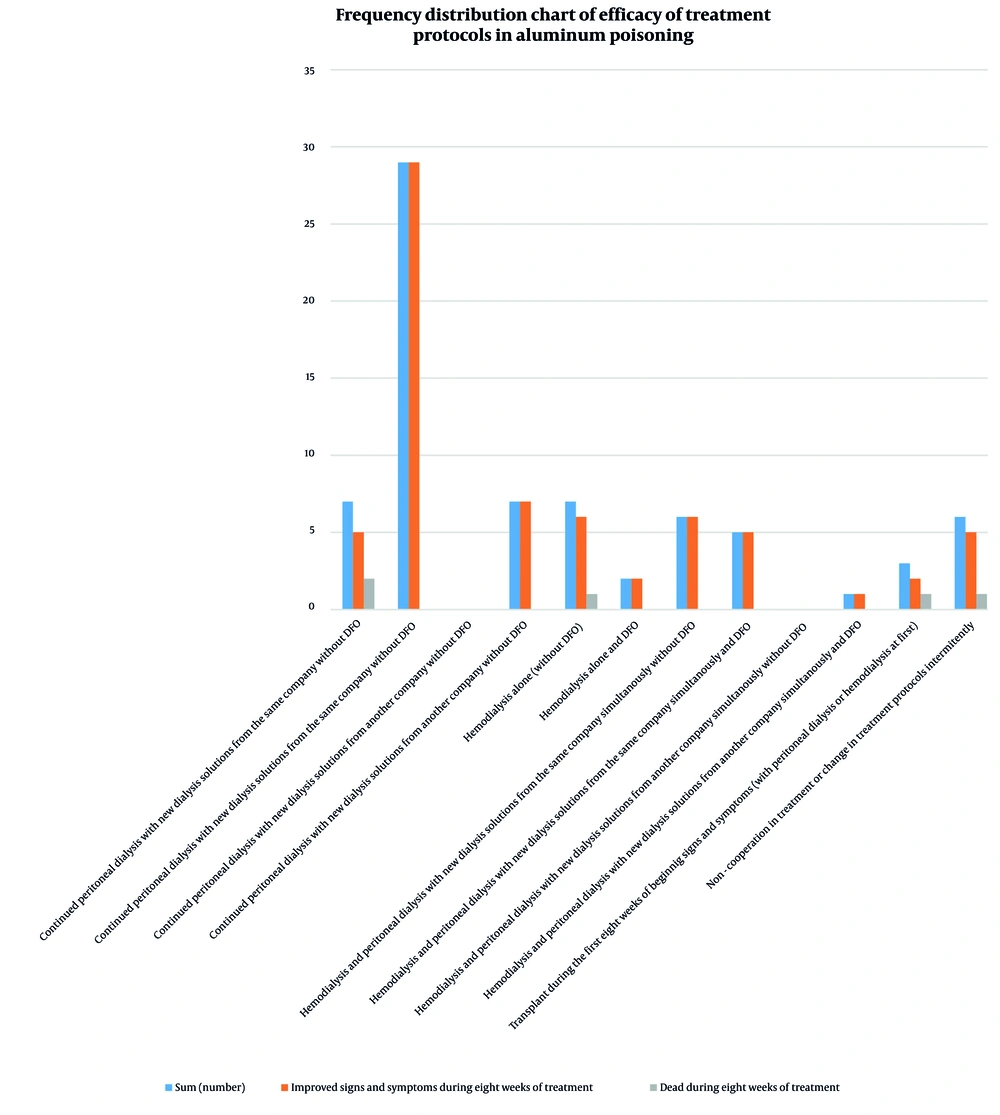

Aluminum levels were between 60 and 200 μg/L in 83.6% of patients, with none exceeding 200 μg/L (Table 1 and Figure 1). Treatment outcomes (Table 2) showed that 29 patients who continued peritoneal dialysis with DFO achieved complete recovery. Positive outcomes were also observed in patients undergoing hemodialysis with DFO. Overall, 68 out of 73 patients (93.2%) showed improvement. There were 5 deaths (6.8%) attributed to poor adherence or absence of DFO treatment (Figure 2).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 49 (67.1) |

| Female | 24 (32.9) |

| Age (y) | |

| < 18 | 0 (0) |

| 18 - 65 | 39 (53.4) |

| ≥ 65 | 34 (46.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| < 18.5 | 2 (2.7) |

| 18.5 - 24.9 | 32 (43.8) |

| 25 - 29.9 | 30 (41.1) |

| 30 and more | 9 (12.3) |

| Cause of ESRD | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 44 (60.3) |

| Hypertension | 5 (6.8) |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 4 (5.5) |

| Glomerolopathy | 5 (6.8) |

| SLE | 1 (1.4) |

| Unknown or congenital disease | 14 (19.2) |

| Duration of peritoneal dialysis (mo) | |

| ≤ 12 | 41 (56.1) |

| 13 - 24 | 15 (20.5) |

| > 24 | 17 (23.3) |

| PET | |

| High and high average | 43 (59) |

| Low and low average | 4 (5.4) |

| Undetermined | 26 (35.6) |

| KT/V | |

| Under 1.7 | 12 (16.4) |

| 1.7 and more | 35 (48) |

| Undetermined | 26 (35.6) |

| First recorded serum aluminum level (mcg/L) | |

| 20 - 60 | 12 (16.4) |

| 60 - 200 | 61 (83.6) |

| 200 and more | 0 (0) |

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; PET, peritoneal equilibration test.

| Variables | Sum (No.) | Improved Signs and Symptoms During Eight Weeks of Treatment | Dead During the First Eight Weeks of Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continued peritoneal dialysis with new dialysis solutions from the same company without DFO | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| Continued peritoneal dialysis with new dialysis solutions from the same company and DFO | 29 | 29 | 0 |

| Continued peritoneal dialysis with new dialysis solutions from another company without DFO | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Continued peritoneal dialysis with new dialysis solutions from another company and DFO | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Hemodialysis alone (without DFO) | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| Hemodialysis alone and DFO | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis with new dialysis solutions from the same company simultaneously without DFO | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis with new dialysis solutions from the same company simultaneously and DFO | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis with new dialysis solutions from another company simultaneously without DFO | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis with new dialysis solutions from another company simultaneously and DFO | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Transplant during the first eight weeks of beginning signs and symptoms (with peritoneal dialysis or hemodialysis at first) | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Non-cooperation in treatment or change in treatment protocols intermittently | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| Sum | 73 | 68 | 5 |

Abbreviation: DFO, deferoxamine.

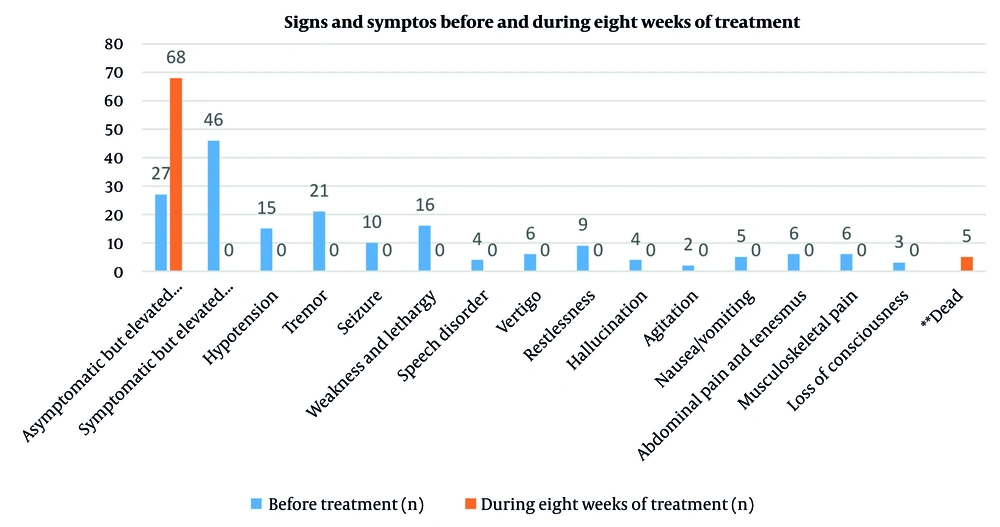

Clinical symptoms (Table 3) such as weakness, tremor, seizures, nausea, musculoskeletal pain, dizziness, speech disorders, restlessness, hallucinations, and agitation were completely resolved. The proportion of asymptomatic patients increased from 37% to 93.2%. Statistical analysis showed significance with a P-value of 0.0017, with CI and effect size reported (Figure 3).

| Variables | Before Treatment | During Eight Weeks of Treatment | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asymptomatic but elevated serum aluminum | 27 (37) | 68 (93.2) | 0.0017 |

| Symptomatic and elevated serum aluminum | 46 (63) | 0 (0) | |

| Hypotension | 15 (20.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Tremor | 21 (29) | 0 (0) | |

| Seizure | 10 (13.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Weakness and lethargy | 16 (22) | 0 (0) | |

| Speech disorder | 4 (5.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Vertigo | 6 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Restlessness | 9 (12.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Hallucination | 4 (5.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Agitation | 2 (2.7) | 0 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5 (6.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Abdominal pain and tenesmus | 6 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 6 (8.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Loss of consciousness | 3 (4.1) | 0 (0) b | |

| Dead c | - | 5 (6.8) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b These three patients with loss of consciousness died despite receiving adequate treatment.

c Five patients died during the first eight weeks despite receiving adequate treatment.

5. Discussion

Aluminum accumulation in patients with ESRD, particularly those undergoing chronic dialysis, is a well-documented clinical concern. It has been shown to lead to severe complications such as dialysis encephalopathy — a potentially fatal neurological disorder — as well as osteomalacia, marked by pathological bone fractures, and treatment-resistant anemia. The role of aluminum in these complications was initially suspected in the 1970s and firmly established by the late 1970s when a direct link between aluminum intoxication and both encephalopathy and osteomalacia was confirmed (12-18). Preventive measures, such as purification of dialysis water, have significantly reduced the incidence and severity of aluminum toxicity syndromes. Nevertheless, aluminum accumulation, particularly in the bones of dialysis patients, can also result from oral intake, even in the absence of overt clinical symptoms, remaining a significant concern for nephrologists. The introduction of DFO in 1980 as a chelating agent enabled effective removal of aluminum from the body, improving clinical outcomes (19, 20).

A 2015 study by Fulgenzi et al. investigated the association between aluminum toxicity and neurodegenerative diseases (21). In 2003, Sanadgol et al. (22) evaluated changes in serum aluminum levels before and after DFO testing and assessed the prevalence of aluminum toxicity among dialysis patients in Zahedan. This descriptive study included patients in the Dialysis Ward of Khatam Al-Anbiya Hospital in Zahedan with ESRD in 2002 who were undergoing regular dialysis. Blood samples were collected from all patients prior to dialysis to measure baseline aluminum levels. During the final hour of dialysis, DFO was infused intravenously at 5 mg/kg, diluted in 500 mL of glucose serum. Post-DFO, blood samples were collected before the next dialysis session to remeasure aluminum levels. The study found that serum aluminum levels increased significantly after DFO administration, with some patients exceeding 20 μg/L, and a maximum level of 90 μg/L, indicating a high prevalence of aluminum toxicity. These findings highlight the importance of regular plasma aluminum monitoring to prevent progressive symptoms of aluminum toxicity (22).

A 2010 study by Kan et al. compared low-dose DFO with standard-dose DFO for treating aluminum overload in hemodialysis patients. Participants with baseline serum aluminum ≥ 20 μg/L were randomly assigned to receive either 2.5 mg/kg/week (low-dose) or 5 mg/kg/week (standard-dose) DFO. No significant difference in therapeutic response was observed between the groups, suggesting that low-dose DFO may be as effective as standard-dose DFO (23).

In the present study, the most frequently observed neurological manifestation was tremor, affecting 21 patients (29%). Other symptoms included weakness and lethargy in 16 patients (22%), hallucinations in 4 patients (5.5%), and restlessness in 9 patients (12.3%). Elevated serum aluminum levels confirmed the diagnosis of aluminum toxicity. Patients were given the option to continue therapy via peritoneal dialysis. Therapeutic interventions — including increased frequency of peritoneal dialysis, targeted hemodialysis sessions, administration of DFO, or combinations of these strategies — resulted in significant symptomatic improvement. At baseline, 63% of patients exhibited clinical symptoms, which decreased to 6.8% following eight weeks of optimized therapy. Five patients succumbed during the treatment period. These findings highlight the critical need for systematic monitoring of serum aluminum levels and the timely initiation of appropriate interventions in dialysis patients. Study limitations include the relatively small cohort size and the observational study design, which may constrain the generalizability of these results to broader populations.

5.1. Conclusions

In patients with ESRD receiving dialysis who present with unusual neurological symptoms or hypotension, heavy metal or aluminum poisoning should be considered. Contamination of peritoneal dialysis solutions was confirmed in one batch due to raw material contamination during production. At baseline, 63% of patients were symptomatic; after eight weeks of appropriate therapy, 93.2% were asymptomatic. Early identification and chelation therapy with DFO significantly improve outcomes. Limitations of this study include the sample size and the single-center design, which should be considered when interpreting the results.