1. Background

Since the initial report of renal stone extraction via nephrostomy by Rupel and Brown in 1941, substantial progress has been achieved in both technique and equipment. The introduction of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) by Fernstrom and Johansson in 1976 marked a pivotal advancement, later enhanced by Alken et al. through the development of renal endoscopes and ultrasonic lithotripters. While extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) and flexible ureteroscopy are common modalities for treating nephrolithiasis, PCNL remains the preferred option in specific scenarios determined by stone size, location, morphology, and composition (1-3).

The PCNL is associated with complication rates ranging from 29% to 83%, including hemorrhage, renal system injury, infection, gastrointestinal tract perforation, vascular trauma, and pneumothorax (4). Among these, renal hemorrhage post-surgery is a particularly frequent and concerning complication, with perioperative bleeding reported in 7.5% to 23% of cases (5-7). Although most bleeding events can be managed conservatively, approximately 0.8% of patients require invasive hemostatic interventions (8). Consequently, surgeons must be prepared to identify and address both intraoperative and postoperative complications effectively.

Several studies have identified potential bleeding risk factors, such as diabetes, staghorn calculi, dilation method, and stone burden (5, 9). Additionally, variables like Body Mass Index (BMI), stone location, surgery duration, presence or absence of hydronephrosis, and the number of access tracts have also been implicated, though findings remain inconsistent (10, 11).

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to clarify the predictive variables associated with bleeding in patients undergoing PCNL at Imam Khomeini Hospital, affiliated with Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran, through a retrospective analysis.

3. Methods

This retrospective study analyzed 412 patients who underwent PCNL at Imam Khomeini Hospital in Ahvaz between January 2020 and January 2024. All procedures were conducted by a single experienced surgeon to ensure consistency. The average stone size was calculated by measuring the surface area of each patient’s renal calculi. All participants received prophylactic intravenous antibiotics 24 to 48 hours before surgery. A 5-French balloon catheter was positioned at the ureteropelvic junction to prevent the migration of stone fragments into the ureter during the procedure. Nephrostomy access was established using a guidewire, and lithotripsy was subsequently performed to fragment and remove the stones. The median intraoperative blood loss was determined to be 476.2 mL.

Patients were stratified into two groups:

- Group 1 (n = 206): Blood loss below the median

- Group 2 (n = 206): Blood loss above the median

Blood loss was estimated by evaluating postoperative hemoglobin decline, adjusted for any transfused blood volume. A stepwise multivariate regression model was used to explore associations between blood loss or transfusion requirements and several patient and procedural variables.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 16. A Student’s t-test was utilized to compare continuous variables such as stone size and BMI, while categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test. For multivariate analysis, logistic regression was applied. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

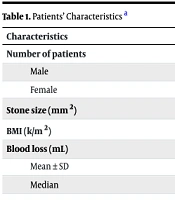

Out of the total 412 participants, 285 were male (69.17%) and 127 were female (30.83%), with an average age of 47.6 years (range, 26 - 77 years). The mean stone burden across all patients was 401.09 ± 198.13 mm2 (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 412 |

| Male | 285 (69.17) |

| Female | 127 (30.83) |

| Stone size (mm2) | 401.09 ± 198.13 |

| BMI (k/m2) | 25.32 ± 3.09 |

| Blood loss (mL) | |

| Mean ± SD | 505.87 ± 276 |

| Median | 476.2 |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD, unless otherwise indicated.

The average age in group 1 was 47.43 ± 18.72 years, while in group 2 it was 49.41 ± 19.21 years. This difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.36). Group 1 included 183 male and 23 female patients, whereas group 2 consisted of 178 male and 28 female patients. The mean estimated blood loss was 250.21 ± 161.32 mL in group 1 and 698.56 ± 203.19 mL in group 2. Additionally, BMI was significantly higher in group 2 (25.11 ± 2.48 kg/m2) compared to group 1 (22.32 ± 2.11 kg/m2), with a P-value of 0.02.

Stone size averaged 242.12 ± 197.34 mm2 in group 1 and 529.44 ± 211.56 mm2 in group 2, indicating a significantly larger stone burden in the latter group (P = 0.01). The frequency of stones located in the upper calyces was also significantly higher in group 2 (P = 0.03). When comparing stone multiplicity, group 1 had 113 patients with single stones and 93 with multiple stones. In contrast, group 2 had 65 patients with single stones and 141 with multiple stones. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.01), suggesting a greater bleeding risk with multiple calculi.

Surgical duration was considerably longer in group 2, averaging 134.75 ± 39.18 minutes, as opposed to 67.54 ± 21.94 minutes in group 1 (P = 0.01). Furthermore, the incidence of multiple nephrostomy accesses was significantly higher in group 2 (P = 0.01). Underlying medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, were more prevalent in group 2, with a statistically significant difference observed between the two groups. Additionally, patients with a prior history of PCNL were more frequently represented in group 2, also with a significant difference (Table 2).

| Variables | Group 1 | Group 2 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood loss (mL) | 250.21 ± 161.32 | 698.56 ± 203.19 | 0.00 |

| Sex | 0.87 | ||

| Male | 183 | 178 | |

| Female | 23 | 28 | |

| Age (y) | 47.43 ± 18.72 | 49.41 ± 19.21 | 0.36 |

| BMI | 22.32 ± 2.11 | 25.11 ± 2.48 | 0.02 |

| Stone position | |||

| Staghorn | 40 (19.4) | 35 (17.0) | 0.97 |

| Upper ureter | 65 (31.6) | 24 (11.7) | 0.89 |

| Renal pelvis | 43 (20.9) | 36 (17.5) | 0.93 |

| Calyceal | 31 (28.1) | 111 (53.9) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes | 6 (2.9) | 21 (10.2) | 0.02 |

| Stone size (mm²) | 242.12 ± 197.34 | 529.44 ± 211.56 | 0.01 |

| Number of stone | 0.01 | ||

| Single | 113 (54.9) | 65 (31.6) | |

| Multiple | 93 (45.1) | 141 (68.4) | |

| Multiple access tracts | 23 (11.16) | 65 (31.55) | 0.01 |

| Previous PCNL | 6 (2.9) | 17 (8.3) | 0.02 |

| Operative time (min) | 67.54 ± 21.94 | 134.75 ± 39.18 | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; PCNL, percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

5. Discussion

Our findings demonstrated a mean reduction in hemoglobin of 2.43 ± 1.57 g/dL following PCNL. Several variables showed a statistically significant association with increased intraoperative bleeding. These included elevated BMI, larger and multiple stones, upper calyceal location, use of multiple nephrostomy tracts, prolonged operative time, previous history of PCNL, and comorbid diabetes. The PCNL remains the standard treatment modality for renal stones larger than 20 mm, although recent miniaturized techniques have extended its application to smaller calculi as well. Despite its effectiveness, PCNL carries the risk of complications, with hemorrhage being one of the most critical. In our cohort, the transfusion rate was 3.5%, aligning with previously reported ranges of 3% to 23% (4, 12-17).

Diabetes mellitus, with a national prevalence of 18% in Malaysia (18), has been implicated in increased bleeding during PCNL. Akman et al. (9) previously reported a significant correlation between diabetes and transfusion requirements. However, subsequent studies have presented conflicting evidence (13, 19). In our study, diabetic patients exhibited greater hemoglobin deficits, supporting the association between this comorbidity and heightened bleeding risk.

In complex stone cases, multiple access tracts are often necessary for adequate stone clearance. However, creating several percutaneous entries may lead to renal parenchymal damage and vascular injury, thereby increasing the potential for hemorrhage. Our analysis corroborated findings from prior investigations identifying multiple access tracts as an independent risk factor for bleeding (8, 13, 20), although some studies have failed to show this association (14, 21). Furthermore, our results indicated that prolonged surgery duration and a history of prior PCNL procedures were linked to greater blood loss. These findings mirror those of Loo et al. (22), who highlighted stone characteristics — such as size, number, and anatomical position — as influential in predicting bleeding severity.

5.1. Conclusions

In summary, factors such as higher BMI, larger stone size, multiple stones, upper calyceal location, use of multiple nephrostomy tubes, extended operative duration, and the presence of diabetes mellitus significantly contributed to increased blood loss during PCNL. Recognizing these predictors can aid clinicians in risk stratification and perioperative planning to minimize hemorrhagic complications.