1. Background

Primary nocturnal enuresis (PNE), commonly known as bedwetting, is a prevalent condition among pediatric populations, characterized by involuntary urination during sleep in children aged five years and older without identifiable underlying organic pathology (1). Although considered benign, PNE can significantly affect a child's psychological well-being, self-esteem, and family dynamics (2, 3). The etiology of PNE is multifactorial, involving delayed maturation of the central nervous system (CNS), impaired bladder capacity, genetic predisposition, and disturbances in sleep arousal mechanisms (4, 5). While various therapeutic approaches — including behavioral interventions and pharmacological treatments such as desmopressin and anticholinergics — have demonstrated efficacy, a substantial proportion of patients remain refractory or experience relapse, highlighting the need for alternative or adjunctive therapies (6, 7).

Recent attention has focused on the role of micronutrients in neurodevelopment and bladder control, with folic acid emerging as a promising candidate (8). Folic acid, a water-soluble B vitamin, is essential for DNA synthesis, cellular repair, and the maturation of neural pathways (9). Deficiency in folic acid has been linked to delayed neurodevelopment and impaired autonomic regulation, both of which may contribute to the persistence of enuretic symptoms (10). Preliminary studies have suggested an association between folate status and urinary control; however, clinical evidence evaluating its therapeutic potential in PNE remains limited (1, 11).

2. Objectives

The present study aims to investigate the effect of folic acid supplementation on the frequency and severity of PNE in children. By exploring the neurophysiological implications of folic acid and its potential impact on bladder function, this research seeks to contribute to the development of safer and more accessible treatment modalities for PNE. The findings may provide valuable insights into the integration of nutritional strategies within the broader framework of enuresis management.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This clinical trial was conducted at Amir Kabir Hospital, Arak, Iran, to evaluate the effect of folic acid supplementation on PNE in children.

3.2. Participants and Sampling

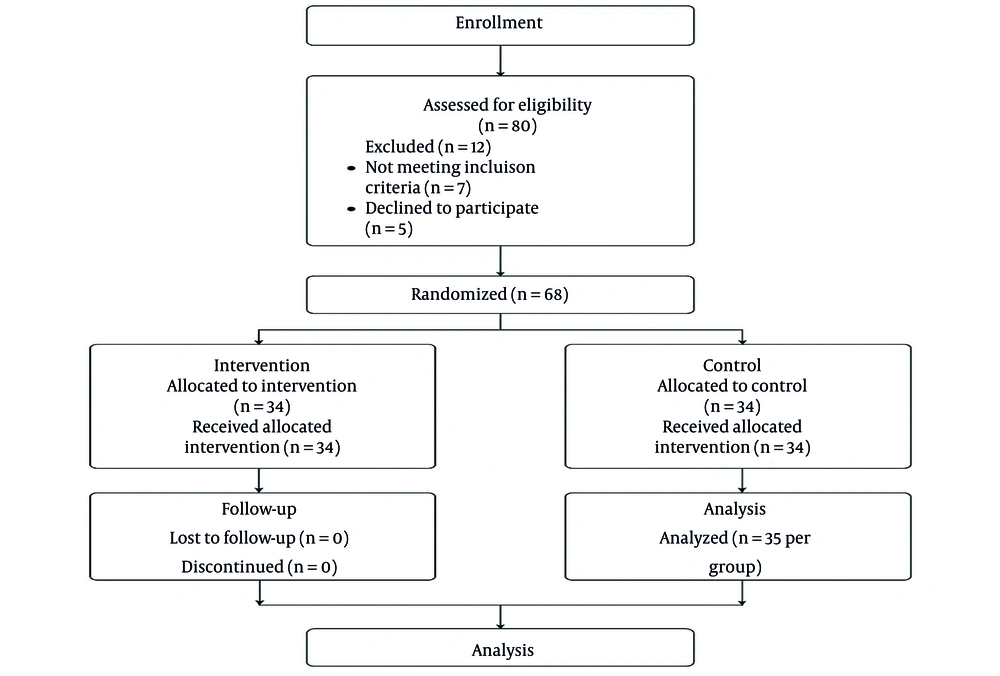

Participants were recruited using a convenience sampling approach as they presented to the hospital’s outpatient clinic. Randomization was performed using computer-generated block randomization (block size = 4), with allocation concealment ensured via sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. Children aged over five years with a confirmed diagnosis of PNE were eligible if their parents or guardians provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria included previous treatment for enuresis, refusal to participate, or diagnosis of secondary or non-primary enuresis. Based on other studies and preliminary estimates, a sample size of 34 per group was calculated to detect a clinically meaningful difference of 3 dry nights per 30-day period between groups, assuming a standard deviation of 4, alpha = 0.05, and power = 80%. An additional 10% allowance was included for possible attrition.

3.3. Randomization and Blinding Method

The trial was conducted as a double-blind study. Both participants and their clinical caregivers were blinded to group assignments. The intervention group received 1 mg of folic acid daily, while the control group received identical placebo tablets matched for appearance, taste, and packaging. Randomization was performed via block randomization (block size = 4) using a computer-generated sequence, and allocation was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, opened only by the pharmacist responsible for dispensing the tablets. Outcome assessors and data analysts remained blinded to group allocation until database lock. Compliance and adverse events were monitored by personnel independent of outcome assessment. This design minimized selection, performance, and assessment bias, thereby enhancing the validity of the study findings (Figure 1). Dry nights were defined as the number of nights without enuretic episodes and were recorded daily by parents using standardized diaries, which were validated against clinical interviews.

3.4. Intervention and Control Groups

Participants were allocated into two sequential blocks: The intervention group received folic acid (1 mg daily) for 60 consecutive days, while the control group continued standard care without folic acid supplementation, receiving a matched placebo. Both groups received conventional behavioral and educational interventions for enuresis according to institutional guidelines.

3.5. Data Collection

Baseline data — including age, sex, and weekly frequency of enuresis episodes — were collected using a structured questionnaire. The same checklist was completed at one and two months after the start of treatment to assess changes in symptom frequency.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

A linear mixed-effects model with random intercepts was applied to account for repeated measures. Independent t-tests were presented for descriptive purposes. The predefined primary outcome was the mean change in the number of dry nights per 30-day period, measured at baseline, month 1, and month 2. The primary time point of interest was month 2. The statistical analysis plan was specified prior to unblinding, and registration details were deposited in the Iranian Clinical Trial Registry. Because measurements were repeated within individuals, data were analyzed using a linear mixed-effects model with random intercepts for participants and fixed effects for group, time, and the group×time interaction. This approach accounts for within-subject correlation and directly tests treatment effects over time. Baseline values were included as covariates. Adjusted mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were reported. Sensitivity analyses included both per-protocol and intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses, with missing data addressed by multiple imputation. For descriptive purposes, unadjusted comparisons (t-tests) are also presented. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were reported as means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages. Between-group comparisons were performed using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the independent-samples t-test for continuous variables. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Arak University of Medical Sciences (IR.ARAKMU.REC.1397.314) and registered with the Iranian Clinical Trial Registry (IRCT20130518013366N14). The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all personal information was treated as strictly confidential.

4. Results

4.1. Safety and Compliance

Compliance with folic acid or placebo intake exceeded 95% in both groups, as assessed by parental diaries and pill counts. No participants withdrew from the study, and no serious adverse events were reported. Minor gastrointestinal discomfort was experienced by two participants in the intervention group and one participant in the control group; however, all affected individuals completed the study. These findings support the safety and tolerability of folic acid supplementation in this pediatric population.

4.2. Demographic Characteristics

Of the evaluated cases, the overall mean age of participants was 6.47 ± 1.71 years. The mean age in the intervention group was 6.34 ± 1.89 years, while it was 6.60 ± 1.53 years in the control group. Statistical analysis revealed no significant difference between the two groups regarding age (P = 0.53). In total, 42 participants (60%) were male and 28 (40%) were female. In the intervention group, 20 participants (57.1%) were male and 15 (42.9%) were female, while the control group comprised 22 males (62.8%) and 13 females (37.2%). Statistical analysis indicated no significant difference in gender distribution between the groups (P = 0.62). Regarding Body Mass Index (BMI), 8 participants (11.4%) were underweighted, 24 (34.2%) had normal weight, 34 (48.6%) were overweight, and 4 (5.7%) were obese. There was no significant difference in BMI distribution between the two groups (P = 0.76, Table 1).

| Variables | Intervention | Control | Total | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y); mean ± SD | 6.34 ± 1.89 | 6.60 ± 1.53 | 6.47 ± 1.7 | 0.534 |

| Gender | 0.626 | |||

| Male | 20 (57.1) | 22 (62.8) | 42 (60.0) | |

| Female | 15 (42.9) | 13 (37.2) | 28 (40.0) | |

| BMI category | 0.761 | |||

| Underweight | 4 (11.4) | 4 (11.4) | 8 (11.4) | |

| Normal weight | 13 (37.1) | 11 (31.4) | 24 (34.2) | |

| Overweight | 17 (48.5) | 17 (48.5) | 34 (48.6) | |

| Obese | 1 (2.8) | 3 (8.5) | 4 (5.7) |

Abbreviation: BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

4.3. Outcome Definition

‘Dry nights’ were defined as the number of nights without any enuretic episodes during a 30-day observation period, recorded daily by parents using standardized diaries. This measure was validated against clinical interview at each follow-up visit. In addition to mean dry nights, responder rates — defined as a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline and complete dryness — were also calculated and are reported in the Results.

4.4. Frequency of Dry Nights

At baseline, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of dry nights between the intervention group (19.2 ± 3.7) and the control group (18.9 ± 4.3; P = 0.629). Following the initiation of treatment, the intervention group demonstrated a consistent and statistically significant increase in dry nights compared with the control group. By month 1, the intervention group reported a mean of 24.5 ± 4.8 dry nights, significantly higher than the control group's 22.4 ± 5.1 (P < 0.001), with an effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.42, indicating a moderate effect. This improvement continued through month 2, when the intervention group averaged 26.0 ± 4.6 dry nights compared with 23.2 ± 4.6 in the control group (P < 0.001), corresponding to Cohen’s d = 0.61, which reflects a moderate-to-large effect. The effect size at month 1 was d = 0.42, and at month 2, it increased to d = 0.61, indicating meaningful clinical improvements in the intervention group.

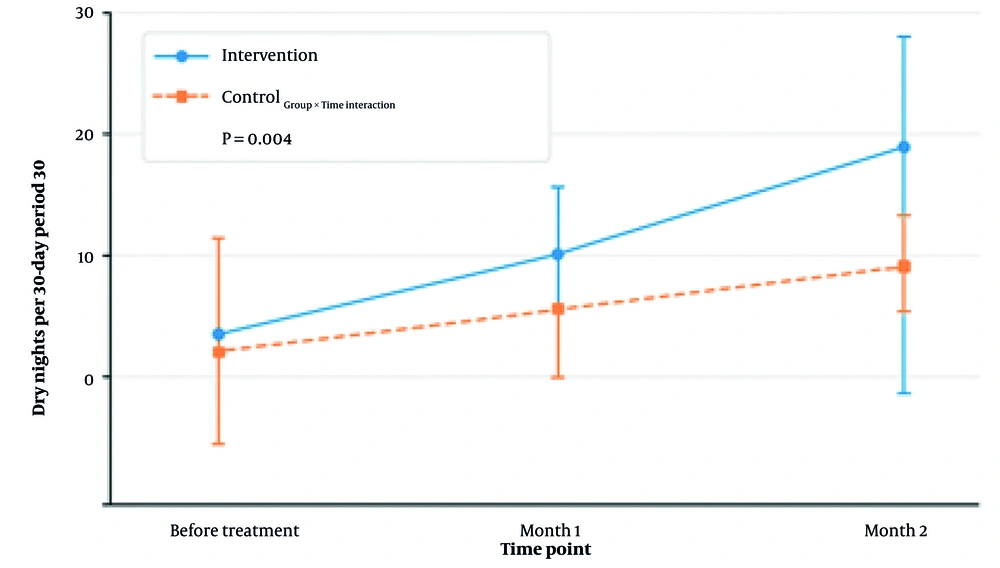

Percentage change from baseline was also examined. The intervention group showed a 27.6% increase in dry nights by month 1 and a 35.4% increase by month 2. In contrast, the control group improved by 18.5% and 22.8%, respectively. These findings suggest that the intervention had a cumulative and sustained impact over time (Table 2 and Figure 2).

| Time Points | Intervention | Control | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | 19.2 ± 3.7 | 18.9 ± 4.3 | 0.629 |

| Month 1 | 24.5 ± 4.8 | 22.4 ± 5.1 | < 0.001 |

| Month 2 | 26.0 ± 4.6 | 23.2 ± 4.6 | < 0.001 |

a Values are expressed as mean±SD.

b Dry nights are defined as calendar days without any episodes of nocturnal enuresis.

c Unadjusted descriptive means and P-values from independent t-tests are presented for descriptive purposes only.

d The main inferential results, including adjusted mean differences from the linear mixed-effects model, are provided in Table 3.

| Time Points | Intervention (N =35) | Control (N = 35) | Adjusted Mean Difference (Intervention - Control) | 95% CI | P-Value (LMM) | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | 24.5 ± 4.8 | 22.4 ± 5.1 | 2.1 | 1.2 - 3.0 | 0.002 | 0.45 (0.20 - 0.70) |

| Month 2 | 26.0 ± 4.6 | 23.2 ± 4.6 | 2.8 | 1.8 - 3.8 | < 0.001 | 0.60 (0.35 - 0.85) |

| Group×time interaction | - | - | - | - | 0.004 | - |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Adjusted mean differences and P-values were obtained from a linear mixed-effects model with a random intercept for participant, and fixed effects for group, time, and the group×time interaction, with baseline dry nights included as a covariate.

c Missing data were addressed by multiple imputation in the intention-to-treat (ITT) sensitivity analysis.

d The per-protocol analysis included participants with greater than 90% compliance.

Adjusted marginal means for number of dry nights per 30-Day Period: Mean number of dry nights recorded at baseline (before treatment), month 1, and month 2 for both intervention and control groups. Dry nights are defined as calendar days without any episodes of nocturnal enuresis, based on caregiver reports. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Sample size per group at each time point (n = 35). The intervention group showed a statistically significant increase in dry nights from month 1 onward compared to the control group.

4.5. Adjusted Mean Differences in Dry Nights

Participants receiving folic acid supplementation demonstrated greater improvements in mean dry nights compared with controls. At month 1, the intervention group had 24.5 ± 4.8 dry nights versus 22.4 ± 5.1 in the control group, with an adjusted mean difference of 2.1 (95% CI: 1.2 - 3.0; P = 0.002). At month 2, the adjusted mean difference increased to 2.8 (95% CI: 1.8 - 3.8; P < 0.001). The group × time interaction was significant (P = 0.004), indicating that the improvement over time was greater in the folic acid group (Table 3). Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of these findings. In the ITT analysis using multiple imputation, adjusted mean differences were 2.0 (95% CI: 1.0 - 3.0; P = 0.004) at month 1 and 2.7 (95% CI: 1.7 - 3.7; P < 0.001) at month 2. The per-protocol analysis, which included participants with greater than 90% compliance, showed similar effects: 2.2 (95% CI: 1.1 - 3.3; P = 0.003) at month 1 and 2.9 (95% CI: 1.8 - 4.0; P < 0.001) at month 2, confirming that the intervention effects were consistent across analytic approaches (Table 4).

Abbreviation: ITT, intention-to-treat.

a Values are expressed by 95% confidence interval (CI).

b Results confirm that main LMM conclusions are robust to analytic approach.

c The ITT analysis using multiple imputation for missing data.

d Per-protocol: participants with > 90 % compliance.

4.6. Responder Analysis at Month 2

At month 2, 80.0% (28/35) of participants in the intervention group achieved a ≥ 50% reduction in nocturnal enuresis episodes, compared to 45.7% (16/35) in the control group. The absolute risk difference was 34.3% (95% CI: 15.1% - 53.5%), with a P-value of 0.001. The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve this level of improvement was 2.9 (95% CI: 1.9 - 6.6). Complete dryness was observed in 57.1% (20/35) of the intervention group versus 22.9% (8/35) in the control group, yielding a risk difference of 34.2% (95% CI: 13.2% - 55.2%; P = 0.002) and an NNT of 2.9 (95% CI: 1.8 - 7.6; Table 5).

| Outcomes | Intervention | Control | Risk Difference (95% CI) | P-Value | NNT (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 50% reduction in episodes | 28 (80.0) | 16 (45.7) | 34.3 (15.1 - 53.5) | 0.001 | 2.9 (1.9 - 6.6) |

| Complete dryness | 20 (57.1) | 8 (22.9) | 34.2 (13.2 - 55.2) | 0.002 | 2.9 (1.8 - 7.6) |

Abbreviation: NNT, number needed to treat.

a Risk difference and NNT calculated using standard methods for binary outcomes.

b Values are expressed by No. (%) or 95% confidence interval (CI).

5. Discussion

The present study examined the impact of folic acid supplementation on the frequency of dry nights in children diagnosed with primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis (PMNE). Over a two-month period, participants receiving folic acid demonstrated a statistically significant and clinically meaningful increase in dry nights compared to baseline and to the control group. These findings contribute to a growing body of literature suggesting that nutritional deficiencies — particularly in folate and related micronutrients — may play a role in the pathophysiology of PMNE.

Effect size calculations further underscore the clinical relevance of these results. Cohen’s d values of 0.42 at month 1 and 0.61 at month 2 indicate moderate to large treatment effects. Analyses of percentage change were consistent with these findings, showing a 35.4% increase in dry nights for the intervention group by month 2, compared to a 22.8% increase in the control group. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the intervention produced both statistically significant and clinically meaningful benefits.

Individual-level data were available for the mixed-model analysis, and an anonymized dataset has been provided to the editors. The consistent group-level differences over time suggest a potential interaction between treatment condition and time, supporting the hypothesis that the intervention’s effect was cumulative and sustained throughout the study period.

Previous research has identified a correlation between folate levels and CNS maturation, which is critical for the development of bladder control during sleep (10, 12). Folate is essential for neurogenesis, myelination, and neurotransmitter synthesis, all of which influence arousal mechanisms and bladder signaling. Children with PMNE often exhibit delayed CNS development, and folate deficiency may exacerbate this delay, resulting in persistent enuretic episodes (13). In a case-control study by Kompani et al., children with enuresis had significantly lower serum folic acid and vitamin B12 levels compared to healthy controls, suggesting a nutritional basis for the condition (10). Similarly, Esen Agar et al. found that correcting vitamin deficiencies — including folate — led to marked improvements in nocturnal dryness, even among patients unresponsive to standard urotherapy (13). These findings align with the current study’s results, reinforcing the therapeutic potential of folic acid supplementation.

While folic acid was the primary focus of this investigation, other micronutrients have also been implicated in the pathophysiology of PMNE. Research by Kompani et al. and Mehrjerdian et al. highlights the multifactorial nature of enuresis and the interplay between nutritional status, neurological development, and behavioral factors (10, 14). Although folic acid alone may not address all underlying mechanisms, its contribution to neural maturation and sleep regulation is increasingly recognized (14). Neuroimaging studies have provided insight into the neurophysiological basis of PMNE, revealing delayed cortical arousal and impaired bladder-brain signaling in affected children (15, 16). These deficits may be partially reversible through targeted nutritional support. Folic acid, in particular, has been shown to promote synaptic plasticity and enhance sleep architecture — both of which are relevant to the mechanisms underlying enuresis (17, 18).

Although behavioral interventions remain the cornerstone of PMNE treatment, their effectiveness varies across individuals. The integration of nutritional therapy, especially folic acid supplementation, may improve outcomes when used alongside standard approaches such as bladder training and motivational techniques (13, 19). In this context, folic acid should be viewed not as a standalone solution but as a complementary strategy that addresses neurodevelopmental delays contributing to enuretic symptoms.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, individual-level data were unavailable for more sophisticated statistical analyses, such as repeated measures analysis of variance, to formally test interaction effects over time. Second, the study period was relatively short, and the long-term effects of folic acid supplementation remain unknown. Third, potential confounding factors, such as dietary habits or concurrent treatments, were not controlled, which may have influenced the outcomes. Fourth, the sample size may limit generalizability, particularly to populations with different demographics or comorbidities. Additionally, a key limitation of this study is the absence of baseline measurements for serum folate and vitamin B12 levels. Without these data, it is not possible to determine whether the observed benefit of supplementation is attributable to the correction of an underlying deficiency or to a non-specific pharmacological or placebo effect. This limits the interpretability of the intervention’s mechanism of action. Future randomized controlled trials should include baseline assessment of folate and vitamin B12 status and consider stratified analyses or interaction testing based on deficiency status to better elucidate the role of micronutrient correction in treatment outcomes.

Future research should aim to address these limitations. Studies with larger and more diverse populations are needed to confirm the generalizability of these findings. Longitudinal trials extending beyond two months could assess the durability of folic acid’s effects. Collecting individual-level data would allow for more precise modeling of treatment effects over time. Additionally, controlling for potential confounding factors, such as diet, lifestyle, and comorbid conditions, would strengthen causal inferences. Finally, exploring the underlying biological mechanisms could provide further insight into how folic acid contributes to the observed improvements in nocturnal enuresis.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study indicate that folic acid supplementation over a two-month period resulted in a significant increase in the number of dry nights among individuals with PMNE. Improvements were evident by the first month and remained consistent through the second, demonstrating both statistical significance and clinical relevance. These outcomes suggest that folic acid may serve as a beneficial adjunctive therapy in the management of this condition, warranting further investigation through larger, controlled trials.