1. Background

Diabetes is the most common systemic metabolic disorder worldwide, characterized by elevated blood glucose levels resulting from varying degrees of insulin resistance or impaired insulin secretion (1). Poor blood sugar and weight control are among the most prevalent and significant challenges for patients with type 2 diabetes (2). Diabetes is a chronic disease affecting more than 400 million people and causing millions of deaths annually. The World Health Organization predicts that by 2030, diabetes will become the seventh leading cause of death (3). According to Infant (4), the global prevalence of diabetes is increasing, with an estimated 31.1 billion individuals expected to be affected by 2050. The disease is associated with serious complications, comorbidities, and increased mortality. Global and regional trends indicate that approximately 462 million people were affected by diabetes worldwide in 2017, with projections of more than 707 million by 2030 (5-7). The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing rapidly compared to type 1 diabetes (1). In Iran, statistics from 2021 indicated that 5,450 individuals were diagnosed with diabetes, with projections estimating 9,545 cases by 2045 (8).

The significance of diabetes lies in its high prevalence and numerous complications. Diabetes often leads to physical and psychological complications, including disability, premature death, social relationship difficulties, and cardiovascular, ocular, and renal issues (9). Uncontrolled diabetes may result in complications such as retinopathy, nephropathy, diabetic ketoacidosis, recurrent infections, cardiovascular diseases, and a reduction in life expectancy by 10 years (10). Managing blood sugar levels is essential to prevent both acute and long-term complications (11, 12). Monitoring health indicators such as hemoglobin A1c (HbA1C), fasting, and non-fasting blood glucose is crucial for identifying individuals with diabetes and assessing disease control (13, 14). The fasting blood glucose test is commonly used to screen diabetic patients and reflects glycemic control over the previous two to three months (15). The HbA1C is a reliable indicator for quarterly blood sugar control (16), reflecting the individual's glucose status over the preceding two to three months (17), with values greater than 5.6% indicative of diabetes. Fasting blood glucose above 126 mg/dL and two-hour postprandial blood glucose (2hpp) above 200 mg/dL are diagnostic markers for diabetes (18). The HbA1C test is the gold standard for long-term monitoring; while fasting blood glucose serves as a short-term indicator (14).

Various theoretical perspectives have been proposed for disease prevention and control. In recent decades, alongside medication, behavioral and psychological interventions have been introduced for diabetic patients to reduce cognitive and other associated issues (19, 20). Studies suggest that psychological interventions are more effective than standard medical care in reducing blood sugar levels and HbA1C (21-23). The chronic nature of diabetes, its irreversible complications, required lifestyle and dietary changes, frequent testing, fear of severe outcomes, and reduced quality of life, underscore the need for psychological treatments (24).

Reality therapy is one psychological approach that has received attention in this context. Its effectiveness for type 2 diabetes has been confirmed. This therapeutic method emphasizes confronting reality, accepting personal responsibility, and making moral judgments about behavior, thereby fostering a successful identity (25). Individuals are held responsible for their actions, thoughts, and feelings, and are not considered victims of their circumstances unless they choose to be (26).

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is another approach influencing diabetes treatment. It is derived from cognitive-behavioral therapy and focuses on behavioral changes (27). The DBT comprises four main components: Mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness (28, 29). Mastery of these skills leads to improved emotional self-regulation and control over distressing emotions.

Numerous studies highlight the effectiveness of psychological therapies for chronic patients (30-34). Given the prevalence of diabetes, the importance of education in its management, and the impact of reality therapy and DBT, there is a lack of comparative research on their effects on fasting blood sugar (FBS), 2hpp, and HbA1C levels. Thus, it is essential to determine the comparative effectiveness of these approaches in women with diabetes.

2. Objectives

Given this research gap, the primary question is whether group reality therapy and group DBT are effective in reducing FBS, 2hpp, and HbA1C levels in women with type 2 diabetes.

3. Methods

This study employed a semi-experimental design with pre-test, post-test, and two-month follow-up and included a control group. The statistical population comprised all women with type 2 diabetes attending a specialized diabetes clinic in Shiraz in May 2024.

Sample size determination was based on the primary outcome (FBS) and previous studies. Assuming a clinically meaningful difference of 15 mg/dL, a standard deviation (SD) of 18 mg/dL, a two-tailed significance level of 0.05, and a statistical power of 80%, the required sample size was approximately 23 participants per group. However, due to recruitment constraints, 15 participants were included in each group (total n = 45), with an achieved power of approximately 63%. Participants were selected using purposive and convenience sampling. Random allocation to the three groups was generated by computer software, with allocation concealment maintained by an independent researcher.

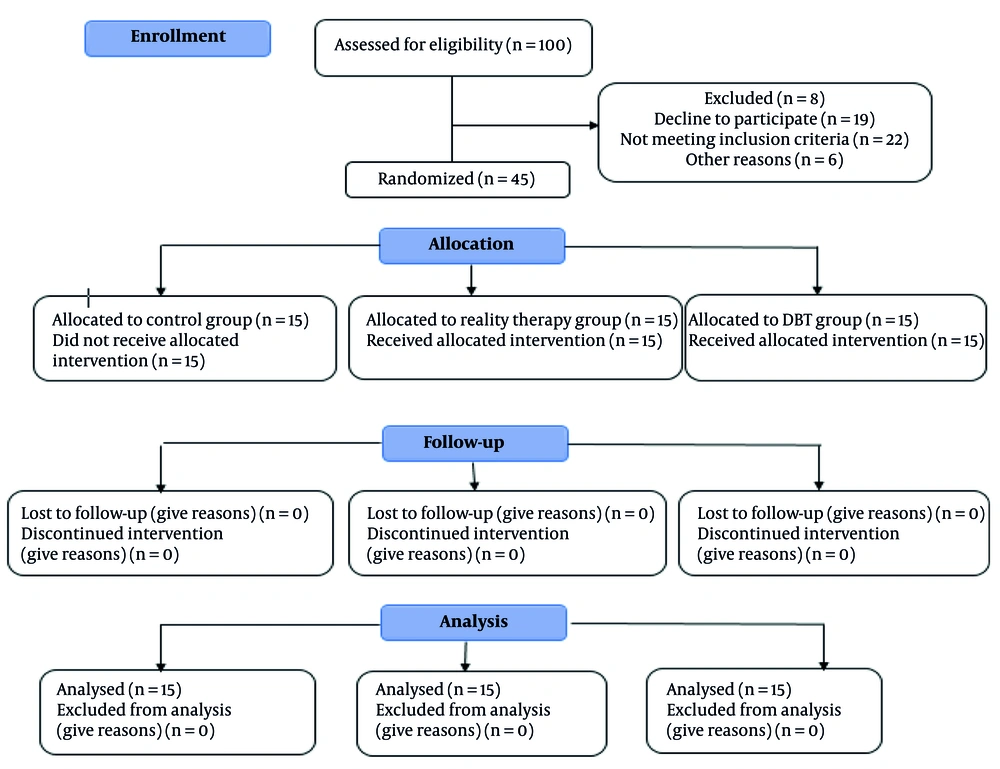

A summary of the content of DBT and reality therapy training is provided in Table 1. The CONSORT diagram for the study is shown in Figure 1.

| Sessions | Content of DBT | Content of Reality Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| First | Introducing and familiarizing members, establishing appropriate communication with group members, determining the structure of meetings, stating rules and regulations, outlining goals and introducing the training course, obtaining commitments, and conducting questionnaires for pre-testing | Introduction and familiarization of members, establishing appropriate communication with group members, determining the structure of sessions, stating rules and regulations, outlining goals and introducing the training course, obtaining commitment, and conducting a pre-test |

| Second and third | Training in mindfulness skills; familiarization, analytical mind - skills of 'what is' mindfulness; skills of 'how to' mindfulness; assigning homework for the next session | Introduction to Choice Theory and Reality Therapy, introduction to the reasons and how behaviors occur, introduction to the five basic needs of humans and helping members to recognize their own needs, definition of the desired world, and providing assignments for the next session |

| Fourth and fifth | Review of the assignments from the previous session, training in distress tolerance skills (attention shifting, self-soothing, moment enhancement, acceptance of reality; desire, mindfulness towards thoughts), lifestyle training; assigning homework for the next session | Review of the assignments from the previous session, assessing individuals' perceptions and interpretations of their illness and its complications and consequences, introducing type 2 diabetes in simple language; what do you want? Introducing overall behavior and its components, the behavior machine metaphor, introducing the four types of conflicts - assigning homework for the next session |

| Sixth and seventh | Review of the assignments from the previous session, training in emotion regulation skills (understanding emotions; recognizing and naming emotions; increasing positive emotions), introducing type 2 diabetes in simple language, assigning homework for the next session | Review of the assignments from the previous session; conducting a meditation exercise to demonstrate the effectiveness of changing actions and thoughts on feelings and physiology; introducing seven destructive behaviors in human relationships; introducing seven constructive behaviors in relationships; reviewing past successes; the role of negative self-talk; assigning homework for the next session |

| Eighth and ninth | Review of the assignments from the previous session, training in emotion regulation skills (mindfulness towards emotions; opposite action; problem-solving), assigning homework for the next session | Review of the assignments from the previous session; introduction to internal control; training on the ten principles of choice theory - neuroplasticity and changing our beliefs about change; developing a concrete plan to avoid external control and submission to it - introduction; goal setting; assigning homework for the next session |

| Tenth and eleventh | Review of the assignments from the previous session, training in interpersonal effectiveness skills (understanding barriers, clarifying goals; technique until completion; puzzle technique, equation; evaluating options), assigning homework for the next session | Review of the assignments from the previous session, training on self-assessment, discussion about the alignment of values and behavior; training on the 5 levels of commitment; evaluating a plan and the characteristics of an effective plan - implementing the plan and examining its drawbacks; assigning homework for the next session. |

| Twelfth | Review of the assignments from the previous session, discussion about the consequences of applying the techniques, receiving feedback from group members, conducting a post-test, providing necessary explanations about the follow-up program; thanking and appreciating the participants and giving gifts to the participants; concluding the therapy sessions | Review of the assignments from the previous session; discussion about the goals and the extent to which group members have achieved them; overall review of all the concepts of the course; answering questions; conducting a post-test; providing necessary explanations about the follow-up program; thanking and appreciating the participants and giving gifts to the participants; concluding the therapy sessions |

Abbreviation: DBT, dialectical behavior therapy.

Inclusion criteria were female gender, age 40 to 60 years, at least one year since diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (per medical records), willingness to participate, informed consent, minimum literacy, no concurrent or recent psychological services, absence of severe neurological disorders (as diagnosed by a physician), and physical ability to participate. Exclusion criteria were more than two absences from sessions and lack of willingness to continue.

1.3. Data Collection Tools

FBS, 2hpp, and HbA1C tests were used. The FBS was measured using 5 cc of venous blood after 12 to 14 hours of fasting. The two-hour postprandial glucose test was conducted similarly. The HbA1C was assessed using standard procedures. Blood samples were collected, preserved, and coded appropriately.

After coordinating with the diabetes clinic, all three groups underwent baseline testing. The DBT group received 12 weekly sessions (90 minutes each) based on Marsha Linehan's protocol (2015). The reality therapy group received 12 weekly sessions (90 minutes each) based on Stutey and Wubbolding's protocol (35). The control group received no intervention. After the sessions, all groups repeated the tests. Two months post-intervention, all groups underwent the tests again. At the end of the study, the control group was offered positive psychotherapy if desired. The content session of the DBT and reality therapy is summarized in Table 1.

All ethical considerations, including confidentiality and voluntary participation, were observed. The study was approved by the Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch (ethics code: IR.IAU.K.REC.1402.145). Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software version 21 and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).

4. Results

According to Table 2., the demographic information of the participants in the study is presented. The distribution of participants in the experimental and control groups regarding demographic variables is almost the same. The mean ± SD age of the reality therapy experimental group was 46.54 ± 55.5, for the DBT experimental group it was 26.57 ± 37.2, and for the control group, it was 20.53 ± 86.5.

| Variables and Execution Order | DBT (N = 15) | Reality Therapy (N = 15) | Control Group (N = 15) | Chi-square | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 2.64 | 0.619 | |||

| High school diploma and above | 4 (27) | 6 ± 40 | 6 ± 40 | ||

| Diploma and post-graduate diploma | 9 (60) | 7 ± 47 | 5 ± 33 | ||

| Bachelor's degree and above | 2 (13) | 2 ± 13 | 4 ± 27 | ||

| Occupation | 2.30 | 0.663 | |||

| Housewife | 13 (88) | 12 ± 80 | 10 ± 67 | ||

| Employee | 1 (6) | 1 ± 6 | 3 ± 20 | ||

| Retired | 1 (6) | 2 ± 14 | 2 ± 13 | ||

| Married | 0.257 | 0.879 | |||

| Married | 12 (80) | 11 ± 73 | 12 ± 80 | ||

| Single (divorced, widowed) | 3 (20) | 4 ± 27 | 3 ± 20 | ||

| Age | |||||

| Mean | 57.266 | 54.46 | 53.20 | F | P |

| Single (divorced, widowed) | 2.37 | 5.55 | 5.85 | 2.75 | 0.075 |

Abbreviation: DBT, dialectical behavior therapy.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Demographic characteristics were comparable across groups, with similar distributions regarding education, employment, and marital status. The mean ± SD ages were 46.54 ± 55.5 in the reality therapy group, 57.26 ± 37.2 in the DBT group, and 53.20 ± 86.5 in the control group. The three groups were similar in education (χ2 = 2.64, P = 0.619), employment (χ2 = 2.30, P = 0.663), and marital status (χ2 = 2.57, P = 0.879). The mean ages were also not significantly different (F = 2.75, P = 0.075), indicating balanced groups at baseline. Descriptive indices, means, SDs, and results of the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality are reported in Table 2.

Repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant reductions in FBS, 2hpp, and HbA1C in both DBT and reality therapy groups over time (P < 0.001). The control group showed no significant changes. Between-group ANOVA indicated significant differences, with effect sizes (η2) ranging from 0.494 to 0.602, representing medium to large effects.

Repeated measures ANOVA was performed to assess within-group changes across pretest, posttest, and follow-up for FBS, two-hour postprandial glucose (2hpp), and HbA1C. As shown in Table 3, both DBT and reality therapy significantly reduced all outcomes over time (P < 0.001), while the control group showed no significant changes. Between-group ANOVA indicated significant differences among the three groups, with effect sizes (η2) ranging from 0.494 to 0.602, demonstrating medium to large intervention effects.

| Variables | Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up | Within-Group P (RM-ANOVA) b | Between-Group F c | Effect Size (η2) c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBS (mg/dL) | 20.53 | 0.494 | ||||

| DBT | 140.06 ± 15.72 | 117.06 ± 14.39 | 120.93 ± 18.07 | < 0.001 d | ||

| Reality therapy | 134.26 ± 23.33 | 116.33 ± 23.66 | 119.93 ± 21.53 | < 0.001 d | ||

| Control | 135.33 ± 18.65 | 145.60 ± 16.41 | 150.26 ± 19.37 | 0.091 | ||

| 2hpp (mg/dL) | 21.13 | 0.502 | ||||

| DBT | 155.53 ± 23.28 | 131.00 ± 21.25 | 131.13 ± 18.41 | < 0.001 d | ||

| Reality therapy | 145.26 ± 22.18 | 112.40 ± 23.38 | 114.80 ± 23.71 | < 0.001 d | ||

| Control | 155.80 ± 17.63 | 155.33 ± 15.40 | 155.46 ± 16.03 | 0.872 | ||

| HbA1C (%) | 31.74 | 0.602 | ||||

| DBT | 7.00 ± 0.55 | 6.23 ± 0.61 | 6.34 ± 0.69 | < 0.001 d | ||

| Reality therapy | 6.90 ± 0.77 | 6.42 ± 0.70 | 6.35 ± 0.74 | < 0.001 d | ||

| Control | 7.18 ± 0.55 | 7.20 ± 0.53 | 7.24 ± 0.52 | 0.281 |

Abbreviations: RM-ANOVA, repeated measures analysis of variance; FBS, fasting blood sugar; DBT, dialectical behavior therapy; 2hpp, two-hour postprandial glucose; HbA1C, hemoglobin A1c.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b Within-group P-values were obtained using repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA).

c Between-group F and effect sizes (η2) were calculated for the overall comparison among the three groups.

d Values in bold indicate statistically significant differences within each group across time points (P < 0.05).

Considering the significance of the interaction between the research groups and measurement occasions in the two-way ANOVA with repeated measures for the FBS variable (F = 20.53, P < 0.01), the 2hpp variable (F = 21.12, P < 0.01), and the HbA1C variable (F = 31.73, P < 0.01), which indicates a significant difference among the nine means compared in each analysis, further investigation into the effectiveness of the two treatments in the study and their comparison was conducted.

The mean differences between the pre-test and post-test scores in the three research groups were compared using the Bonferroni post hoc test, and the results can be seen in Table 4.

| Variables | Mean Differential Scores | Dialectical Behavioral Therapy | Reality Therapy | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBS | ||||

| Dialectical behavioral therapy | 00.23 | - | 51.2 | 71.17 a |

| Reality therapy | 93.17 | -51.2 | - | 22.2 a |

| Control | -26.1 | 71.17 | 22.2 a | - |

| 2hpp | ||||

| Dialectical behavioral therapy | 53.24 | - | 06.15 | -31.16 a |

| Reality therapy | 86.32 | -06.15 | - | -37.31 a |

| Control | 0.467 | 31.116 a | -37.31 a | - |

| A1C | ||||

| Dialectical behavioral therapy | 0.767 | - | -0.071 | 0.722 a |

| Reality therapy | 0.473 | 0.071 | - | 0.651 a |

| Control | -0.027 | 0.722 a | 0.651 a | - |

Abbreviations: FBS, fasting blood sugar; 2hpp, two-hour postprandial glucose.

a P < 0.01.

In Table 4, it can be observed that the effectiveness of DBT and reality therapy (RT) on the FBS, 2hpp, and HbA1C variables is significant (P < 0.01). However, the comparison of the effects of the two intervention approaches on the dependent variables indicates that the difference between the DBT group and the reality therapy group is not significant (P > 0.05). Therefore, the results of the mean difference between the two treatment groups showed that the scores of the variable FBS, 2hpp, and HbA1C in the experimental groups were lower in the post-test stage than in the pre-test stage compared to the control group (P < 0.001). Also, this variable had a significant difference with the pre-test stage in the follow-up stage (P < 0.001). However, no significant difference was observed between the two post-test and follow-up stages. The results also showed that the reality therapy experimental group had a greater effect on reducing blood sugar (in three variables: FBS, two-hour blood sugar, and HbA1C) in diabetic patients than the DBT experimental group, but this difference was not statistically significant. Finally, to assess the sustainability of the effectiveness of the interventions, a paired samples t-test was conducted for the post-test and follow-up data, separated by the two experimental groups. The results for the DBT group were as follows: For FBS (t = -1.236, P = 0.237), 2hpp (t = -0.110, P = 0.914), and for HbA1C (t = 0.129, P = 0.894).

5. Discussion

This study examined the effects of reality therapy and DBT on FBS, 2hpp, and HbA1C in women with type 2 diabetes. The findings revealed significant reductions in all three variables in the experimental groups, sustained for two months post-intervention, with no significant difference between the two therapies at either post-test or follow-up.

While there is limited research directly comparing these interventions for glycemic control in women with type 2 diabetes, the present results align with prior studies demonstrating the effectiveness of psychological interventions in diabetes management. For instance, Sbroma Tomaro et al. (30) reported that psychological interventions reduced the need for hypoglycemic treatment and slowed progression to diabetes. Watanabe et al. (31) found that lifestyle modification significantly aided diabetes control. Shahnavazi et al. (32) and Nasir Dehghan et al. (33) supported the role of reality therapy in improving lifestyle and self-care, while Sheikh et al. (34) demonstrated the effectiveness of DBT in reducing depression and FBS.

Both interventions are classified as third-wave cognitive-behavioral therapies, emphasizing behavioral change, self-awareness, and responsibility. Their shared mechanisms likely account for their similar effectiveness in reducing blood sugar.

Reality therapy teaches individuals to control their lives by making different choices, thereby altering feelings and physiological states. Group interaction and the sharing of experiences further enhance this process (35, 36). Reality therapy may reduce blood sugar by promoting healthier lifestyle choices and emotional regulation, which are critical for diabetes management (37).

The DBT, by fostering communication skills, self-awareness, problem-solving, and distress tolerance, enhances psychological resilience and disease management (38, 39). Its focus on mindfulness and emotional regulation equips patients to confront emotions and reduce maladaptive behaviors, contributing to improved glycemic control (40, 41).

A limitation of this study is its restriction to women with type 2 diabetes. It is recommended that future health policies consider incorporating psychological therapies such as reality therapy and DBT for chronic disease management.

5.1. Conclusions

Given the significant effect of both DBT and reality therapy in reducing blood sugar levels in women with type 2 diabetes, it is recommended that these interventions be implemented in diabetes treatment centers to improve patient outcomes. The findings suggest that these methods are effective, accessible, and feasible options for diabetes management in women and may enhance self-care and treatment adherence. Implementation of such therapies can bridge the gap between clinical and real-life environments, facilitating better disease management and quality of life. The results have both theoretical and practical implications for psychologists, psychiatrists, and healthcare policymakers.