1. Context

Commercially pure titanium (CP-Ti) is the preferred material for dental implants due to its biocompatibility and mechanical properties, forming a thin oxide layer (10 - 100 Å) that promotes osseointegration. Osseointegration, as defined by Branemark, is a “direct structural and functional connection between living bone and the implant surface under functional load” (1-4). Clinical studies on dental implants in humans show favorable long-term survival rates, though outcomes depend on patient and clinical factors. Previous studies reported a 5-year survival rate of 90% - 95% for implant-supported prostheses in humans, with a failure rate of approximately 5% - 10% due to complications such as peri-implantitis, mechanical failures (e.g., screw loosening or fracture), and inadequate osseointegration (5, 6). Similarly, Jain et al. found a survival rate of 83.5% - 87.2% for dental implants in humans over 5 - 6 years, with failures associated with risk factors such as smoking, poor bone quality, and systemic conditions like diabetes (7). Additionally, Sinsareekul et al. compared endodontically treated teeth to implant-supported prostheses, reporting a cumulative survival rate of 88.7% - 93.2% for implants over 5 - 7 years in human clinical settings, noting peri-implantitis and occlusal overload as significant contributors to implant failure (8). Ganapathy et al. further noted that immediate implants in periodontally compromised patients achieved a survival rate of 85% - 90% over 5 years, with higher failure rates in cases of severe periodontal bone loss (9). Upon contact with body fluids, proteins such as fibronectin adsorb onto the implant surface, triggering biological responses essential for wound healing and osseointegration (8, 10, 11). Fibronectin, a glycoprotein with soluble (plasma) and insoluble [extracellular matrix (ECM)] forms (440 - 500 kDa), enhances cell adhesion and migration by binding to integrins via the Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser sequence, thereby promoting osteoblast differentiation and bone formation (12-16). Coating CP-Ti implants with fibronectin or combining it with materials such as beta-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) or BMP-7 can enhance implant surface bioactivity, creating biomimetic surfaces that replicate the natural ECM (17-19).

2. Objectives

Despite these advancements, variability in fibronectin’s efficacy across animal models and limited clinical data in humans highlight the need for further research. This systematic review addresses the research question: Does fibronectin enhance bone regeneration? By evaluating its effects on osseointegration and bone healing in animal studies, this review aims to clarify fibronectin’s potential and identify gaps for future clinical research.

3. Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to address the research question: Does fibronectin alter bone regeneration?

3.1. Eligibility Criteria

The criteria for inclusion of studies in this review (PICOS) were as follows:

1. Population (P): Dental implants

2. Intervention (I): Fibronectin

3. Comparison (C): Calcium phosphate, β-TCP, Uncoated or No coating

4. Outcome (O): Bone Regeneration, Osseointegration

5. Study design (S): Animal study

6. Exclusion: The following studies were excluded: Not related to the topic, clinical studies, review studies, case reports, congress abstracts, personal opinions, books and/or book chapters, and theses.

3.2. Information Sources, Search Strategy, and Study Selection

Two investigators independently conducted searches in electronic databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane, EMBASE, and Scopus) up to March 2025. The following terms, defined based on PICOS, were used to search the electronic databases: [“Dental Implant” AND Fibronectin AND (“Bone Regeneration” OR Osseointegration) AND (“Calcium phosphate” OR “Beta-tricalcium phosphate” OR Uncoated OR “No coating”)]. This search string was applied consistently across all databases, with minor adjustments to syntax (e.g., quotation marks, field tags) as required by each database’s search engine to ensure compatibility while maintaining the same Boolean operators (AND, OR) and search logic. The reference list of the selected articles and the “related articles” tool in PubMed were also searched manually. For the selection of studies, two evaluators assessed the titles and abstracts of articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies deemed to meet the inclusion criteria and those with doubtful information were selected and saved in Reference Manager (EndNote, version X5.0.1), and duplicate articles were removed. Then, the full text of the articles was assessed by the same evaluators independently to determine the eligibility of the study. Disagreements on the inclusion of a study between the two evaluators were resolved by consulting a third evaluator. No language or publication status restrictions were applied.

3.3. Data Extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data from included studies, including publication year, study design, animal model, implant type, surgical site, intervention details, and outcomes (e.g., bone regeneration, osseointegration metrics). Data were compiled in a standardized form, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third reviewer.

3.4. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

Risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies was assessed using the SYRCLE’s RoB tool for animal studies, which is adapted from the Cochrane RoB tool for randomized trials and tailored for preclinical research. The following domains were evaluated:

- Random sequence generation: Whether the study reported a method for random allocation of animals to intervention and control groups (e.g., random number generator or coin toss).

- Allocation concealment: Whether the allocation sequence was concealed from investigators assigning animals to groups (e.g., sealed opaque envelopes).

- Blinding of participants and personnel: Whether personnel administering interventions or caring for animals were blinded to the treatment groups.

- Blinding of outcome assessment: Whether outcome assessors (e.g., histologists or data analysts) were blinded to the intervention groups.

- Incomplete outcome data: Whether the study accounted for dropouts or missing data and whether these were balanced across groups.

- Selective reporting: Whether all pre-specified outcomes were reported, or if there was evidence of selective outcome reporting.

- Other sources of bias: Any additional factors that could introduce bias, such as baseline imbalances, inappropriate housing conditions, or funding conflicts.

Each domain was judged as having “low risk”, “high risk,”, or “unclear risk” of bias based on the study’s reporting. A study was classified as having a “low risk of bias” if it demonstrated minimal risk across all domains. “Some concerns” meant that the study was judged to raise concerns in at least one domain, but not having a high RoB for any domain. “High risk of bias” included studies which were judged to have a high RoB in at least one domain or to have some concerns for multiple domains.

4. Results

4.1. Study Selection

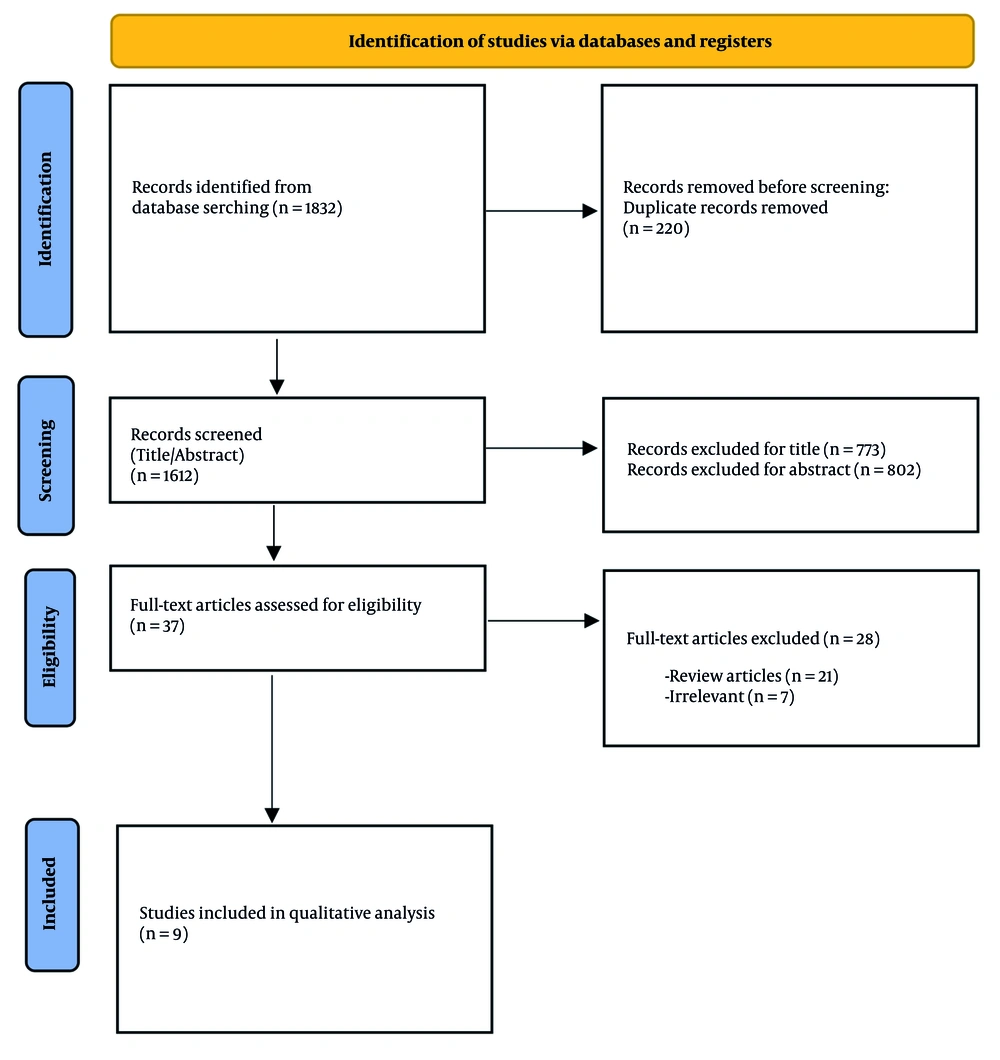

The search yielded 1,832 potentially-related titles. After removing duplicate articles, 1,612 articles remained. The titles of the remaining 1,612 articles were read; 773 were excluded due to irrelevant titles, leaving 839 articles. The abstracts of the remaining 839 articles were assessed, and 802 articles were excluded based on their abstracts. The full texts of 37 studies were obtained, and 28 studies were excluded, of which 21 were review articles. Nine articles were included in this systematic review, and their data were extracted (Table 1 and Figure 1). Nine animal studies were included, involving a total of 27 dogs, 63 rats, 6 minipigs, and 24 rabbits.

| Name and Years | Study Type | Animal | Implant Type | Surgical Site | Assessment | Follow-up | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jimbo et al. (20); 2007 | Animal study | Three male 8-week-old rats | Titanium ion-plated acrylic implant | Middle portion of the diaphysis of the left femur | Immunofluorescence staining analysis, histomorphometrically analysis, immunohistochemistry, the preparation of bone marrow stromal cells, chemotaxis assay, in vitro proliferation assay, osteogenic differentiation analysis were assessed. | After 1, 7, and 14 days | Ti-acryl implant vs. FN-Ti-acryl |

| Kim et al. (21); 2011 | Animal/ split mouth | Four males, 18- to 24-month-old mongrel dogs weighing about 30 kg each were chosen. | SLA-surface-modified titanium implants | Mandibular premolars | Histomorphometry assessed bone density and bone implant contact | After 4 and 8 weeks | Fibronectin coating vs. CaP coating |

| Lee et al. (22); 2014 | Animal study | Five males, mongrel dogs, aged 18 - 24 months and weighing approximately 30 kg, were used. | Cylindrical, threaded implants of CP-Ti | Premolars and first molars at mandibles | Histomorphometry assessed bone density and bone implant contact | After 2 and 4 weeks | Machined-surface implant and apatite-coated vs. fibronectin-loaded and apatite-coated vs. oxysterol-loaded and apatite-coated |

| ELkarargy (23); 2014 | Animal study | 12 New Zealand white mature male rabbits, weight between 2.5 - 4 kg | Titanium implants | Left limb and right limb | Scanning electron microscopy assessed gap distance between the bone and implants. | After 4 and 8 weeks | No coating vs. fibronectin coating |

| Kammerer et al. (24); 2015 | Animal study | Twelve 9-month-old, 4 to 5 kg, New Zealand white rabbits | Titanium miniscrews | Tibia | Bone histomorphometry assessed total bone-implant contact, bone-implant contact in the cortical and in the spongious bone. | After 3 and 6 weeks | No coating vs. streptavidin – biotin coating vs. streptavidin – biotin – fibronectin coated |

| Alvira-Gonzalez et al. (25); 2016 | Animal study | 18 female beagle dogs | Not stated | Premolars and first molars at mandibles | Bone histomorphometry analysis were assessed. | After 1, 2, and 3 months | β-TCP coating vs. fibronectin with β-TCP coating vs. fibronectin and adipose-derived stem cells with β-TCP coating |

| Escoda-Francoli et al. (26) ; 2018 | Animal study | 30 adult males Sprague Dawley rats | Not stated | Cranial | Histomorphometry analysis assessed augmented area gained tissue, sum of mineralized bone matrix, bone substitute, the diameter of the defect, and non‐mineralized tissue. | After 6 and 8 weeks | β-TCP coating vs. β-TCP with fibronectin coating |

| Sanchez-Garces et al. (27); 2020 | Animal study | 30 Sprague Dawley rats | Not stated | Cranial | Histomorphometry analysis assessed augmented area, gained tissue, mineralized/non mineralized bone matrix and bone substitute. | After 2 and 6 weeks | β-TCP coating vs. β-TCP with fibronectin coating |

| Schierano et al. (28); 2021 | Animal study | Six minipigs | Titanium implants | tibia | Biomolecular analysis assessed mRNA of BMP-4, BMP-7, TGF-β2, IL-1, and osteocalcin. Histological analysis assessed inflammation and osteogenesis. | After 7, 14, and 56 days | RhBMP-7 coating vs. type 1 collagen coating vs. fibronectin coating |

Abbreviations: CP-Ti, commercially pure titanium; β-TCP, beta-tricalcium phosphate; RhBMP-7, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7; TGF-β2, transforming growth factor β2; IL-1, interleukin-1.

4.2. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

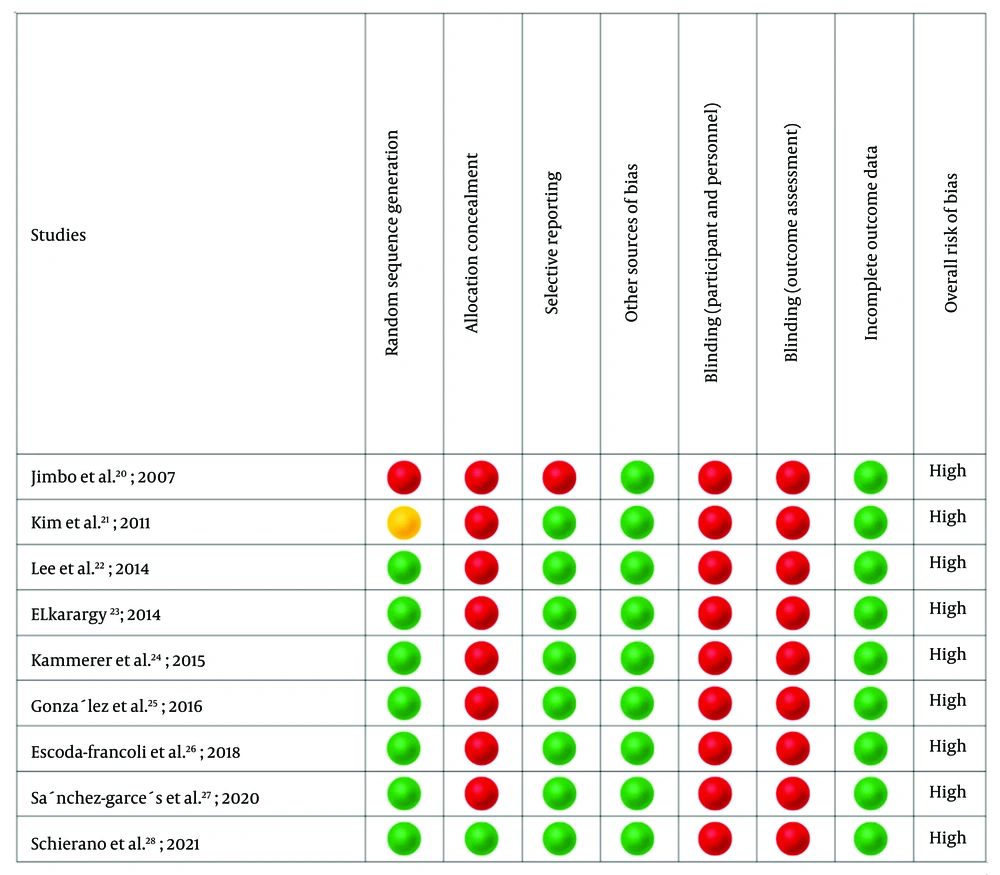

It was determined using the SYRCLE’s RoB tool (Figure 2). All nine studies had a high RoB.

4.3. Fibronectin with Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate

Three animal studies evaluated the bone regeneration potential of fibronectin combined with β-TCP in osseous defects.

4.3.1. Methods

Alvira-Gonzalez et al. (2016) conducted a study involving 18 female Beagle dogs. Cylindrical bone defects were created at the mandibular first, second, and third premolars and first molar sites. The first premolar defect served as the control group, while the remaining three sites were randomly assigned to receive β-TCP, fibronectin with β-TCP, or fibronectin combined with adipose-derived stem cells and β-TCP. Animals were euthanized at 1, 2, and 3 months post-surgery. Bone histomorphometry was performed to assess bone formation, degree of collapse, neoformed bone matrix, and medullary space (25).

Escoda-Francoli et al. (2018) included 30 adult male Sprague Dawley rats. Two bicortical critical-sized defects, each 5 mm in diameter, were created in the calvarium using a trephine bur. Of the 60 defects, 30 were filled with material, and 30 served as empty controls on the contralateral side. The rats were divided into four groups based on euthanasia time and filling material: Group 1 received fibronectin with β-TCP and was euthanized after 6 weeks; group 2 received β-TCP and was euthanized after 8 weeks; groups 3 and 4 received fibronectin with β-TCP and β-TCP, respectively, with euthanasia at 6 and 8 weeks. Primary outcomes included augmented area, gained tissue, mineralized bone matrix, and bone substitute in groups 2 and 4. Secondary outcomes, assessed in groups 1 and 3 at 8 weeks, included mineralized bone matrix, non-mineralized tissue, and bone substitute (26).

Sanchez-Garces et al. (2020) also utilized 30 adult male Sprague Dawley rats, creating two 5-mm bicortical calvarial defects per animal. Half of the 60 defects were filled with material, and the other half served as controls. The rats were divided into four groups: Group 1 received fibronectin with β-TCP and was euthanized after 2 weeks; group 2 received β-TCP and was euthanized after 8 weeks; groups 3 and 4 received fibronectin with β-TCP and β-TCP, respectively, with euthanasia at 2 and 8 weeks. Assessed parameters included defect area diameter, target area, augmented area, mineralized bone matrix, bone substitute, gained tissue, and graft perimeter (27).

4.3.2. Outcomes

Alvira-Gonzalez et al. (2016) found no statistically significant differences in total bone regeneration area, neoformed bone matrix percentage, medullary space, or contact between biomaterial and neoformed bone matrix across the four defect types at the time of euthanasia. All defects exhibited increased neoformed bone matrix over time, though without a consistent pattern. Notably, defects treated with fibronectin, adipose-derived stem cells, and β-TCP showed a significant increase in bone regeneration area at 3 months compared to 1 month (P = 0.006) (25).

Escoda-Francoli et al. (2018) analyzed 58 histological samples from 29 rats. At 8 weeks, histomorphometric analysis revealed significant increases in the augmented area for fibronectin with β-TCP and β-TCP groups compared to controls (P = 0.001 and P = 0.005, respectively). Bone turnover, expressed as a percentage within the target area, was slightly higher in the fibronectin with β-TCP group at 6 and 8 weeks but was not statistically significant (P = 0.067 and P = 0.335, respectively). The total gained tissue area (mm2) was significantly greater in the fibronectin with β-TCP group compared to β-TCP alone (P = 0.044) (26).

Sanchez-Garces et al. (2020) evaluated 60 samples, reporting a significantly larger augmented area in treatment groups compared to controls (P < 0.001). The fibronectin with β-TCP group showed a significant reduction in bone substitute area from 2 to 6 weeks (P = 0.031). Gained tissue was significantly higher in the fibronectin with β-TCP group compared to controls, both in percentage (P = 0.028) and mm2 (P = 0.011), particularly at 2 weeks (P = 0.056) (27).

4.4. Fibronectin and Calcium Phosphate

One study investigated the bone regeneration potential of fibronectin compared to calcium phosphate.

4.4.1. Methods

Kim et al. (2011) examined osseointegration in four male mongrel dogs using SLA titanium implants divided into two groups: One coated with fibronectin and the other with calcium phosphate. Histometric analysis under an optical microscope assessed bone density and bone-implant contact at 4 and 8 weeks post-implantation (21).

4.4.2. Outcomes

Kim et al. (2011) reported that all implants remained clinically stable without mobility throughout the study. Bone-to-implant contact and bone density were lower in fibronectin- and calcium phosphate-coated SLA implants compared to uncoated controls, but these differences were not statistically significant (21).

4.5. Fibronectin and Oxysterol

One study evaluated the effects of fibronectin and oxysterol on early bone healing.

4.5.1. Methods

Lee et al. (2014) studied five male mongrel dogs, installing five types of dental implants at healed alveolar ridges: Machined-surface, apatite-coated machined-surface, apatite-coated, fibronectin-loaded, oxysterol-loaded, and sand-blasted large-grit, acid-etched (SLA) implants. Histological and histometric analyses were conducted at 2 and 4 weeks to assess bone-implant contact and bone density (22).

4.5.2. Outcomes

Lee et al. (2014) observed distinct bone healing patterns at 2 weeks post-implantation. Fibronectin-loaded and sand-blasted SLA implants exhibited continuous new bone formation across their surfaces, whereas machined-surface, apatite-coated, and oxysterol-loaded implants showed minimal new bone lining with bony trabeculae extending from adjacent tissue. Histometric analysis indicated significantly lower bone-implant contact in machined-surface, apatite-coated, and oxysterol-loaded implants compared to sand-blasted SLA implants, but fibronectin-loaded implants showed comparable bone-implant contact to the latter. Bone-implant contact and bone density increased from 2 to 4 weeks, though bone density differences among groups were not statistically significant (22).

4.6. Fibronectin and Control

Three studies compared fibronectin-coated implants to uncoated controls.

4.6.1. Methods

Jimbo et al. (2007) investigated plasma fibronectin’s osseointegration effects in three male mice. Round 1-mm bone defects were created in the left femur, and titanium or fibronectin-soaked titanium implants were inserted. Animals were euthanized at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, and 14 days post-surgery. Immunofluorescence staining was performed at day 4, histomorphometric analysis (bone-implant contact and fibroblastic cell count) from days 5 to 14, and immunohistochemistry at day 2. Cell culture and chemotaxis assays were also conducted (20).

Elkarargy (2014) assessed fibronectin’s osseointegration in 12 male rabbits using scanning electron microscopy to evaluate bone-implant gaps at 4 and 8 weeks post-implantation (23). Kammerer et al. (2015) evaluated osteoconductivity in 12 rabbits using streptavidin-biotin-coated and streptavidin-biotin-fibronectin-coated titanium miniscrews in the tibia. Total bone-implant contact, cortical and spongious bone-implant contact, and linear bone fill percentage were measured at 3 and 6 weeks (24).

4.6.2. Outcomes

Jimbo et al. (2007) reported enhanced osseointegration in fibronectin-coated implants, attributed to the recruitment of fibronectin-positive cells critical for osteogenesis. The study highlighted fibronectin’s chemotactic role in promoting osteogenic cell migration and bone formation (20).

Kammerer et al. (2015) found that streptavidin-biotin-fibronectin-coated implants exhibited significantly higher cortical bone-implant contact (P = 0.043) and linear bone fill (P = 0.007) at 3 weeks compared to uncoated controls. At 6 weeks, significant differences persisted for total bone-implant contact (P = 0.016) and cortical bone-implant contact (P < 0.001). However, uncoated implants showed significantly higher spongious bone-implant contact (P < 0.001). Streptavidin-biotin-coated implants demonstrated reduced bone growth compared to both fibronectin-coated and uncoated implants (P < 0.001) (24).

Elkarargy (2014) observed a larger bone-implant gap distance in the control group compared to the fibronectin group at 4 and 8 weeks, although the difference lacked statistical significance. No significant changes in mean gap distance were noted within groups over time (23).

4.7. Fibronectin, BMP-7, and Type I Collagen

One study compared the effects of fibronectin, recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7 (rhBMP-7), and type I collagen on osseointegration.

4.7.1. Methods

Schierano et al. (2021) evaluated osseointegration in 24 tibias of six adult male minipigs. Bone samples were collected at 7, 14, and 56 days post-implantation. Biomolecular analyses assessed mRNA expression of BMP-4, BMP-7, transforming growth factor β2 (TGF-β2), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and osteocalcin in sites treated with rhBMP-7, type I collagen, or fibronectin. Histological analyses evaluated inflammation and osteogenesis (28).

4.7.2. Outcomes

Schierano et al. (2021) reported increased BMP-4 and BMP-7 expression at 7 and 14 days in sites treated with rhBMP-7 and fibronectin, with BMP-7 remaining elevated at 56 days. Type I collagen sites showed increased BMP-4 at 7 and 14 days and BMP-7 from day 14. Fibronectin consistently increased TGF-β2 expression across all time points, whereas rhBMP-7 increased it only up to 7 days. The IL-1β expression increased in collagen-treated sites from day 14. Osteocalcin levels were elevated in fibronectin-treated sites. Inflammatory infiltrates were characterized by neutrophilic granulocytes at 7 days and mononuclear cells at 14 and 56 days (28).

5. Discussion

Fibronectin, a high-molecular-weight glycoprotein integral to cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation, has emerged as a pivotal biomolecule in enhancing bone regeneration and osseointegration around dental implants. The studies included in this systematic review demonstrate that fibronectin generally promotes osseointegration and bone healing, although results vary across experimental designs and implant conditions (20-28). This section synthesizes the findings, elucidates the underlying mechanisms, addresses limitations, and proposes directions for future research.

5.1. Fibronectin with Beta-Tricalcium Phosphate

The combination of fibronectin and β-TCP consistently demonstrated enhanced bone regeneration across three studies, underscoring fibronectin’s potential as a bioactive enhancer of osteoconductive materials. Alvira-Gonzalez et al. (2016) found that fibronectin, when combined with adipose-derived stem cells and β-TCP, significantly increased bone regeneration in mandibular defects in Beagle dogs at three months (P = 0.006) compared to controls (25). This suggests a synergistic effect, where fibronectin likely enhances the regenerative capacity of stem cells by improving their adhesion and differentiation on the β-TCP scaffold. Escoda-Francoli et al. (2018) reported significant increases in augmented bone area (P = 0.001) and total gained tissue (P = 0.044) with fibronectin-coated β-TCP compared to β-TCP alone in rat calvarial defects at eight weeks, indicating that fibronectin strengthens the scaffold’s ability to support bone formation (26). Similarly, Sanchez-Garces et al. (2020) observed a significant increase in gained tissue at two weeks (P = 0.028) in fibronectin-treated rat calvarial defects, highlighting fibronectin’s role in accelerating early bone healing (27). These findings collectively suggest that fibronectin enhances the osteoconductive properties of β-TCP, likely by improving cell adhesion and recruiting osteogenic cells, thereby promoting bone formation and implant integration.

The observed improvements in bone regeneration are likely driven by fibronectin’s biological properties, particularly its ability to interact with integrins and facilitate cellular processes. Fibronectin’s integrin-binding domain (Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser sequence) promotes osteoblast adhesion and migration, creating a favorable microenvironment for bone matrix deposition (29-31). In the context of β-TCP, fibronectin may serve as a bioactive coating that enhances the scaffold’s interaction with osteogenic cells, as evidenced by the increased tissue augmentation reported by Escoda-Francoli et al. (2018) and Sanchez-Garces et al. (2020) (26, 27). The synergistic effect observed by another study with adipose-derived stem cells further supports fibronectin’s role in recruiting and promoting stem cell differentiation, potentially through integrin-mediated signaling pathways that upregulate osteogenic markers such as BMP-4 and osteocalcin, as noted in related studies (28). These mechanisms align with fibronectin’s established role in modulating the ECM to facilitate bone healing, making it a valuable adjunct to osteoconductive materials like β-TCP (30).

5.2. Fibronectin and Calcium Phosphate

Kim et al. (2011) compared fibronectin-coated implants to calcium phosphate-coated implants, finding no significant differences in bone-to-implant contact or bone density compared to uncoated controls (21). Several factors may account for the lack of significant differences in bone-to-implant contact and bone density reported by Kim et al. (2011) (21). The study’s small sample size of only four dogs likely reduced statistical power, making it difficult to detect subtle differences, particularly given the inter-individual variability common in animal studies. Additionally, the inherent osteoconductivity of SLA (sand-blasted, SLA) titanium implants, which promote robust bone integration due to their roughened surface, may have obscured any incremental benefits of fibronectin, as control implants already facilitated strong bone formation. The comparison with calcium phosphate, another osteoconductive coating, further limited the ability to isolate fibronectin’s effects, as both materials likely enhanced bone integration to a similar extent. Moreover, the study’s lack of detail regarding the fibronectin coating method — such as concentration, uniformity, or stability — suggests that suboptimal application may have reduced its bioactivity, thereby limiting its impact on bone regeneration. These factors collectively constrained the study’s ability to demonstrate fibronectin’s potential.

The findings are further limited by several methodological and design constraints. Kim et al. (2011) was assessed as having a high RoB using SYRCLE’s RoB tool, primarily due to inadequate reporting of randomization, blinding, or allocation concealment, which undermines the reliability of the results. The use of a canine model may not fully replicate human bone healing dynamics, particularly for dental implants where biomechanical loading differs, thus limiting the study’s translational relevance. Additionally, the observation periods of 4 and 8 weeks may not have captured longer-term effects of fibronectin, which could manifest beyond this timeframe. These limitations underscore the need for cautious interpretation of the findings and suggest that fibronectin’s role in bone regeneration warrants further investigation under more robust conditions (21).

5.3. Fibronectin and Oxysterol

Lee et al. (2014) demonstrated that fibronectin-loaded implants exhibited bone healing patterns comparable to sand-blasted, SLA implants, with continuous new bone formation lining the implant surface at two weeks (22). This finding is significant, as it positions fibronectin as a competitive bioactive coating compared to SLA implants, which are recognized for their strong osteoconductive properties due to their roughened surface (32). In contrast, machined-surface and oxysterol-loaded implants showed limited new bone formation, with only minimal bony trabeculae extending from adjacent tissue, suggesting that fibronectin may outperform these alternatives by promoting more robust early osteogenic activity (32, 33). The enhanced bone-to-implant contact observed with fibronectin-loaded implants highlights its ability to stimulate osteoblast differentiation and adhesion, likely through integrin-mediated signaling, which fosters a conducive microenvironment for bone matrix deposition (34).

However, the study’s implications are tempered by several limitations. A high RoB, as assessed by SYRCLE’s RoB tool, arises from inadequate reporting of randomization and blinding, which may exaggerate the observed effects. The small sample size of five dogs likely limited statistical power, particularly for detecting differences in bone density, which showed no significant improvement across groups. Additionally, the study’s focus on early healing (2 and 4 weeks) leaves the long-term impact of fibronectin unclear. The use of a canine model, while relevant, does not fully replicate human bone healing dynamics, limiting direct clinical applicability. The observed synergy between fibronectin and oxysterol suggests that combining fibronectin with other bioactive agents could enhance its osteogenic effects, particularly during the critical early healing phase (32). This finding opens avenues for exploring multi-component coatings to optimize osseointegration.

5.4. Fibronectin and Control

Studies comparing fibronectin-coated implants to uncoated controls consistently reported improved osseointegration. Jimbo et al. (2007) demonstrated that fibronectin-coated titanium implants in mice promoted osteogenesis by attracting fibronectin-positive cells, suggesting that its chemotactic properties facilitate osteogenic cell migration to the implant site, thereby enhancing bone formation (20). Similarly, Kammerer et al. (2015) found that fibronectin-coated titanium miniscrews in rabbits significantly increased cortical bone-implant contact and linear bone fill at three weeks (P = 0.043) and six weeks (P < 0.001), indicating that fibronectin enhances implant surface bioactivity, leading to stronger bone integration (24). In contrast, Elkarargy (2014) reported no significant reduction in bone-implant gap distance with fibronectin-coated implants in rabbits (P > 0.05, exact P-values not reported), possibly due to limitations in study design or insufficient sample size to detect differences (23). These findings collectively suggest that fibronectin enhances the biological interaction between implants and bone, primarily through improved cell recruitment and adhesion, though its efficacy may depend on specific experimental conditions.

Several limitations temper these findings. All studies were assessed as having a high RoB using SYRCLE’s RoB tool, primarily due to inadequate reporting of randomization, blinding, and allocation concealment, which could inflate the reported benefits. For example, Jimbo et al. (2007) used only three mice, likely reducing statistical power and increasing variability (20). The use of animal models (mice and rabbits) limits direct applicability to humans, as differences in bone physiology and loading conditions may affect fibronectin’s effectiveness (33, 34). Furthermore, variability in implant types (e.g., titanium implants versus miniscrews) and assessment methods (e.g., histomorphometry versus scanning electron microscopy) introduces heterogeneity, complicating comparisons across studies. The short follow-up periods (up to 6 - 8 weeks) in these studies also leave long-term outcomes unclear. These findings highlight fibronectin’s potential to enhance implant surface bioactivity, particularly through chemotactic and adhesive mechanisms that promote osteogenesis. However, inconsistent results, as observed in Elkarargy (2014), suggest that factors such as implant surface characteristics or coating techniques may influence outcomes. Future research should focus on standardizing fibronectin application methods, increasing sample sizes to improve statistical power, and conducting human clinical trials to validate these preclinical findings. Long-term studies are also needed to evaluate the durability of fibronectin-enhanced osseointegration, ensuring its relevance for clinical dental implant applications.

5.5. Fibronectin, Bone Morphogenetic Protein-7, and Type I Collagen

Schierano et al. (2021) demonstrated that fibronectin, when combined with rhBMP-7 and type I collagen, significantly enhanced osseointegration in minipigs (28). This finding underscores fibronectin’s potential to augment the osteogenic effects of rhBMP-7 and type I collagen, presenting a promising approach for improving dental implant outcomes in challenging regenerative scenarios. The observed upregulation of osteogenic markers suggests that fibronectin could play a pivotal role in combination therapies, particularly for patients with compromised bone quality. Future research should prioritize human clinical trials to validate these effects, alongside standardized fibronectin delivery methods and larger sample sizes to enhance statistical power and minimize bias. Additionally, long-term studies are essential to evaluate the sustained impact of this synergistic approach on implant success, further elucidating fibronectin’s role in bone regeneration for clinical applications.

5.6. Mechanisms and Broader Implications

Fibronectin’s efficacy in promoting bone regeneration, where observed, is mediated through multiple mechanisms, supported by both the included studies and external literature. Jimbo et al. (2007) demonstrated that fibronectin-coated implants enhanced osseointegration by recruiting fibronectin-positive cells, indicating a chemotactic role that facilitates osteogenic cell migration (20). Schierano et al. (2021) reported increased expression of BMP-4, BMP-7, and osteocalcin at fibronectin-treated sites, suggesting that fibronectin promotes osteoblast recruitment and differentiation, likely via integrin-mediated pathways (28, 35). External literature further supports that fibronectin’s interaction with integrins, particularly α5β1, activates intracellular signaling pathways that enhance osteoblast adhesion, migration, and differentiation (31, 36). This mechanism is critical for new bone matrix formation and achieving osseointegration. Additionally, fibronectin modulates the inflammatory response by influencing the secretion of cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which regulate osteoclastogenesis and balance bone resorption with formation (37, 38). The chemotactic properties of fibronectin, as highlighted by Jimbo et al. (2007), further contribute to its regenerative potential by attracting osteogenic cells to the implant site, promoting faster bone healing (20, 34, 36).

However, variable outcomes, as observed in Kim et al. (2011) and Elkarargy (2014), suggest that factors such as implant surface characteristics, fibronectin application methods, or study design may influence its effectiveness (21, 23). The interaction between fibronectin and the ECM creates a favorable microenvironment for bone regeneration by enhancing cellular responses and stabilizing the implant-bone interface (39, 40). When combined with other bioactive molecules, such as BMPs or type I collagen, fibronectin exhibits synergistic effects that amplify osteoblast activity and bone formation (39, 41). These findings align with the concept of biomimetic surfaces, where fibronectin enhances the bioactivity of implant materials, such as titanium or β-TCP, by mimicking the natural ECM (42-44).

5.7. Conclusions

This systematic review suggests that fibronectin generally promotes bone regeneration and osseointegration around dental implants in various animal models, with mechanisms including enhanced cell adhesion, recruitment of osteoblasts, and promotion of osteogenic differentiation through integrin-mediated signaling. However, these findings are limited by the exclusive reliance on animal studies, meaning clinical efficacy in humans remains unproven. Moreover, all included studies were assessed as having a high RoB, as determined by the SYRCLE’s RoB tool, primarily due to inadequate reporting of randomization, blinding, and allocation concealment. While fibronectin shows promise, particularly when combined with materials like β-TCP or BMP-7, further research is essential to standardize application methods, validate efficacy in clinical settings, and address methodological limitations to reduce bias. Long-term studies in humans and investigations into synergistic effects with other regenerative materials are needed to fully realize fibronectin’s potential in improving dental implant outcomes.

5.8. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the promising results in most studies, several limitations must be acknowledged. All included studies were animal-based, with an elevated RoB, as determined by the SYRCLE’s RoB tool, primarily due to inadequate reporting of randomization, blinding, and allocation concealment. The heterogeneity in study designs, animal models, and outcome measures precluded a meta-analysis, limiting the ability to quantify fibronectin’s effect size. Additionally, small sample sizes in several studies, such as Kim et al. (2011) with four dogs and Jimbo et al. (2007) with three mice, likely reduced statistical power, potentially contributing to non-significant findings in these cases (20, 21). The lack of standardized fibronectin concentrations and application methods (e.g., coating techniques, dosages) across studies further complicates comparisons and may have influenced the variability in outcomes, as seen in Kim et al. (2011) and Elkarargy (2014). These factors underscore the need for standardized protocols to enhance the reliability and reproducibility of results (21, 23).

Future research should focus on clinical studies to validate fibronectin’s efficacy in human subjects, as the current evidence is limited to animal models. Investigating optimal fibronectin delivery methods, such as controlled-release coatings or incorporation into scaffolds, could enhance its clinical applicability. Furthermore, exploring fibronectin’s synergistic effects with emerging regenerative materials, such as growth factors or stem cell therapies, may unlock new therapeutic strategies for improving osseointegration. Long-term studies are also needed to assess the durability of fibronectin-enhanced bone regeneration and its impact on implant success rates in clinical settings.