1. Background

One of the most common conditions leading to admission to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) is respiratory distress disorders arising from various etiologies (1). Although noninvasive respiratory support is generally preferred in the NICU, invasive respiratory support becomes essential in certain situations (2). In a large cohort study of extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infants, 89% required mechanical ventilation (MV) within the first 24 hours of life, and 95% ultimately needed invasive ventilation during their NICU admission (3). A multicenter randomized clinical trial (RCT) reported that 83% of ELBW newborns initially managed with noninvasive ventilation subsequently required MV and invasive ventilation during hospitalization (4). While MV is indispensable in cases of neonatal respiratory failure, it is a high-risk intervention associated with significant complications, including mortality and neurodevelopmental impairment (5).

It is ideal to extubate intubated neonates from MV as expeditiously as possible; however, the risk of reintubation remains controversial. Reintubation within 48 hours following elective extubation is defined as extubation failure (EF) (6). Increased rates of reintubation are associated with higher hospital mortality, prolonged duration on MV, extended NICU stay, and elevated hospital costs (7, 8). In preterm newborns, the EF rate ranges from 10% to 80% and is influenced by factors such as age, duration of MV before extubation, the ventilation weaning process — including accurate prediction of safe extubation timing by the clinician — and the type of post-extubation management, such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), dexamethasone, caffeine, or inhaled epinephrine (5). Additional contributing factors include pulmonary development, coordination between the respiratory center and respiratory muscles, complications, and the heart-lung interrelationship (9).

Moreover, post-extubation protocols in preterm neonates are critically important: Vocal cord edema following intubation may result in ineffective grunting (the natural defense mechanism preterm newborns use to preserve end-expiratory volume), as well as reduced respiratory drive and muscle power required to maintain sufficient functional residual capacity. Given these considerations, immediate application of continuous distending pressure (CDP) — such as CPAP, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV), or high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) — after extubation is essential. Corticosteroids may facilitate weaning from MV, but a careful risk-benefit evaluation is warranted due to the potential for adverse events, including gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal perforation, and neurodevelopmental disorders (10).

Racemic epinephrine (a mixture of l-epinephrine and d-epinephrine, with the d form being 1/12 to 1/18 as potent as the l form) induces vasoconstriction by activating both alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors on vascular smooth muscle, thereby reducing post-extubation upper airway edema (2). Some studies suggest that inhaled epinephrine does not affect the reintubation rate in neonates (11).

The EF places a substantial burden on the healthcare system, especially in these fragile preterm newborns in the NICU. Therefore, reducing the reintubation rate and facilitating successful extubation in preterm newborns, in addition to lowering the required fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) following extubation, remains a central goal — particularly in neonates at elevated risk for severe complications, such as retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).

2. Objectives

Given the paucity of RCTs to support a robust, evidence-based protocol for weaning preterm neonates from MV, we designed a RCT in our NICU to investigate the efficacy of inhaled epinephrine in the post-extubation period.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

A two-arm, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-center randomized trial was designed and conducted in the level III NICU of Shariati Hospital, a teaching referral maternal hospital affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The study was planned for the years 2021 - 2022, and patient recruitment and randomization took place between November 2021 and September 2023.

3.2. Ethical Considerations

This trial was designed and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethical Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the study design (code: IR.TUMS.CHMC.REC.1400.122), and the trial protocol was registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (code: IRCT20210607051507N4) on 17/11/2021, prior to the commencement of patient recruitment. Participation in the trial was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all parents of newborns prior to enrollment.

3.3. Study Population

All preterm infants admitted to the level III NICU of Shariati Hospital between November 22, 2021, and September 21, 2023, were considered for inclusion. A neonatologist trained in the study protocol screened new admissions daily to identify eligible infants based on predefined criteria. The inclusion criteria were gestational age ≤ 34 weeks, birth weight ≤ 1700 g, and intubation for more than three days. Exclusion criteria were chronic pulmonary, cardiac, or neurologic disease; the presence of genetic or syndromic disorders; culture-positive sepsis; unstable hypertension for gestational age; or tachycardia greater than 180 beats per minute during nebulization. Eligible infants were enrolled consecutively after obtaining written informed parental consent. All screening, enrollment, and consent procedures were documented prospectively in a study log.

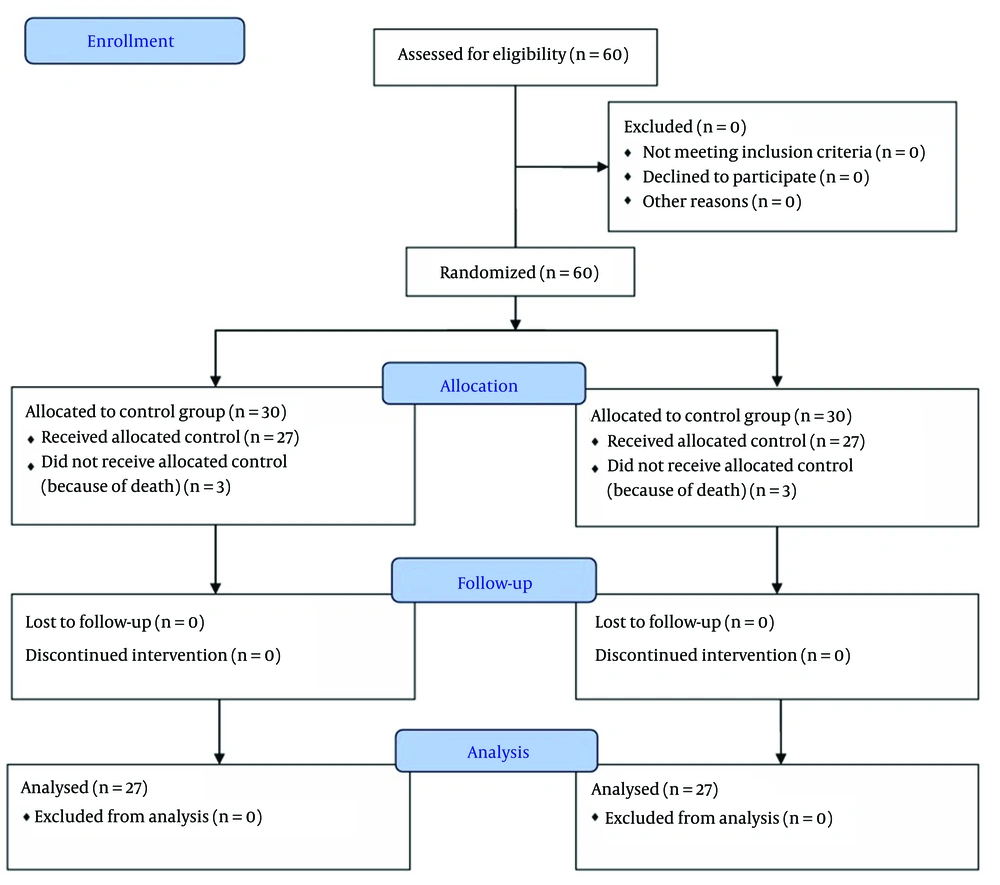

Randomization was performed immediately after obtaining consent, using sealed, opaque envelopes prepared in advance according to a block randomization scheme with equal allocation to the two groups. The neonatologist responsible for screening and enrollment was not involved in intervention administration or outcome assessment, in order to maintain blinding. Recruitment continued until the predetermined sample size was achieved. A total of 60 infants were enrolled, of whom six died before receiving the assigned intervention; therefore, 54 participants were included in the final analysis, as depicted in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 1).

In this study, the sample size was determined based on the results of a similar trial by Doyle et al. (12).

3.4. Study Arms and Randomization

A deck of cards labeled A or B, placed in sealed envelopes, was used along with a block randomization scheme designed with 15 blocks of 4 matched subjects (ABAB, AABB, ABBA, BBAA, BAAB, BABA). Patients who met the inclusion criteria were randomized into one of two study groups: The intervention group, which received inhaled epinephrine, or the placebo group, which received distilled water. Randomization was performed by an individual who was independent of the study team and had no connection to the patients or therapists. Despite the reduction in sample size, the randomization process ensured balanced allocation between the groups, resulting in a final sample of 30 neonates in each group. Before receiving the intervention, six newborns died; this attrition did not compromise the integrity of the randomization or allocation procedures.

The allocation list provided to the person responsible for intervention administration indicated both groups (epinephrine and distilled water) in syringes of identical color and appearance. The therapist, using this ordered list, remained blinded to the treatment allocation; thus, the therapist did not know which treatment was being administered to which patient.

According to our NICU post-extubation protocol, all patients received NIPPV via cannula (as cannulas are more cost-effective and accessible than nasal prongs in our country) following extubation, using the EDP-TS Neo ventilator (Ehya Darman Pishrafteh). The intervention arm received 0.5 mL per kilogram of L-epinephrine 1:10,000 as a nebulizer every 3 hours during the first day; the frequency was then tapered to every 6 hours, and subsequently every 8 hours, for a total duration of 72 hours from initiation. During nebulization, newborns were positioned prone under a headbox; immediately afterwards, the cannula was reapplied for NIPPV. The control group received an identical dose (0.5 mL per kg) of distilled water using the same nebulization method.

3.5. Outcome Variables and Measurement

Patients were followed for at least one month after admission, or longer if the duration of hospitalization was extended. The main outcomes documented and evaluated in this trial were: Reintubation due to EF (defined as reintubation within 48 hours of extubation), the FiO2 percentage required for noninvasive ventilation at 24 hours post-extubation, and partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) in arterial blood gas (ABG) at 6 hours post-extubation. Additional variables included newborn gender, weight (g), Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes, mode of delivery [normal vaginal delivery (NVD) or cesarean section (C/S)], gestational age at birth (weeks), duration of hospitalization (days), death during hospitalization, duration of intubation prior to extubation (days), respiratory rate (RR), heart rate (HR), and blood pressure.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26. Descriptive statistics were expressed as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables and mean ± SD for continuous variables. Chi-square and independent t-tests were used to compare baseline characteristics between groups. For the primary outcome (reintubation), variables of clinical importance and potential association (gestational age, birth weight, duration of MV, and sex) were included directly in a multivariable binary logistic regression model to assess the effect of inhaled epinephrine on extubation success while adjusting for key confounders. Secondary outcomes, including FiO2, were analyzed using linear regression, adjusted for gestational age, birth weight, and duration of MV. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

A total of 60 newborns were randomly assigned to two arms — intervention and placebo — each comprising 30 cases. However, six newborns did not receive the allocated intervention due to death; therefore, 54 were included in the final analysis. The frequency of reintubation was 5 (18.5%) in the intervention group and 9 (33.3%) in the control group (P = 0.214). The gestational ages of the subjects were 31.3 ± 2.3 weeks for the intervention group and 30.6 ± 2.3 weeks for the control group (P = 0.414). Additionally, the average weight of neonates was 1443.3 ± 210.1 g for the intervention group and 1330.6 ± 326.2 g for the control group (P = 0.138). The intervention group had a mean FiO2 of 24.2 ± 3.4%, which was significantly lower than that of the control group, 33.5 ± 5.3% (P < 0.001). A summary of demographic data and outcome measures for the trial arms is provided in Tables 1 and 2.

| Variables | Intervention Group | Control Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.1 b | ||

| Male | 12 (44.4) | 18 (66.7) | |

| Female | 15 (55.6) | 9 (33.3) | |

| Delivery type | 0.552 b | ||

| NVD | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | |

| C/S | 25 (92.6) | 26 (96.3) | |

| Weight (g) | 1443.3 ± 210.1 | 1330.6 ± 326.2 | 0.138 c |

| Gestational age (wk) | 31.3 ± 2.3 | 30.6 ± 2.3 | 0.414 c |

| Apgar | |||

| Minute 1 | 5.6 ± 1.9 | 5.4 ± 2.1 | 0.733 c |

| Minute 5 | 8.1 ± 1.2 | 7.6 ± 1.2 | 0.161 c |

Abbreviations: NVD, normal vaginal delivery; C/S, cesarean section.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Chi-square test.

c Independent t-test.

| Variables | Intervention Group | Control Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reintubation | 0.214 b | ||

| Yes | 5 (18.5) | 9 (33.3) | |

| No | 22 (81.5) | 18 (66.7) | |

| FiO2 (%) | 24.2 ± 3.4 | 33.5 ± 5.3 | < 0.001 c, d |

| PCO2 | 45.3 ± 5.4 | 46.0 ± 5.1 | 0.641 c |

| Hospitalization (d) | 51.4 ± 27.2 | 44.9 ± 20.0 | 0.317 c |

| Duration of MV (d) | 10.1 ± 8.1 | 9.3 ± 7.4 | 0.702 c |

| RR | 70.8 ± 5.1 | 72.5 ± 6.0 | 0.277 c |

| HR | 163.4 ± 9.1 | 161.1 ± 13.3 | 0.456 c |

| SBP | 58.3 ± 7.7 | 56.4 ± 8.0 | 0.382 c |

| DBP | 36.9 ± 5.6 | 37.3 ± 7.3 | 0.786 c |

Abbreviations: FiO2, fraction of inspired oxygen; PCO2, pressure of carbon dioxide; MV, mechanical ventilation; RR, respiratory rate; HR, heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b Chi-square test.

c Independent t-test.

d Significant at < 0.05 level.

Based on the variables included in the multivariable logistic regression model, the findings are summarized in Table 3. The effect of inhaled epinephrine on reintubation was not statistically significant (adjusted OR = 6.10 × 1018, P = 0.996). None of the other clinical variables — including birth weight, gestational age, gender, delivery type, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes, hospitalization duration, or duration of MV before extubation — showed a significant association with reintubation (P > 0.05 for all). These results suggest that within the limits of this sample, no independent predictor of reintubation could be identified.

| Variables | Multivariable Logistic Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| B | Adjusted OR | P-Value | |

| Group (epinephrine vs. placebo) | 43.255 | 6.10 × 1018 | 0.996 |

| Weight (g) | 0.029 | 1.03 | 0.998 |

| Gestational age (wk) | -2.197 | 0.111 | 0.999 |

| Gender | -2.759 | 0.063 | 1.000 |

| Delivery type | -44.284 | 0.000 | 0.999 |

| Apgar | |||

| At 1 min | 1.554 | 4.73 | 1.000 |

| At 5 min | -10.919 | 0.000 | 0.998 |

| Hospitalization (d) | 1.472 | 4.36 | 0.995 |

| Duration of MV before extubation (d) | 3.797 | 44.57 | 0.994 |

Abbreviation: MV, mechanical ventilation.

Multivariable linear regression was used to examine the factors associated with FiO2 after extubation, and the findings are presented in Table 4. Newborns who received inhaled epinephrine after extubation required significantly lower FiO2 compared with the placebo group, with an average reduction of 10.71% [95% confidence interval (CI) = -12.97 to -8.45, P < 0.001], after adjustment for other covariates. Longer duration of intubation before extubation was associated with higher FiO2 requirements (β = 0.17, 95% CI = 0.01 to 0.33, P = 0.034), and greater hospitalization duration was also positively correlated with FiO2 (β = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.02 to 0.17, P = 0.010).

| Variables | Multivariable Linear Regression | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β (Unstandardized Coefficient) | 95% CI for β | P-Value | |

| Group (epinephrine vs. placebo) | -10.71 | -12.97 to -8.45 | < 0.001 |

| Weight (g) | -0.001 | -0.007 to 0.005 | 0.745 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 0.27 | -0.54 to 1.08 | 0.500 |

| Gender | -1.80 | -4.02 to 0.43 | 0.111 |

| Delivery type | 0.92 | -3.69 to 5.53 | 0.689 |

| Apgar | |||

| At 1 min | 0.03 | -0.73 to 0.80 | 0.930 |

| At 5 min | 0.21 | -1.03 to 1.45 | 0.736 |

| Hospitalization (d) | 0.10 | 0.02 to 0.17 | 0.010 |

| Duration of MV before extubation (d) | 0.17 | 0.01 to 0.33 | 0.034 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; MV, mechanical ventilation.

5. Discussion

In this RCT, we evaluated the efficacy of inhaled epinephrine in the extubation of neonates in the NICU at Shariati Hospital. Although the rate of reintubation (the major factor in assessing successful extubation), duration of hospitalization, and partial PCO2 in ABG at 6 hours after extubation were not different between the two arms, the intervention group had a mean FiO2 of 24.2 ± 3.4 percent, which was significantly lower than that of the control group, 33.5 ± 5.3 percent (P < 0.001). This study demonstrated that the reintubation rate in the intervention arm was lower than in the placebo arm (18.5% vs. 33.3%); however, there was no statistically significant difference between inhaled epinephrine and the reintubation rate (P = 0.214). The current result is consistent with the findings of Courtney et al. (13) and Echevarria-Ybarguengoitia et al. (14). A review article by Chawla on facilitating extubation in newborns in 2009 emphasized that the routine use of inhaled epinephrine or inhaled or systemic corticosteroids as a post-extubation approach is not recommended (11), but noted that nasal CPAP and methylxanthines decrease post-EF rates in preterm newborns (11, 15).

Although many researchers have reported that the use of NIPPV after extubation reduces the rate of reintubation in preterm neonates (16-20), few studies have investigated the application of nebulized epinephrine in addition to NIPPV in the post-extubation protocol for preterm neonates in the NICU. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Kimura et al. in 2020 evaluated the role of corticosteroids in EF in children; the group receiving corticosteroids had 0.37-fold lower odds of EF, demonstrating the anti-inflammatory effect of corticosteroids on upper airway obstructions and laryngeal edema (one of the most important causes of reintubation) (21). Theoretically, inhaled epinephrine can reduce upper airway edema induced by tracheal tube irritation during MV via local vasoconstriction and restricted blood flow. Consequently, this may lead to a reduction of the reintubation rate in newborns, without the serious complications associated with steroids.

There was a significantly lower percentage of FiO2 (24.2% vs. 33.5%) required via NIPPV after 24 hours of extubation in the intervention arm compared to the placebo group. The marked difference in FiO2 requirement via noninvasive ventilation after extubation highlights the potential to reduce severe complications arising from high oxygenation in preterm neonates, such as ROP. Yucel et al. reported that, among 2186 newborns evaluated from 2012 to 2020, the incidence of any stage of ROP was 43.5%, and ROP requiring treatment was 8.0%. These percentages in ELBW infants were 81.1% and 23.9%, respectively. The ROP has many risk factors, with high oxygen saturation being one of the major contributors (22).

A Cochrane review in 2002 concluded that there were no randomized or quasi-randomized trials meeting their inclusion criteria to evaluate the effect of inhaled epinephrine on clinical outcomes after extubation of newborns, such as the rate of oxygen requirement, respiratory support, or side effects (23).

Our study found that the duration of MV before extubation was not significantly associated with the odds of reintubation (adjusted OR = 44.57, P = 0.994). Although the point estimate suggested higher odds of reintubation with longer ventilation duration, the association was not statistically significant and should be interpreted with caution, given the small sample size and wide variability. These findings contrast with those of Costa et al. (24), who reported that shorter durations of MV were associated with a higher risk of EF, suggesting that premature extubation before adequate stabilization may increase the likelihood of reintubation. These differences may reflect variations in patient populations, extubation criteria, or clinical practice. In our study, gestational age was not significantly associated with the odds of reintubation (adjusted OR = 0.111, P = 0.999). Although the direction of the effect suggested a potential protective role of greater maturity against reintubation, this association was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, our findings are consistent in direction with those of the Manley et al. study, which mentions that higher gestational age is related to extubation success (25).

To the best of our knowledge, no RCTs have evaluated the efficacy of inhaled epinephrine in addition to NIPPV as a routine post-extubation protocol for preterm neonates in the NICU. Moreover, we did not observe any adverse effects, such as tachycardia or high blood pressure, with this epinephrine dosage. This finding is consistent with the studies by Kao et al. and Moresco et al. (26, 27) on the safety of inhaled epinephrine in the treatment of transient tachypnea of newborns (TTN), which similarly reported no adverse effects. However, they investigated lower inhaled epinephrine dosages in term newborns, in contrast to our higher dosage in preterm neonates.

Our study had limitations. The small sample size reduced the statistical power to detect potential differences between groups and may have contributed to the wide CIs observed. In addition, numerous unmeasured factors may affect the process of newborn extubation from MV in the NICU, such as the stage of lung development and the coordination between the neonate’s respiratory center and lung muscles. Unfortunately, we did not follow up with neonates for ROP or complications related to high FiO2 during hospitalization. Therefore, it is recommended that larger randomized controlled trials be conducted in this field to assess the relationship between inhaled epinephrine and lower FiO2 percentage after extubation in preterm newborns, as well as the rate of neonatal complications, especially ROP.

5.1. Conclusions

To sum up, there is no significant difference in reintubation rates between the intervention arm receiving inhaled epinephrine and the placebo group. However, the marked difference in FiO2 requirement via noninvasive ventilation after extubation highlights the potential to reduce severe complications arising from high oxygenation in preterm neonates, such as ROP. Moreover, due to the absence of any adverse effects with this dosage of epinephrine, the use of nebulized epinephrine as an adjuvant method with NIPPV in the post-extubation protocol for preterm newborns in the NICU is suggested. Indeed, future larger randomized controlled trials will be necessary to assess the cost/benefit of this method, as well as to monitor for ROP complications.