1. Background

Aging leads to declines in sensory, cognitive, and motor functions that can impair balance and daily activities in older adults (1). Reduced balance confidence is linked to poorer physical and psychological outcomes (2, 3). Caregivers' low confidence further limits physical activity (4). While interventions like Tai Chi show some benefit, overall results are mixed, especially in sedentary older adults, highlighting the need for effective rehabilitation (5, 6).

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a promising, non-invasive method for enhancing cognitive and motor functions in the elderly. It uses a low-intensity electrical current over the cortex to modulate neuronal excitability. Anodal stimulation of motor and prefrontal cortices improves balance, postural control, and gait in older adults (7-9). A meta-analysis confirmed the broad efficacy of tDCS across cognitive and motor domains; however, personalized protocols are often necessary (10, 11).

Alongside this technique, mind-enhancing yoga, also known as super brain yoga, has emerged as a non-invasive method for improving balance and overall well-being in older adults. This form of yoga combines physical exercises, breathing techniques, and mental focus to strengthen the connection between the mind and body (12). Super brain yoga has been particularly effective in enhancing cognitive and physical health in the elderly. Studies indicate that these exercises can significantly improve static and dynamic balance in older adults. By enhancing coordination between the mind and body, this mental exercise also boosts self-confidence in older individuals. It helps them maintain better balance in daily life (13). Research has shown that super brain yoga may specifically improve balance and reduce the risk of falls among the elderly (13).

Despite numerous studies demonstrating the positive effects of tDCS and mind-enhancing yoga on balance in older adults, significant research gaps remain. Most notably, there is an absence of standardized tDCS protocols specifically tailored for the elderly, which limits reproducibility and clinical adoption. Additionally, while each intervention has shown beneficial outcomes independently, a direct, head-to-head comparison assessing their effects on both balance and balance confidence in older adults has not yet been conducted. It remains unclear whether tDCS or behavioral approaches such as yoga are more effective for improving sensorimotor outcomes — particularly in sedentary older adults, who are most at risk for balance impairment and associated complications (8). Clarifying this gap is essential for informing best practices in geriatric rehabilitation. Further research should directly compare these two methods to identify the best approach for improving balance and confidence in sedentary older adults (14). Using both techniques together may yield even better results in elderly rehabilitation (13).

2. Objectives

This study directly compares the effectiveness of tDCS and mind-enhancing yoga (super brain yoga) for improving both balance and balance confidence in sedentary older adults. The primary research question is: Which intervention is more effective at enhancing balance performance and confidence in this population? The results will inform best practices for rehabilitation programs targeting sedentary older adults to improve their quality of life.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sample Size

This quasi-experimental study was conducted in 2022 among adults aged 60 to 70 years registered with comprehensive health service centers in Mashhad, Iran. The sample size was determined by a power analysis using G*Power software. The calculation, based on a one-way ANOVA (power = 80%, α = 0.05, effect size η2 = 0.25 from previous tDCS and yoga studies), indicated that 30 participants would be required to detect moderate group differences.

3.2. Participants and Group Allocation

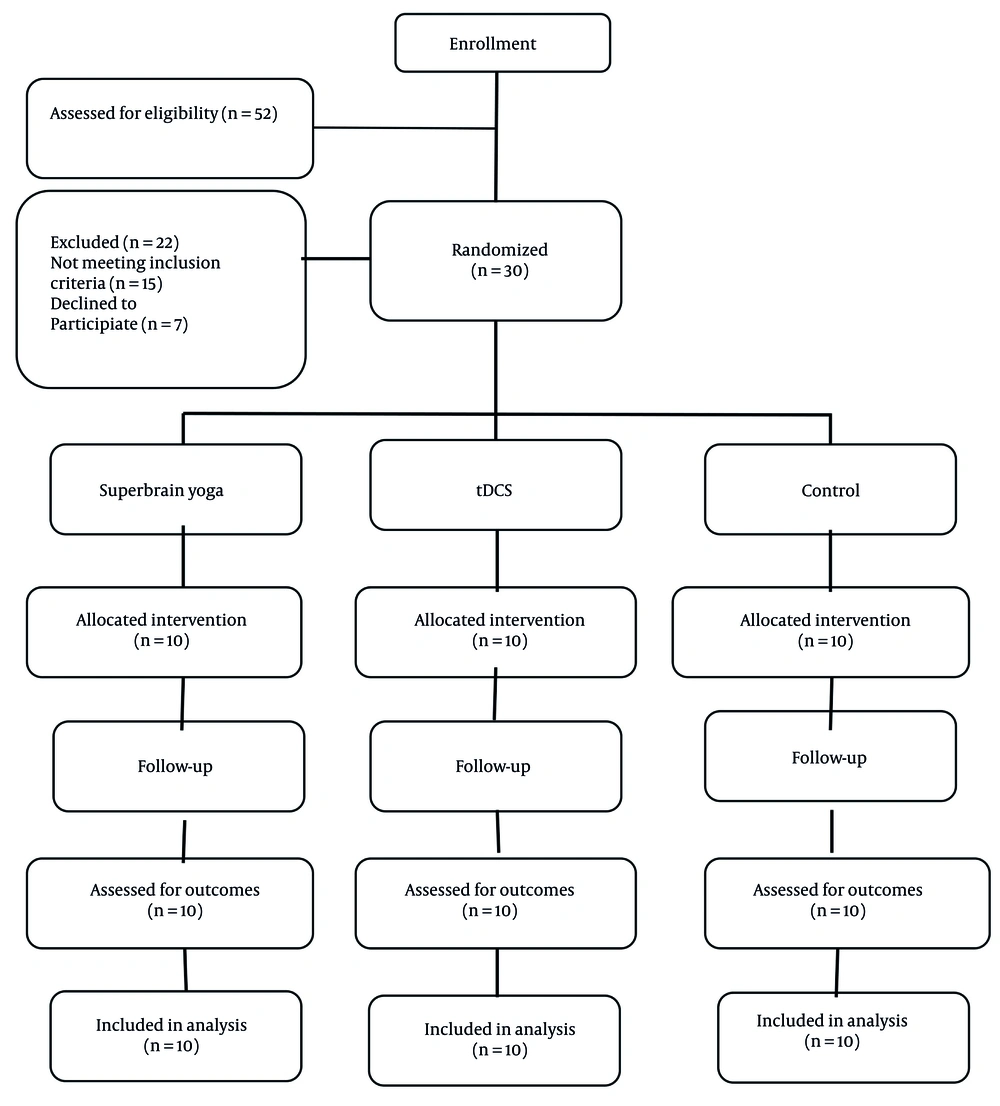

Participants were recruited through convenience sampling, using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. They were then randomly assigned to one of three groups (n = 10 each): Super brain yoga, tDCS, or a control group. The study's goal was to compare the independent effects of each intervention. A combined intervention group was not included, ensuring clear attribution of outcomes. Although past physical activity history was not a criterion, all participants were classified as physically inactive at baseline. Their initial activity levels were recorded to verify group comparability. Due to limited resources, a sham tDCS group was not included; this limitation is acknowledged.

3.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants were eligible if they were aged 60 - 70 years, scored above 23 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), could independently perform daily activities, and were in stable health without any medications that affected balance or cognition. Exclusion criteria were neurological or musculoskeletal disorders (such as epilepsy, vertigo, or joint instability), severe visual or hearing impairments, metal implants in areas relevant to electrode placement, missing more than two intervention sessions, or voluntary withdrawal from the study.

3.4. Assessment Tools

Several validated instruments were used for screening and data collection. First, the Informed Consent Form documented participants' voluntary agreement to participate in the study. Following this, the Medical History Questionnaire gathered information on neurological, musculoskeletal, sensory conditions, and medication use (15). To further assess cognitive function across various domains — including orientation, memory, attention, language, and visuospatial ability — the Persian version of the MMSE was administered; only participants scoring above 23 were included (16). Finally, balance and balance confidence were evaluated using the Activities-specific Balance Confidence (ABC) Scale and the Flamingo Balance Test, with further details provided in the "Measurement Tools" section.

3.5. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Device

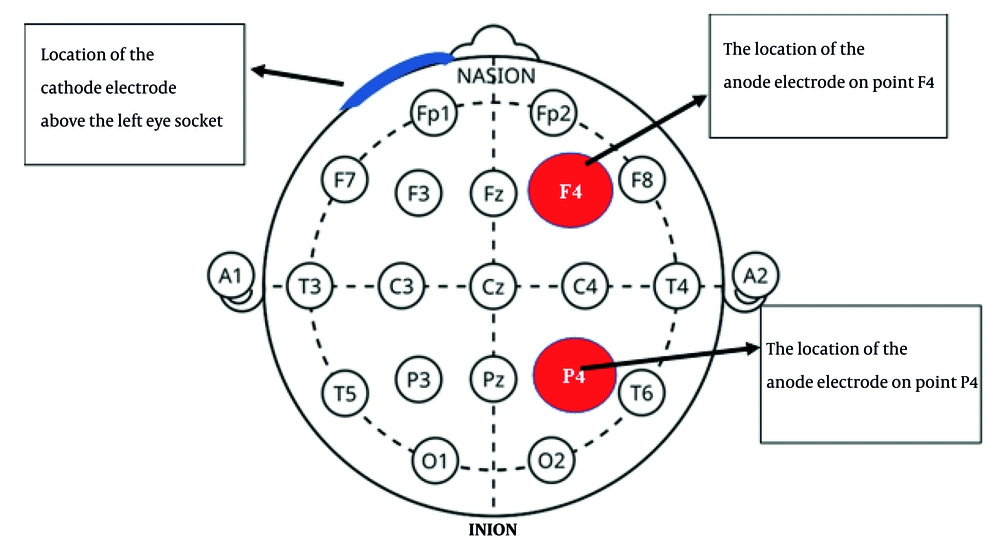

Brain stimulation was administered using the Neuristim Model 2 tDCS device, delivering a constant current of 1 mA through 3.5 × 3.5 cm saline-soaked sponge electrodes (17). The anodal electrode was placed over F4, corresponding to the right primary motor cortex (M1) of the dominant hemisphere, while the cathodal electrode was placed above the left supraorbital area (forehead), in accordance with the international 10 - 20 EEG system. This configuration produced a current density of 0.029 mA/cm2. All sessions were supervised; Electrode placement is illustrated in Figure 1 (18).

3.6. Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Questionnaire

Balance confidence was assessed using the ABC Scale, a validated 16-item instrument that measures individuals' perceived confidence in performing daily activities without losing balance. Each item is rated on a scale from 1 (no confidence) to 4 (complete confidence), and the scores for all 16 items are summed to yield a total score ranging from 16 to 64; higher scores indicate greater confidence. This tool is widely used to estimate fall risk and guide balance-related interventions in older adults. Individual responses were recorded and scored at baseline and post-intervention without applying a shared reference time (19).

3.7. Balance Assessment

Static balance was assessed using the Flamingo balance test. Participants stood on their dominant leg with their hands on their hips and lifted the opposite leg. The duration (in seconds) that they maintained balance without touching the ground or losing posture was recorded as the score. Each participant performed the test once before and once after the intervention. Tests occurred under standardized conditions and at a consistent time, ensuring a common baseline for all subjects.

3.8. Research Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants were assigned to their groups for a eight-week intervention, which began immediately following assignment. Each group attended three weekly sessions, held at the same time and on the same day each week throughout the intervention. The tDCS group received 15-minute brain stimulation sessions, with no concurrent physical or cognitive activities. The super brain yoga group completed a 15-minute routine that consisted of a warm-up, 14 repetitions of exercises, and a relaxation segment. The control group continued their usual daily activities with no intervention during this period. A sham or low-intensity control group was not included due to resource limitations, which is acknowledged as a limitation. Protocol adherence was monitored with electronic reminders and verbal follow-up. Blinded assessors recorded balance and confidence measures at baseline and immediately after the eight-week period. Figure 2 presents a CONSORT-compliant flow diagram outlining participant recruitment, allocation, and retention.

3.9. Mind-Enhancing Yoga Training Program

The super brain yoga intervention used Sui's (2005) protocol (20). It included 3 minutes of joint warm-up, 10 minutes of yoga (14 squats with earlobe stimulation), and 2 minutes of guided yoga nidra relaxation. Each session lasted about 15 minutes and took place three times per week for eight weeks. To ensure standardization, participants received clear verbal and visual instructions. A trained researcher supervised all sessions to monitor squat depth, breathing, and earlobe pressure, providing real-time corrections to maintain consistency.

3.10. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Training Protocol

The tDCS intervention utilized a 1 mA constant current, delivered through 3.5 × 3.5 cm (35 cm2) saline-soaked sponge electrodes, resulting in a current density of 0.029 mA/cm2. The anode was placed over the F4 region (right frontal cortex, corresponding to the primary M1 of the dominant hemisphere), and the cathode was positioned above the contralateral eyebrow (supraorbital area of the non-dominant hemisphere), following the 10 - 20 EEG system. Each session lasted 15 minutes and occurred three times per week for eight weeks (12 sessions total) (21, 22). Stimulation started with a 10-second ramp-up to 1 mA and ended with a 5-second ramp-down. Electrodes were secured with adjustable straps, and a supervisor ensured correct placement and participant safety.

3.11. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and ranges, were calculated to summarize the characteristics of the data before and after the intervention. The normality of data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances was evaluated using Levene’s test. To analyze the research hypotheses, descriptive statistics, ANCOVA, Bonferroni post-hoc tests, and paired t-tests were conducted using SPSS version 24, with the significance level set at P ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

Table 1 presents descriptive information about the participants' age and physical activity level. The results of the one-way ANOVA test showed no statistically significant differences in age and physical activity levels between the groups (P > 0.05), indicating that the groups were homogeneous in terms of these key measured variables.

| Variables | Min-Max | Mean ± SD | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.27 | 0.764 | ||

| Yoga | 60.00 - 70.00 | 63.50 ± 3.47 | ||

| tDCS | 60.00 - 71.00 | 64.40 ± 4.06 | ||

| Control | 60.00 - 70.00 | 64.70 ± 3.80 | ||

| Physical activity level | 0.71 | 0.497 | ||

| Yoga | 297.00 - 990.00 | 672.50 ± 285.71 | ||

| tDCS | 297.00 - 990.00 | 521.10 ± 278.02 | ||

| Control | 297.00 - 990.00 | 616.50 ± 293.85 |

Abbreviation: tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics of the main research variables, including balance and balance confidence, across different training groups.

| Variables | Pre-test | Post-test |

|---|---|---|

| Balance | ||

| Anterior-Posterior Index | ||

| Yoga | 1.36 ± 0.45 | 1.22 ± 0.40 |

| tDCS | 1.19 ± 0.41 | 1.21 ± 0.38 |

| Control | 1.32 ± 0.34 | 1.28 ± 0.28 |

| Medial-Lateral Index | ||

| Yoga | 1.11 ± 0.35 | 0.99 ± 0.33 |

| tDCS | 1.10 ± 0.41 | 1.12 ± 0.44 |

| Control | 1.11 ± 0.36 | 1.11 ± 0.34 |

| Overall Index | ||

| Yoga | 1.80 ± 0.60 | 1.46 ± 0.45 |

| tDCS | 1.66 ± 0.55 | 1.54 ± 0.50 |

| Control | 1.56 ± 0.60 | 1.49 ± 0.53 |

| Stork test | ||

| Yoga | 2.52 ± 0.60 | 3.07 ± 0.77 |

| tDCS | 2.15 ± 0.70 | 2.53 ± 0.97 |

| Control | 2.24 ± 0.48 | 2.45 ± 0.81 |

| Balance confidence | ||

| Yoga | 82.70 ± 8.79 | 85.80 ± 7.28 |

| tDCS | 82.40 ± 9.21 | 86.10 ± 6.83 |

| Control | 79.80 ± 7.74 | 80.50 ± 8.36 |

Abbreviation: tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Table 3 presents the results of the ANCOVA assumptions for balance and balance confidence. The results showed that all tests for data normality (Shapiro-Wilk), homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test), and homogeneity of regression slopes across different groups and test phases were not statistically significant (all P > 0.05). These results indicate that the necessary assumptions for conducting ANCOVA were met for all indices and groups.

| Variables | Shapiro-Wilk Statistic | Shapiro-Wilk P | Levene’s Statistic | Levene’s P | Regression Slope F | Regression Slope p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance; AP Index | 1.14 | 0.332 | 0.49 | 0.617 | ||

| Yoga | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.92 | 0.435 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.95 | 0.719 | ||||

| tDCS | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.90 | 0.270 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.92 | 0.365 | ||||

| Control | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.93 | 0.513 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.92 | 0.406 | ||||

| Balance; ML Index | 1.03 | 0.370 | 1.05 | 0.365 | ||

| Yoga | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.95 | 0.701 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.90 | 0.272 | ||||

| tDCS | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.89 | 0.181 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.86 | 0.080 | ||||

| Control | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.90 | 0.224 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.88 | 0.162 | ||||

| Balance; OverallIndex | 1.76 | 0.191 | 2.96 | 0.071 | ||

| Yoga | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.95 | 0.696 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.92 | 0.407 | ||||

| tDCS | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.96 | 0.829 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.95 | 0.690 | ||||

| Control | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.94 | 0.607 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.94 | 0.572 | ||||

| Stork test | 0.80 | 0.456 | 0.53 | 0.593 | ||

| Yoga | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.86 | 0.076 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.89 | 0.170 | ||||

| tDCS | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.90 | 0.249 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.92 | 0.408 | ||||

| Control | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.86 | 0.098 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.96 | 0.883 | ||||

| Balance confidence | 0.10 | 0.903 | 1.10 | 0.340 | ||

| Yoga | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.91 | 0.284 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.92 | 0.367 | ||||

| tDCS | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.92 | 0.358 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.88 | 0.133 | ||||

| Control | ||||||

| Pre-test | 0.88 | 0.159 | ||||

| Post-test | 0.88 | 0.146 |

Abbreviation: tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

Table 4 presents the univariate ANCOVA results for the effect of training interventions on balance measures. The results indicated that the training interventions had a significant effect on the Anterior-posterior Balance Index (P = 0.008), the Overall Balance Index (P < 0.0001), and balance confidence (P = 0.002). These indices showed moderate to large effect sizes. However, no significant differences were observed between groups for the Medial-lateral Balance Index (P = 0.034) and the Stork test (P = 0.470), and the effect sizes were small.

| Variables | Sum of Squares | Source | df | Mean Square | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance | Group | ||||||

| AP Index | 0.10 | 2 | 0.05 | 5.92 | 0.008 | 0.313 | |

| ML Index | 0.12 | 2 | 0.06 | 3.85 | 0.034 | 0.229 | |

| Overall Index | 0.31 | 2 | 0.15 | 14.22 | < 0.0001 | 0.523 | |

| Stork test | 0.45 | 2 | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.470 | 0.056 | |

| Balance confidence | 65.46 | Group | 2 | 32.73 | 7.65 | 0.002 | 0.371 |

Table 5 presents the Bonferroni post-hoc test results for balance and balance confidence variables. The results showed that the yoga group had a significant difference in the Anterior-posterior Balance Index compared to the tDCS group (P = 0.008) but not with the control group (P = 0.065). For the Medial-lateral Balance Index, none of the groups showed significant differences (all P > 0.05). Regarding the Overall Balance Index, the yoga group differed significantly from both the tDCS (P = 0.001) and control (P < 0.0001) groups. At the same time, no significant difference was observed between the tDCS and control groups (P = 0.999). No significant differences were found between any of the groups in the Stork test (all P = 0.999 and 0.685). Finally, in balance confidence, the yoga group showed a significant difference compared to the control group (P = 0.015), and the tDCS group also differed significantly from the control group (P = 0.003). However, there was no significant difference between the yoga and tDCS groups (P = 0.999).

| Variables | Mean Difference | Standard Error | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balance | |||

| AP Index | |||

| Yoga | |||

| tDCS | -0.14 | 0.04 | 0.008 |

| Control | -0.10 | 0.04 | 0.065 |

| tDCS | |||

| Control | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.999 |

| ML Index | |||

| Yoga | |||

| tDCS | -0.13 | 0.05 | 0.058 |

| Control | -0.12 | 0.05 | 0.088 |

| tDCS | |||

| Control | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.999 |

| Overall Index | |||

| Yoga | |||

| tDCS | -0.20 | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| Control | -0.23 | 0.04 | < 0.0001 |

| tDCS | |||

| Control | -0.03 | 0.04 | 0.999 |

| Stork test | |||

| Yoga | |||

| tDCS | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.999 |

| Control | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.685 |

| tDCS | |||

| Control | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.999 |

| Balance confidence | |||

| Yoga | |||

| tDCS | -0.55 | 0.92 | 0.999 |

| Control | 2.85 | 0.93 | 0.015 |

| tDCS | |||

| Control | 3.41 | 0.93 | 0.003 |

Abbreviation: tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

Table 6 presents the paired sample t-test results for comparing balance levels before and after training. The results showed that the yoga group had significant improvements in the Overall Balance Index (P < 0.0001, d = 1.67) and balance confidence (P = 0.005, d = 1.15), while the tDCS group showed significant improvements in the Overall Balance Index (P = 0.003, d = 1.30) and balance confidence (P = 0.004, d = 1.24), demonstrating large and meaningful effects. Additionally, the yoga group showed significant improvements in the Anterior-posterior Balance Index (P = 0.016, d = 0.92) and Stork test (P = 0.015, d = 0.94), while the tDCS group showed significant changes in the Stork test (P = 0.034, d = 0.78), indicating moderate effects. In contrast, the control group showed no significant changes in any of the variables (all P > 0.05), indicating no effect in this group. These results highlight the strong and significant impact of both yoga and tDCS interventions on balance and balance confidence in inactive older adults, while the control group showed no effect.

| Variables | Mean Difference | df | t | P-Value | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance | |||||

| AP Index | |||||

| Yoga | 0.14 | 9 | 2.94 | 0.016 a | 0.92 |

| tDCS | -0.02 | 9 | -1.10 | 0.299 | 0.34 |

| Control | 0.03 | 9 | 1.20 | 0.258 | 0.38 |

| ML Index | |||||

| Yoga | 0.12 | 9 | 2.44 | 0.037 a | 0.77 |

| tDCS | -0.02 | 9 | -0.55 | 0.591 | 0.17 |

| Control | -0.009 | 9 | -0.28 | 0.779 | 0.09 |

| Overall Index | |||||

| Yoga | 0.34 | 9 | 5.29 | < 0.0001 a | 1.67 |

| tDCS | 0.11 | 9 | 4.11 | 0.003 a | 1.30 |

| Control | 0.06 | 9 | 1.91 | 0.089 | 0.60 |

| Stork test | |||||

| Yoga | -0.54 | 9 | -2.98 | 0.015 a | 0.94 |

| tDCS | -0.38 | 9 | -2.49 | 0.034 a | 0.78 |

| Control | -0.21 | 9 | -1.23 | 0.249 | 0.39 |

| Balance confidence | |||||

| Yoga | -3.10 | 9 | -3.65 | 0.005 a | 1.15 |

| tDCS | -3.70 | 9 | -3.92 | 0.004 a | 1.24 |

| Control | -0.70 | 9 | -1.65 | 0.132 | 0.52 |

Abbreviation: tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

a Indicates statistically significant difference at P ≤ 0.05 level.

5. Discussion

This study directly compared the effects of tDCS and mindfulness-based yoga on balance and balance confidence in inactive older adults. While both interventions significantly improved balance indicators, mindfulness-based yoga provided greater enhancements in anterior-posterior, medial-lateral, and overall balance indices. In contrast, tDCS produced significant gains in the Overall Balance Index and the Stork test, but not in specific directional indices. Furthermore, paired-sample t-test results indicated that balance confidence significantly increased after both interventions (yoga and tDCS) among inactive older adults.

ANCOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc analyses revealed that the mindfulness-based yoga group exhibited significantly greater improvements in several specific balance indices compared to the tDCS group. However, for some indices, the yoga group did not differ significantly from the control group. The neurophysiological mechanism underlying tDCS efficacy may involve anodal stimulation of the primary M1, which is known to enhance corticospinal excitability. This can facilitate sensorimotor integration and improve proprioceptive feedback, thereby contributing to improved postural control and balance (23, 24).

These findings suggest that both methods improve balance in inactive elderly individuals, with mindfulness-based yoga exhibiting a greater impact in certain measures. This may influence rehabilitation program design and highlights the effectiveness of both interventions in improving balance and confidence in this group.

Mindfulness-based yoga may improve activation of the vestibular system through dynamic postures, enhance proprioceptive input with coordinated limb movements, and strengthen cognitive-motor coupling via mindful attention and controlled breathing. Together, these factors improve neuromuscular coordination and balance (25). The findings of the present study are consistent with previous research. Specifically, Shin reported in their meta-analysis that yoga exercises have significant positive effects on muscle strength and balance in older adults, particularly in improving lower-body balance. Similar to the current findings, their study highlighted the significant impact of yoga on improving balance and mobility among the elderly (26).

Likewise, Bai et al. found that combined aerobic and resistance training significantly improved physical performance and balance in older adults. Similarly, the present study found that mindfulness-based yoga significantly improved various balance indices in inactive elderly individuals, supporting Bai et al. (27). This study’s tDCS results align with those of Zandvliet et al. (2018), who found that stimulating balance-related brain areas improves static balance. Similarly, another study found that yoga improved static and dynamic balance in older adults. These findings support the use of tDCS and yoga as a means of improving balance in the elderly (28).

Some results differ from previous studies. Asadi Samani et al. found that resistance training and square-stepping improved balance. However, in this study, the tDCS and control groups did not differ in the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral indices (29). These differences may result from research protocols, duration, or study samples. For example, the five tDCS sessions here may not have been enough to cause major changes.

Regarding balance confidence, the study's results align with those of Yousefi et al. (2018) (30). Yousefi et al. found that anodal tDCS with balance training improved balance confidence in older adults. Similarly, another study (30) reported that Pilates and square-stepping exercises enhanced physical and cognitive functioning, including balance confidence, in the elderly. Consistent with these studies, the current research found that tDCS and mindfulness-based yoga improved balance confidence in inactive older adults.

This study contributes to the literature by directly comparing tDCS and mindfulness-based yoga, highlighting key differences in their practical applications in elderly care. While both interventions improved balance and confidence in inactive older adults, mindfulness-based yoga demonstrated greater suitability for large-scale use in low-resource settings due to its accessibility, lower cost, and broader impact on balance dimensions. These findings inform healthcare professionals and program designers, indicating that both interventions can be integrated into fall prevention and mobility programs, though mindfulness-based yoga may be more practical and scalable for promoting stability and confidence in older populations.

One limitation of this study was the small sample size from a single geographic area, which may restrict generalizability. The eight-week duration of both tDCS and yoga interventions may not have been sufficient to allow for lasting changes in balance or confidence. Additional limitations include a lack of long-term follow-up, blinding, and a sham tDCS group, which limits the interpretation of results. Confounding variables, such as health status and medication use, may have influenced outcomes.

To address these limitations, future studies should evaluate the long-term effects of these methods. Researchers should increase sample size and include diverse control groups to improve accuracy and generalizability. Further research on the combined effects of tDCS and mindfulness-based yoga, along with careful monitoring of side effects, could yield new insights and directions.

5.1. Conclusions

This study showed that both tDCS and mindfulness-based yoga improve balance and balance confidence in inactive older adults. Mindfulness-based yoga improved specific balance indices more than tDCS. The tDCS also significantly improved overall balance and Stork test results. These findings align with earlier research, which has shown that physical training and brain stimulation can enhance balance in the elderly. Choosing between these methods should be based on individual needs and circumstances. Combining approaches may enhance outcomes. Mindfulness-based yoga is especially recommended due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ease of integration into daily routines, making it a practical option for fall prevention and rehabilitation.