1. Background

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has profoundly impacted global health, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. Although individuals of all ages are susceptible, evidence indicates that children generally experience milder symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection than adults. Nevertheless, a serious complication known as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) can develop (1). The MIS-C is characterized by severe systemic inflammation, fever, hypotension, and cardiac dysfunction, with features that may overlap with Kawasaki disease, macrophage activation syndrome, and toxic shock syndrome. The MIS-C frequently leads to multi-organ dysfunction and often presents with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea. Although non-specific, these symptoms can facilitate early identification and improve clinical outcomes (2). Systematic reviews report that a high proportion of patients with MIS-C exhibit GI manifestations; one such review found that up to 71% of patients had GI involvement, including abdominal pain (~ 34%) and diarrhea (~ 27%) (3). Another meta-analysis showed that GI symptoms were present in approximately one-third of pediatric COVID-19 cases, rising to nearly 80% in those diagnosed with MIS-C (4). A single-center cohort study of 44 MIS-C patients reported that GI symptoms were a major presenting feature in roughly 80% of cases (4). A comprehensive review of 27 studies encompassing 917 MIS-C cases identified GI symptoms in 87% of cases [95% confidence interval (CI): 82.9 - 91.6%] (5).

The pathophysiology of GI symptoms in MIS-C likely involves several mechanisms. The SARS-CoV-2-triggered hyperinflammation leads to cytokine release syndrome, which can cause widespread inflammation in the GI tract (6). Elevated cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), may disrupt the gut barrier, resulting in symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, and ileus (7). Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 can directly infect enterocytes via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, further contributing to GI dysfunction. The MIS-C often results in multiple organ failure, particularly affecting the cardiovascular system, leading to hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, myocarditis, or coronary artery lesions. Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial. Although numerous global studies report that GI involvement is a frequent manifestation of MIS-C, data from Iran, particularly its southern provinces, are scarce. Understanding the prevalence and pattern of GI symptoms in these patients can improve early recognition and clinical management.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and types of GI symptoms in children diagnosed with MIS-C at Bandar Abbas Children’s Hospital between 2020 and 2022, to provide region-specific evidence that complements existing literature and guides pediatric practice in similar settings.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This descriptive cross-sectional study involved 209 children diagnosed with MIS-C at Bandar Abbas Children’s Hospital between 2020 and 2022. Researchers performed a retrospective review of hospital records to identify eligible cases.

3.2. Participants

All medical records of children admitted from March 2020 to December 2022 with a final diagnosis of MIS-C were screened. Diagnosis was confirmed based on clinical documentation, laboratory test results, and epidemiological data recorded at admission. Trained research staff used a standardized data collection form to ensure consistency and accuracy.

3.3. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were patients aged 1 month to 14 years, admitted to this hospital, and diagnosed with MIS-C according to the WHO case definition, incorporating:

1. Clinical criteria: Age < 21 years; subjective or documented fever (≥ 38.0°C); clinical severity requiring hospitalization; evidence of systemic inflammation; and new onset manifestations in at least two organ systems (e.g., cardiac, mucocutaneous, shock, GI, and hematologic).

2. Laboratory criteria: Detection of SARS-CoV-2 via RT-PCR, specific antigen test, or specific serology.

3. Epidemiological criteria: Close contact with a confirmed or probable COVID-19 case within 60 days prior to hospitalization (8).

3.4. Data Collection

Data were extracted from medical records, including physicians’ clinical notes, nursing records, laboratory reports, and imaging findings. The GI symptoms were identified through documented clinical observations and diagnostic notes, including reports of:

1. Vomiting: ≥ 2 episodes within 24 hours.

2. Diarrhea: ≥ 3 watery stools in 24 hours.

3. Abdominal pain: Reported or clinically observed.

4. Ileus and GI bleeding were also recorded based on clinical diagnosis.

Liver enzyme elevation was defined as ALT or AST > 40 U/L, ALP > 350 U/L (< 10 years) or > 450 U/L (10 - 15 years), and total bilirubin > 1.2 mg/dL (9). These symptoms and abnormalities were documented based on the initial clinical presentation upon admission or during hospitalization.

3.5. Sample Size Determination

The study aimed to include all eligible MIS-C cases admitted during the specified period, resulting in a census of 209 cases. No formal sample size calculation was performed a priori.

3.6. Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 23. Descriptive statistics summarized clinical and demographic characteristics. Group comparisons were conducted using the chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test) for categorical variables and independent t-tests for continuous variables. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to control for potential confounders. Variables included in the model (e.g., age, sex, comorbidities, ICU admission, inflammatory markers) were selected based on clinical relevance and univariate analysis results (P < 0.20). Results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% CIs. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Missing data were handled using complete case analysis.

3.7. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in adherence to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was ethically approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences (IR.HUMS.REC.1401.382). Informed consent was obtained from the children and their parents.

4. Results

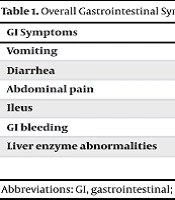

Of the 209 patients included in the study, 56.9% (n = 119) were male and 43.1% (n = 90) were female. The most frequently observed GI symptoms were:

1. Vomiting: 23.0% of all cases (n = 48).

2. Diarrhea: 21.1% (n = 44).

3. Abdominal pain: 9.6% (n = 20).

4. Ileus: 5.7% (n = 12).

5. The GI bleeding: 5.7% (n = 12).

Elevated liver enzymes were noted in 49.3% of the children (n = 103). Subgroup analysis revealed that in multivariable logistic regression, male gender was associated with higher odds of vomiting (aOR = 2.45, 95% CI: 1.35 - 4.44, P = 0.003), and age < 5 years was also associated with vomiting (aOR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.02 - 3.35, P = 0.041). Chi-square analysis revealed that diarrhea was significantly more prevalent in boys (70.5% of all diarrhea cases; P = 0.03). Data stratified by gender and age group are detailed in Tables 1 and 2, which show the proportional distribution of symptoms and laboratory abnormalities among subgroups. The P-values represent the statistical significance of differences between these groups. P-values indicate the statistical significance of differences between subgroups (gender or age).

| GI Symptoms | Percentage (95% CI) | Number of Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Vomiting | 23.0 (17.3 - 29.5) | 48 |

| Diarrhea | 21.1 (15.8 - 27.3) | 44 |

| Abdominal pain | 9.6 (6.0 - 14.5) | 20 |

| Ileus | 5.7 (3.3 - 9.9) | 12 |

| GI bleeding | 5.7 (3.3 - 9.9) | 12 |

| Liver enzyme abnormalities | 49.3 (42.5 - 56.2) | 103 |

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; CI, confidence intervals.

| Symptoms | Prevalence in Subgroup; No. (%) | aOR | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vomiting | ||||

| Boy | 29.4 (35.119) | 2.45 | 1.35 - 4.44 | < 0.01 |

| Girls | 14.4 (13.90) | 1.00 (Ref.) | - | - |

| Age < 5 y | 32.6 (29.89) | 1.85 | 1.02 - 3.35 | < 0.01 |

| Age ≥ 5 y | 15.8 (19.120) | 1.00 (Ref.) | - | - |

| Diarrhea | ||||

| Boy | 26.1 (31.119) | 2.10 | 1.08 - 4.07 | 0.03 |

| Girls | 14.4 (13.90) | 1.00 (Ref.) | - | - |

| Age < 5 y | 24.7 (22.89) | 1.31 | 0.59 - 2.93 | < 0.01 |

| Age ≥ 5 y | 18.3 (22.120) | 1.00 (Ref.) | - | - |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

5. Discussion

This study highlights the significant role of GI symptoms in children diagnosed with MIS-C. The high prevalence of elevated liver enzymes, vomiting, and diarrhea indicates substantial GI system involvement, which influences both diagnosis and management. Our findings align with global research indicating that GI symptoms are a hallmark of MIS-C and can mimic acute surgical conditions like appendicitis (10). Previous studies in Iran have also emphasized that vomiting and abdominal pain are prominent early indicators of MIS-C (11). This study noted a higher prevalence of GI symptoms, particularly vomiting and diarrhea, in boys. This is consistent with other research suggesting that males may experience a more robust inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2, potentially due to differences in hormonal immune regulation and genetic factors (12, 13). Children under five years old showed a significantly higher prevalence of vomiting, likely attributable to their immature immune systems, which may predispose them to a more systemic inflammatory response involving the GI tract (14). Additionally, younger children may have a heightened sensitivity in the gut-brain axis, leading to a lower threshold for vomiting (15). These observations correlate with global studies indicating that younger children often present with more severe GI manifestations (4).

From a clinical perspective, it is essential to recognize GI symptoms as primary manifestations of MIS-C. Children presenting with persistent vomiting, diarrhea, or elevated liver enzymes — especially with a recent history of COVID-19 exposure — should be evaluated for MIS-C. Delayed diagnosis can lead to serious complications, as GI symptoms in MIS-C are frequently accompanied by systemic inflammation affecting the cardiovascular system and other vital organs (16). Distinguishing MIS-C from other conditions with similar symptoms, such as appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease, or gastroenteritis, is critical. This differentiation can be supported by evaluating additional inflammatory biomarkers (e.g., D-dimer, fibrinogen, troponin) and imaging studies. Misdiagnosis can result in inappropriate treatments and delay essential therapies for MIS-C, such as immunomodulators and supportive care (17). The presence of GI symptoms has important implications for treatment and prognosis. Research indicates that children with significant GI involvement often require more intensive care, including hydration therapy, nutritional support, and immunomodulation (18). The high prevalence of elevated liver enzymes in our cohort suggests that routine hepatic monitoring should be integrated into the management protocol for MIS-C.

5.1. Conclusions

The GI symptoms and laboratory abnormalities, particularly elevated liver enzymes, vomiting, and diarrhea, are crucial components of MIS-C. These findings underscore the importance of early detection and tailored interventions, especially for younger children and boys. A multidisciplinary approach to management, including early involvement of pediatric gastroenterologists, is recommended. Public health efforts to increase awareness of MIS-C among healthcare providers and caregivers are essential for improving outcomes.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design relies on the accuracy and completeness of medical records, which may introduce information bias. Second, as a single-center study, the findings may not be fully generalizable to other regions or healthcare settings. The inclusion of only hospitalized cases may also bias the sample toward more severe presentations. Third, the lack of a control group (e.g., children with COVID-19 without MIS-C or with other febrile illnesses) prevents direct comparisons of GI symptom prevalence and severity. Additionally, the absence of standardized symptom severity scores, incomplete COVID-19 vaccination history for all patients, and a lack of long-term follow-up data on GI outcomes are notable limitations. Therefore, the long-term impact of MIS-C on GI health remains unclear. Future multicenter studies with systematic data collection on vaccination status, standardized severity measures, and comorbidity data are needed to better control for these factors.

5.3. Suggestions

Future research should expand to multiple centers to create a broader, more representative dataset. Longitudinal studies are necessary to examine the long-term GI effects in MIS-C survivors. Prospective studies, ideally including control groups and long-term monitoring, are needed to validate these findings and clarify the prognostic significance of GI involvement in MIS-C.