1. Introduction

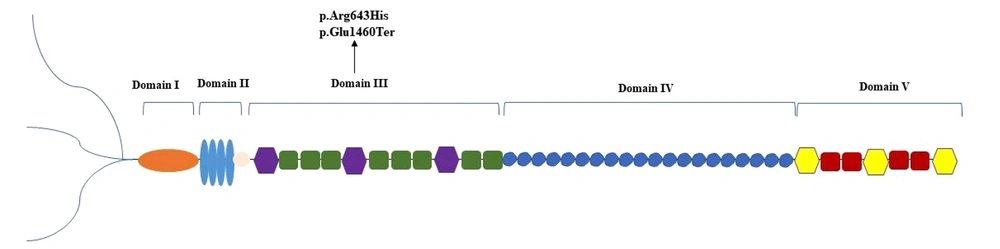

The heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2 (HSPG2) gene, an evolutionarily conserved locus located on chromosome 1p36.1-p35, spans approximately 120 kb. It encodes the large core protein (perlecan) of approximately 467 kDa consisting of 4391 amino acids (1, 2). Structurally, perlecan includes glycosaminoglycan chains attached at its N-terminal end and is organized into five distinct functional domains (I-V) (2, 3). Perlecan, a secreted proteoglycan found within the matrix of various tissues such as cartilage, bone marrow, and skeletal muscle, participates in diverse biological processes, including growth factor binding, angiogenesis, cell adhesion, and maintenance of basement membranes and cartilage (2, 4-6).

Pathogenic variants in the HSPG2 gene are associated with two categories of skeletal disorders: Dyssegmental dysplasia, Silverman-Handmaker type (DDSH; OMIM #224410) and Schwartz-Jampel syndrome type 1 (SJS1; OMIM #255800) (2). The DDSH, a lethal condition in the neonatal period, arises from functional null mutations in the HSPG2 gene, leading to a disturbance in the perlecan secretion into the extracellular matrix. Affected individuals exhibit profound skeletal defects, bowed limbs, short stature, encephalocele, and flattened facial and vertebral malformations (7).

Schwartz–Jampel syndrome type 1 (or chondrodystrophic myotonia) represents a rare genetic disorder with an autosomal recessive (AR) inheritance pattern. This condition is characterized by the presence of skeletal dysplasia and myotonic myopathy, often presenting with a range of phenotypic manifestations such as joint contractures, pigeon breast, reduced stature, and abnormal ear morphology (8, 9). Disease severity correlates with mutation location and residual protein function (2). The SJS1 is classified into two subgroups: SJS1A represents a less severe phenotype, which usually has mutations associated with this phenotype located near the C-terminal region within domains IV and V, and SJS1B (severe manifestation with neonatal onset) (2, 10). Consequently, the diagnosis of SJS1 relies on clinical findings, subsequently requiring molecular validation. The therapeutic intervention of this condition is primarily supportive, focusing on alleviating myotonia (9).

In this case report, we describe an Iranian patient with a novel pathogenic variant in the HSPG2 gene (NM_005529.7: c.1928G>A; p.Arg643His, c.4378G>T; p.Glu1460Ter) identified through whole-exome sequencing (WES) and consistent with SJS1. This finding extends the mutational spectrum and advances our knowledge of genotype-phenotype correlation in HSPG2-related disorders. Unlike previously reported mutations, this compound heterozygous variant includes a novel missense mutation and a nonsense mutation. This offers new insight into SJS1 heterogeneity and highlights the importance of expanding the variant database.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. Clinical Examination

We report a 13-year-old Iranian male of Baloch ethnicity, born to consanguineous parents, who was referred to our clinical center for evaluation of progressive muscle weakness. He was delivered at full term via spontaneous vaginal delivery, with normal birth weight, length, and head circumference. Perinatal history was unremarkable, with no reported complications during pregnancy or delivery.

A detailed family history revealed several relatives with comparable musculoskeletal abnormalities, raising a strong suspicion of an inherited disorder. From early infancy, the patient demonstrated bilateral congenital hip dislocation, presumed to be secondary to abnormal fetal hip joint development. Surgical interventions were attempted in early childhood, but residual joint instability persisted.

On the current physical examination, the patient presented with fixed flexion contractures of the fingers, particularly involving the proximal interphalangeal joints, as well as other skeletal abnormalities, including limb deformities and abnormal spinal curvature. The muscular examination revealed generalized hypotonia and reduced muscle strength, more pronounced in the lower limbs.

An ophthalmologic evaluation identified bilateral cataracts and high-grade myopia necessitating corrective lenses. Additional systemic examination did not reveal cardiopulmonary or gastrointestinal involvement. The combination of skeletal deformities, joint contractures, and ocular abnormalities, along with the consanguineous family background, was highly suggestive of a rare hereditary skeletal dysplasia, prompting molecular genetic testing for a definitive diagnosis.

2.2. Molecular Investigations

Based on the clinical presentation, SJS1 was suspected. Following a detailed clinical assessment, genetic counseling was provided to the proband and his family to facilitate diagnostic confirmation. Written informed consent was obtained from the legal guardian of the patient before genetic testing. Peripheral blood samples were collected from the proband and his parent in EDTA-anticoagulated tubes, and genomic DNA was extracted.

The WES was conducted on genomic DNA extracted from the proband's whole blood, with sequencing services. Bioinformatic analysis included raw data quality control using FastQC (Babraham Institute, UK), adaptor trimming with Trimmomatic (USA), alignment to the reference human genome (GRCh37/hg19) using BWA-MEM (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner), and variant calling using SAMtools and GATK HaplotypeCaller (Broad Institute, USA).

The WES revealed a compound heterozygous variant (NM_005529.7: c.1928G>A; p. Arg643His, c.4378G>T; p. Glu1460Ter) in the HSPG2 gene, confirming the diagnosis (Table 1). The pathogenicity of these variants was examined using prediction tools (e.g., Mutation Taster, SIFT, and PolyPhen), which supported the deleterious effect of these variants. In silico analysis using the Mutalyzer 3 database was also conducted. No further clinically relevant variants related to the patient's phenotype were detected in the WES data.

| Gene; Genomic Position | cDNA Position | Protein Change | Genomead Frequency | Iranome Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSPG2 | ||||

| chr1:21880726 (GRCh38) | NM_005529.7 c.1928G>A | NP_005520.4 p.Arg643His | < 0.001 | 0.009901 |

| chr1:21865302 (GRCh38) | NM_005529.7 c.4378G>T | NP_005520.4 p.Glu1460Ter | < 0.001 | Not found |

3. Discussion

The SJS1 is a rare AR disorder caused by pathogenic mutations in HSPG2, the gene encoding perlecan (7). This protein plays a multifaceted role in biological processes such as mediating growth factor interactions, angiogenesis, cell adhesion, and maintenance of basement membranes and cartilage (2, 6). Therefore, pathogenic variants in this gene that compromise the synthesis or secretion of perlecan can cause multisystem disorders such as SJS1 and DDSH (7). The clinical hallmarks of SJS1 include myotonia, chondrodysplasia, joint contractures, and craniofacial dysmorphism (8).

So far, over forty distinct HSPG2 variants have been published in SJS1 patients (11). According to the documented variant mapping, the majority of these variants are located in domain IV, followed by domains III, II, V, and I, respectively (9). Since these domains mediate various biological functions, such as growth factor binding (domain I), stabilizing basement membranes (domain III), and interacting with extracellular ligands (domain IV), changes in different domains may result in different clinical outcomes (2).

Clinical data from reported cases showed myotonic symptoms in all patients, along with typical facial features due to skeletal dysplasia (9). In 2013, Bauche et al. described the first case with a compound heterozygous mutation involving domains I and III. This patient experienced spontaneous improvement in muscle symptoms (12). After that, Brugnoni et al. reported the second case of spontaneous improvement in muscle signs, with mutations located in domains III and V (9). Our patient has compound heterozygous variants located in domain III of the perlecan protein (Figure 1). Despite the similarity in domain involvement with previously reported cases, our patient did not show any spontaneous improvement in symptoms. This difference may reflect the particular nature of his variants. The truncating mutation could eliminate important downstream domains, while the missense substitution may lead to local misfolding or protein instability. The instability could prevent functional compensation that might otherwise occur. This finding may indicate that the identified variants have a more destructive impact on functional performance or that specific amino acid substitutions and truncations lead to protein misfolding or degradation.

One of the identified variants in our patient (c.4378G>T) results in a premature stop codon, which causes the early truncation of the protein and loss of the following domains. Another variant is a missense mutation (c.1928G>A) with a very low allele frequency in the Iranome database. It is specifically absent in the homozygous state and present at a heterozygous frequency of 0.0198 among 202 healthy individuals from the Balouch ethnic group, which matches the patient's ethnicity. Only two individuals in this population were heterozygous carriers, supporting the rare nature of the variant and its potential pathogenicity. Additionally, multiple prediction tools supported the deleterious effect of these variants: SIFT predicted this variant as “deleterious”, PolyPhen rated it as “probably damaging”, and MutationTaster marked this variant as disease-causing. These tools combine evolutionary conservation, biochemical properties, and known variant databases to determine functional impact. However, careful interpretation is needed along with clinical and population data. The coexistence of this missense variant with a second pathogenic truncating variant in a compound heterozygous state likely explains the disease phenotype in our patient.

3.1. Conclusions

We reported a 13-year-old Iranian patient of Balouch ethnicity with novel compound heterozygous mutations in HSPG2 (NM_005529.7: c.1928G>A; p. Arg643His, c.4378G>T; p. Glu1460Ter) associated with the SJS1 phenotype. This phenotype includes skeletal deformities, finger contractures, muscle weakness, and ocular involvement. Our findings expand the mutational spectrum of HSPG2-related disorders and offer new insights into genotype-phenotype correlations, especially within the Balouch population. While our study has a single-patient design and lacks functional tests, it highlights the significant value of combining WES with thorough clinical and population-based analyses to identify rare diseases and improve accuracy in genetic diagnosis and counseling for timely and personalized care. Furthermore, this underscores the importance of mutation-level analysis in predicting disease progression and guiding patient care.