1. Background

Obesity has emerged as a critical public health concern, with its prevalence steadily increasing worldwide. It is associated with numerous metabolic disorders, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and certain cancers (1). The World Health Organization reports that approximately 1.9 billion adults were classified as overweight in 2016, with over 650 million of these individuals being obese (2). This alarming trend underscores the urgent need for effective interventions to combat obesity and its associated health risks.

Physical inactivity is a significant contributor to the obesity epidemic, with a substantial portion of the global population failing to meet recommended levels of physical activity (3). The lack of regular exercise not only exacerbates weight gain but also negatively impacts metabolic health. Recent studies have highlighted the potential of exercise to modulate microRNA (miRNA) levels, which play a pivotal role in regulating various biological processes, including lipid metabolism and inflammation (4). Specifically, miRNAs such as miRNA-192a and miRNA-122 have been implicated in the regulation of lipid profiles, making them important targets for understanding the metabolic effects of exercise (5, 6).

Resistance training (RT) and aerobic exercises are two prominent forms of physical activity that have been shown to influence metabolic health differently. The RT primarily focuses on muscle strength and mass, while aerobic exercises emphasize cardiovascular endurance. Both types of exercise have demonstrated beneficial effects on body composition and metabolic parameters, yet their specific impacts on lipid profiles and miRNA levels remain inadequately explored (7, 8).

2. Objectives

This study aims to compare the effects of RT and combined training (COT) on lipid profiles and the levels of miRNA-192a and miRNA-122 in women with overweight/obesity. By identifying the differential impacts of these exercise modalities, the research seeks to contribute to the development of tailored exercise interventions that effectively address obesity and its associated metabolic disturbances. The findings from this study could inform public health strategies aimed at improving quality of life and reducing healthcare costs associated with obesity.

3. Methods

In this quasi-experimental study, 24 women with overweight/obesity, aged between 20 and 45 years, were recruited from local community centers and fitness facilities through convenience sampling. We included women with a Body Mass Index (BMI) ranging from 25 - 29.5 kg/m2 (overweight) and 30 - 40 kg/m2 (obesity). Participants were required to have no history of chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease or diabetes, which could interfere with their ability to exercise. Additionally, they were not engaged in regular physical activity, defined as less than 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week for at least six months prior to the study.

Participants were excluded from the study if they were pregnant or breastfeeding, had undergone recent surgery or sustained an injury that could impact their physical activity, or were currently taking medications that affect metabolism or weight, such as steroids or weight loss drugs. Additionally, any condition that contraindicated exercise participation according to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines also served as a basis for exclusion.

Participants were randomly assigned to two groups, each consisting of 15 individuals. Due to excessive absenteeism, three participants from the COT group and four from the RT group were excluded. Consequently, the final analysis included data from 12 participants in the COT group and 11 participants in the RT group. Both groups underwent an 8-week exercise program consisting of three sessions per week. Subjects were initially required to complete the general Health and Wellness Questionnaire and provide written informed consent to confirm their voluntary participation in the study. This research received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Isfahan under license number IR.UI.REC.1403.029, in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

Individuals classified as inactive were those who had not engaged in any regular training over the past year. One week prior to the commencement of the study, variables such as weight, body fat percentage, and maximal oxygen consumption were assessed in the subjects. The initial blood sample was collected within 48 hours before the first training session, while the second sample was obtained 48 hours after the final training session. Anthropometric measurements, cardiovascular and muscular fitness, levels of miRNAs, and levels of fasting blood sugar (FBS) and lipid profile were evaluated before and after training sessions.

3.1. Training Protocols

The training protocols were developed by the researchers, drawing on insights from previous investigations, and participants underwent two training protocols as follows.

3.1.1. Resistance Training

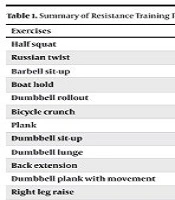

This group engaged in a structured RT program focusing on major muscle groups, which included exercises such as squats, bench presses, and deadlifts. The training intensity was progressively increased to ensure optimal overload and adaptation (Table 1) (9).

| Exercises | Time/Repetitions | Number of Sets | Rest Time After Each Set (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Half squat | 25 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Russian twist | 25 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Barbell sit-up | 30 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Boat hold | 15 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Dumbbell rollout | 10 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Bicycle crunch | 25 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Plank | 40 s | 3 | 30 |

| Dumbbell sit-up | 15 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Dumbbell lunge | 15 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Back extension | 30 s | 3 | 30 |

| Dumbbell plank with movement | 10 rep/leg | 3 | 30 |

| Right leg raise | 25 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Left leg raise | 25 rep | 3 | 30 |

| Side plank | 20 s on each side | 3 | 30 |

Abbreviation: Rep, repetition.

a Before starting the exercises, a warm-up of 5 minutes including dynamic and stretching movements is recommended.

b At the end of the workout, a 5-minute cool-down with stretching movements is suggested.

c To increase the training load, every two weeks, and 5 movements were added to the number of repetitions and 5 seconds to the duration of each movement. The exercises were organized in a circuit format, alternating between upper and lower body.

3.1.2. Combined Training

Participants in this group participated in a combination of resistance exercises and aerobic activities. The circuit training incorporated both strength and cardio components, aiming to enhance cardiovascular fitness while promoting muscle strength. In the COT protocol, which involved both RT and interval aerobic training (AT), RT was executed first after the body was warmed up. After a rest interval of 10 to 15 minutes, aerobic interval training was conducted following the specified protocol (Tables 2 and 3) (10).

| Exercises | Number of Sets | Time/Repetitions |

|---|---|---|

| Crunch | 2 | 10 rep |

| Russian twist with dumbbell | 2 | 10 rep |

| Bicycle crunch | 2 | 20 rep |

| Plank | 2 | 20 rep |

| Dumbbell sit-up | 2 | 10 rep |

| Right leg raise | 2 | 10 rep |

| Left leg raise | 2 | 10 rep |

| Side plank | 2 | 15 s on each side |

Abbreviation: Rep, repetition.

a In the combined training (COT) section, which involved both resistance and interval aerobic training (AT), resistance training (RT) was executed first after the body was warmed up.

b Before starting the exercises, a warm-up of 10 - 15 minutes including dynamic and stretching movements is recommended.

c At the end of the workout, a 5-minute cool-down with stretching and light movements is suggested.

d To increase the training load, every two weeks, and 5 movements were added to the number of repetitions and 5 seconds to the duration of each movement. The exercises were organized in a circuit format, alternating between upper and lower body.

| Variables | Weeks 1 and 2 | Weeks 3 and 4 | Weeks 5 and 6 | Weeks 7 and 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise intensity (%HR max) | 55 - 60 | 60 - 65 | 65 - 70 | 70 - 75 |

| Number of exercise sessions | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| Duration of each exercise interval (s) | 60 - 70 | 70 - 80 | 80 - 90 | 90 - 120 |

| Duration of exercise per session (min) | 6 - 7 | 8 - 10 | 10 - 15 | 15 - 20 |

| Exercise method | Running | Running | Running | Running |

| Rest intensity (%HR max) | 50 - 60 | 50 - 60 | 50 - 60 | 50 - 60 |

| Number of rest periods | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 |

| Duration of each rest interval (s) | 60 - 75 | 75 - 90 | 90 - 120 | 90 - 120 |

| Duration of rest per session (min) | 6 - 7 | 8 - 10 | 15 - 20 | 20 - 25 |

| Total duration of each session (min) | 12 - 15 | 16 - 20 | 25 - 35 | 35 - 45 |

a After a rest interval of 10 to 15 minutes, aerobic interval training was conducted following the specified protocol.

3.2. Laboratory Measurements

The miRNA-122 and miRNA-192a levels were extracted using a standardized protocol involving isolation kits designed for serum samples. Quantification was performed using real-time PCR, following established methodologies for miRNA analysis (11).

3.2.1. Fasting Blood Glucose and Lipid Profile

Fasting blood samples were obtained after a 12-hour overnight fast to measure glucose and lipid profiles using the ELISA method.

3.3. Anthropometric Measurements

Anthropometric assessments were conducted at baseline and post-intervention using standardized procedures:

- Body weight: Measured using a calibrated digital scale to the nearest 0.1 kg.

- Height: Measured using a stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm.

- The BMI: Calculated using the formula BMI = weight (kg)/height (m)2 (12).

The evaluation of body fat percentage was performed indirectly utilizing a four-compartment skinfold thickness equation, as described by Eston and Reilly (12): %Fat = 22.18945 + (age × 0.06368) + (BMI × 0.60404) - (Ht × 0.14520) + (∑42 × 0.30919) - (∑42 × 0.00099562); where Ht is in cm and ∑4 is the sum of skinfolds as specified (Table 4).

| Variables | COT Group (N = 12) | RT Group (N = 11) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 31.91 ± 6.18 | 28.16 ± 7.52 | 0.260 |

| Weight (kg) | 75.75 ± 10.98 | 77.16 ± 7.39 | 0.519 |

| Height (cm) | 160.8 ± 5.25 | 157.4 ± 6.1 | 0.992 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3 ± 3.44 | 31.2 ± 3.331 | 0.918 |

| Body fat percentage | 41.5 ± 2.44 | 43.4 ± 2.89 | 0.396 |

Abbreviations: COT, combined training; RT, resistance training; BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

3.4. Cardiorespiratory and Muscular Fitness Assessments

3.4.1. Cardiorespiratory Fitness

The cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) was measured by a multistage 20-m shuttle run test (20-m SRT). The 20-m SRT is widely used to test cardiorespiratory fitness and has been validated as a reliable predictor of maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) (13). The VO2max was determined through the application of the equation derived from earlier studies (13): VO2max (mL/kg/min) = 41.76799 + (0.49261 × laps) - (0.00290 × laps2) - (0.61613 × BMI) + (0.34787 × sex × age); where sex is 1 if male or 0 if female, and age is in years.

3.5. Muscle Strength and Endurance

3.5.1. Muscular Endurance

Muscular endurance among participants was assessed through a push-up test, with female participants performing knee push-ups. The total number of push-ups completed was documented (9).

3.5.2. Hand Grip Strength

Hand grip strength was assessed using an adjustable spring hand dynamometer (SAEHAN, made in South Korea), which has a resolution of 0.5 kg. Each participant performed three trials with their dominant hand, allowing for 60 seconds of rest between each measurement. The highest value obtained was documented (14).

3.5.3. Abdominal Muscular Endurance

The assessment of participants' muscular endurance in the abdominal area was conducted through a sit-up test. The total number of sit-ups performed was documented (Table 5) (14).

| Measured Variables | COT Group | P-Value Within Group | RT Group | Within Group P-Value | Between Groups P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | ||||

| Weight (kg) | 75.8 ± 10.9 | 72.4 ± 10.5 | 0.001 | 77.2 ± 7.4 | 74.7 ± 7.2 | 0.001 | 0.068 |

| BMI (kg.m2) | 29.3 ± 3.4 | 28.0 ± 3.5 | 0.001 | 31.2 ± 3.3 | 30.2 ± 3.29 | 0.001 | 0.142 |

| WHR | 0.970 ± 0.03 | 0.9 ± 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.19 |

| Body fat percentage | 41.5 ± 2.4 | 40.0 ± 2.6 | 0.001 | 43.4 ± 2.9 | 42.3 ± 2.9 | 0.001 | 0.024 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||||||

| miR-192a (fold change) | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 0.032 | 3.86 ± 1.1 | 4.08 ± 0.9 | 0.145 | 0.879 |

| miR-122 (fold change) | 2.51 ± 1.3 | 1.59 ± 1.0 | 0.002 | 2.89 ± 1.3 | 1.87 ± 1.5 | 0.001 | 0.871 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 48.6 ± 10.2 | 58.91 ± 8.3 | 0.020 | 40.0 ± 10.0 | 49.33 ± 5.4 | 0.003 | 0.014 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 89.75 ± 21.3 | 81.7 ± 21.9 | 0.113 | 111.16 ± 25.6 | 110.25 ± 24.7 | 0.094 | 0.069 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 185.9 ± 38.8 | 163.3 ± 23.9 | 0.024 | 180.4 ± 33.4 | 175.3 ± 37.5 | 0.110 | 0.297 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 158.9 ± 11.2 | 127.83 ± 75.1 | 0.120 | 148.08 ± 59.7 | 116.00 ± 42.2 | 0.070 | 0.711 |

| Blood sugar (mg/dL) | 96.50 ± 15.5 | 89.50 ± 10.6 | 0.047 | 91.25 ± 10.9 | 85.83 ± 7.9 | 0.111 | 0.647 |

| Muscular and cardiorespiratory fitness | |||||||

| Hand-grip strength (kg) | 27.66 ± 4.6 | 31.83 ± 4.4 | 0.001 | 26.83 ± 4.9 | 31.75 ± 5.3 | 0.001 | 0.474 |

| Sit-up (count) | 8.8 ± 1.4 | 25.3 ± 5.9 | 0.001 | 11.2 ± 3.1 | 22.1 ± 3.1 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Push-up (count) | 7.3 ± 1.9 | 17.3 ± 3.8 | 0.001 | 6.8 ± 1.3 | 13.3 ± 1.6 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| VO2max (mL.kg-1.min-1) | 27.6 ± 1.7 | 28.94 ± 1.6 | 0.001 | 26.96 ± 1.3 | 28.4 ± 1.5 | 0.001 | 0.42 |

Abbreviations: COT, combined training; RT, resistance training; BMI, Body Mass Index; VO2max, maximum volume of oxygen consumption.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software version 21 (IBM, New York, USA). Descriptive statistics were employed to calculate the mean and standard deviation for the measured variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized to assess the normality of the data. Paired t-tests were used for within-group comparisons, and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used for between-group comparisons. A significance level of P ≤ 0.05 was established for hypothesis testing.

4. Results

In this study, 24 women classified as overweight or obese participated in two specifically chosen COT and RT programs. The baseline characteristics of the participants in both groups are presented in Table 1. The findings related to anthropometric measurements, biochemical results, and muscle strength and endurance in both groups before and after the exercises are presented in Table 2.

Within-group analysis indicated a significant increase in physical strength and endurance, along with a reduction in weight, BMI, and fat percentages in both training groups (P < 0.05). Regarding biochemical measurements, there was a significant decrease in miR-122 levels after training in both groups (P < 0.05). In the COT group, the level of miR-192a increased significantly after training (P = 0.03).

The ANCOVA analysis indicates that the training programs have a statistically significant effect on HDL cholesterol levels (P < 0.05) and body fat percentage (P < 0.05), with corresponding F-values suggesting a strong effect size. The results for push-up and sit-up performance also reached statistical significance (P < 0.01), indicating a robust impact of the training interventions on muscular endurance.

While the P-values for weight (P = 0.06) and LDL cholesterol levels (P = 0.068) are slightly above the conventional threshold of P ≥ 0.05, they indicate trends that may be clinically relevant and suggest the potential for significance with a larger sample size or adjusted study design. The F-values associated with these outcomes further suggest that the training programs account for a considerable proportion of the variance observed in the dependent variables.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to compare the effects of two exercise training methods — RT and a combination of resistance plus AT — on lipid profiles and levels of miRNA-192a and miRNA-122 in women with overweight/obesity. Our findings demonstrated that although participants in both groups experienced a statistically significant reduction in weight, BMI, and body fat percentage, as well as improvements in all variables related to physical strength, women in the COT group had a significantly lower body fat percentage, better sit-up and push-up improvement, and marginally significant lower weight than the RT group.

Furthermore, the COT group exhibited a significant increase in miR-192a levels, HDL levels, and a decrease in miR-122 levels, cholesterol, and blood glucose levels. In contrast, women in the resistance group had a significant decrease in miR-122 levels and an increase in HDL levels. Although both groups had a significant increase in HDL levels, the level of HDL was significantly higher in the COT group.

These results highlight the differential impacts of exercise modalities on metabolic markers and miRNA levels, suggesting that COT may offer superior benefits for body composition, specific miRNA regulation, and lipid levels, especially HDL and LDL.

Studying miRNA levels is vital for understanding the regulatory networks that control gene expression and metabolism. Their role in modulating gene expression makes them important biomarkers for diseases, particularly metabolic disorders like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (15, 16). By elucidating how different exercise modalities influence these miRNAs, this study contributes valuable insights into potential therapeutic strategies for obesity-related metabolic disorders. Such investigations are crucial for developing targeted interventions that can improve health outcomes and enhance the quality of life for individuals struggling with excess weight. Analyzing miRNA levels helps researchers uncover the molecular mechanisms behind these conditions and identify potential therapeutic targets (17).

This research focuses on two specific miRNAs: MiR-192a and miR-122, which are particularly relevant to lipid metabolism and obesity (18, 19). MiR-192a regulates lipid homeostasis and glucose metabolism, playing a crucial role in responses to exercise and dietary changes. Its increase following COT suggests a potential role in enhancing metabolic health and reducing fat accumulation (20). Some previous studies revealed that elevated miR-122 levels are linked to increased lipid accumulation and hepatic steatosis, making it an important biomarker for liver health (21, 22). Interventions that lower miR-122 levels have shown promise in improving lipid profiles and insulin sensitivity, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target for obesity-related complications (23).

Beyond lipid metabolism, miR-122 is also involved in regulating inflammation and oxidative stress, which are often elevated in obesity. Exercise has been shown to mitigate inflammation and improve metabolic health, potentially through the modulation of miRNA expression (24, 25).

Aerobic exercise has been shown to significantly influence miRNA levels, particularly miR-192a, in the context of obesity and metabolic health. Research in obese mice indicates that AT alters the circulating profile of extracellular vesicle (EV) miRNAs, leading to decreases in miR-122 and miR-192 levels, which are associated with improved adipose tissue metabolism and reduced adipocyte hypertrophy (26, 27). Some studies indicate that elevated levels of miR-192a are linked to prediabetes and diabetes, with exercise training potentially contributing to its down-regulation. Notably, in these studies, the subjects' diets were predominantly controlled, and the intensity and duration of exercise varied. Consequently, it can be concluded that the expression patterns of miR-192a may vary under different conditions, suggesting that further research is necessary to explore the impact of exercise training, considering the intensity, duration, and type of exercise involved.

In this instance, it is essential to interpret and compare conclusions drawn from findings in animal models with caution. This is due to the fact that the intensity, duration, and type of training may differ between human and non-human species, making the responses and adaptations resulting from various training sessions non-comparable. Furthermore, comprehending the dynamics of these miRNAs can yield significant insights for creating targeted strategies aimed at enhancing metabolic health and preventing complications associated with obesity (28).

Our findings support previous research indicating that COT is more effective for improving body composition and metabolic health than RT alone (29, 30). Amare et al. found that inactive males participating in COT, RT, and AT all showed significant reductions in body fat percentage and cholesterol, with CT and AT being particularly effective (29). In the Cardio RACE trial, Lee et al. studied 160 obese older adults and found that the COT group had the most significant reductions in intramuscular (41%) and visceral adipose tissue (36%) and the greatest improvement in insulin sensitivity (86%) (30). Additionally, studies on aerobic exercise intensity showed that moderate-intensity combined with RT is effective for managing obesity in middle-aged women, potentially offering greater benefits than vigorous intensity (31, 32). Overall, the synergistic effects of aerobic and RT are crucial for optimal metabolic outcomes.

In summary, although animal studies have yielded encouraging results, there is a scarcity of human research that specifically investigates the impact of exercise on miR-192a, miR-122, and their association with obesity. Our study aims to address this gap by comparing the effects of resistance and COT on miR-192a and miR-122 levels and lipid profiles in women with obesity. The significant increase in miR-192a levels in the COT group suggests a potential role for this miRNA in mediating the beneficial effects of exercise on lipid metabolism. Conversely, the decrease in miR-122 levels across both training groups may indicate enhanced lipid metabolism and reduced hepatic fat accumulation, which are critical for mitigating the risks associated with obesity. These findings underscore the importance of miRNAs as biomarkers for assessing the impact of exercise interventions on metabolic health. By demonstrating how different training modalities influence miRNA levels, this study highlights the potential for utilizing miRNAs as targets for future therapeutic strategies aimed at improving metabolic outcomes in overweight and obese individuals.

However, some limitations exist, such as the relatively small sample size and the lack of a control group, which limits the ability to attribute changes solely to the exercise interventions and may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Furthermore, the short duration of the intervention may not capture long-term adaptations. Future research should consider larger sample sizes and longer intervention periods to confirm the findings and explore the long-term effects of different exercise modalities on miRNA levels and metabolic health.