1. Introduction

Periodontitis is a progressive inflammatory disease affecting the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone, leading to irreversible tissue destruction and tooth loss (1). The disease is primarily caused by bacterial biofilms, including Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and the red complex bacteria (Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, Treponema denticola) (2). Diagnosis is based on clinical attachment loss, indicating permanent tissue damage (3). Scaling and root planing (SRP) is a standard non-surgical treatment, but its efficacy is limited due to bacterial persistence, necessitating antimicrobial adjuncts such as chlorhexidine (2). However, chlorhexidine has side effects, including tooth staining and taste alterations (4).

Probiotic therapy, particularly with Lactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus salivarius, and Bifidobacterium species, offers an alternative by modulating immune function and inhibiting pathogens (5-7). This study evaluates L. salivarius NK02 mouthwash against chlorhexidine to determine its effectiveness in managing mild to moderate chronic periodontitis.

The primary root cause of periodontitis is a complex interplay between microbial dysbiosis and immune-response dysfunction. Medical therapies involving SRP have demonstrated effectiveness in lowering microbial levels while enhancing treatment outcomes. Periodontal pathogens require more than mechanical therapy for complete removal, leading to the need for antimicrobial agents and probiotics in treating these diseases.

Probiotic therapy has emerged as a new therapeutic approach in recent years to conventional periodontal treatment, offering three main benefits: microbiome alteration control, immune system enhancement, and inflammation reduction. A comprehensive review of modern research (from 2022 onward) on utilizing probiotics in periodontal disease treatment has evaluated their performance, mechanisms, and practical effects.

The review and analysis by Hardan et al. (8) evaluated how probiotics work as adjunctive therapy for patients with periodontitis. Data from 21 clinical trials established that patients treated with probiotics in combination with SRP showed improved PPD and clinical attachment level (CAL) results, as well as better bleeding on probing (BOP) measurements. Studies found that probiotics did not significantly affect Plaque Index or its removal, since their main function pertained to inflammation regulation.

Research conducted by de Brito Avelino et al. (9) exclusively studied how probiotics benefit diabetic individuals who have periodontal disease. The research evaluated the effects of probiotics on periodontal parameters and glycemic measures, as diabetes is an established risk for periodontitis. Clinical measurements of periodontal health displayed better results after probiotic treatment, as BOP scores decreased along with PPD measurements, and probiotics modulated inflammatory markers such as IL-8, IL-10, and TNF-α. The research did not establish sufficient proof that probiotics reduce glycated hemoglobin levels, although more work is needed regarding their influence on systemic metabolic operations.

Jaffar and Jalaluddin (10) provided a meta-analysis about how probiotics affect proinflammatory cytokines during periodontal disease progression. Research data indicated that probiotics affect inflammatory responses through modified levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, but these findings remained inconclusive due to small sample sizes and methodological differences across studies. There is a need for larger clinical trials with proper designs to establish firm medical findings.

The findings from Puzhankara et al. (11) in their systematic review established that probiotics demonstrated better outcomes than antibiotics for PPD and CAL measurements during periodontal therapy. Antibiotics offered better results for both Plaque Index and Gingival Index. The research shows that combining antibiotics with probiotics delivers the most powerful outcomes, suggesting that probiotics should be used as supplementary rather than single therapy.

An evidence-based study documented by Reddy et al. (12) studied the clinical and microbiological effects of probiotic supplements on individuals with periodontitis. The research data showed that the probiotic group experienced greater improvements in probing depth, CAL, and BOP measurements compared to the placebo group. Analysis of the subgingival microbiome showed periodontal pathogen reduction along with increased beneficial bacterial counts, demonstrating how probiotics regulate the microbial community.

Salinas-Azuceno et al. (13) conducted research on using L. reuteri Prodentis as a single therapy during periodontitis treatment. Research findings showed that periodontal inflammation levels reduced along with microbial imbalances during a three-month observation period, but the combination of probiotics with SRP achieved better outcomes. The complete therapeutic effects of probiotics become evident when patients receive complementary periodontal therapies.

Research standardized by Li et al. (14) evaluated how combining probiotics with SRP affects patients with chronic periodontitis. The data showed that taking probiotics resulted in substantial and statistically significant improvements in all monitored periodontal parameters, including Plaque Index, probing depth, CAL, Gingival Index, and BOP. The studies confirmed that probiotic interventions helped decrease subgingival pathogen quantities, thus supporting their role in maintaining the microbiome and securing periodontal tissues.

Ghazal et al. (15) performed a placebo-controlled clinical trial that analyzed antibiotic and probiotic treatments added to SRP for periodontitis treatment in smokers. Testing revealed that both treatments brought better outcomes to periodontal measurements, yet produced identical statistical outcomes between the studied groups. The evidence indicates that probiotics have potential as an antibiotic replacement option considering the growing antibiotic resistance problem.

Butera et al. (16) conducted research to evaluate how effective probiotics are when used with non-surgical periodontal therapy for the long term. According to the research, the use of probiotics showed better short-term clinical outcomes, yet failed to establish definitive long-term results that extended past the three-month period. The success of probiotic therapies requires additional studies to determine the best treatment period and proper administration protocols.

Users can find beneficial information about the employment of probiotics and kefir in initial periodontal therapy from the clinical trial conducted by Sahin et al. (17). Subjects who received probiotic supplements along with consuming kefir showed a combined effect of improving periodontal measurements alongside substantial decreases in T. forsythia counts. The research demonstrates that taking probiotics, either as supplements or present in probiotic-rich food items, helps improve gum health.

Recent studies demonstrate that probiotics show great potential for treating periodontal diseases in patients. Professional medical studies show that administering probiotics leads to better periodontal clinical measurements, adjusts inflammatory processes, and changes oral bacterial communities in the gums. The supportive nature of probiotic therapy as an additional treatment approach is established, but researchers still need to determine the most effective strains, treatment amounts, and lengths. Relevant research demands investigation into how probiotics affect long-term results, as well as standardized treatment procedures and personalized patient reactions to probiotic interventions. Therefore, the present randomized triple-blind clinical trial aimed to compare the clinical efficacy of a Lactobacillus salivarius NK02 probiotic mouthwash with chlorhexidine and placebo as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in patients with mild to moderate chronic periodontitis.

2. Materials and Methods

A randomized triple-blind clinical trial was conducted to assess the effectiveness of probiotic mouthwash compared to chlorhexidine and placebo in patients with chronic periodontitis, regarding their clinical periodontal outcomes.

The Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences provided research approval for the project, and the clinical trial received formal registration before project initiation. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (IR.ZAUMS.REC.1398.371). The trial was prospectively registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20191002044957N1). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Based on the Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Trials (chapter 1), the following codes were observed in this study: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 18. According to the Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Trials (chapter 2), the following codes were observed: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12. Based on the Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Trials (chapter 3), the following codes were observed: 1 and 2. All participants signed a written consent document prior to starting their involvement in the study.

The research, conducted at the Periodontology Department of the Dental School, enrolled 42 patient referrals between 2019 and 2020. The researchers adopted a selection approach that followed pre-established criteria to choose patients for the study.

Participants were randomly allocated into one of three groups (probiotic, chlorhexidine, and placebo) with a 1:1:1 ratio using a computer-generated random number sequence (https://www.random.org). The allocation sequence was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE). The envelopes were prepared by an independent staff member not involved in the study. This study was triple-blinded: Tthe participants, the dental student who performed all clinical examinations and interventions, and the statistician who analyzed the data were all blinded to the group assignments. The mouthwashes were prepared in identical containers labeled only with the participant's code by a third party not involved in the trial. Inclusion criteria:

1. Age over 18 years.

2. Presence of moderate to severe chronic periodontitis.

3. Probing pocket depth (PPD) between 3–7 mm.

4. Voluntary participation and written informed consent.

5. General systemic health.

6. Presence of at least 20 teeth.

7. Absence of systemic diseases, including immunodeficiency disorders and lactose intolerance.

8. Absence of xerostomia.

9. No use of medications affecting salivary flow.

10. No antibiotic use in the past three months.

11. No immunosuppressive drug use in the past six months.

12. Non-smokers.

13. Non-pregnant and non-lactating women.

14. No use of probiotic products.

15. No periodontal treatment in the past six months.

The study excluded participants who did not follow the research protocol or who discontinued participation.

The sample size was calculated based on a previous study by Vivekananda et al. (18), expecting a mean difference in PPD of 0.5 mm with a standard deviation of 0.5 mm. Using α = 0.05 and β = 0.20 (power = 80%), a minimum of 14 participants per group (42 total) was required. Consecutive eligible patients were recruited from the clinic and then randomly allocated into the three study groups using a computer-generated random sequence and SNOSE allocation concealment.

Participants were assigned to one of three intervention groups based on random procedures:

- Probiotic Mouthwash group: Lactobacillus salivarius NK02-based mouthwash.

- Chlorhexidine Mouthwash group: 0.2% chlorhexidine solution.

- Placebo group: Normal saline mouthwash.

The study investigators used equivalent-looking mouthwash containers and identification codes to preserve the triple-blind status. The principal investigator kept the study codes confidential, and they were inaccessible to patients, the dentistry students administering treatments, and the statistician.

At baseline (probing 1), patients underwent a complete periodontal examination performed by a dental student under the supervision of a periodontology professor. The periodontal charting was recorded using a Williams probe, documenting parameters such as PPD, Modified Gingival Index (MGI), and BOP.

Probiotic mouthwash: The L. salivarius NK02 mouthwash contained 1 × 108 CFU/mL, suspended in a phosphate-buffered saline vehicle with mint flavoring (manufacturer: Zist Takhmir Company, Iran). Viability was confirmed throughout the study period.

Chlorhexidine and placebo: The 0.2% chlorhexidine and normal saline placebo were matched in color, taste, and packaging. All mouthwashes were dispensed in identical opaque bottles labeled only with participant codes to maintain blinding.

To standardize oral hygiene, all participants were provided with identical oral hygiene kits, including a soft-bristle toothbrush, toothpaste, and dental floss. They were instructed on the Bass toothbrushing technique and proper flossing methods. Patients were instructed to brush three times daily (morning, noon, and night) and floss once daily in the evening. They were advised to refrain from using any other oral hygiene products during the study. The pre-specified primary outcome was the change in PPD at 1 and 3 months. Secondary outcomes were changes in MGI and BOP percentage.

Following the baseline examination, all participants underwent professional SRP along with prophylaxis using a non-oil-based polishing paste. They were then provided with the assigned mouthwash. Participants were instructed to rinse with 10 mL of the mouthwash twice daily for one minute, 30 minutes after brushing, for one month. Proper use of the mouthwash was demonstrated to each participant, and written instructions were also provided. Follow-up periodontal evaluations were conducted at one month (probing 2) and three months (probing 3) post-treatment. At each visit, PPD, MGI, and BOP were reassessed and recorded in the periodontal chart.

The study measured these clinical parameters at baseline, and at months one and three. Probing pocket depth was measured at six sites per tooth using the Williams periodontal probe. The Modified Index for gingival inflammation used a scale from 0 (no inflammation) to 4 (severe inflammation), with mean scores calculated for each patient. The BOP test was scored as 100% if bleeding occurred and 0% if not; mean scores were calculated for each patient.

Standardized periodontal charts and clinical observation forms were used for data collection. Statistical evaluation was performed using SPSS software version 22. Mean and standard deviation were used for all clinical parameters. The Shapiro-Wilk test evaluated the normality of the data. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for normally distributed variables, and chi-square tests were used for categorical data. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. Bleeding on probing and MGI scores were presented through histogram charts to show their distribution patterns among the three groups.

Group comparisons at each time point were performed using separate one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests. Within-group changes over time were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA or paired t-tests where appropriate.

This research implemented all ethical aspects from the Declaration of Helsinki to guide its procedures. For this study, the Research Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences granted ethical approval. Participation in the study started with the provision of thorough study protocol details to all participants, who then signed an informed consent document before study admittance. Participation was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time without repercussions.

All participants received identical oral hygiene kits and were instructed not to use any other mouthwashes or antimicrobial products during the study. Full-mouth SRP was performed under local anesthesia by a single calibrated dental student using an ultrasonic scaler followed by Gracey curettes, completed in two sessions within 48 hours. The examiner was calibrated prior to the study. Intra-examiner reliability, assessed by duplicate measurements in 10% of subjects, showed an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.92 for PPD. Adherence was assessed through bottle return inspection and participant self-report at each visit. The study was conducted over six months and included the primary phases in Table 1.

| Phases | Activity |

|---|---|

| Baseline (week 0) | Patient selection, informed consent, baseline examination (probing 1), SRP, and randomization into study groups |

| Week 1 - month 1 | Initiation of mouthwash use, adherence monitoring |

| Month 1 | Follow-up examination (probing 2) |

| Month 3 | Final evaluation (probing 3) and data analysis |

Abbreviation: SRP, scaling and root planning.

By following this structured methodology, this study aims to provide high-quality evidence on the clinical effectiveness of probiotic mouthwash in periodontal therapy.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

A total of 51 individuals were assessed for eligibility. Nine patients were excluded before randomization due to not meeting inclusion criteria or declining participation. Forty-two participants were randomized and completed all follow-up visits, with no loss to follow-up. This is consistent with the CONSORT flow diagram. These individuals were randomly assigned to three groups (probiotic mouthwash, chlorhexidine mouthwash, and normal saline) with 14 patients in each group. The normality of data distribution was confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, allowing for parametric statistical analysis.

All 42 participants received their allocated interventions, completed the one-month intervention period, and attended all follow-up assessments at one and three months. No participants were lost to follow-up, and all 42 were included in the final analysis.

3.2. Probing Pocket Depth

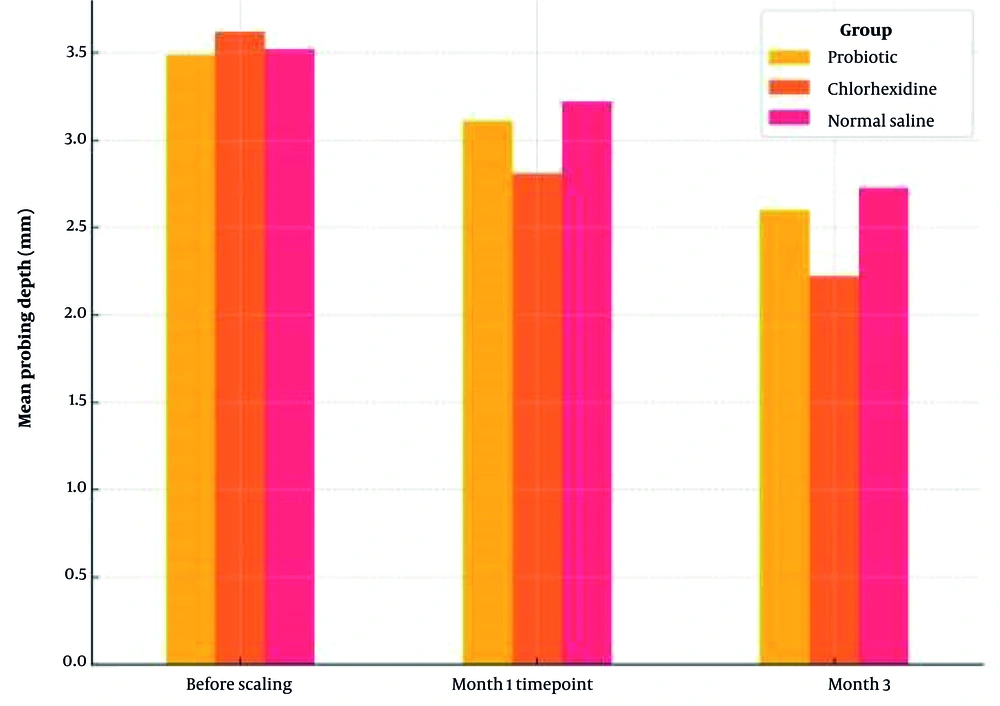

Table 2 presents the mean PPD across the three groups at baseline, one month, and three months’ post-treatment. Before SRP, there were no significant differences in PPD among the groups (P = 0.735). One month after treatment, the chlorhexidine group exhibited the most substantial reduction in PPD, with a statistically significant difference compared to the normal saline group (P = 0.039). By the third month, the difference was even more pronounced, with the chlorhexidine group maintaining significantly lower PPD values than both the probiotic and normal saline groups (P = 0.001). Figure 1 illustrates the comparative reduction in PPD over time.

| Groups | Before Scaling | Month 1 | Month 3 | P-Value (Within-Group b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic | 3.49 ± 0.52 | 3.11 ± 0.48 | 2.6 ± 0.45 | < 0.001 |

| Chlorhexidine | 3.62 ± 0.49 | 2.81 ± 0.43 | 2.22 ± 0.41 | < 0.001 |

| Normal saline | 3.52 ± 0.55 | 3.22 ± 0.51 | 2.73 ± 0.47 | 0.001 |

| P-value (between-group ANOVA) | 0.735 | 0.039 | 0.001 |

Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance.

a Values are expresses as mean  ± SD, mm.

b Within-group P-value from repeated measures ANOVA or paired t-test comparing baseline to month 3.

Post-hoc analysis using Tukey's HSD test revealed that the significant between-group difference in PPD at month 3 was primarily driven by the chlorhexidine group. The chlorhexidine mouthwash demonstrated a statistically superior reduction in PPD compared to both the probiotic group (mean difference: -0.38 mm; 95% CI: -0.65 to -0.11; P = 0.005) and the normal saline placebo group (mean difference: -0.51 mm; 95% CI: -0.78 to -0.24; P < 0.001). No significant difference was observed between the probiotic and placebo groups (mean difference: -0.13 mm; 95% CI: -0.40 to 0.14; P = 0.490) as shown in Table 3.

| Comparison | Mean Difference (mm) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorhexidine vs. probiotic | -0.38 | -0.65 to -0.11 | 0.005 |

| Chlorhexidine vs. placebo | -0.51 | -0.78 to -0.24 | < 0.001 |

| Probiotic vs. placebo | -0.13 | -0.40 to 0.14 | 0.490 |

3.3. Modified Gingival Index

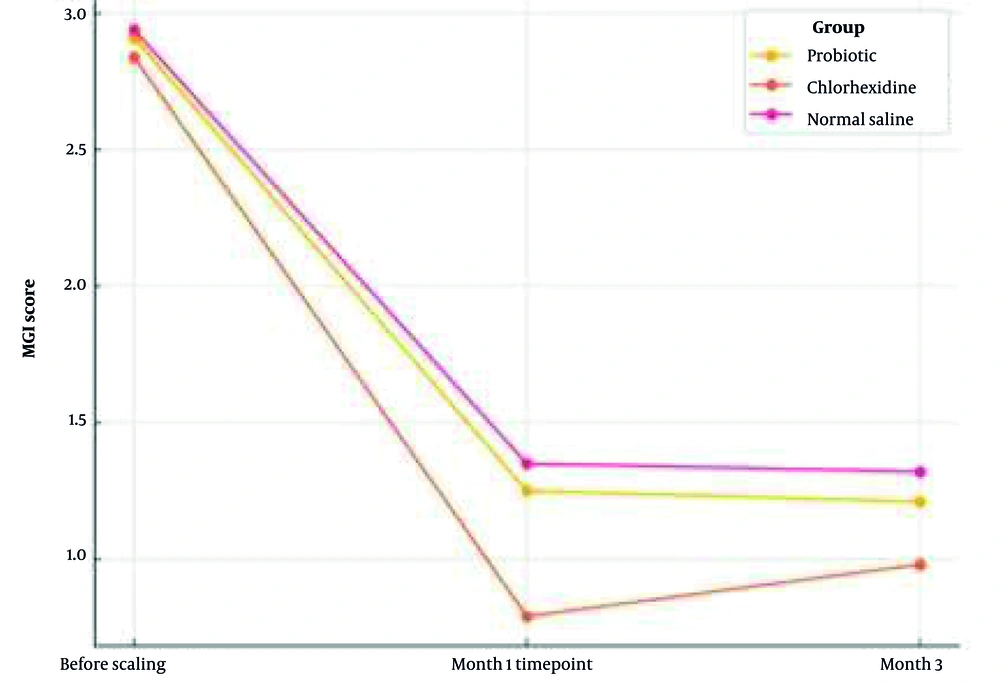

The research shows MGI scores from Table 4 at different times as means. The groups showed similar MGI levels at the beginning of the study (P = 0.830). The chlorhexidine group displayed the minimal MGI scores, leading to significant differences compared to the other treatment groups at the one-month follow-up (P = 0.003). A statistical analysis conducted at the third month revealed differences to be insignificant (P = 0.075). The MGI score evolution of the three study groups can be observed in Figure 2 through time.

| Groups | Before Scaling | Month 1 | Month 3 | P-Value (Within-Group b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic | 2.91 ± 0.42 | 1.25 ± 0.35 | 1.21 ± 0.33 | < 0.001 |

| Chlorhexidine | 2.84 ± 0.48 | 0.79 ± 0.25 | 0.98 ± 0.28 | < 0.001 |

| Normal saline | 2.94 ± 0.35 | 1.35 ± 0.38 | 1.32 ± 0.36 | < 0.001 |

| P-value (between-group ANOVA) | 0.830 | 0.003 | 0.075 |

Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance.

a Values are expresses as mean  ± SD.

b Within-group P-value from repeated measures ANOVA or paired t-test comparing baseline to month 3.

The between-group differences in MGI at the one-month follow-up were further elucidated by post-hoc testing. The chlorhexidine group showed significantly greater improvement in MGI scores compared to both the probiotic group (mean difference: -0.46; 95% CI: -0.75 to -0.17; P = 0.001) and the normal saline placebo group (mean difference: -0.56; 95% CI: -0.85 to -0.27; P < 0.001). The difference between the probiotic and placebo groups did not reach statistical significance (mean difference: -0.10; 95% CI: -0.39 to 0.19; P = 0.690), as shown in Table 5.

| Comparison | Mean Difference | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorhexidine vs. probiotic | -0.46 | -0.75 to -0.17 | 0.001 |

| Chlorhexidine vs. placebo | -0.56 | -0.85 to -0.27 | < 0.001 |

| Probiotic vs. placebo | -0.10 | -0.39 to 0.19 | 0.690 |

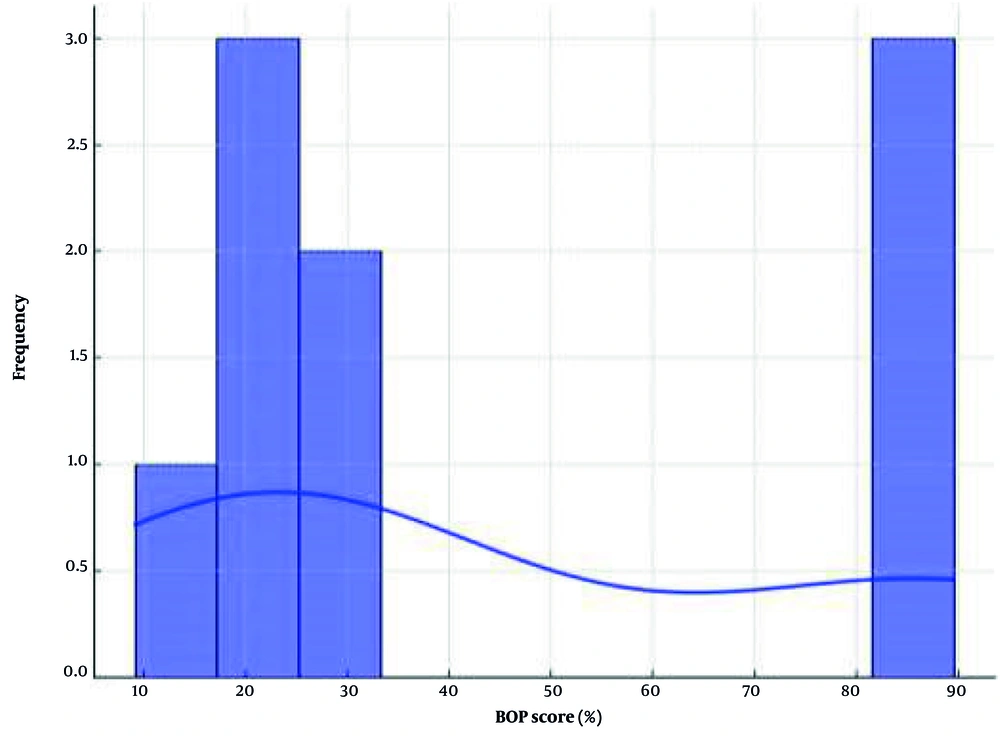

3.4. Bleeding on Probing

Table 6 includes data about the BOP percentages during baseline testing as well as one month and three months after treatment. All groups showed similar results before starting the treatment protocol (P = 0.787). Chlorhexidine treatment brought about lower BOP scores compared to both probiotic and normal saline therapy at the one-month measurement point (P = 0.006). Results at the three-month follow-up no longer proved statistically different among groups (P = 0.458). The distribution pattern of BOP scores appears in Figure 3 through a histogram representation.

| Group | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 3 | P-Value (Within-Group b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotic | 85.86 ± 8.24 | 22.71 ± 6.35 | 30.00 ± 7.15 | < 0.001 |

| Chlorhexidine | 87.00 ± 7.89 | 9.14 ± 3.82 | 27.57 ± 6.92 | < 0.001 |

| Normal saline | 89.57 ± 8.45 | 21.71 ± 6.28 | 24.00 ± 6.74 | < 0.001 |

| P-value (between-group ANOVA) | 0.787 | 0.006 | 0.458 |

Abbreviation: ANOVA, analysis of variance.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD, (%).

b Within-group P-value from repeated measures ANOVA or paired t-test comparing baseline to month 3.

Post-hoc analysis of the BOP percentages at month 1 clarified the nature of the observed between-group differences. The chlorhexidine group exhibited significantly greater reduction in BOP compared to both the probiotic group (mean difference: -13.57%; 95% CI: -22.10 to -5.04; P = 0.001) and the normal saline placebo group (mean difference: -12.57%; 95% CI: -21.10 to -4.04; P = 0.003). No significant difference was found between the probiotic and placebo groups (mean difference: 1.00%; 95% CI: -7.53 to 9.53; P = 0.950), as shown in Table 7.

| Comparison | Mean Difference (%) | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorhexidine vs. probiotic | -13.57 | -22.10 to -5.04 | 0.001 |

| Chlorhexidine vs. placebo | -12.57 | -21.10 to -4.04 | 0.003 |

| Probiotic vs. placebo | 1.00 | -7.53 to 9.53 | 0.950 |

3.5. Statistical Analysis and Interpretation

The statistical breakdown showed that SRP delivered beneficial results to all groups, but chlorhexidine treatment produced stronger inflammation-reducing effects together with bleeding reduction. The clinical benefits related to probiotic mouthwash treatment were comparable to those of placebo mouthwash, indicating that L. salivarius NK02 showed limited effectiveness regarding periodontal parameter enhancement.

Figure and table data from this section display numeric and visual evidence demonstrating how the three treatments performed relative to each other.

The comprehensive statistical analysis, including effect sizes and confidence intervals, provides robust evidence for the superior short-term efficacy of chlorhexidine mouthwash as an adjunct to SRP. While all groups showed significant within-group improvements over time, the between-group comparisons clearly demonstrate that chlorhexidine offers additional clinical benefits in periodontal parameters compared to both probiotic and placebo treatments during the active intervention phase. Tooth staining was reported by 4 participants in the chlorhexidine group. No other adverse events were reported. When questioned, no participants or the examiner could correctly guess their group assignment beyond chance, supporting the success of blinding.

4. Discussion

This research evaluated the therapeutic outcomes between probiotic mouthwash utilizing L. salivarius NK02, chlorhexidine, and placebo-based normal saline in patients with mild to moderate chronic periodontitis. The study was conducted with patients who received periodontal care at the Periodontology Department of the Dental School in 2019 and had a periodontist-diagnosed chronic periodontitis status. Each patient received SRP before random distribution into one of the three assigned groups. Medical professionals measured PPD, MGI, and BOP at baseline, and again at one month and three months after treatment.

Single therapeutic use of SRP produced substantial improvements in periodontal parameters, including reductions in PPD, MGI, and BOP, regardless of the mouthwash treatment. Evaluation of intergroup comparisons showed considerable differences, particularly during the first and third month of follow-up. Subjects exposed to chlorhexidine mouthwash at one month showed the most substantial PPD reduction compared to those rinsing with normal saline, yet received no different outcomes from participants with the probiotic rinse. After three months, the chlorhexidine group maintained lower periodontal pocket depths than all study groups, including those who received probiotics and normal saline. Modified Gingival Index and BOP scores displayed substantial declines in the chlorhexidine group at one month, although by the three-month mark, evaluations among all groups were nonsignificant.

Researchers in four publications (7, 19-21) and two publications (20, 22) have established PPD, MGI, and BOP as significant measures for periodontal disease assessment. These parameters were selected in the present study to determine how effectively probiotic mouthwash works with traditional periodontal treatments.

Research findings from this investigation further support how chlorhexidine decreases inflammation and enhances clinical attachment levels (CALs), as demonstrated in previous studies (7, 19). The clinical advantages of using L. salivarius NK02 mouthwash as an adjunct therapy during periodontal treatment proved similar to those of placebo-based mouthwash. This indicates that L. salivarius NK02 likely lacks potent clinical effects on periodontitis in this treatment combination. The findings from this study match the research of Iwasaki et al. (20) and another research study (22) but oppose the findings reported in Vivekananda et al. (18), Vicario et al. (23), and Morales et al. (24), who demonstrated significant improvements with probiotics. The discrepancies may stem from differences in used probiotic strains, variations in disease severity, study design approaches, and sample size variations.

All study groups demonstrated significant improvement in PPD measurements, yet chlorhexidine sustained the most substantial effect over time. The study findings match results documented in (7, 19, 20), which demonstrated comparable probing depth improvements from chlorhexidine usage. Our research yields opposite results when compared to Vivekananda et al. (18) and Morales et al. (24), where probiotics provided better performance than chlorhexidine. The research results might be affected by contrasting approaches to selecting patients, intervention durations, and strains of probiotics used.

The one-month assessment revealed major MGI decreases in patients who received chlorhexidine treatment, yet the three-month evaluation showed no meaningful variations. The initial powerful anti-inflammatory capability of chlorhexidine seems to decrease as time progresses. The research matches the results in (18, 20, 22) regarding the long-term stability of probiotic anti-inflammatory effects. Patients who received chlorhexidine therapy showed lower bleeding measures on the one-month BOP test, although group comparisons became statistically even at three months. The research indicates that chlorhexidine creates potent initial benefits against gingival inflammation, yet these anti-inflammatory effects diminish after the medicine stops being used. Past research by (7, 19) showed similar results, while Vivekananda et al. (18) and Morales et al. (24) found that probiotic therapy produced extended clinical benefits.

Laboratory-proven antibacterial properties of the human-derived strain L. salivarius NK02 (21) did not lead to relevant changes in periodontitis therapy results, which paralleled placebo group outcomes. The results of inflammatory parameter evaluation during the study period indicate that probiotics show less clinical impact compared to chlorhexidine in treating periodontitis.

One reason for the lack of probiotic mouthwash effectiveness may be the period of probiotic consumption. In the current research, mouthwashes were administered for only one month, and their effect was recorded up to three months. Some authors have suggested that longer periods of probiotic consumption may yield higher benefits (6, 25). Further, study design disparities could have explained the noted variations. Some prior studies investigated probiotics in supportive therapy rather than active periodontal treatment, which could result in different outcomes.

A second factor is the probiotic strain type used. Different probiotic strains have diverse effects on oral microbiota and host immune response. While L. reuteri and Bifidobacterium have been reported to be beneficial in some studies, L. salivarius NK02 is not necessarily as effective in periodontal inflammation modulation. Further research is needed to establish the most effective probiotic strains for the treatment of periodontal disease.

This study also had a few limitations. There was a small sample size, and follow-up studies were done for a short duration of three months. Larger sample size and longer follow-up studies are recommended to assess the long-term impact of probiotic therapy. Also, microbiological analysis of subgingival plaque would provide better insight into the direct mechanisms of probiotic action in periodontal health.

Our findings regarding the superior short-term efficacy of chlorhexidine are consistent with its well-established broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, as further supported by recent comparative studies (1). The study findings showed that after SRP, all groups received benefits, with chlorhexidine mouthwash yielding the strongest widespread benefits regarding PPD, MGI, and BOP reduction. The differences between groups in inflammatory parameters became minimal at the three-month follow-up. The short-term clinical performance of L. salivarius NK02-based probiotic mouthwash remained comparable to placebo treatments, thereby disqualifying this strain from serving as an ideal substitute for chlorhexidine in periodontal management. The documented adverse side effects from chlorhexidine usage for periodontitis require additional research to identify more secure probiotic strains that can serve as effective adjunctive periodontitis treatment.

The statistical approach used in this study does not fully model the correlation of repeated measurements within the same individuals. More advanced mixed-effects or repeated-measures modeling would have been preferable; however, the relatively small sample size and exploratory nature of the study limited the feasibility of such analyses. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted as suggestive rather than conclusive. Quantitative adherence data were not recorded, which should be considered a limitation. More investigations should concentrate on developing optimal probiotic products along with treatment duration assessments and individual patient needs to understand their effects on periodontal wellness.

4.1. Conclusions

Although probiotic treatment has been considered a promising adjuvant therapy for periodontal infections, the findings of this study suggest a short-term advantage of chlorhexidine under the conditions of this study. These probiotic findings are preliminary and may depend on strain, dose, and duration. Future studies must examine multiple strains of probiotics, establish ideal dosing schedules, and examine longer durations of treatment to determine if probiotics can serve as an effective replacement for traditional antimicrobial regimens. Additionally, a greater sample size and extended follow-up are recommended to evaluate the long-term stability of treatment. Research into the microbiological effect of probiotic treatment using DNA sequencing and bacterial culture techniques has the potential to elucidate mechanisms for the probiotic effects on oral biofilm and immune system function. Overall, while SRP by itself promotes periodontal health, treatment with adjunctive chlorhexidine yields superior short-term results in inflammation reduction and clinical attachment loss. However, due to the limitations of such a treatment, other therapeutic options such as probiotics need to be investigated. Although the L. salivarius NK02 mouthwash used in the present study failed to show any significant clinical advantage, future investigations into different compositions of probiotics and treatment periods may determine a better, biocompatible, and economical solution for the management of periodontitis.

This study has limitations, including a relatively small sample size and a short follow-up period of three months. Therefore, our conclusions should be interpreted with caution. Future research should not only explore different probiotic strains and regimens but also investigate other biocompatible alternatives, such as herbal mouthwashes, to find sustainable solutions for periodontitis management (26).