1. Background

The phrase NPO, meaning "nil per os", was defined in the 1960s and is derived from a Latin term aimed at minimizing the risk of regurgitation or pulmonary aspiration (1). However, if surgery is scheduled for later in the day, resulting in prolonged fasting time, it can lead to severe complications such as dehydration, dry mouth, hunger, thirst, acute kidney injury, anxiety, elevated glucagon levels, insulin resistance, hypovolemia, electrolyte imbalances, decreased insulin levels, postoperative hyperglycemia, headaches, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and longer hospital stays (2-6). Conversely, shorter fasting time can be beneficial; thus, traditional guidelines have been revised in recent years (7, 8).

The American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) and Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) have recommended multimodal protocols that allow clear liquids and solids up to 2 and 6 hours before surgery, respectively (9, 10). Despite the availability of these new guidelines, studies report that unusual practices persist in many hospitals (11-14). Being knowledgeable about new guidelines and collaboration among anesthesiologists, surgeons, and nurses are essential to improve perioperative protocols (14, 15). To the best of our knowledge, no study on this topic has been conducted in Iran, let alone in Guilan province. Therefore, the results of this survey will help shed light on the complications associated with prolonged NPO times in surgical patients.

2. Objectives

This study was conducted to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of physicians and residents in the anesthesia and surgical departments regarding preoperative fasting time.

3. Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted in teaching hospitals affiliated with Guilan University of Medical Sciences (GUMS). First, the study protocol was approved by the Vice-Chancellor for Research, and an ethics code was obtained.

1. Inclusion criteria: All faculty members and residents of the anesthesia and surgery departments who agreed to participate in the study.

2. Exclusion criteria: Individuals unwilling to participate, and incomplete questionnaires.

The scoring range was from -14 to 14, with higher scores indicating greater knowledge. The data collection tool was a researcher-made questionnaire consisting of three sections. The first part included demographic information; the second part consisted of 14 questions to assess physicians' knowledge. Correct answers were scored as 1-point, incorrect answers as -1 point, and "I don't know" responses as 0 points. The third section included 5 questions to evaluate physicians' performance. Scoring was done using a Likert scale ranging from 3 (always) to 1 (never), with a total score range of 5 to 15; higher scores indicated better performance. The sampling method for this study was total census. To confirm the content validity of the questionnaire, it was administered to 10 faculty members from the anesthesia department. Content validity for all questions was above 0.62. To determine the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha was calculated, yielding a value of 0.70.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

After data collection, the information was entered into SPSS version 21. Mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values, 95% confidence intervals, independent t-tests, one-way ANOVA, and Pearson correlation coefficients were used for data analysis. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered for all tests in this study.

3.2. Ethical Issues/Statement

The Vice-Chancellor for Research of GUMS approved the study protocol and the ethics code of IR.GUMS.REC.1402.104 was received. The purpose of the study and the confidentiality of the information were explained to the participants and informed consent was obtained.

4. Results

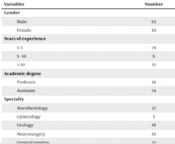

A total of 93 physicians, with an average work experience of 5.15 ± 5.7 years (ranging from 1 to 26 years), participated in the study. Among them, 19 (20.4%) were professor members, and 74 (79.6%) were assistants. The majority of participants were from the General Surgery department (32 participants, 34.4%), followed by the Anesthesiology department (27 participants, 29%; Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 63 (67.7) |

| Female | 30 (32.3) |

| Years of experience | |

| ≤ 5 | 74 (79.6) |

| 5 - 10 | 6 (6.5) |

| > 10 | 13 (14) |

| Mean ± SD (min - max) | 5.15 ± 5.7 (1 - 26) |

| Academic degree | |

| Specialist | 19 (20.4) |

| Resident | 74 (79.6) |

| Specialty | |

| Anesthesiology | 27 (29) |

| Gynecology | 5 (5.4) |

| Urology | 10 (10.8) |

| Neurosurgery | 10 (10.8) |

| General surgery | 32 (34.4) |

| ENT surgery | 2 (2.2) |

| Ophthalmology | 4 (4.3) |

| Thoracic surgery | 3 (3.2) |

Seventy-eight participants (83.9%) for solids knew the correct answer regarding the NPO time for solids, while only 46 (49.5%) knew the correct answer for clear fluids. The frequency of answers provided by physicians from the surgical and anesthesia departments to performance-related questions is shown in Table 2. The frequency distribution of physicians’ responses to questions regarding their performance is presented in Table 3.

| Questions and Answers | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| According to the new guideline, how many hours is the appropriate fasting period for a patient before surgery regarding filtered fluids? | |

| 2 | 46 (49.5) |

| 4 | 24 (25.8) |

| 6 | 16 (17.2) |

| I don't know | 7 (7.5) |

| According to the new guideline, how many hours is the appropriate fasting period for a patient before surgery regarding solids? | |

| 4 - 6 | 9 (9.7) |

| 6 - 8 | 78 (83.9) |

| 10 - 12 | 5 (5.4) |

| I don't know | 1 (1.1) |

| Is anxiety a side effect of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 81 (87.1) |

| No | 9 (9.7) |

| I don't know | 3 (3.2) |

| Is hemodynamic disturbance a complication of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 61 (65.6) |

| No | 29 (31.2) |

| I don't know | 3 (3.2) |

| Is dehydration a side effect of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 78 (83.9) |

| No | 11 (11.8) |

| I don't know | 4 (4.3) |

| Is insulin resistance a side effect of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 47 (50.5) |

| No | 33 (35.5) |

| I don't know | 13 (14) |

| Is an increased risk of aspiration a side effect of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 21 (22.6) |

| No | 63 (67.7) |

| I don't know | 9 (9.7) |

| Is increased postoperative pain a side effect of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 28 (30.1) |

| No | 42 (45.2) |

| I don't know | 23 (24.7) |

| Is increased nausea and vomiting after surgery a side effect of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 44 (47.3) |

| No | 37 (39.8) |

| I don't know | 12 (12.9) |

| Are increased postoperative inflammatory reactions a side effect of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 34 (36.6) |

| No | 39 (41.9) |

| I don't know | 20 (21.5) |

| Is prolonged recovery a side effect of prolonged fasting before surgery? | |

| Yes | 48 (51.6) |

| No | 29 (31.2) |

| I don't know | 16 (17.2) |

| Who is responsible for determining the exact time of fasting? | |

| Nurse | 2 (2.2) |

| Surgeon | 23 (24.7) |

| Anesthesiologist | 67 (72) |

| I don't know | 1 (1.1) |

| Does a longer fasting period make the patient safer? | |

| Yes | 10 (10.8) |

| No | 77 (82.8) |

| I don't know | 6 (6.5) |

| Is the fasting time different in patients with high BMI than in other people? | |

| Yes | 52 (55.9) |

| No | 31 (33.3) |

| I don't know | 10 (10.8) |

| Questions and Answers | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| As a surgeon/anesthesiologist, I intervene in determining the patient's fasting time based on the time of surgery. | |

| Always (3) | 56 (60.2) |

| Sometimes (2) | 27 (29) |

| Never (1) | 10 (10.8) |

| I recommend consuming 100 cc of sweet, strained liquids, such as sweet tea, 2 h before the procedure. | |

| Always (3) | 14 (15.1) |

| Sometimes (2) | 37 (39.8) |

| Never (1) | 42 (45.2) |

| I postpone surgery for a patient who chewed gum or sucked candy immediately before induction of anesthesia. | |

| Always (3) | 14 (15.1) |

| Sometimes (2) | 20 (21.5) |

| Never (1) | 59 (63.4) |

| I recommend routine administration of antacids, metoclopramide, and H2 receptor antagonists before elective surgery. | |

| Always (3) | 8 (8.6) |

| Sometimes (2) | 65 (69.9) |

| Never (1) | 20 (21.5) |

| I allow adults to drink 100 cc of water along with oral medications before surgery, and 75 cc in children, up to one hour before anesthesia induction. | |

| Always (3) | 45 (48.4) |

| Sometimes (2) | 30 (32.3) |

| Never (1) | 18 (19.4) |

The results indicated a statistically significant difference in the total knowledge scores based on educational fields (P = 0.005, Table 4). Additionally, a statistically significant difference was found in the total performance scores based on the gender of the physicians (P = 0.002), years of experience (P = 0.018), academic degree (P = 0.038), and educational fields (P < 0.001, Table 5).

| Variables | Number | Min, Max | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.087 | |||

| Male | 63 | -10, 13 | 2.79 ± 4.7 | |

| Female | 30 | -9, 14 | 4.66 ± 5.23 | |

| Years of experience | 0.121 | |||

| ≤ 5 | 74 | -9, 11 | 2.95 ± 4.56 | |

| 5 - 10 | 6 | -10, 12 | 3.16 ± 7.96 | |

| > 10 | 13 | 0, 14 | 6 ± 4.96 | |

| Academic degree | 0.057 | |||

| Professor | 19 | -10, 14 | 5.31 ± 5.96 | |

| Assistant | 74 | -9, 11 | 2.9 ± 4.54 | |

| Specialty | 0.005 | |||

| Anesthesiology | 27 | -4, 14 | 6.14 ± 4.02 | |

| Gynecology | 5 | -9, 6 | 0.6 ± 5.81 | |

| Urology | 10 | -3, 8 | 1.8 ± 3.58 | |

| Neurosurgery | 10 | 0, 10 | 4.7 ± 4 | |

| General surgery | 32 | -7, 11 | 1.46 ± 4.79 | |

| ENT | 2 | 4, 9 | 6.5 ± 3.53 | |

| Ophthalmology | 4 | 2, 9 | 5.25 ± 3.77 | |

| Thoracic surgery | 3 | -10, 9 | 0.33 ± 9.6 |

| Variables | Number | Min, Max | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.002 | |||

| Male | 63 | 5, 12 | 9.53 ± 1.49 | |

| Female | 30 | 6, 14 | 10.7 ± 1.85 | |

| Years of experience | 9.68 ± 1.7 | 0.018 | ||

| ≤ 5 | 74 | 5, 14 | 11.5 ± 1.87 | |

| 5 - 10 | 6 | 9, 14 | 10.46 ± 1.05 | |

| > 10 | 13 | 8, 12 | 10.63 ± 1.53 | |

| Academic degree | 9.72 ± 1.69 | 0.038 | ||

| Professor | 19 | 8, 14 | 11.03 ± 1.78 | |

| Assistant | 74 | 5, 14 | 9.8 ± 1.78 | |

| Specialty | 8 ± 1.69 | 0.0001 | ||

| Anesthesiology | 27 | 6, 14 | 8.6 ± 0.69 | |

| Gynecology | 5 | 8, 12 | 10.06 ± 1.07 | |

| Urology | 10 | 5, 10 | 10.5 ± 2.12 | |

| Neurosurgery | 10 | 8, 10 | 8.75 ± 0.95 | |

| General surgery | 32 | 8, 12 | 10.33 ± 0.57 | |

| ENT | 2 | 9, 12 | 10.7 ± 1.85 | |

| Ophthalmology | 4 | 8, 10 | 9.68 ± 1.7 | |

| Thoracic surgery | 3 | 10, 11 | 11.5 ± 1.87 |

5. Discussion

Evidence-based studies have demonstrated that being NPO after midnight increases patient discomfort and leads to negative outcomes (16, 17). Compared to patients undergoing surgery in the morning shift, patients admitted for evening surgeries are more likely to experience longer fasting times (13). One of the main factors contributing to prolonged fasting time is that the medical team and nursing staff are either unaware of the new guidelines or prefer to ignore them in favor of traditional, simpler strategies (18). This descriptive, cross-sectional study revealed that despite the existence of revised guidelines in recent years, there is insufficient knowledge about NPO that requires attention (19). The response rate among faculty members and residents was approximately 25% and 50%, respectively, indicating a low rate. It seems that in addition to physicians being reluctant to be involved in this process and considering it as an additional responsibility, the method of data collection was also not optimal. If direct interviews were performed, the results might be more acceptable. The results of this study showed that less than half of the participants were aware that patients could drink small amounts of clear liquids up to two hours before surgery, with more than 50% being completely unaware of this guideline. Studies have shown that depriving patients of fluids for more than two hours is unnecessary and can lead to physical and emotional complications (20). Regarding the appropriate fasting time for solids, 83.9% gave the correct answer, which was determined as 6 - 8 hours. Another noticeable finding was that 9.7% of physicians believed that a preoperative fasting time of 4 - 6 hours was sufficient for solids, which can create dangerous conditions, especially when consuming fatty foods, or lead to cancellation on the day of surgery.

A significant number of participants (67.7%) did not believe that prolonged NPO times increased the risk of aspiration. Almost half of them did not recognize the connection between postoperative pain and prolonged fasting times. Considering the potential side effects of postoperative pain, including sympathetic stimulation, delayed recovery, and impaired wound healing, it is essential to address the importance of avoiding long and unnecessary fasting periods (21).

Anesthesiologists had higher performance scores, which could be linked to their role in determining fasting times, as 72% of participants stated that anesthesiologists were responsible for determining the appropriate fasting times. Moreover, anesthesiologists are increasingly faced with challenges related to patients' fasting times. Gupta et al. from India conducted an observational study investigating the knowledge status of postgraduate trainees in anesthesiology and surgical specialties regarding preoperative fasting guidelines, as well as their attitude and practice. They found that 89.8% of respondents could not accurately describe the revised preoperative fasting guidelines published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists pertaining to adults, and 30.7% were unaware of the benefits of limiting NPO times (22). Zhu et al. from China assessed actual fasting times among patients scheduled for elective surgeries and reported excessive NPO durations contrary to recommended guidelines (23). A recent literature review indicated that anesthesiologists had greater knowledge of new preoperative fasting guidelines than other healthcare professionals; however, actual fasting times were found to be relatively longer than prescribed (24). Alshurtan et al. from Saudi Arabia conducted a cross-sectional study assessing the general population's knowledge and attitudes toward preoperative fasting times, reporting that only 1.6% had good knowledge. Older age and female gender were associated with higher knowledge levels (25).

Tsai et al. investigated the level of preoperative fasting knowledge among nursing staff at a tertiary referral center and found that most had inadequate information regarding preoperative fasting guidelines (26). In another study, the preoperative fasting status of patients admitted on the day of surgery was studied. It was found that patients fasted according to their knowledge, experience, and preferences, and often for longer than necessary. They recommended that patients be informed about fasting decisions during pre-operative visits (27).

Regarding the association between preoperative fasting and postoperative nausea and vomiting, postoperative inflammatory reactions, and prolonged recovery, the level of awareness was unacceptable, with more than half of the physicians lacking correct information. When asked who determines the fasting time, most participants identified the anesthesiologist as responsible. While approximately 40 percent of participants did not consider the issue important for intervention, this result contradicts the principles of patient safety. Only 15% of the participants advised patients to drink clear liquids up to 2 hours before the procedure. Given that 49.5% of them were aware of this guideline, this outcome indicates less-than-ideal conditions.

In fact, the performance of the doctors was not commensurate with their knowledge and was lower than expected. Regarding the consumption of water for preoperative medications, more than half of the doctors did not emphasize this aspect, which is concerning since not taking certain medications or taking them without water can lead to complications for the patient. Some physicians expressed that chewing gum before surgery compromises patient safety, and this lack of awareness can result in unnecessary cancellations. Interestingly, women achieved higher scores in both knowledge and performance, which was consistent with some previous studies, indicating that female physicians pay more attention to soft skills (28). In terms of work experience, as anticipated, greater experience correlated with higher scores. Additionally, specialists received higher scores than assistants, which was also expected. However, considering that this topic is fundamental and should be taught to assistants from the outset of their training, this significant difference is not an acceptable outcome. In fact, raising knowledge and providing accurate information on this subject is not a difficult or complex process. Furthermore, the data were collected from university centers where residents are being trained, thus it is expected that they would adhere to new guidelines.

Overall, the topic of fasting time is multifactorial and depends on the time of surgery, patients' culture and beliefs, physicians’ and nursing staff responsibility and knowledge, and the proper scheduling of patients based on the operating room conditions. Therefore, to achieve the goals, inter-departmental collaboration is essential and further studies are required to identify effective solutions to reduce prolonged preoperative fasting time (27, 29, 30).

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the awareness and performance of physicians regarding the new fasting guidelines require improvement. A comprehensive approach is needed to enhance the knowledge and practices of faculty members and residents concerning revised guidelines on preoperative fasting times. Additionally, it was found that in some instances, physicians do not feel obligated to act according to what they know. Given the importance of this issue and the established impact of prolonged fasting on patient safety, effective educational interventions are necessary. Targeted education for residents and integration of the topic into the curriculum can improve the situation.

5.2. Suggestions

Given that a substantial number of patients undergo surgery in private hospitals, it is recommended that a similar study be conducted involving the private sector. Comparing the results between the private sector and public academic centers would provide valuable insights.

5.3. Limitations

This study provided valuable information; however, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, it was a single-center study focused solely on teaching hospitals. The private sector, which manages a significant number of treatment cases, was not included. Therefore, a well-planned multi-center study is recommended. Secondly, the response rate was low; indeed, a high percentage of physicians did not participate in the study, despite efforts to engage them through face-to-face interviews. It is possible that those who were unaware of the issue and did not pay attention to it refused to participate.