1. Background

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) affects more than 50% of adults aged 65 years and older, significantly impairing quality of life and independence (1). CLBP is closely associated with sarcopenia, muscle weakness, and impaired balance, all of which increase the risk of falls and disability, highlighting the need for targeted exercise interventions (2). Balance and lower extremity strength are critical determinants of physical function and quality of life in older adults. Balance depends on the integrated function of sensory, neurological, and musculoskeletal systems. In individuals with CLBP, balance is often compromised due to reduced proprioception, core muscle weakness, and altered spinal mechanics, resulting in a higher risk of falls (3). Age-related decline in sensory systems and muscle strength further exacerbates these impairments.

Muscular imbalances, particularly involving the core musculature, are common in people with low back pain (4). Weakness of the abdominal muscles can lead to poor posture and excessive loading of the lumbar spine, whereas overactivity or early fatigue of the paraspinal muscles may perpetuate pain (5). Lower extremity strength, especially in the gluteus medius and gluteus maximus, plays an essential role in pelvic stability, gait mechanics, and everyday tasks such as sitting, standing, and walking. In older adults, reduced strength in these muscles directly compromises functional mobility and independence. Research has consistently shown positive correlations between lower extremity strength, gait speed, balance, and performance of activities of daily living (6, 7). Age-related loss of muscle strength therefore has profound implications for mobility and overall quality of life.

Exercise interventions such as dynamic neuromuscular stabilization (DNS) have proven effective in managing CLBP by enhancing core stability and spinal control (8). However, DNS alone may not adequately address gluteal weakness, which is frequently observed in this population. Targeted strengthening of these hip muscles is crucial for restoring pelvic alignment, improving functional stability, and reducing stress on the lumbar spine. Combining DNS with specific gluteal strengthening exercises has been shown to enhance pelvic stability and balance more effectively than DNS alone (9, 10). Strengthening the gluteal muscles also improves dynamic balance, reduces fall risk, and alleviates pain (11). The combined effects of DNS and gluteal exercises in older adults with CLBP remain underexplored. Despite these findings, the combined effects of DNS and gluteal strengthening exercises in older adults with CLBP remain underexplored. To date, no studies have directly compared the efficacy of DNS plus targeted hip-strengthening exercises (DNSHS) versus DNS alone on balance, lower extremity strength, and functional disability. Moreover, this combined intervention has not been specifically investigated in older women with chronic nonspecific low back pain.

2. Objectives

The aim of this study is to evaluate whether adding targeted gluteal strengthening exercises to a DNS program provides superior improvements in balance, lower extremity strength, and functional disability compared to DNS alone in older women with chronic nonspecific low back pain.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

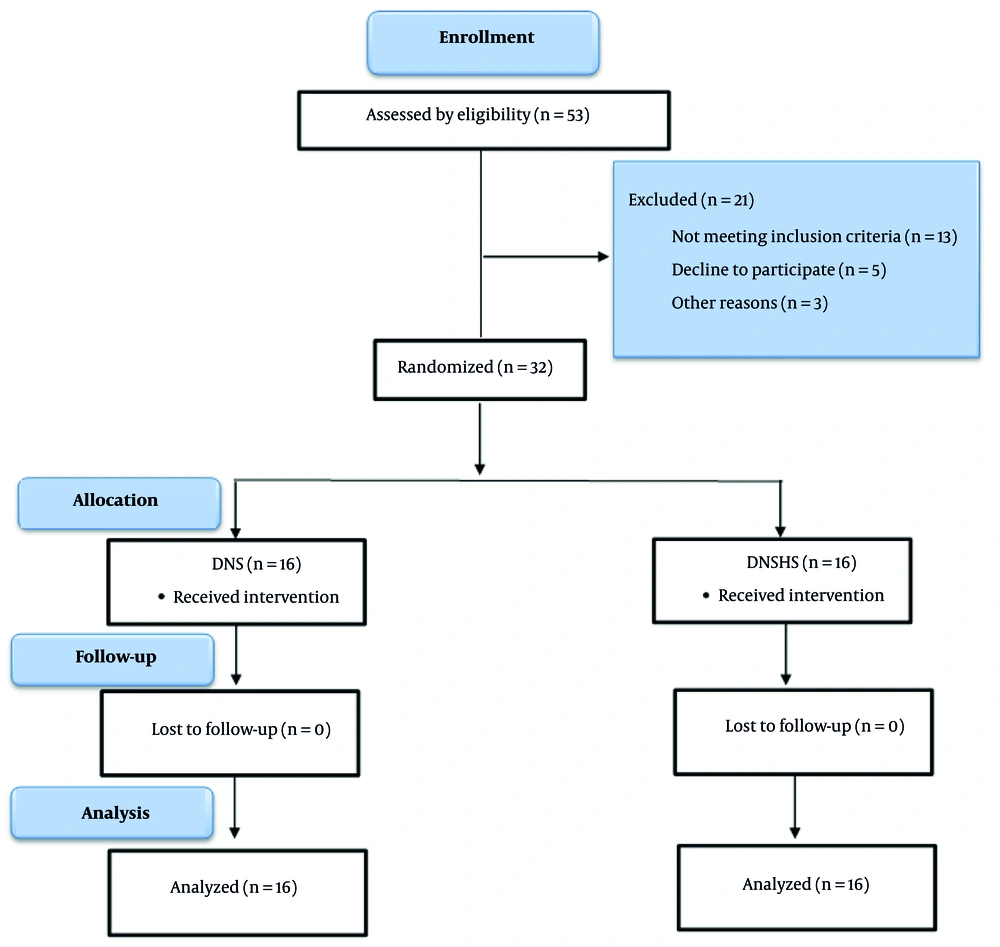

This double-blind, two-group, pre-post quasi-experimental study was conducted at Bu-Ali Sina University’s Sports Science Laboratory (October - December 2024), following CONSORT guidelines and adhering to the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles. Both the participants and the outcome assessor were blinded to group allocation throughout the study (Figure 1).

3.2. Participants

This study recruited women aged 60 - 80 years with chronic non-specific low back pain lasting more than three months and a pain intensity of > 5 on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). Participants were required to be independent in activities of daily living. Eligibility was confirmed by a physician specialist. Exclusion criteria included a history of cardiovascular or respiratory disease, severe lower extremity or spinal injury/surgery, neurological disorders, vestibular dysfunction, or any contraindication to exercise. Participants were also excluded if they reported increased pain or disability during the intervention, were unwilling or unable to continue, withdrew consent, missed more than three sessions, or had a Body Mass Index > 35 kg/m².

3.3. Sample Size

Sample size was calculated using G*Power (v3.1.9.4) based on an expected effect size of 0.307, α = 0.05, and power = 0.80, which yielded a minimum requirement of 24 participants (12 per group). To account for potential dropouts, 32 women were enrolled and randomly allocated to either the DNS or DNSHS group (16 per group).

3.4. Measurements

3.4.1. Lower Limb Strength

Lower extremity strength was assessed using the 30-Second Chair Stand Test (30s-CST), a well-validated and reliable measure for older adults. Participants were instructed to rise from a seated position to full standing and return to seated as many times as possible in 30 seconds, with arms folded across the chest. The score was the total number of complete stand-to-sit cycles performed (12). The 30s-CST has demonstrated excellent test–retest reliability in community-dwelling Iranian older adults, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.89 - 0.97) (13).

3.4.2. Balance

Dynamic balance and functional mobility were evaluated using the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test. Participants rose from a seated position, walked 3 meters at their usual pace, turned around, returned to the chair, and sat down, with the time recorded in seconds. A TUG time <10 seconds indicates good functional mobility, whereas > 20 seconds is associated with an elevated risk of falls (14). The TUG test has shown excellent test–retest reliability in Iranian older adults, with an ICC of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.91 - 0.97) (15).

3.4.3. Disability

Functional disability was assessed using the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), a widely validated and reliable instrument for individuals with chronic low back pain. The questionnaire consists of 24 yes/no items related to limitations in daily activities due to low back pain; the total score ranges from 0 (no disability) to 24 (maximum disability) (16). The Persian version of the RMDQ exhibited excellent test–retest reliability in patients with chronic low back pain, including older adults, with an ICC of 0.91 (95% CI: 0.87 - 0.94) (17).

3.5. Exercise Intervention

3.5.1. Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization Exercises

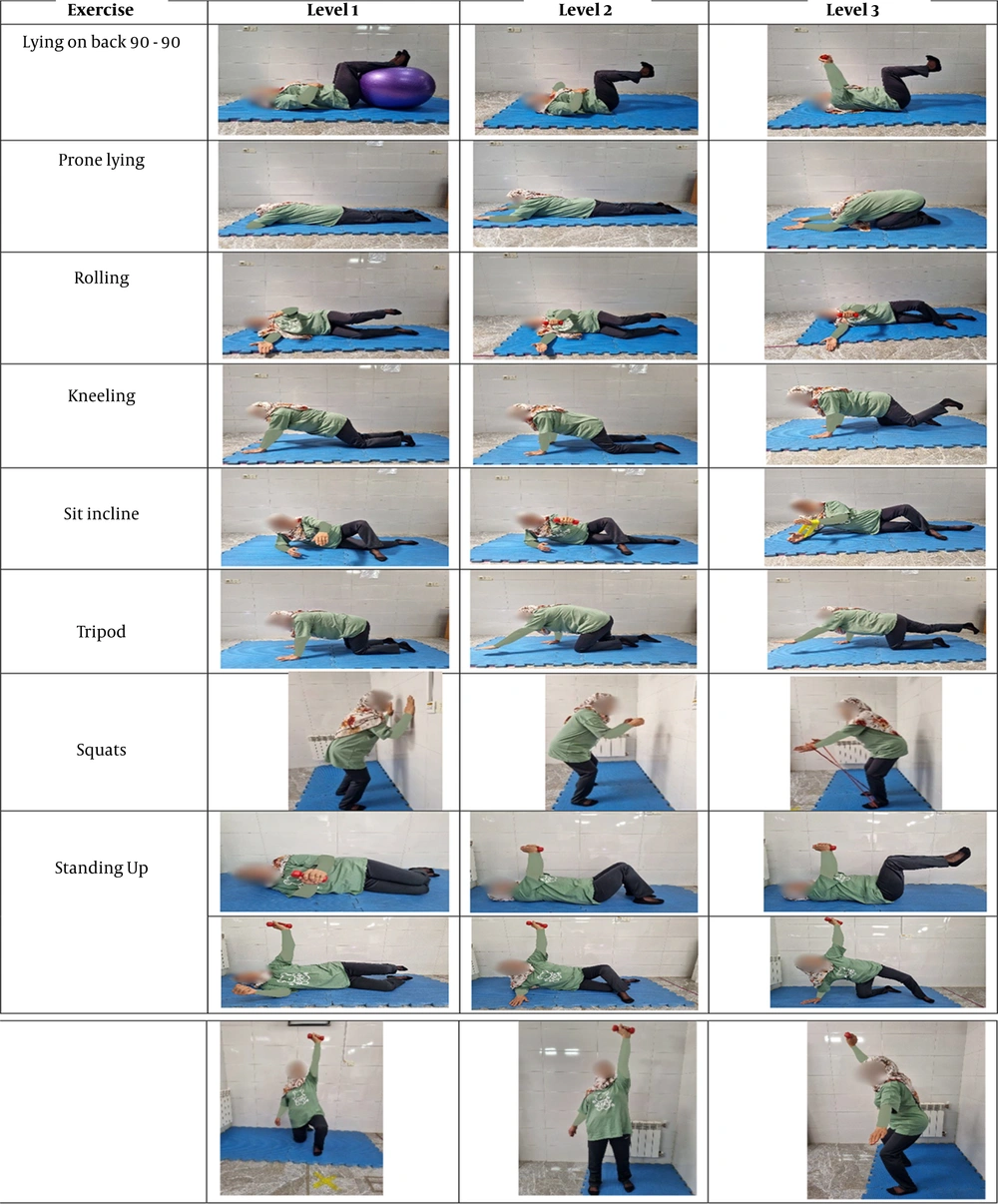

The 8-week DNS protocol consisted of three supervised 50-minute sessions per week. Each session included a 5-minute warm-up and a 5-minute cool-down. Exercise intensity and complexity were progressively increased based on each participant’s tolerance and proficiency. Advancement to more challenging positions was allowed only after the participant demonstrated full mastery of the current stage. Early sessions focused on verbal cues, tactile feedback, and visual guidance to establish correct pelvic, spinal, and thoracic alignment. Throughout the intervention, emphasis was placed on enhancing body awareness, core activation, and proper movement patterns to improve motor control and alleviate pain. Key exercises included Diaphragmatic Breathing, Baby Rock, Prone Stabilization, Supine Bear, Side-Lying Positions, and progressive developmental positions derived from the DNS approach. (Figure 2) (8)

3.5.2. Hip Strengthening Exercises

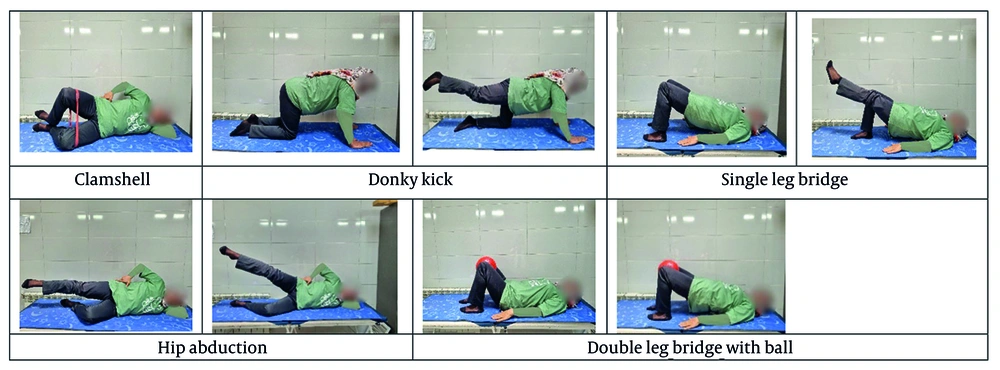

The DNSHS group received, in addition to the standard DNS protocol, a targeted hip-strengthening program consisting of exercises such as Clamshells, Donkey Kicks, and single- and double-leg Bridges. This supplementary training was performed three times per week for eight weeks, with each 30-minute session comprising three sets of 15 repetitions per exercise and 30 - 40 seconds of rest between sets. (Figure 3) (18)

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistical methods were used to analyze the collected data. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. To analyze the data, while adhering to assumptions (normality of data distribution, homogeneity of variances, and homogeneity of covariances), a mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures was employed. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (version 26) at a significance level of 95% with an alpha value of ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

All participants completed the entire intervention and assessment process, with no dropouts. Additionally, no adverse effects related to the training were reported. Descriptive statistics and demographic characteristics for each group, along with the results of the independent t-test, are presented in Table 1. The findings indicated that demographic characteristics were homogeneous across groups, with no significant differences in mean age, weight, or height between the groups (P > 0.05).

Abbreviation: DNS, dynamic neuromuscular stabilization; DNSHS, hip-strengthening exercises.

a Values are expressed as Mean ± SD.

Repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of group (P > 0.05). However, the main effect of time (P < 0.001) and the time × group interaction (P = 0.039) were statistically significant, indicating that the magnitude of improvement in dynamic balance differed between groups. Post-hoc Bonferroni comparisons confirmed significant pre- to post-intervention improvements in both the DNS and DNSHS groups (P < 0.001 for both; Table 2). The partial eta-squared for the interaction effect was η²p = 0.135, representing a moderate-to-large effect size and underscoring a clinically meaningful enhancement in dynamic balance.

4.3. Lower Limb Strength

Repeated-measures ANOVA showed no significant main effect of group (P > 0.05), but both the main effect of time (P < 0.001) and the time × group interaction (P = 0.001) were highly significant. This indicates that the two interventions produced divergent improvements in lower extremity strength over time. Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons confirmed significant increases in strength from baseline to post-intervention in both groups (P < 0.001; Table 2). The partial eta-squared for the interaction was η²p = 0.304, reflecting a large effect size and substantial clinical improvement in lower extremity strength.

4.4. Functional Disability

Repeated-measures ANOVA demonstrated no significant main effect of group (P > 0.05); however, the main effect of time (P < 0.001) and the time × group interaction (P = 0.017) reached statistical significance. These results indicate differential reductions in functional disability between the DNS and DNSHS groups over the intervention period. Post-hoc Bonferroni tests showed significant decreases in RMDQ scores in both groups from pre- to post-intervention (P < 0.001; Table 2). The partial eta-squared for the interaction was η²p = 0.176, corresponding to a large effect size and clinically meaningful improvement in functional status.

| Variables | DNS a | DNSHS a | Factor | Group | Factor*Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | Change | Pre-test | Post-test | Change | ||||

| Balance (s) | 10.09 ± 1.10 | 9.27 ± 1.00 | 8.51↓ | 1.18 ± 0.70 | 8.77 ± 0.97 | 14.34↓ | F = 67.464; P < 0.001 b; ES = 0.692 | F = 0.441; P = 0.512; ES = 0.14 | F = 4.675; P = 0.039 b; ES = 0.135 |

| Strength (repeat) | 6.64 ± 1.07 | 8.97 ± 1.07 | 35.36↑ | 6.70 ± 1.30 | 10.00 ± 1.25 | 49.93↑ | F = 449.893; P < 0.001 b; ES = 0.937 | F = 1.870; P = 0.182; ES = 0.059 | F = 13.120; P < 0.001 b; ES = 0.304 |

| Disability (score) | 12.75 ± 1.87 | 8.18 ± 1.61 | 35.29↓ | 13.31 ± 1.95 | 6.00 ± 2.82 | 92.54↓ | F = 119.431; P < 0.001 b; ES = 0.799 | F = 1.607; P = 0.215; ES = 0.051 | F = 6.40; P = 0.017 b; ES = 0.176 |

Abbreviation: DNS, dynamic neuromuscular stabilization; DNSHS, hip-strengthening exercises.

a Values are expressed as Mean ± SD.

b Statistically significant.

5. Discussion

Non-specific chronic low back pain is highly prevalent among older women and adversely affects balance, lower extremity strength, and functional independence, ultimately diminishing quality of life. The present study demonstrates that an eight-week intervention combining dynamic neuromuscular DNS with targeted produces significantly greater improvements in dynamic balance, lower extremity strength, and functional disability compared with DNS alone.

Dynamic balance, as measured by the TUG test, improved significantly in both groups, but the DNSHS group exhibited substantially greater gains, with a statistically significant between-group difference. DNS enhances trunk stability through improved neuromuscular control of the core musculature, which reduces center-of-mass displacement during movement (19). However, the superior results in the DNSHS group underscore the pivotal role of gluteal strengthening. Weakness of the gluteus medius is associated with excessive lateral pelvic drop, which compromises balance (20), whereas targeted strengthening stabilizes the pelvis during transitional movements and walking phases of the TUG test. Similarly, enhanced gluteus maximus activation improves hip extension torque, facilitating faster sit-to-stand transitions and rapid stepping (21). These findings are consistent with previous reports that DNS improves dynamic balance and reduces fear of falling in older women (22, 23). Himmelreich et al. also noted that gluteal weakness is associated with compensatory patterns in low back pain, and its strengthening enhances lumbo-pelvic stability (24). Lee and Park demonstrated that lower limb strengthening exercises improve balance (25), while Jeong et al. found that combining gluteal and stabilization exercises yields greater benefits than stabilization exercises alone (26). The combination of DNS and gluteal exercises in the present study minimized trunk sway, reduced compensatory movements, and yielded markedly shorter TUG times compared with DNS alone.

Lower extremity strength, assessed using the 30-Second Chair Stand Test, also improved significantly in both groups, with the DNSHS group achieving superior results and a significant between-group difference. Although DNS activates deep stabilizers and facilitates force transfer to the lower limbs (27), it primarily targets postural control rather than prime movers such as the gluteus maximus and quadriceps. Consequently, strength gains in the DNS-only group were modest. In contrast, the DNSHS protocol directly targeted the gluteus maximus (the primary hip extensor) and gluteus medius, thereby enhancing pelvic control and minimizing compensatory knee valgus or lumbar substitution during the chair stand task (21). These findings are consistent with Rahimi et al., who reported that DNS exercises improve lower limb strength (28). Similarly, Nelson et al. demonstrated that specific strengthening exercises are more effective than general exercise interventions for improving strength in older adults (29). Lee and Park further showed that lower-limb strengthening enhances motor performance (25), whereas Jeong et al. found that integrating gluteal strengthening with stabilization exercises yields significantly greater strength improvements than stabilization training alone (26). Thus, the superior outcomes observed in the DNSHS group can be attributed to the synergistic effects of DNS, which improves core stability, and targeted gluteal strengthening, which optimizes lower-limb power generation.

Furthermore, the superior improvements observed in the DNSHS group can be attributed to complementary neuromuscular and biomechanical mechanisms. DNS promotes lumbopelvic stability by optimizing co-activation of the diaphragm, transversus abdominis, pelvic floor, and multifidus, which enhances postural control and efficient load transfer (30). However, DNS alone does not adequately address hip extensor weakness or frontal-plane pelvic instability commonly seen in chronic low back pain. Targeted strengthening of the gluteus medius reduces excessive lateral pelvic drop and compensatory lumbar side-bending (31), whereas enhanced gluteus maximus activation increases hip extension torque, thereby improving performance in functional tasks such as sit-to-stand transitions and stepping (32). Consistent with prior evidence, programs that integrate gluteal strengthening with stabilization exercises produce greater gains in motor performance and functional capacity than stabilization training alone (26). Thus, the synergistic combination of DNS and targeted gluteal strengthening in the present study resulted in more effective neuromuscular coordination and lumbopelvic stability, accounting for the markedly superior outcomes in the DNSHS group.

The results showed that both the DNS and DNSHS interventions significantly reduced functional disability in older women, as assessed by the RMDQ, with the DNSHS group demonstrating significantly greater improvement. The RMDQ measures low back pain-related disability, where lower scores indicate better mobility and fewer limitations in activities of daily living. The superior reduction in disability observed in the DNSHS group can be attributed to the complementary effects of DNS, which restores optimal movement patterns and spinal control, and targeted gluteal strengthening, which decreases biomechanical stress on the lumbar spine and pelvis. These findings align with Rahimi et al., who found that DNS exercises significantly reduce disability scores in older women (28). Similarly, Kooroshfard et al. reported that gluteal strengthening improves pelvic stability and indirectly reduces disability in individuals with chronic low back pain (33). Barghamadi et al. also demonstrated the efficacy of core stabilization exercises in decreasing disability among older women (34), while Stevens et al. showed that interventions combining muscle strengthening with stability training produce greater reductions in disability than stability training alone in patients with chronic low back pain (35).

This study has several limitations. The absence of a non-exercising control group precludes definitive conclusions about the absolute efficacy of the interventions. The 8-week duration is relatively short, and the lack of long-term follow-up limits insight into the sustainability of the observed benefits. The study was conducted exclusively in older women, which restricts generalizability to men or younger populations. Psychological factors were not assessed, potentially overlooking their influence on outcomes. Furthermore, the relatively small sample size further constrains the generalizability of the findings.

5.1. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that supplementing DNS with targeted DNSHS yields significantly greater improvements in dynamic balance, lower extremity strength, and functional disability than DNS alone in older women with chronic non-specific low back pain. The combined intervention optimizes both core stability and pelvic control, providing a more comprehensive rehabilitative approach. These findings indicate that clinicians should consider integrating specific gluteal strengthening exercises into DNS-based programs for older adults with chronic low back pain. This practical, evidence-based strategy can enhance functional outcomes, reduce disability, and ultimately improve mobility, stability, and quality of life in this population.