1. Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, accounting for a significant burden on healthcare systems (1). Despite advancements in medical and interventional therapies, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) continues to be a critical treatment modality for patients with complex multivessel disease or left main coronary artery involvement (2). The procedure has evolved over the decades, with improvements in surgical techniques, anesthesia management, and postoperative care, yet it is still associated with considerable risks and complications (3).

Demographic and clinical characteristics, such as age, gender, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia), and lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, obesity), significantly influence both the short- and long-term outcomes of CABG (4). For instance, older age and preexisting renal dysfunction are well-established predictors of postoperative complications, including acute kidney injury and mortality (5). Similarly, patients with poorly controlled diabetes or hypertension face higher risks of sternal wound infections and cardiovascular events (6).

The assessment of surgical outcomes is further complicated by the heterogeneity of patient populations and regional variations in risk factor prevalence (7). In Iran, CAD is a major public health concern, with rising incidence rates attributed to urbanization, sedentary lifestyles, and dietary changes (8). These factors are often intertwined with social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status and access to care.

While several studies have examined CABG outcomes in Western populations, data from Middle Eastern cohorts, particularly in Iran, remain limited (9). This gap underscores the need for region-specific research to guide clinical practice and improve patient care.

2. Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the demographic, clinical, and operative characteristics of patients undergoing CABG at a tertiary referral center in Iran, with a focus on postoperative complications such as mortality, renal failure, respiratory failure, and sternal infections. By identifying key risk factors and their associations with adverse outcomes, our findings may contribute to optimized preoperative risk stratification and tailored perioperative management. Furthermore, this research aligns with global efforts to enhance the quality of cardiac surgical care and reduce disparities in outcomes across different populations (10).

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted during 2024 at the Dr. Heshmat Educational and Therapeutic Hospital in Rasht, Iran, a referral center for cardiac surgeries. The study aimed to investigate the demographic, clinical, and postoperative outcomes of patients undergoing CABG.

A convenience sample of 379 patients meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled. The sample size was determined based on an expected complication rate of 30%, a confidence level of 95%, and a margin of error of 5%, yielding a minimum sample size of 323. We recruited 379 patients to enhance the robustness of the study.

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews and medical records, covering demographic details [age, gender, education, occupation, Body Mass Index (BMI)], clinical history [family history of coronary disease, previous myocardial infarction (MI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or CABG], comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, thyroid disorders, hyperlipidemia), lifestyle factors (smoking, drug use), and postoperative complications. Postoperative complications were defined using standardized criteria. Renal failure was defined according to kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) criteria as an increase in serum creatinine by ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours or an increase to ≥ 1.5 times the baseline value within the first 7 postoperative days. Respiratory failure was defined as the requirement for mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours postoperatively or the need for re-intubation. Life-threatening arrhythmias were defined as new-onset atrial fibrillation/flutter, sustained ventricular tachycardia, or advanced heart block requiring pharmacological or electrical intervention. Hepatic failure was defined as a serum bilirubin level exceeding 2.0 mg/dL accompanied by an international normalized ratio (INR) greater than 1.5 in the absence of anticoagulant therapy. A sternal wound infection was defined based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria for surgical site infection. Mortality was defined as all-cause death occurring during the hospital stay or within 30 days of the surgery.

All patients underwent on-pump CABG using a standard protocol. The mean cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time was 85.2 ± 18.5 minutes, and the mean aortic cross-clamp time was 54.7 ± 14.3 minutes. Perioperative medication management, including beta-blockers for arrhythmia prophylaxis, was administered according to institutional guidelines based on prevailing standards of care. The CPB protocol involved a membrane oxygenator, non-pulsatile flow maintained at 2.4 L/min/m2, and mild systemic hypothermia (32 - 34°C). Myocardial protection was achieved using intermittent cold blood cardioplegia.

3.2. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 21. Descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables, frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were used to summarize patient characteristics. The normality of continuous variables (age, BMI) was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

For univariate analysis, chi-square tests were used for categorical variables, and independent samples t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests were used for continuous variables, as appropriate, to compare groups with and without complications.

A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to identify independent predictors of the composite postoperative complication endpoint. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

This cross-sectional study, titled "Demographic and Clinical Predictors of Postoperative Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting", was conducted in accordance with international ethical standards. The study protocol received formal approval from the Institutional Review Board of Guilan University of Medical Sciences (approval code: IR.GUMS.REC.1403.456) prior to study initiation. Our sample included patients from various socioeconomic and residential backgrounds, including farmers and workers, reflecting a segment of the rural and disadvantaged population.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

The study included 261 (68.9%) male and 118 (31.1%) female patients, with a mean age of 60.37 ± 7.37 years. The majority of patients (87.6%) were classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status II. The detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 261 (68.9) |

| Female | 118 (31.1) |

| Age (y) | |

| < 65 | 272 (71.8) |

| ≥ 65 | 107 (28.2) |

| Mean ± SD (min - max) | 60.37 ± 7.37 (38 - 80) |

| Education level | |

| Illiterate/primary | 76 (20.1) |

| Below diploma | 114 (30.1) |

| Diploma | 145 (38.3) |

| University | 44 (11.6) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed/housewife/retired | 132 (34.8) |

| Employee | 76 (20.1) |

| Farmer/laborer | 64 (16.9) |

| Self-employed | 107 (28.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| < 25 | 125 (33.0) |

| 25 - 30 | 184 (48.5) |

| ≥ 30 | 70 (18.5) |

| Mean ± SD (min - max) | 26.7 ± 3.22 (20.24 - 33.15) |

| ASA class | |

| II | 332 (87.6) |

| III | 47 (12.4) |

| EF (%) | |

| < 45 | 148 (39.1) |

| ≥ 45 | 231 (60.9) |

| Mean ± SD (min - max) | 44.23 ± 9.07 (20 - 60) |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless indicated.

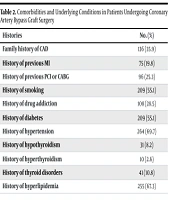

Hypertension (69.7%) and hyperlipidemia (67.3%) were the most prevalent comorbidities, followed by diabetes mellitus (55.1%). A history of smoking was reported by 55.1% of patients, and 28.5% had a history of substance abuse. A family history of CAD was present in 35.9% of patients, while 19.8% had a previous MI, and 25.3% had undergone prior PCI or CABG. These data are presented in Table 2. The mean CPB time was 85.2 ± 18.5 minutes, and the mean aortic cross-clamp time was 54.7 ± 14.3 minutes.

| Histories | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Family history of CAD | 136 (35.9) |

| History of previous MI | 75 (19.8) |

| History of previous PCI or CABG | 96 (25.3) |

| History of smoking | 209 (55.1) |

| History of drug addiction | 108 (28.5) |

| History of diabetes | 209 (55.1) |

| History of hypertension | 264 (69.7) |

| History of hypothyroidism | 31 (8.2) |

| History of hyperthyroidism | 10 (2.6) |

| History of thyroid disorders | 41 (10.8) |

| History of hyperlipidemia | 255 (67.3) |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

Overall, 133 patients (35.1%) experienced at least one postoperative complication. The most frequent complication was life-threatening arrhythmias (21.4%), followed by respiratory failure (6.1%), renal failure (5.5%), hepatic failure (3.7%), and sternal wound infection (2.6%). No redo-CABG procedures were recorded during the study period. The 30-day mortality rate was 1.6% (6 patients). The frequency of complications is detailed in Table 3.

| Surgical Outcomes | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Kidney failure | 21 (5.5) |

| Respiratory failure | 23 (6.1) |

| Liver failure | 14 (3.7) |

| Life-threatening arrhythmias | 81 (21.4) |

| Sternal wound infection | 10 (2.6) |

| Redo CABG | 0 (0) |

| Mortality (death during or within 30 days post-operation) | 6 (1.6) |

Abbreviation: CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

The analysis of associations between preoperative factors and the occurrence of any postoperative complication revealed a single, highly significant relationship. A history of previous MI was strongly associated with a higher incidence of complications (P < 0.001). When comparing the group with complications to the group without complications, there were no significant differences in mean age (61.1 ± 7.1 vs. 60.0 ± 7.5 years, P = 0.15, independent samples t-test) or mean BMI (26.9 ± 3.4 vs. 26.6 ± 3.1 kg/m2, P = 0.38, independent samples t-test). Other factors, including family history of CAD, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, and substance abuse, did not show a statistically significant association with the composite complication endpoint. These results are shown in Table 4.

| Variables | With Complications (N = 133) | Without Complications (N = 246) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family history of CAD | 0.237 | ||

| Yes | 53 (39.8) | 83 (33.7) | |

| No | 80 (60.2) | 163 (66.3) | |

| History of previous MI | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 43 (32.3) | 32 (13.0) | |

| No | 90 (67.7) | 214 (87.0) | |

| History of PCI or CABG | 0.746 | ||

| Yes | 35 (26.3) | 61 (24.8) | |

| No | 98 (73.7) | 185 (75.2) | |

| Smoking history | 0.469 | ||

| Yes | 70 (52.6) | 139 (56.5) | |

| No | 63 (47.4) | 107 (43.5) | |

| History of substance abuse | 0.352 | ||

| Yes | 34 (25.6) | 74 (30.1) | |

| No | 99 (74.4) | 172 (69.9) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.887 | ||

| Yes | 74 (55.6) | 135 (54.9) | |

| No | 59 (44.4) | 111 (45.1) | |

| Hypertension | 0.210 | ||

| Yes | 98 (73.7) | 166 (67.5) | |

| No | 35 (26.3) | 80 (32.5) | |

| Thyroid disorders | 0.365 | ||

| Yes | 17 (12.8) | 24 (9.8) | |

| No | 116 (87.2) | 222 (90.2) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.135 | ||

| Yes | 96 (72.2) | 159 (64.6) | |

| No | 37 (27.8) | 87 (35.4) |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Chi-square test was used.

c A significant association (P < 0.001) was found between a history of previous MI and the incidence of post-CABG complications.

A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed, including history of previous MI, age, gender, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking history. The model confirmed that a history of previous MI was an independent predictor of postoperative complications [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.95, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.68 - 5.18, P < 0.001]. None of the other variables included in the model reached statistical significance as independent predictors.

Analysis of 30-day mortality showed no statistically significant associations with any of the preoperative risk factors studied, including history of MI, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or smoking habits (all P-values > 0.05). However, it is crucial to note that the very low number of mortality events (n = 6) severely limits the statistical power and reliability of any association tested for this outcome. The results for mortality are summarized in Table 5.

| Variables | With Mortality (N = 6) | Without Mortality (N = 373) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family history of CAD | 0.426 | ||

| Present | 1 (16.7) | 135 (36.2) | |

| Absent | 5 (83.3) | 238 (63.8) | |

| History of previous MI | 0.339 | ||

| Present | 2 (33.3) | 73 (19.6) | |

| Absent | 4 (66.7) | 300 (80.4) | |

| History of PCI or CABG | 0.623 | ||

| Present | 1 (16.7) | 95 (25.5) | |

| Absent | 5 (83.3) | 278 (74.5) | |

| Smoking history | 0.798 | ||

| Present | 3 (50.0) | 206 (55.2) | |

| Absent | 3 (50.0) | 167 (44.8) | |

| History of substance abuse | 0.189 | ||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 108 (29.0) | |

| Absent | 6 (100.0) | 265 (71.0) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.798 | ||

| Present | 3 (50.0) | 206 (55.2) | |

| Absent | 3 (50.0) | 167 (44.8) | |

| Hypertension | 0.872 | ||

| Present | 4 (66.7) | 260 (69.7) | |

| Absent | 2 (33.3) | 113 (30.3) | |

| Thyroid disorders | 0.390 | ||

| Present | 0 (0.0) | 41 (11.0) | |

| Absent | 6 (100.0) | 332 (89.0) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.183 | ||

| Present | 6 (100.0) | 249 (66.8) | |

| Absent | 0 (0.0) | 124 (33.2) |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary interventional; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Chi-square test was used.

c No statistically significant associations were found between the studied risk factors and post-CABG mortality.

No significant associations were found between education level (P = 0.451) or occupation (P = 0.387) and the composite complication endpoint in this cohort. Similarly, no significant association was found between these socioeconomic proxies and mortality (P > 0.05).

5. Discussion

The CABG remains a cornerstone in the management of severe CAD, offering significant improvements in survival and quality of life. This study, conducted at Dr. Heshmat Hospital in Rasht, Iran, provides valuable insights into the demographic, clinical, and outcome characteristics of patients undergoing CABG in 2023 - 2024. The findings align with and expand upon existing literature while highlighting unique regional trends and challenges.

The study cohort comprised 379 patients, with a male predominance (68.9%), consistent with global data indicating higher CAD prevalence in males due to hormonal and lifestyle factors (11). The mean age of 60.37 years reflects the typical age range for CABG candidates, though the inclusion of younger patients (< 65 years, 71.8%) suggests an emerging trend of premature CAD in Iran, possibly linked to urbanization, sedentary lifestyles, and dietary shifts (12). This very high prevalence represents an alarming disease burden at the population level, underscoring an urgent need for strengthened primary and secondary prevention programs targeting metabolic risk factors in Iran. These rates exceed those reported in Western cohorts, emphasizing the need for aggressive risk factor management in Middle Eastern populations (13).

The mortality rate in this study was 1.6%, lower than rates reported in similar settings. This may reflect advancements in perioperative care, including improved anesthetic techniques and postoperative monitoring. However, complications such as renal failure (5.5%), respiratory failure (6.1%), and arrhythmias (21.4%) were observed, consistent with global CABG outcome studies (14).

Life-threatening arrhythmias occurred in 21.4% of patients in this study, consistent with the findings of Biancari et al. in Validation of EuroSCORE II (15), where postoperative arrhythmias were reported in 18 - 25% of cases. The significant association between prior MI and arrhythmias (P = 0.002) in this study underscores the importance of preoperative cardiac evaluation, as emphasized by Neumann et al. (2). This study identified higher BMI and ASA class III as significant predictors (P = 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively), aligning with the findings of Ghanta et al., who highlighted obesity as a risk factor for prolonged mechanical ventilation (4). The renal failure rate of 5.5% in this study is similar to the 4 - 7% reported by Welz et al. (5). The association between renal failure and ASA class III (P < 0.001) reinforces the prognostic value of ASA classification, as noted by Davenport et al. (16). Sternal wound infections occurred in 2.6% of patients, consistent with the 2 - 4% range reported by Williams et al. (6). The absence of redo-CABG cases contrasts with rates of 1 - 4% in other studies, possibly due to the study's short follow-up period (30 days) (17, 18).

Key predictors of adverse outcomes included ASA class III, which was correlated with renal and respiratory failure, reinforcing the prognostic value of the ASA classification (16). Additionally, prior MI and hyperlipidemia were linked to arrhythmias and hepatic dysfunction, respectively, underscoring the importance of preoperative optimization (15).

The high prevalence of hypertension (69.7%) and diabetes mellitus (55.1%) in this cohort exceeds rates in European registries (e.g., 50% hypertension, 30% diabetes mellitus) but parallels data from South Asia, where metabolic risk factors are prevalent (19). The 28.5% rate of substance abuse (e.g., smoking, opioids) is notably higher than in Western cohorts, suggesting cultural and socioeconomic influences on CAD risk (20). This high rate represents a serious public health issue. Integrating harm reduction strategies and referrals to community-based substance treatment programs into preoperative care could be a vital preventive measure to improve surgical outcomes and overall community health.

A key finding of our study was that, in univariate analysis, only a history of previous MI was significantly associated with the composite postoperative complication endpoint, while other established risk factors like diabetes mellitus and hypertension were not. This finding could be attributed to several factors. First, the perioperative management at our center, which includes standardized protocols for glycemic control and blood pressure management, may have mitigated the expected impact of these comorbidities on short-term outcomes. Second, the cross-sectional design and sample size, while adequate for detecting a strong effect like that of previous MI, may have provided insufficient statistical power to detect more modest associations for other variables. This is a known limitation of studies with a fixed sample size when the event rate for the outcome (complications = 35.1%) and the prevalence of some risk factors is not extreme.

The multivariable analysis confirmed the independent role of previous MI, suggesting its effect is robust even when considering other variables. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension were controlled for in the multivariable logistic regression model. The model included history of previous MI, age, gender, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and smoking history. Despite this adjustment, only previous MI remained a significant predictor. We conducted post-hoc analyses to test for interaction effects between previous MI and both diabetes mellitus and hypertension in relation to the complication outcome. However, interactions were not statistically significant (P for interaction > 0.10 for both), suggesting that the effect of previous MI on complications was not significantly modified by the presence of either diabetes mellitus or hypertension in our cohort. The absence of significant association for diabetes mellitus and hypertension in our analysis likely reflects the complex interplay of effective clinical management and the predominant strength of the prior MI effect, rather than a true lack of biological relevance.

Furthermore, our exploratory analysis did not find significant associations between socioeconomic proxies (education, occupation) and complications in this dataset. However, the absence of data on other system-level factors like distance to healthcare, insurance coverage, and pre-surgical management of chronic diseases limits our ability to fully explore health inequalities, an important area for future research.

While this study is single-center, which may limit statistical generalizability, the detailed description of our patient population and context enhances the transferability of findings to other similar settings in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region that share comparable sociodemographic and clinical profiles.

These findings have important implications for clinical practice. Preoperative optimization, including rigorous control of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, could mitigate complications, and programs targeting smoking cessation and weight loss should be prioritized (21). High-risk patients (e.g., ASA class III, BMI > 30) may benefit from extended intensive care unit stays and advanced hemodynamic monitoring (22, 23).

From a health systems perspective, our findings suggest several specific recommendations: (1) Enhanced screening and management of patients with a history of MI at the primary care level to ensure optimal medical therapy and timely referral; (2) consideration of establishing specialized preoperative clinics for comprehensive risk assessment and management, particularly for high-risk subgroups; (3) fostering a multidisciplinary care team that includes public health experts, psychologists, and social workers to address the complex bio-psycho-social needs of these patients, including substance abuse and socioeconomic challenges. Additionally, the unique risk profile of this population warrants region-specific CABG protocols, emphasizing metabolic management.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the interplay of demographic and metabolic factors in CABG outcomes in Iran. While mortality rates are favorable, complications remain significant, calling for targeted interventions. The strong, independent association of previous MI with postoperative complications underscores its importance in preoperative risk assessment. This finding should directly inform clinical practice to prioritize these patients for intensive optimization. Future research should explore longer-term outcomes such as return to work, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and the economic burden of the disease for the patient and family.

5.2. Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. Its single-center design may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings in Iran or other countries. The 30-day follow-up period precludes assessment of long-term outcomes such as graft patency and late complications.

Furthermore, the focus on short-term physical complications means longer-term outcomes crucial from a health perspective, such as return to work, HRQoL, and economic burden, were not addressed.

Furthermore, the low number of mortality events (n = 6) severely limited the statistical power to identify predictors of mortality, making a meaningful analysis for this specific outcome unfeasible. The use of arbitrary categories for continuous variables like BMI is another limitation; future studies could benefit from using continuous models or validated cut-off points. Finally, while we employed multivariable regression, the possibility of unmeasured confounding factors cannot be entirely ruled out. The absence of data on system-level factors limits the exploration of broader health determinants.