1. Background

The maxillary sinus is the first paranasal sinus to develop, and its growth is completed by the eruption of the maxillary third molar around the age of 20 years (1). A computed tomography (CT) study reported that maxillary sinus growth continues into the third decade of life in males and into the second decade in females (2). Although the maxillary sinus is usually bilaterally symmetrical, there are considerable individual differences in its size and shape (3).

The maxillary sinus floor (MSF) is formed by the alveolar processes of the maxilla and is located about 5 mm below the nasal cavity floor at the age of 20 years (4). The posterior maxillary teeth have close anatomical proximity to the MSF, and factors such as ethnicity, sex, age, side, and presence or absence of adjacent teeth may influence the average distance between the root apex and MSF (5). During the normal eruption of molars, the sinus floor moves occlusally and surrounds the root apices of the first premolars to the third molars (PMRs).

Alveolar height, like the distance between MSF and PMRs, decreases with increasing age (6, 7). Due to the anatomical proximity of the posterior maxillary roots to the MSF, dental infection may spread into the maxillary sinus (MS) through periapical tissues, causing odontogenic maxillary sinusitis, which accounts for 10 - 12% of all sinusitis cases (8). The closeness of posterior tooth apices to the maxillary sinus is mainly a concern for treatments in this area. Extrusion of endodontic instruments beyond the apex, apical surgery, extraction of retained roots, and maxillary sinus surgeries in the presence of teeth or dental implants highlight the importance of understanding the anatomy of this region (9).

An oroantral communication (OAC) may occur following extraction or surgical removal of maxillary molars due to the proximity between the roots and the MSF. The most common site of OAC is the maxillary first molar, followed by the second and third molars (10, 11). Other reported complications include: (A) orbital abscess due to odontogenic infection, (B) spread of infection from a periodontal pocket to the adjacent maxillary sinus, and (C) risk of root canal materials entering the sinus cavity (12-16). If clinical errors occur during root canal treatment, shaping instruments, irrigation solutions, and filling materials may be extruded into the maxillary sinus (17). These situations can lead to complications such as odontogenic sinusitis, oroantral syndrome, and traumatic changes, which pose complex problems for dentists (18).

Only a thin mucosal or cortical bone layer exists in the MSF, which increases the risk of oroantral fistula or sinus infection (19, 20). Therefore, the simplest method to assess the relationship between the MSF and PMRs involves appropriate imaging of this area. Periapical and panoramic radiographs are conventional imaging techniques used to plan treatment and evaluate the proximity of roots to the MSF. However, they only provide two-dimensional images, which cause superimposition and magnification of anatomical structures. During periapical surgery, two-dimensional radiographs cannot determine the risk of MSF perforation (21). In general, panoramic radiography is considered an unreliable method for determining the topographic relationship between posterior teeth and the maxillary sinus (22, 23).

The advent of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) has provided accurate three-dimensional imaging of hard tissues at a reasonable cost, revolutionizing imaging of the maxillofacial structures (24). CBCT was introduced in 1998, and its clinical and research applications in dentistry are increasing daily.

Studies using CBCT have shown that the distance between posterior tooth apices and the MSF increases with age, and that premolars in males are generally closer to the sinus compared to females. Several CBCT studies in different populations have examined the influence of age, sex, and adjacent teeth on the relationship between posterior teeth and the sinus floor. Pei et al. reported that the distance between posterior tooth apices and the MSF increases with age, and premolars in males are generally closer to the sinus than in females (25). Estrela et al. found that molar roots are closer to the sinus floor compared to premolars (19). Similar findings regarding age, sex, and root-specific variations were reported by Ragab et al., Ok et al., Tian et al., and Gu et al. (5, 26-31). These studies highlight that anatomical variations differ across populations and emphasize the importance of population-specific data.

The CBCT provides isotropic three-dimensional information with lower dose and cost, and it shows the maxillary sinus and related structures with higher quality compared to CT, with growing accessibility (26). The lack of geometric distortion and prevention of superimposition of adjacent structures are other advantages, making CBCT a precise and non-invasive method for evaluating the relationship between posterior tooth apices and the MSF (24, 27).

2. Objectives

The posterior maxillary teeth, compared to other teeth, exhibit complex anatomical features and a close relationship with the maxillary sinus. Although several studies have investigated these relationships in various populations, limited data are available regarding the Iranian population, particularly in Zahedan. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the spatial relationship between the apices of posterior maxillary teeth and the MSF in the Zahedan population using CBCT. The findings of this study are expected to provide valuable reference data for clinical procedures such as root canal treatment, tooth extraction, dental implant placement, and other interventions in this region.

3. Methods

This descriptive-analytical study was conducted in 2023 at Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, after the research proposal was approved by the Research Council of the Faculty of Dentistry and permission was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. Initially, 90 CBCT scan samples of patients from the Radiology Department of the Faculty of Dentistry were selected by a student, and then reconstructed cross-sectional slices, starting from the anterior region and serially, were examined with the assistance of a radiology specialist. The obtained information was recorded in an information form. Finally, the data were coded and entered into SPSS version 19 software.

4. Results

In this study, the relationship between the position of posterior tooth apices and the sinus floor was classified into three categories: Extra-sinus (OS), in contact with the sinus (TS), and intra-sinus (IS).

A total of 90 CBCT images were evaluated in terms of the relationship between the apices of the maxillary molars and the MSF. The mean age of the samples was 26.8 ± 5.7 years, ranging from 18 to 46 years. Regarding age distribution, 60 participants (66.6%) were under 25 years, and 30 participants (33.4%) were over 25 years. In terms of gender distribution, 14 participants (15.5%) were male, and 76 participants (84.5%) were female.

Since in this study the position and relationship between the apices of maxillary molar teeth and the sinus floor were evaluated for the roots of the examined teeth — namely, the first premolar, second premolar, first molar, and second molar — the units of investigation were considered as individual roots: Palatal and buccal roots in premolars, and palatal, distobuccal, and mesiobuccal roots in molars, on both left and right sides, resulting in a total of 1,307 cases.

The first premolar is almost always OS. The second premolar is most often seen in contact with or OS. Molars (first and second) show the greatest variation, with intra-sinus cases more frequently observed in the distobuccal and palatal roots (Table 1).

| Tooth type / Root | OS | TS | IS |

|---|---|---|---|

| First premolar – buccal | 98.5 | 1.5 | 0 |

| First premolar – palatal | 96.3 | 3.7 | 0 |

| Second premolar | 48.5 | 51.5 | 0 |

| First molar – mesio buccal | 64.7 | 35.2 | 0 |

| First molar – disto buccal | 38.6 | 44.1 | 17.6 |

| First molar – palatal | 32.6 | 45.9 | 21.6 |

| Second molar – mesio buccal | 26.2 | 49.1 | 24.7 |

| Second molar – disto buccal | 35.2 | 61.4 | 3.3 |

| Second molar – palatal | 41.6 | 46.5 | 2.6 |

Abbreviations: OS, extra-sinus; TS, in contact with the sinus; IS, intra-sinus.

a Values are presented as No. (%).

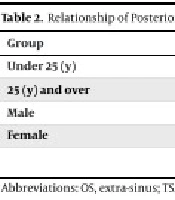

In individuals under 25 years, most roots were extra-sinus, while in those 25 years and older, roots were more frequently in contact with the sinus. In males, the percentage of extra-sinus roots was slightly higher, whereas in females, contact with the sinus was more common (Table 2).

| Groups | OS | TS | IS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under 25 years | 63.1 | 29.2 | 7.7 |

| 25 years and over | 44.7 | 47.8 | 7.5 |

| Male | 56.8 | 36.6 | 6.6 |

| Female | 50.5 | 43.7 | 5.8 |

Abbreviations: OS, extra-sinus; TS, in contact with the sinus; IS, intra- sinus.

a Values are presented as No. (%).

5. Discussion

Pei et al., in a study aimed at determining the relationship between the roots of maxillary posterior molars and the sinus floor using CBCT images in a Western Chinese population, reported that the distance between molar apices and the maxillary sinus increases with age, and that premolars in men were closer to the sinus compared to women (25).

In the present study, in 98% of males and 95.8% of females, the buccal root of the first maxillary premolar was of the OS type, while in the palatal root, 97.1% of males and 98% of females also showed OS type. Fisher’s exact test showed no significant difference in the distribution of root apex position of first maxillary premolars in relation to the sinus floor by sex. On the other hand, in the distobuccal root of the first molar, the most common relationship was TS in both males (89.2%) and females (54.4%), and this difference was statistically significant using the chi-square test. In the palatal root, most relationships were TS in females (94.5%) and OS in males (47%). In the mesiobuccal root, most relationships in both men and women were OS type, though the differences were not statistically significant These findings were consistent with the study of Ragab et al. (26), but not with Johari et al. (27). Such discrepancies may be due to differences in population distribution, timing, setting, and sample size.

Estrela et al., in a Brazilian CBCT study, reported that maxillary molar roots are closer to the sinus floor compared to premolars (19). In the present study as well, in the distobuccal, mesiobuccal, and palatal roots of the first molar, most cases under 25 years showed TS type, whereas in those over 25 years, most cases were OS type. This difference was statistically significant, indicating that distribution by age influences the relationship. These results are partially consistent with studies by Ok et al. in Turkey (28) and Pei et al. in China (25).

Among the studied variables were age and sex. According to the results, the pattern of maxillary sinus development differs across ages, sexes, and populations. Langford et al. (29) reported that the extent and nature of sinus growth vary significantly by age. Although the present study included only subjects 18 years and older to exclude changes during sinus development, age still showed an effect on the anatomical variation and positional relationship of molar apices with the sinus floor.

With respect to sex, differences in root apex position were observed. This may be explained by the fact that men generally have longer, more extensive, and fully developed roots, along with larger bone mass and volume, justifying the differences observed here.

Age analysis showed that in some teeth and roots, age influenced the relationship between molar apices and the sinus floor. Previous studies have provided limited data on this correlation. von Arx et al. (30) found no effect of age on MSF relationships, which contrasts with our findings. Conversely, Tian et al. (31) showed that the mean distance between MSF and posterior molar roots decreases with age in a Chinese population. Gu et al. (5) also found that, in all posterior roots, the distance between the apex and MSF increases with age.

Regarding the effect of missing adjacent teeth: For the first premolars, both when no adjacent teeth were missing and when one tooth was missing, most cases were OS type (97.6% and 94.5%, respectively). For the second premolars, when no adjacent teeth were missing, most cases were TS type (56.3%), while when one tooth was missing, most cases were OS type (66.3%). A significant relationship was found between the status of adjacent tooth loss and the type of relationship with the sinus floor for premolars. For first and second molars, in both cases with and without adjacent missing teeth, most relationships were of the TS type (97.6% and 94.5%, respectively). The chi-square test confirmed that adjacent tooth loss significantly influenced the type of relationship in first and second molars across all three roots. This partially agrees with Pei et al. (25), although there are few comparable studies in this regard. Nevertheless, the role of adjacent tooth loss should be considered in diagnosis and treatment planning.

Overall, this study demonstrated that the anatomical variation and position of posterior maxillary tooth apices relative to the sinus floor depend on age, sex, geographic region, and measurement method. In second premolars, the position depended on sex, with TS more common in females and OS more common in males. In first and second molars, the position was more age-dependent, with a tendency toward OS type as age increased. Regarding adjacent tooth loss, in second premolars and molars, missing adjacent teeth shifted the position toward OS type.

5.1. Conclusions

Age and sex play a determining role in the position of maxillary molar apices relative to the maxillary sinus floor. This relationship varies by tooth type, root type, and presence or absence of adjacent teeth. In second molars, OS type was more frequent in males, while in females TS type was more frequent. In individuals under 25 years, most cases were TS, while in those over 25 years, most cases were OS. Similarly, in first molar roots (distobuccal, mesiobuccal, palatal), TS type predominated under 25 years, whereas OS predominated above 25 years. Adjacent tooth loss also influenced the relationship: In first premolars, most cases remained OS regardless of adjacent tooth loss, whereas in second premolars, the pattern shifted from TS to OS with tooth loss. In molars, TS predominated in both cases.

Given this anatomical variability, clinicians in this region should take into account age, sex, tooth type, and root type in diagnostic and interventional procedures.