1. Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged in December 2019 and rapidly evolved into a global pandemic, overwhelming healthcare systems and causing significant morbidity and mortality (1, 2). While early data suggested children were less affected than adults (3), subsequent studies confirmed pediatric susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, albeit with a higher prevalence of asymptomatic or mild cases (4-6). Global analyses indicate lower fatality rates in children, with no deaths reported in those under 9 years and rates of 0.2 - 0.4% in adolescents (7). Pediatric cases constitute 1.2 - 2% of total COVID-19 infections, with severe/critical disease occurring in approximately 5% and 0.6% of cases, respectively (8-11). However, children with pre-existing chronic conditions face elevated risks of severe outcomes (12).

In Iran, studies report a 5.3% mortality rate among hospitalized pediatric COVID-19 patients, rising to 14.4% in those with comorbidities (13, 14). Risk factors for poor outcomes include dyspnea, infancy (< 1 year), comorbidities, and lower Body Mass Index (BMI) (13-15). Although acute manifestations like pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multi-organ dysfunction (e.g., myocarditis, kidney injury) are rare, they necessitate intensive care unit (ICU) in severe cases (3, 16-19). Non-respiratory manifestations, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, ocular issues [e.g., conjunctivitis in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)], and hematological abnormalities, have also been documented (18-20).

Emerging evidence highlights long-term sequelae (“long COVID”) in children, including persistent fatigue, cognitive difficulties, and cardiopulmonary or neurological symptoms, even after mild acute illness (21-26). Hospitalized children are particularly vulnerable to prolonged health impacts (27). Despite growing recognition, current literature on pediatric COVID-19 manifestations remains limited and heterogeneous in study designs, follow-up durations, and outcome measures. This gap hinders the development of standardized management protocols.

Clarifying the association between initial disease severity and subsequent manifestations is vital for creating risk stratification protocols, enabling healthcare providers to prioritize follow-up care for children at the highest risk for prolonged illness. Additionally, understanding the recovery trajectories and long-term burden of COVID-19 in hospitalized children is essential for optimizing post-discharge resource allocation and developing effective preventive strategies to mitigate chronic morbidity.

2. Objectives

This study investigates short- and long-term manifestations in hospitalized children with COVID-19, stratified by disease severity, to inform clinical decision-making and preventive strategies. By analyzing outcomes in 295 pediatric patients from Tehran, we aim to clarify associations between disease severity, manifestations, and recovery trajectories. These insights will guide risk stratification, optimize resource allocation, and improve post-discharge care for this population.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This retrospective cross-sectional study analyzed short- and long-term manifestations in hospitalized pediatric COVID-19 patients based on disease severity.

1. Inclusion criteria:

- Hospitalized patients aged < 18 years.

- Admission to either Bahrami Children Hospital or Baqiyatullah Hospital between March 2021 and April 2022.

- Confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis, defined as a positive nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test and clinical symptoms consistent with COVID-19 (e.g., fever, cough, respiratory distress, gastrointestinal symptoms).

2. Exclusion criteria:

- Patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 but were admitted for an unrelated medical condition (e.g., trauma, elective surgery) and had no active COVID-19 symptoms.

- Patients or families who declined participation in the research.

- Patients lost to follow-up for both short-term and long-term outcome data.

Ethical approval was obtained (IR.BMSU.BAQ.REC.1402.008). Diagnoses required a positive nasopharyngeal PCR test and clinical symptoms. Patients were stratified into mild, moderate, severe, or critical categories using criteria for clinical management of COVID-19 (28):

1. Mild: Upper respiratory symptoms (e.g., fever, cough) without hypoxia.

2. Moderate: Lower respiratory infection, pneumonia (SpO2 ≥ 90%).

3. Severe/critical: Pneumonia with hypoxemia (SpO2 < 90%), respiratory distress, ARDS, or critical systemic involvement requiring mechanical ventilation.

3.2. Data Collection and Definitions

Demographics, comorbidities, symptoms, manifestations, and outcomes were extracted from hospital registries (objective data such as documentation of practitioner visits and paraclinical data). Identification of long-term manifestations (at 12 weeks) was achieved through a retrospective review of hospital records for readmissions and outpatient visits, supplemented by structured telephone interviews conducted at the 12-week endpoint.

Primary endpoints included organ-specific manifestations (respiratory, hematological, renal, etc.) categorized as short-term (≤ 2 weeks post-onset) or long-term (≤ 12 weeks), aligned with Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) and the World Health Organization (WHO)'s clinical case definition for post-COVID-19 condition (U09.9). Specific definitions included:

1. Respiratory: SpO2 < 92%, tachypnea (age-adjusted thresholds), or respiratory acidosis.

2. Hematological: Leukopenia, leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, or thrombocytosis.

3. Renal: Oliguria (for infants < 1 mL/kg/h, for children < 0.5 mL/kg/h), elevated creatinine, elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN), or pyuria.

4. General: Weight loss (> 1 standard deviation for age), anemia, fatigue (child prevented from performing normal daily activities, unable to attend school, struggles to get out of bed, or has significant functional impairment), and sleep disturbance (measured based on patient self-report).

The absence of objective assessment methods limits both the clinical relevance and interpretability of the findings. All reference ranges were from the laboratory reference range according to the Harriet Lane reference range (version 15, chapter 27), and thus have been adjusted for children (29).

Secondary endpoints included diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), MIS-C, ICU admission, hospitalization duration, readmission, and mortality.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized demographics and clinical features. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies (%), and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (normality confirmed via Kolmogorov-Smirnov/Shapiro-Wilk tests). Associations between disease severity and manifestations were assessed using chi-square, Fisher’s exact, or analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests. Variables with significant univariable relationships (P < 0.05) underwent multivariable logistic regression. Analyses were performed in IBM SPSS v26, with significance set at P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Characteristics

Of 320 initially enrolled patients, 25 lost to follow-up were excluded, yielding a final cohort of 295. Thus, the study included 295 hospitalized children (40.3% female; mean age 3.04 ± 2.98 years) with PCR-confirmed COVID-19. Disease severity was mild (67.5%, n = 199), moderate (27.1%, n = 80), or severe/critical (5.4%, n = 16). The mortality rate was 1.01% (3 deaths among 295 cases). Common comorbidities included neurological (8.47%), pulmonary (6.44%), and congenital metabolic disorders (5.08%). Univariable analysis linked diabetes, pulmonary disease, and immune disorders to severity (P < 0.001), but multivariable analysis showed no significant associations (P > 0.05, Table 1).

| Variables | All Patients (N = 295) | Univariant/Multivariant P-Value | Patients with Mild COVID-19 (N = 199) | Patients with Moderate COVID-19 (N = 80) | Patients with Severe/Critical COVID-19 (N = 16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 3.04 ± 2.98 | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 2.84 ± 3.05 | 2.71 ± 3.26 | 4.60 ± 3 |

| Sex (female) | 119 (40.3) | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 87 (44) | 24 (30) | 8 (50) |

| Weight (kg) | 13.35 ± 7.73 | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 13.45 ± 7.47 | 12.39 ± 8.44 | 16.9 ± 8.59 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 10 (3.38) | < 0.001/> 0.05 | 3 (1.50) | 2 (2.50) | 5 (31.25) |

| Cardiovascular diseases (%) | 4 (1.35) | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 2 (1.00) | 2 (2.50) | - |

| Pulmonary (%) | 19 (6.44) | < 0.001/> 0.05 | 5 (2.50) | 7 (8.75) | 7 (43.75) |

| Hepatic (%) | 4 (1.35) | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 3 (1.50) | - | 1 (6.25) |

| Renal (%) | 6 (2.03) | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 5 (1.69) | - | 1 (6.25) |

| Gastrointestinal (%) | 8 (2.71) | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 5 (2.51) | 3 (3.75) | - |

| Neurological (%) | 25 (8.47) | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 18 (9.04) | 4 (5.00) | 3 (18.75) |

| Immune def. (%) | 5 (1.69) | < 0.001/> 0.05 | 1 (0.50) | - | 4 (25.00) |

| Congenital metabolic (%) | 15 (5.08) | > 0.05/> 0.05 | 9 (4.52) | 4 (5.00) | 2 (12.5) |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b No significant differences between groups

4.2. Presenting Symptoms

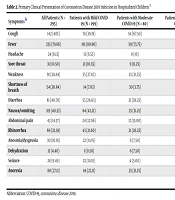

Fever (79.66%), cough (48.13%), diarrhea (40.70%), and nausea/vomiting (40.33%) were most frequent (Table 2). Severe disease correlated with cough, weakness, dyspnea, abdominal pain, dehydration, and anorexia in univariable analysis (P < 0.05). However, multivariable analysis retained only cough (P = 0.01), dyspnea (P < 0.001), and dehydration (P < 0.001) as significant predictors of severity.

| Symptoms b | All Patients (N = 295) | Patients with Mild COVID-19 (N = 199) | Patients with Moderate COVID-19 (N = 80) | Patients with Severe/Critical COVID-19 (N = 16) | P-Value (Multivariant Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cough | 142 (48%) | 78 (39.19) | 54 (67.50) | 10 (62.50) | 0.017 |

| Fever | 235 (79.66) | 161 (80.90) | 59 (73.75) | 15 (93.75) | - |

| Headache | 24 (8.13) | 13 (6.53) | 8 (10) | 3 (18.75) | - |

| Sore throat | 31 (10.50) | 21 (10.55) | 9 (11.25) | 1 (6.25) | - |

| Weakness | 91 (30.84) | 55 (27.63) | 25 (31.25) | 11 (68.75) | 0.284 |

| Shortness of breath | 54 (20.84) | 14 (7.03) | 30 (3.75) | 10 (6.25) | 0.000 |

| Diarrhea | 81 (40.70) | 53 (26.63) | 21 (26.25) | 7 (43.75) | - |

| Nausea/vomiting | 119 (40.33) | 84 (42.21) | 25 (31.25) | 10 (62.50) | 0.746 |

| Abdominal pain | 43 (14.57) | 24 (12.06) | 12 (15.00) | 7 (43.75) | 0.146 |

| Rhinorrhea | 69 (23.38) | 43 (21.60) | 21 (26.25) | 5 (31.25) | - |

| Anosmia/dysgeusia | 30 (10.16) | 22 (11.05) | 6 (7.50) | 2 (12.50) | - |

| Dehydration | 13 (4.40) | 1 (0.50) | 6 (7.50) | 6 (54.54) | 0.002 |

| Seizure | 28 (9.49) | 22 (11.05) | 4 (5.00) | 2 (12.50) | - |

| Anorexia | 80 (27.11) | 44 (22.11) | 25 (31.25) | 11 (68.75) | 0.219 |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Expressed as percentage.

4.3. Short-term Manifestations (≤ 2 Weeks)

General (34.23%), pulmonary (32.54%), and hematological (26.77%) manifestations predominated. Pulmonary issues included dyspnea (18.33%), abnormal chest imaging (16.94%), and hypoxemia (13.22%). Hematological manifestations featured leukopenia (12.54%) and anemia (10.84%). General manifestations involved fatigue (26.77%) and sleep disturbances (14.91%). Severe/critical cases exhibited rare manifestations (e.g., myocarditis, pulmonary embolism). Univariable analysis associated pulmonary, hematological, cardiovascular, renal, and general manifestations with severity (P < 0.001), but multivariable analysis confirmed only pulmonary (P < 0.001) and general (P = 0.02) manifestations (Table 3).

| Short-term Manifestations (Primary Endpoints) b | All Patients (N = 295) | Patients with Mild COVID-19 (N = 199) | Patients with Moderate COVID-19 (N = 80) | Patients with Severe/Critical COVID-19 (N = 16) | P-Value (Univariant Analysis) | P-Value (Multivariant Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | 96 (32.54) | 29 (14.57) | 53 (60.22) | 14 (87.50) | < 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Cough | 34 (11.50) | 7 (3.51) | 18 (22.50) | 9 (56.25) | ||

| Abnormal X-ray | 50 (16.94) | 11 (5.52) | 27 (33.75) | 12 (75.00) | ||

| Abnormal CT-scan | 27 (9.15) | 0 | 13 (16.25) | 14 (87.5) | ||

| Dyspnea | 52 (18.33) | 16 (8.04) | 22 (27.50) | 14 (87.50) | ||

| Tachypnea | 25 (8.47) | 1 (0.50) | 15 (18.75) | 9 (56.25) | ||

| Decreased SPO2 | 39 (13.22) | 2 (1.00) | 23 (28.75) | 14 (87.50) | ||

| Respiratory acidosis | 4 (1.35) | - | - | 4 (25.00) | ||

| Oxygen therapy | 19 (6.44) | 3 (1.50) | 4 (5.00) | 12 (75.00) | ||

| Intubation | 4 (1.35) | - | - | 4 (25.00) | ||

| Bacterial pneumonia | 26 (8.81) | 5 (2.51) | 12 (15.00) | 9 (56.25) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 57 (19.32) | 34 (17.08) | 17 (21.25) | 6 (37.5) | 0.139 | - |

| Diarrhea | 19 (6.44) | 13 (6.53) | 6 (7.50) | - | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | 18 (6.10) | 16 (8.04) | 2 (2.50) | - | ||

| Elevated AST/ALT | 32 (10.84) | 18 (9.04) | 8 (10.00) | 6 (37.50) | ||

| Anorexia | 15 (5.08) | 6 (3.01) | 3 (3.75) | 6 (37.50) | ||

| Weight loss | 5 (1.69) | - | 3 (3.75) | 2 (12.50) | ||

| Hepatitis | 2 (0.67) | - | - | 2 (12.50) | ||

| Mucocutaneous | 24 (8.13) | 14 (7.03) | 6 (7.50) | 4 (25.00) | 0.067 | - |

| Rash | 17 (5.76) | 13 (6.53) | 2 (2.50) | 2 (12.50) | ||

| Urticaria | 2 (0.67) | - | - | 2 (12.50) | ||

| Exfoliation | 1 (0.33) | - | 1 (1.25) | - | ||

| Mucosal edema | 2 (0.67) | - | 2 (2.50) | - | ||

| Hematologic | 79 (26.77) | 32 (16.08) | 33 (41.25) | 14 (87.50) | < 0.001 | 0.074 |

| Anemia | 32 (10.84) | 9 (4.52) | 11 (13.75) | 12 (75.00) | ||

| Leukopenia | 37 (12.54) | 13 (6.53) | 12 (15.00) | 12 (75.00) | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 13 (4.40) | 5 (2.51) | 5 (6.25) | 3 (18.75) | ||

| Thrombocytosis | 18 (6.10) | 3 (1.50) | 9 (11.25) | 6 (37.50) | ||

| Leukocytosis | 24 (8.13) | 15 (7.53) | 9 (11.25) | - | ||

| Neuromuscular | 5 (1.69) | 2 (1.00) | 2 (2.50) | 1 (6.50) | 0.116 | - |

| GuillainBarre syndrome | 1 (0.33) | - | 1 (1.25) | - | ||

| Muscle weakness and pain | 4 (1.35) | 2 (1.00) | 1 (1.25) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Eye | 5 (1.69) | 2 (1.00) | 3 (3.75) | - | 0.264 | - |

| Non-purulent conjunctivitis | 2 (0.67) | 1 (0.50) | 1 (1.25) | - | ||

| Purulent conjunctivitis | 1 (0.33) | - | 1 (1.25) | - | ||

| Lacrimation | 2 (0.67) | 1 (0.50) | 1 (1.25) | - | ||

| Cardiovascular | 31 (10.50) | 11 (5.52) | 13 (16.25) | 7 (43.75) | < 0.001 | 0.815 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 (0.67) | - | - | 2 (12.50) | ||

| Palpitation | 15 (5.08) | 6 (3.01) | 6 (7.50) | 3 (18.75) | ||

| chest discomfort | 11 (3.72) | 4 (2.01) | 3 (3.75) | 4 (25.00) | ||

| Cardiac valve disorder | 5 (1.69) | 1 (0.50) | 3 (3.75) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Pericardial effusion | 8 (2.71) | 2 (1.00) | 4 (5.00) | 2 (12.50) | ||

| Myocarditis | 2 (0.67) | - | 1 (1.25) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Renal | 12 (4.06) | 3 (1.50) | 4 (5.00) | 5 (31.25) | < 0.001 | 0.148 |

| Oliguria | 8 (2.71) | 2 (1.00) | 4 (5.00) | 2 (12.50) | ||

| Creatinine raises | 1 (0.33) | - | - | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Elevated BUN | 5 (1.69) | - | 2 (2.50) | 3 (18.75) | ||

| Pyuria | 2 (0.67) | 1 (0.50) | 1 (1.25) | - | ||

| Proteinuria | 3 (1.01) | - | 1 (1.25) | 2 (12.50) | ||

| General | 101 (34.23) | 56 (28.14) | 35 (43.75) | 10 (62.50) | 0.003 | 0.02 |

| Fatigue | 79 (26.77) | 42 (21.10) | 28 (35.00) | 9 (56.25) | ||

| Sleep disorder | 44 (14.91) | 24 (12.06) | 15 (18.75) | 5 (31.25) |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Expressed as percentage.

4.4. Long-term Manifestations (12 Weeks)

General (20.01%), pulmonary (16.06%), and hematological (7.79%) manifestations persisted. Fatigue (16.94%) and cough (9.83%) were most common. No cardiovascular, renal, or ocular sequelae were reported. Univariable analysis linked pulmonary, hematological, and general manifestations to severity (P < 0.001), but only pulmonary manifestations remained significant in multivariable models (P = 0.02, Table 4).

| Long-term Manifestations (Primary Endpoints) b | All Patients (N = 295) | Patients with Mild COVID-19 (N = 199) | Patients with Moderate COVID-19 (N = 80) | Patients with Severe/Critical COVID-19 (N = 16) | P-Value (Univariant Analysis) | P-Value (Multivariant Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary | 43 (16.60) | 10 (5.02) | 23 (28.75) | 10 (62.50) | < 0.001 | 0.029 |

| Symptom | ||||||

| Cough | 29 (9.83) | 5 (2.51) | 15 (18.75) | 9 (56.25) | ||

| Dyspnea | 25 (8.47) | 7 (3.51) | 12 (15.00) | 6 (37.50) | ||

| Paraclinic | ||||||

| Abnormal X-ray | 12 (4.06) | 3 (1.50) | 2 (2.50) | 7 (43.75) | ||

| Decreased SPO2 | 4 (1.35) | - | - | 4 (25.00) | ||

| Bacterial pneumonia | 6 (2.03) | 3 (1.01) | 2 (2.50) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Gastrointestinal | 16 (5.42) | 8 (4.02) | 7 (8.75) | 1 (6.25) | 0.201 | - |

| Paraclinic | ||||||

| Elevated AST/ALT | 6 (2.03) | 3 (1.05) | 2 (2.50) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Symptom | ||||||

| Diarrhea | 1 (0.33) | 1 (0.50) | - | - | ||

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 (0.33) | 1 (0.50) | - | - | ||

| Weight loss | 5 (1.69) | - | 4 (5.00) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Anorexia | 7 (2.37) | 3 (1.05) | 3 (3.75) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Mucocutaneous | 9 (3.05) | 6 (3.01) | 2 (2.50) | 1 (6.25) | 0.571 | - |

| Symptom | ||||||

| Rash | 6 (2.03) | 4 (2.01) | 1 (1.25) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Urticaria | 3 (1.01) | 3 (1.50) | - | - | ||

| Exfoliation | 1 (0.33) | - | 1 (1.25) | - | ||

| Hematologic | 23 (7.79) | 5 (2.51) | 10 (12.50) | 8 (50.00) | < 0.001 | 0.053 |

| Paraclinic | ||||||

| Anemia | 18 (6.10) | 5 (2.51) | 5 (6.25) | 8 (50.00) | ||

| Leukopenia | 10 (3.38) | 2 (1.00) | 7 (8.75) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (0.67) | - | 1 (1.25) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Thrombocytosis | 1 (0.33) | - | 1 (1.25) | - | ||

| Leukocytosis | 2 (0.67) | - | 1 (1.25) | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Neuromuscular | 2 (0.67) | 1 (0.50) | - | 1 (6.25) | 0.177 | - |

| GuillainBarre syndrome | 2 (0.67) | 1 (0.50) | - | 1 (6.25) | ||

| Eye | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cardiovascular | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Renal | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| General | 62 (20.01) | 34 (17.08) | 21 (26.25) | 7 (43.75) | 0.019 | 0.668 |

| Symptom | ||||||

| Fatigue | 50 (16.94) | 26 (13.06) | 17 (21.25) | 7 (43.75) | ||

| Sleep disorder | 17 (5.76) | 8 (4.02) | 8 (10.00) | 2 (12.50) |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Expressed as percentage.

4.5. Secondary Outcomes

The ICU admission (2.71%, n = 8), readmission (2.37%, n = 7), and mortality (1.01%, n = 3) occurred exclusively in moderate/severe cases. The DKA (2.71%) and MIS-C (1.01%) were rare. Most hospitalizations (91.52%) lasted < 1 week. Disease severity correlated with DKA, MIS-C, ICU stay, readmission, and mortality in univariable analysis (P < 0.05), but not in multivariable models (P > 0.05), likely due to limited event rates (Table 5).

| Secondary Endpoints b | All Patients (N = 295) | Patients with Mild COVID-19 (N = 199) | Patients with Moderate COVID-19 (N = 80) | Patients with Severe/ Critical COVID-19 (N = 16) | P-Value (Univariant Analysis) | P-Value (Multivariant Analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Possible related disorders | ||||||

| DKA | 8 (2.71) | - | 3 (3.75) | 5 (31.25) | < 0.001 | 0.998 |

| MISC | 3 (1.01) | - | 2 (2.50) | 1 (6.25) | 0.020 | 0.999 |

| COVID-19 outcomes | ||||||

| ICU hospitalization | 8 (2.71) | - | 5 (6.25) | 3 (18.75) | < 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Hospitalization < 1 wk | 270 (91.52) | 197 (99.00) | 65 (81.25) | 8 (50.00) | < 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Hospitalization 1 - 2 wk | 18 (6.10) | 2 (1.00) | 11 (13.75) | 5 (31.25) | < 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Hospitalization > 2 wk | 7 (2.37) | - | 4 (5.00) | 3 (18.75) | < 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Readmission within 3 mo post-COVI | 7 (2.37) | 2 (1.00) | 3 (3.75) | 2 (12.5) | 0.016 | 0.716 |

| Death | 3 (1.01) | - | 2 (2.50) | 1 (6.25) | 0.023 | 0.999 |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; DAK, diabetic ketoacidosis; ICU, intensive care unit.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Expressed as percentage.

5. Discussion

This study highlights the clinical trajectory and manifestations of COVID-19 in 295 hospitalized Iranian children, emphasizing disease severity as a predictor of outcomes. Consistent with global data, most pediatric cases (67.5%) were mild, while we reported 3 cases of death. Age, sex, and weight showed no association with severity, aligning with another study findings (29). However, infants < 1 year often face higher hospitalization risks (13, 15, 30), contrasting our cohort’s mean age of approximately 3 years. While obesity is linked to severe COVID-19 in other studies (31), no such association emerged here, similar to our previous study in another tertiary children’s hospital in Tehran (15), possibly due to low obesity prevalence.

Comorbidities, particularly pulmonary, neurological, and metabolic disorders, were prevalent but showed inconsistent ties to severity. Univariable analysis linked diabetes, pulmonary disease, and immune disorders to worse outcomes, but multivariable adjustments nullified these associations, suggesting confounding factors. This contrasts with our previous data, where comorbidities correlated with ICU admission and mortality (13, 15), and aligns with studies reporting no significant comorbidity-severity links (32). Asthma, a known risk factor, was underreported here, possibly reflecting regional diagnostic disparities (33).

Seth et al. discusses various COVID-19 manifestations in the pediatric population, highlighting long COVID symptoms like insomnia, respiratory problems, fatigue, and muscle/joint pain. It also reviews neuroimaging findings and respiratory manifestations seen in hospitalized children with COVID-19, including interstitial pneumonia and severe acute respiratory illness. Long COVID symptoms reported in children included fatigue, sleep disturbances, muscle/joint pain, and respiratory problems lasting weeks to months post-infection (16).

Fever (79.66%), cough (48.13%), and gastrointestinal symptoms (40.70%) dominated presentations, mirroring global trends (34). Severe disease correlated with dyspnea, dehydration, and cough, underscoring respiratory compromise as a severity marker (35). Short-term manifestations (≤ 2 weeks) included fatigue (26.77%), pulmonary (32.54%), and hematological (26.77%) issues, with pulmonary and general manifestations retaining severity associations in adjusted models. Long-term (12 weeks), fatigue (16.94%) and pulmonary sequelae (16.06%) persisted, aligning with studies reporting fatigue in up to 87% of pediatric cases (26, 36). Pulmonary manifestations remained severity-dependent, consistent with Trapani et al.’s findings (36).

Neurological and psychiatric symptoms such as headache, dizziness, and mood disorders were also noted in several studies as acute or chronic manifestations of COVID-19 infection in children (16). A large multicenter study published in 2022 analyzed neurologic manifestations in children hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United States. It found neurologic manifestations such as febrile seizures and encephalopathy were common, occurring in about 7% of hospitalized children, and associated with worse outcomes including ICU admission and higher hospital costs (37, 38). Previous studies also emphasized the importance of immunization, especially in high-risk children with neurologic comorbidities (37).

Secondary outcomes like ICU admission (2.71%), readmission (2.37%), and mortality (1.01%) occurred exclusively in moderate/severe cases, comparable to global rates (15, 31, 39). While univariable analysis linked severity to DKA, MIS-C, and mortality, multivariable models showed no significance, likely due to low event rates. This parallels Osmanov et al.’s observation of symptom persistence in 24.3% of hospitalized children (40), emphasizing the role of acute-phase severity in post-COVID risks (41).

Studies have mentioned persistent long-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on hospitalized children, lasting months after discharge, including weight loss, chronic cough, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and mood disorders, illustrating chronic manifestations in pediatric patients (33, 36, 42). Other studies noted that while COVID-19 is generally less severe in children, chronic manifestations can develop, especially in those with comorbidities. They identified prematurity, early infancy, comorbidities, and coinfections as main risk factors for developing manifestations during hospitalization and after it (13, 15, 43).

5.1. Conclusions

This study identified that initial disease severity is a significant predictor for both short- and long-term pulmonary manifestations in hospitalized children with COVID-19. While fatigue was a predominant reported issue, the strongest objective association was between more severe initial illness and persistent respiratory sequelae. Therefore, implementing a prioritized follow-up strategy, particularly for children recovering from moderate-to-severe COVID-19, is crucial to mitigate long-term pulmonary morbidity. These findings highlight the necessity of targeted pediatric post-COVID care pathways to effectively address the most consequential post-acute sequelae.

5.2. Limitations

Limitations include the retrospective design, which risks underreporting comorbidities and symptoms, and a modest sample size limiting statistical power. Data collection biases (e.g., reliance on registries, parental recall) may affect accuracy. The subjective nature of symptoms such as fatigue and sleep disturbances, in the absence of validated objective measures, constrains the clinical applicability and interpretation of our results. Despite this, our findings align with global trends, reinforcing the need for vigilance in children with moderate/severe COVID-19, particularly for pulmonary and systemic sequelae.

5.3. Implications

Fatigue and respiratory manifestations dominate post-COVID morbidity, necessitating structured follow-up for high-risk children. While severe outcomes are rare, pre-existing conditions and acute-phase severity warrant targeted monitoring. Future studies should prioritize prospective designs and larger cohorts to clarify risk factors and refine pediatric management protocols.