1. Background

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is recognized as one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders of childhood and adolescence, characterized by persistent patterns of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity that are inconsistent with developmental level (1, 2). This disorder extends far beyond academic underachievement, profoundly affecting multiple domains of functioning, particularly socio-emotional adjustment, emotional regulation, and impulse control (3, 4). In Iran, studies have reported prevalence rates of ADHD ranging from 6% to 10% among elementary school children, with a recent investigation in Khuzestan province documenting a rate of 8.5% (5, 6). These figures highlight the urgent need for effective, evidence-based, non-pharmacological interventions.

Adjustment is conceptualized as a dynamic process through which individuals achieve a harmonious balance with their environment, effectively manage emotions, establish constructive interpersonal relationships, and successfully meet life’s demands (7). In children with ADHD, adjustment difficulties manifest as challenges in adhering to social norms, sustaining positive peer and adult relationships, and coping with frustration without resorting to maladaptive behaviors (8). These children frequently exhibit deficits in emotion identification and regulation, leading to intense emotional reactivity, peer rejection, lowered self-esteem, and a perpetuating cycle of social failure (9). The Emotional Adjustment Measure (EAM) employed in the present study specifically evaluates two core dimensions: (A) dysregulation of emotional and physiological arousal and (B) hopelessness and wishful thinking (10).

In recent years, non-pharmacological interventions grounded in cognitive-behavioral principles have gained substantial empirical support for ADHD (11). Cognitive-behavioral play therapy (CBPT) utilizes play — the natural communicative medium of children — as a vehicle for teaching essential self-regulation skills, problem-solving strategies, cognitive restructuring, and emotional awareness within a developmentally appropriate and engaging framework (12, 13). Through symbolic play, children externalize internal conflicts, experiment with alternative responses, and acquire adaptive coping mechanisms in a non-threatening context (14). Meta-analytic evidence and controlled trials have consistently demonstrated the efficacy of CBPT in reducing ADHD symptomatology and improving impulse control, emotional regulation, and socio-emotional competence (15, 16).

Rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), developed by Albert Ellis (17), operates through a distinct mechanism by targeting irrational beliefs that underlie emotional disturbance and dysfunctional behavior (18). Utilizing the ABC model — where activating events (A) interact with beliefs (B) to produce emotional and behavioral consequences (C) — REBT helps children replace rigid, absolutistic thinking (e.g., “I must always be perfect” or “It’s awful when things don’t go my way”) with more rational, flexible, and adaptive beliefs (19). Empirical studies have confirmed REBT’s effectiveness in enhancing frustration tolerance, emotion regulation, impulse control, and social problem-solving skills in children and adolescents with ADHD or related externalizing disorders (20, 21). By modifying core cognitive structures, REBT produces relatively stable and generalized improvements in emotional and behavioral adjustment (20).

Despite robust evidence supporting the individual efficacy of CBPT (14) and REBT (19), direct head-to-head comparisons of these two interventions — particularly regarding their impact on psychosocial adjustment in students with ADHD — are notably scarce. Moreover, cultural variations in emotional expression, family dynamics, and socialization practices in Iran underscore the importance of evaluating and comparing these approaches within local populations. Such comparative research is essential for informing evidence-based clinical decision-making and facilitating tailored or integrated intervention protocols according to the predominant difficulties presented by each child (cognitive-belief vs. behavioral-social).

2. Objectives

The present study primarily aimed to compare the effectiveness of CBPT and REBT on psychosocial adjustment in elementary students diagnosed with ADHD. The study specifically tested whether there was a statistically significant difference between the two active interventions or between each intervention and a no-treatment control condition.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Participants

This study employed a quasi-experimental design utilizing a pre-test, post-test, and follow-up structure with a randomized control group to compare the effectiveness of the two therapeutic interventions. The statistical analyses were conducted with a significance level set at α = 0.05. The statistical population comprised all male elementary school students diagnosed with ADHD in Behbahan county, Iran, during the 2023 - 2024 academic year. Sample size was determined a priori using G*Power software for repeated measures ANOVA (within-between interaction), assuming a medium effect size (f = 0.25), power of 0.80, α = 0.05, three groups, three measurements, and a correlation among repeated measures of 0.5, yielding a recommended total sample size of approximately 45 participants (n = 15 per group). A sample of 45 eligible students was selected using convenience sampling and subsequently randomly assigned to one of three groups (n = 15 in each) of CBPT, REBT, and a waiting-list control group. Inclusion criteria required students to be officially diagnosed with ADHD and enrolled in elementary school. Exclusion criteria included having another comorbid mental disorder, receiving concurrent psychological/pharmacological treatment, failure to complete at least 80% of the therapy sessions, or incomplete questionnaire responses at any assessment point. The study was conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines approved by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University, Karaj Branch. All parents provided informed consent prior to participation, and the principles of voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw were strictly observed. As an ethical consideration, the waiting-list control group was offered the opportunity to receive one of the active interventions (at the parents’ choice) upon completion of the study.

3.2. Procedure

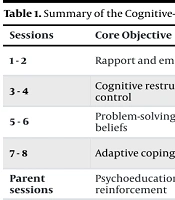

After obtaining written informed consent from the parents, the EAM was administered to all three groups as a pre-test. The experimental groups (CBPT and REBT) subsequently received their respective structured protocols, which consisted of eight weekly therapy sessions lasting 60 minutes each for the children, supplemented by two additional training sessions delivered to the parents. The interventions were conducted over eight consecutive weeks. To enhance reproducibility and ensure treatment fidelity, both interventions were delivered by the same trained therapist with expertise in cognitive-behavioral approaches. Sessions followed manualized protocols (Tables 1 and 2), with adherence monitored through weekly supervision and review of session notes. Key distinctions between the interventions included the primary modality of skill delivery: The CBPT emphasized symbolic play, puppets, and role-playing activities as the vehicle for emotional identification, cognitive restructuring, and behavioral rehearsal in a developmentally engaging format; whereas REBT relied on direct verbal instruction, didactic teaching of the ABC model, logical disputation of irrational beliefs, and structured homework assignments to promote rational thinking and frustration tolerance. A summary of the intervention sessions is presented in Tables 1. and 2. Immediately following the intervention period, the EAM was administered again to all groups (post-test). The control group received no active intervention during this period but was offered treatment upon conclusion of the study. Data collection, including the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases, was conducted by trained research assistants.

| Sessions | Core Objective | Key Activities and Skills Focused |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - 2 | Rapport and emotional awareness | Establishing trust, therapy rules, using toys/puppets to label, identify, and express feelings (emotional/physiological arousal) |

| 3 - 4 | Cognitive restructuring and self-control | Introducing the thought-feeling link, teaching self-instruction, and practicing "Stop and Think" techniques for impulse management |

| 5 - 6 | Problem-solving and challenging beliefs | Role-playing social conflicts, generating alternative solutions, and using play to challenge negative/hopeless thoughts and wishful thinking |

| 7 - 8 | Adaptive coping and generalization | Rehearsing effective social and coping skills (e.g., assertiveness), review of learned skills, and creating a plan for using skills at home/school |

| Parent sessions | Psychoeducation and reinforcement | Training parents in behavior management and techniques to support the child’s skill practice at home |

| Sessions | Core Objective | Key Activities and Skills Focused |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - 2 | ABC model introduction | Defining the difference between healthy and unhealthy emotions, introducing the (A) activating event; (B) belief; and (C) consequence model |

| 3 - 4 | Identifying and disputing irrational beliefs | Focus on rigid "musts" and "shoulds", learning to identify demandingness, and using logical/empirical (D) disputing questions |

| 5 - 6 | Developing rational beliefs and assertiveness | Replacing irrational beliefs with (E) flexible, rational alternatives; teaching coping and assertiveness techniques for social interactions |

| 7 - 8 | Frustration tolerance and consolidation | Challenging "awfulizing" and catastrophizing (reducing LFT); reducing self-downing and the subscale of hopelessness |

| Parent sessions | Modeling and homework | Educating parents on REBT principles and coaching them on how to model rational thinking and reinforce therapeutic homework |

Abbreviation: LFT, low frustration tolerance.

3.3. Measure

3.3.1. Emotional Adjustment Measure

Psychosocial adjustment was assessed using the EAM developed by Rubio et al. (10). The EAM is a 28-item self-report questionnaire designed to evaluate emotional stability and adaptive functioning in the face of affective challenges among children and adolescents. Responses are provided on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree). The instrument comprises two principal subscales of 14 items each: Lack of regulation of emotional and physiological arousal, hopelessness and wishful thinking. In the original Spanish validation study, Rubio et al. (10) reported satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.87 for the total scale and ranging from 0.82 to 0.85 for the subscales. In an Iranian adaptation and validation study, Sanaeipour et al. (22) confirmed the factorial structure and demonstrated excellent reliability in a sample of Iranian students, with Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.91 for the total score, 0.89 for lack of regulation of emotional and physiological arousal, and 0.84 for hopelessness and wishful thinking.

3.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 23). Repeated measures ANOVA was the primary technique, assessing group differences across pre-test, post-test, and follow-up phases. Assumptions were checked, and Bonferroni post-hoc tests were applied for precise pairwise comparisons.

4. Results

The final sample consisted of 45 male elementary students aged 8 - 12 years diagnosed with ADHD. The mean ages (±SD) were 10.06 ± 1.44 years in the CBPT group, 10.13 ± 1.50 years in the REBT group, and 9.93 ± 1.58 years in the control group. One-way ANOVA revealed no significant between-group differences in age (F = 0.11, P = 0.903), confirming successful randomization.

Descriptive data (Table 3) revealed comparable baseline scores across groups on all EAM variables. At post-test and follow-up, both intervention groups demonstrated marked increases in mean scores on lack of regulation of emotional and physiological arousal, hopelessness and wishful thinking, and overall adjustment, whereas the control group exhibited minimal change, indicating sustained therapeutic gains in the active treatment conditions.

| Variables and Stages | CBPT Group | REBT Group | Control Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of regulation of emotional and physiological arousal | |||

| Pre-test | 37.40 ± 7.59 | 35.53 ± 6.24 | 37.71 ± 8.43 |

| Post-test | 51.47 ± 8.04 | 48.46 ± 9.07 | 39.00 ± 6.83 |

| Follow-up | 54.53 ± 6.95 | 50.47 ± 6.64 | 39.27 ± 7.17 |

| Hopelessness and wishful thinking | |||

| Pre-test | 41.33 ± 7.07 | 39.00 ± 6.59 | 43.07 ± 7.96 |

| Post-test | 59.20 ± 6.58 | 56.73 ± 8.09 | 45.40 ± 8.11 |

| Follow-up | 58.86 ± 7.13 | 55.67 ± 6.97 | 44.53 ± 7.74 |

| Overall adjustment | |||

| Pre-test | 78.73 ± 13.56 | 74.53 ± 11.09 | 80.78 ± 14.33 |

| Post-test | 110.67 ± 11.74 | 105.20 ± 12.52 | 84.40 ± 11.45 |

| Follow-up | 113.40 ± 11.51 | 106.20 ± 10.78 | 83.80 ± 13.18 |

Abbreviations: CBPT, cognitive-behavioral play therapy; REBT, rational emotive behavior therapy.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Prior to the main analyses, normality of the EAM scores was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test across all groups and assessment points. All P-values exceeded 0.05, indicating no significant deviation from normality. Levene’s test confirmed homogeneity of variances (P > 0.05), and Mauchly’s test of sphericity was non-significant for all dependent variables; thus, no correction was required.

Mixed-design ANOVA yielded significant main effects of group and time, as well as significant group×time interactions for all dependent variables (P < 0.001). Large effect sizes were observed for time (partial η2 = 0.55 - 0.67) and group (partial η2 = 0.39 - 0.49), while interaction effects were moderate to large (partial η2 = 0.22 - 0.36), confirming that improvements over time differed substantially across groups (Table 4).

| Variables and Sources | MSE | MS | F | P-Value | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of regulation of emotional and physiological arousal | |||||

| Time | 2822.40 | 2338.20 | 50.69 | 0.001 | 0.55 |

| Group | 1952.64 | 2553.11 | 16.06 | 0.001 | 0.43 |

| Group×time | 1234.96 | 4521.02 | 5.74 | 0.001 | 0.22 |

| Hopelessness and wishful thinking | |||||

| Group | 1836.86 | 2857.78 | 13.48 | 0.001 | 0.39 |

| Time | 3192.18 | 1784.20 | 75.14 | 0.001 | 0.64 |

| Group×time | 1618.43 | 4005.82 | 8.48 | 0.001 | 0.29 |

| Overall adjustment | |||||

| Group | 7571.66 | 7850.44 | 20.5 | 0.001 | 0.49 |

| Time | 12017.78 | 5890.29 | 85.69 | 0.001 | 0.67 |

| Group×time | 5645.36 | 11210.33 | 10.58 | 0.001 | 0.36 |

Bonferroni-adjusted within-group comparisons showed that both intervention conditions produced highly significant improvements from pre-test to post-test and from pre-test to three-month follow-up on all EAM variables (P < 0.001). No significant differences emerged between post-test and follow-up (P > 0.78), demonstrating maintenance of treatment gains over the follow-up period (Table 5).

| Variables and Comparisons | Mean Difference | SE | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of regulation of emotional and physiological arousal | |||

| Pre-test/post-test | -9.42 | 1.51 | 0.001 |

| Pre-test/follow-up | -11.20 | 1.57 | 0.001 |

| Post-test/follow-up | -1.78 | 1.56 | 0.782 |

| Hopelessness and wishful thinking | |||

| Pre-test/post-test | -12.64 | 1.52 | 0.001 |

| Pre-test/follow-up | -11.91 | 1.37 | 0.001 |

| Post-test/follow-up | 0.73 | 1.47 | 0.999 |

| Overall adjustment | |||

| Pre-test/post-test | -22.07 | 2.49 | 0.001 |

| Pre-test/follow-up | -23.11 | 2.51 | 0.001 |

| Post-test/follow-up | -1.04 | 2.32 | 0.999 |

Between-group post-hoc tests at post-test indicated that both the CBPT and REBT groups significantly outperformed the control group on all outcome measures (P < 0.001), with mean differences ranging from 6.16 to 17.93 points. No statistically significant differences were found between the CBPT and REBT groups on any variable (P = 0.173 - 0.408), indicating comparable efficacy of the two active interventions (Table 6).

| Variables and Comparisons | Mean Difference | SE | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of regulation of emotional and physiological arousal | |||

| CBPT group/REBT group | 2.98 | 1.64 | 0.232 |

| CBPT group/control group | 9.13 | 1.64 | 0.001 |

| REBT group/control group | 6.16 | 1.64 | 0.001 |

| Hopelessness and wishful thinking | |||

| CBPT group/REBT group | 2.64 | 1.74 | 0.408 |

| CBPT group/control group | 8.80 | 1.74 | 0.001 |

| REBT group/control group | 6.16 | 1.74 | 0.001 |

| Overall adjustment | |||

| CBPT group/REBT group | 5.56 | 2.39 | 0.173 |

| CBPT group/control group | 17.93 | 2.39 | 0.001 |

| REBT group/control group | 12.31 | 2.39 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CBPT, cognitive-behavioral play therapy; REBT, rational emotive behavior therapy.

5. Discussion

This study investigated and compared the efficacy of CBPT and REBT in enhancing the adjustment levels of elementary school students diagnosed with ADHD. The principal findings demonstrated that both CBPT and REBT protocols were significantly effective in improving overall adjustment scores, as well as the subscales of lack of regulation of emotional/physiological arousal and hopelessness and wishful thinking, compared to the control group. Crucially, the analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in the magnitude of effect between the two active interventions, and the improvements were maintained at the three-month follow-up.

The finding supporting the effectiveness of CBPT on student adjustment aligns with a growing body of literature highlighting the utility of behavioral and cognitive interventions for ADHD symptoms (16). This efficacy can be attributed to the unique mechanism of CBPT: Utilizing play, the child’s natural means of communication, to teach complex skills. For children with ADHD, who often struggle with generalizing skills taught through verbal instruction, the structured play environment acts as a low-stakes, concrete laboratory for rehearsing essential executive functions like self-control and impulse regulation (5). The focused activities in the CBPT protocol directly addressed the lack of regulation of emotional and physiological arousal, allowing students to externalize their intense feelings through play and practice cognitive restructuring and self-instruction techniques (12). This hands-on approach directly facilitates the development of adaptive coping strategies and enhances their capacity for emotional modulation, ultimately leading to better social and emotional adjustment. Research by Sheykholeslami et al. (23) similarly confirmed that interventions focusing on improving executive functions (a core component of CBPT) led to enhanced adaptive behavior and learning in children with neurodevelopmental disorders, supporting the mechanism observed in the present study.

The positive impact of the REBT protocol on adjustment is consistent with previous research demonstrating its effectiveness in improving emotional regulation and reducing dysfunctional behaviors in child populations (24, 25). The REBT’s effectiveness was particularly notable in reducing the subscale of hopelessness and wishful thinking. This subscale reflects an inability to constructively face life’s difficulties, often exacerbated by the high levels of frustration and low frustration tolerance (LFT) characteristic of ADHD. The REBT protocol systematically challenges the rigid, absolutistic, and demanding irrational beliefs (the 'B' in the ABC model) that underpin emotional distress and maladaptive consequences ('C'). By teaching students to dispute these beliefs and replace them with flexible, rational alternatives, the intervention empowered them to tolerate frustration and failure more effectively (19). This cognitive shift resulted in diminished emotional reactivity and improved overall coping, directly translating into better adjustment.

The central finding — the absence of a statistically significant difference in effectiveness between CBPT and REBT — holds significant clinical relevance. This comparable efficacy suggests that, despite the differences in delivery modalities (play vs. verbal-rational dialogue), both interventions achieve similar outcomes because they share a fundamental cognitive-behavioral theoretical framework (15, 18). Both protocols are inherently structured and target the core deficits underlying poor adjustment in ADHD, namely: Improving self-talk, enhancing self-control, and modifying maladaptive behavioral responses. Whether the cognitive restructuring is delivered indirectly through symbolic play (CBPT) or directly through logical disputation (REBT), the final behavioral and emotional outcomes are equivalent. This conclusion is supported by literature comparing focused cognitive and behavioral interventions, which often find comparable outcomes when the intervention targets similar underlying mechanisms.

The equivalent effectiveness of CBPT and REBT provides practitioners with greater flexibility in selecting a treatment modality for students with ADHD. The choice of intervention can now be guided by pragmatic considerations, such as the child’s developmental level, verbal abilities, resistance to direct talk therapy, and the specific resources available in clinical or school settings. For example, CBPT may be prioritized for younger children or those with less developed verbal reasoning skills, while REBT may be more efficient for older elementary students capable of engaging in abstract, logical discussion. Ultimately, both offer robust, evidence-based, non-pharmacological avenues for promoting stable improvements in psychosocial adjustment.

The generalizability of these findings is subject to several practical limitations. The study employed convenience sampling from a single geographical area in Iran, which restricts external validity and limits the extent to which results can be generalized to broader populations, including female students or those from diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Although random assignment to groups was successful in balancing age (as confirmed by one-way ANOVA), the non-probability sampling method raises concerns about potential unmeasured selection biases and whether the sample fully represents the heterogeneity of elementary students with ADHD. Additionally, the sample size of 45 participants (n = 15 per group), while adequately powered for detecting medium-to-large main effects and interactions, may have been insufficient to reliably identify smaller, subtle differences in efficacy between the two active interventions. Future studies could address this by conducting formal non-inferiority testing or employing larger samples to more confidently establish equivalence. Further limitations include the reliance on child self-report measures without multi-informant assessments (e.g., teacher or parent reports) and the relatively short follow-up period. Future research should consider multi-informant assessments (e.g., teacher reports and objective performance tests) to validate results and should include long-term follow-up periods (e.g., six months to one year) to better gauge the maintenance of therapeutic gains.

5.1. Conclusions

In summary, this study conclusively demonstrated that both CBPT and REBT are highly effective non-pharmacological interventions for enhancing the psychosocial adjustment of elementary students with ADHD. Both approaches significantly improved emotional regulation and reduced hopelessness compared to a control condition, with effects sustained at follow-up. Crucially, while no statistically significant differences were observed between the two interventions, the absence of superiority should be interpreted cautiously given the modest sample size, which may have limited power to detect subtle differences; future research incorporating non-inferiority analyses would help confirm therapeutic equivalence. This finding of comparable efficacy suggests that clinicians possess two equally reliable and viable therapeutic options. This flexibility allows practitioners to tailor the choice of intervention based on the child’s developmental profile and specific clinical needs, thus confirming the clinical utility of cognitive-behavioral approaches in school-based mental health programs.