1. Context

Diabetes mellitus affects blood glucose metabolism and comprises two main types: Type 1, resulting from relative or absolute insulin deficiency, and type 2, arising from insulin resistance (1). In recent years, oxidative stress has garnered significant attention due to its substantial impact on human health and the onset of metabolic diseases such as diabetes (2). In 1980, the global prevalence of diabetes was approximately 4.7%. Over subsequent decades, this rate increased markedly, and according to the latest data from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), by 2045, nearly 783 million people (12.2%) will have diabetes (3). Diabetes complications are broadly categorized into microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy) and macrovascular (stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease) (4). Furthermore, conditions such as heart failure, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, and disorders of neuronal origin are common in diabetic patients (5, 6). The correlation between diabetes and the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease is so pronounced that the latter is recognized as a brain-specific metabolic disorder, increasing mortality risk and threatening quality of life (3, 7).

Studies indicate that the body may possess a "memory" of past metabolic environments, such as hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia. This "metabolic memory" can perpetuate the development of chronic inflammatory disorders and metabolic diseases, even after normalization of metabolic parameters, and may also impact future generations (8). Given the intricate relationship between oxidative stress, metabolic memory, and diabetes prevalence, targeted interventions like physical activity and dietary control are proposed as fundamental, non-pharmacological components of lifestyle management for this disease (9). Therefore, this review study will elucidate oxidation under normal conditions, the mechanisms influencing oxidative stress, and its role in metabolic memory during hyperglycemic states. Subsequently, it will examine the impact of a healthy lifestyle — specifically engaging in exercise and adhering to an appropriate diet, which has recently attracted researchers' focus.

2. Oxidative Stress in Hyperglycemia and Its Cellular-Molecular Mechanisms

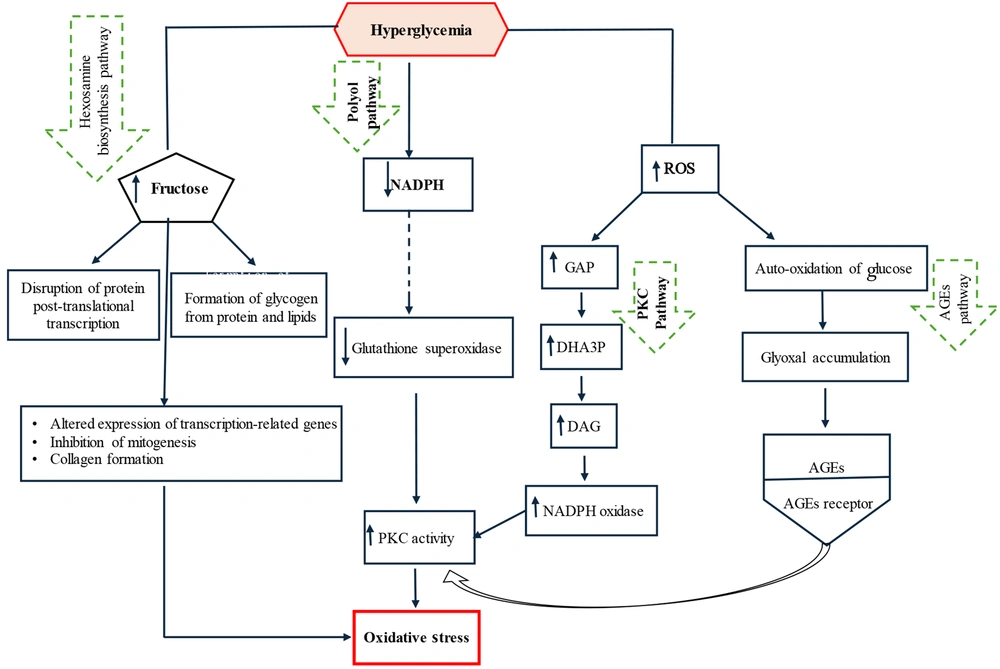

An imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the capacity of antioxidant defense mechanisms leads to disorders caused by increased oxidative stress, initiating a series of adverse effects (10, 11). Excessive ROS accumulation damages cellular components such as proteins, lipids, and DNA. By disrupting cellular and mitochondrial functions, it stimulates inflammatory responses and threatens the integrity of key cellular elements. Oxidative stress is a root cause of many chronic diseases, such as diabetes (4, 12). Oxidative stress-activated protein kinases lead to the activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) and inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase subunit beta (IKK-β). These proteins, belonging to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, phosphorylate and inhibit the insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1), thereby disrupting downstream insulin signaling pathways (2). Stimulators of oxidative stress and inflammation are more prevalent in obese individuals and, by limiting the synthesis and release of adiponectin, impair insulin's ability to facilitate glucose uptake into cells (3, 13). Under normal conditions, glucose taken up by cells is metabolized oxidatively via the pentose phosphate pathway, increasing the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and providing precursors for biosynthesis (14). Furthermore, enzymatic antioxidants including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) control ROS production — an inherent feature of mitochondrial respiration — by preventing excessive accumulation of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), superoxide ion (O₂•⁻), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•) (15). Hyperglycemia intensifies ROS production, suppresses the effectiveness of antioxidant enzymes, and increases the accumulation of glycolytic substrates including glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP), glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), and fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) (14). Hyperglycemia stimulates oxidative stress through four major signaling pathways: The polyol (sorbitol) pathway, the hexosamine pathway, protein kinase C (PKC) activation, and the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (16).

Under hyperglycemic conditions, oxidative stress resulting from overproduction of free radicals causes DNA damage and accumulation of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP) and dihydroxyacetone-3-phosphate (DHA3P) in the glycolytic pathway. In the presence of free fatty acids, GAP leads to the synthesis of diacylglycerol (DAG), thereby activating the PKC pathway (14). Heightened PKC activity stimulates ROS-generating enzymes such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH oxidase) and lipoxygenase, exacerbating cellular oxidative stress (17). Furthermore, the accumulation of GAP — a key factor in diabetes-related oxidative stress — activates the AGE and PKC pathways. Advanced glycation end products are a heterogeneous group of proteins and lipids formed under hyperglycemic and renal failure (uremic) conditions, which stimulate the synthesis of modified proteins (17, 18). Indeed, hyperglycemia, through the spontaneous oxidation and accumulation of glucose, forms glyoxal, a direct precursor of AGEs. Subsequently, the binding of AGEs to their receptors facilitates oxidative stress and directly stimulates PKC pathways (19).

The hexosamine pathway plays a role in the metabolism of fructose-6-phosphate derived from glycolysis. Hyperglycemia, by increasing the flux of fructose-6-phosphate into the hexosamine pathway, affects the activity of mediators and enzymes involved in the post-translational modification of proteins (20). This leads to increased expression of transcription factors such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), resulting in the inhibition of mitogenesis in kidney, liver, heart, and brain cells, activation of collagen matrix proliferation, and basement membrane thickening. Thus, diabetes-induced disorders in vital body tissues are exacerbated (14). The polyol pathway is a minor, low-activity route for glucose metabolism under normal conditions, but under hyperglycemia, it significantly impacts glucose metabolism. The activity of this pathway depletes NADPH, leading to a weakened antioxidant defense system and increased oxidative stress (21). Additionally, by increasing fructose accumulation, it elevates the formation of methylglyoxal as an AGE precursor and ultimately stimulates oxidative stress by activating the PKC pathway (2). Figure 1 illustrates the signaling pathways through which hyperglycemia increases oxidative stress.

The molecular mechanism of hyperglycemia's impact on oxidative stress. Glucose increases oxidative stress through four major pathways: The hexosamine pathway, the polyol pathway, protein kinase C (PKC) activation, and the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs). Key intermediates include glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP), dihydroxyacetone-3-phosphate (DHA3P), diacylglycerol (DAG), and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NADPH oxidase) (2).

Inflammation and oxidative stress have a bidirectional interaction in the pathogenesis of diabetes (22). In hyperglycemia, increased inflammation, by activating the immune system through pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, recruits ROS-producing macrophages to combat pathogens. This, in turn, perpetuates excessive ROS production, impairs cellular antioxidant defenses, and causes oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA (14, 23, 24). Excess ROS activates redox-sensitive transcription factors such as nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and pro-inflammatory adipokines, increasing the production of cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and IL-6 (14, 16). In diabetes, the expansion of visceral adipose tissue increases the secretion of these adipokines, thereby stimulating systemic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, which are key precursors to macro- and microvascular complications (16).

3. Metabolic Memory and Its Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms

Despite the rising prevalence of diabetes mellitus and advances in diagnosis and medical care, the factors driving disease progression in its early stages are not yet fully understood, leading to serious complications and increased mortality in patients (25). Poor metabolic control of hyperglycemia in the early stages of the disease has detrimental effects, including endothelial dysfunction, cardiovascular failure, and organ damage (2). Early hyperglycemia, even if transient, impairs vascular repair capacity due to epigenetic changes in various cell types, resulting in the establishment of "glycemic vascular memory" or "metabolic memory" (26). This phenomenon, driven by inflammatory and oxidative stimuli, remains highly influential in the development of cardiomyopathy even following metabolic readjustment (27). The concept of metabolic memory is a broad pathophysiological term associated with systemic metabolic dysregulation in diabetes and was first proposed in 1983 (28, 29). Driven by inflammatory triggers and oxidative stress, this phenomenon extends to all underlying cellular-molecular mechanisms and biochemical pathways involved in the development of diabetic complications (27). Subsequent studies on diabetes continued from 1994 onward, leading to the proposal of glycemic vascular memory — a clinical term and a subset of metabolic memory. This concept posits the persistence of hyperglycemic complications and associated tissue damage even after glycemic control is achieved (28). Although the two terms are often used synonymously, it is clear that metabolic memory encompasses more than tight blood glucose control alone. In fact, the concept of metabolic memory highlights the need for very early aggressive and pharmacological interventions aimed at metabolic control, which, beyond normalizing glucose levels, also reduce cellular reactive species and glycation, thereby minimizing the long-term complications of diabetes (28, 29).

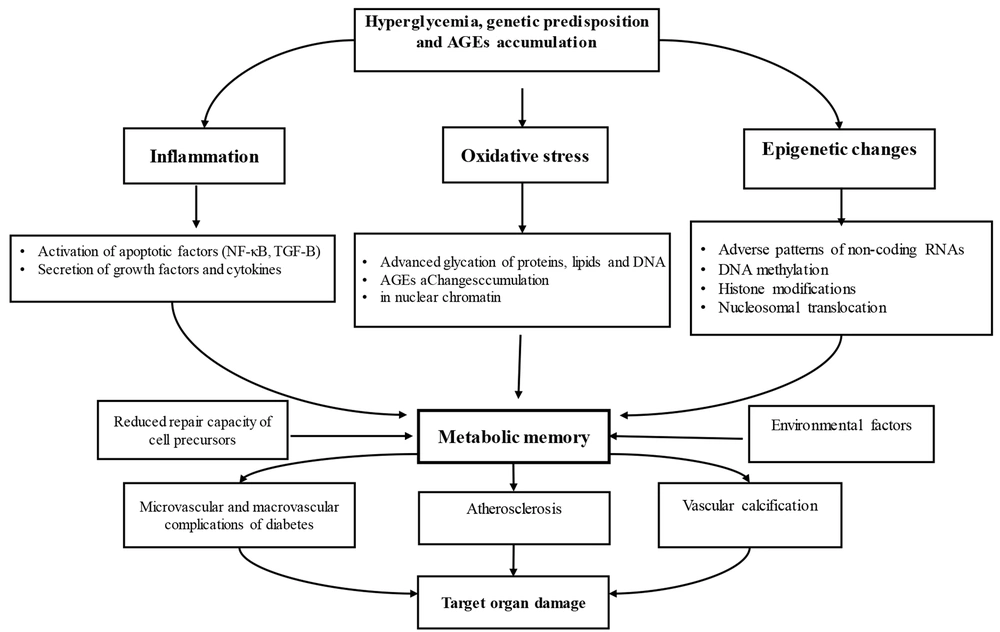

Metabolic memory is governed by a complex network of intertwined mechanisms, primarily including epigenetic regulation, advanced glycosylation end products, and oxidative stress. It refers to the persistence of the harmful effects of a past abnormal metabolic state, even after metabolic control improves (27). This phenomenon indicates the body's ability to "remember" past metabolic environments, such as hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia (22). Metabolic memory severely exacerbates microvascular complications of diabetes, such as retinopathy and nephropathy, leading to chronic inflammatory disorders and lasting negative effects on the heart, blood vessels, and tissues, even decades after the initial metabolic disturbances have been resolved (30). Indeed, metabolic memory is a key concept for understanding the long-term consequences of metabolic disorders, emphasizing the importance of early intervention and sustained optimal metabolic control to prevent chronic and late complications such as retinopathy (30, 31). Furthermore, another concept known as "metabolic legacy" exists, which refers to the sustained protective and positive effects resulting from good and early glycemic control. However, these benefits gradually diminish over time if glycemic control becomes lax (26). Although very limited studies have been conducted in this area and there are serious challenges in analyzing the concepts, studies nonetheless suggest that the impact of several key epigenetic factors in metabolic memory — including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs — appears significant. These factors exacerbate metabolic complications in diabetes by affecting angiogenesis, apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress (32). These changes allow cells to rapidly adapt to environmental shifts in a way that persists even under normoglycemic conditions and can potentially be transmitted to the next generation (8). High blood sugar increases DAG and activates PKC, leading to increased ROS production. This mechanism damages intracellular structures, including mitochondrial DNA, and perpetuates a harmful cycle even after glycemic control is achieved (2). Long-term exposure to hyperglycemia leads to a selective increase in the expression of nitric oxide synthase and subsequently nitric oxide. Consequently, superoxide radicals enhance the formation of peroxynitrite, a potent oxidant with toxic effects on the vascular network (27). As mentioned earlier, AGEs are glycated products formed through non-enzymatic reactions and accumulate over time. By interacting with their receptors, these products activate inflammatory pathways, increase NF-κB, promote ROS generation, and cause vascular damage. They play a key role in activating metabolic memory by stimulating mitochondrial injury (25, 33). Examining inflammatory processes, which manifest through an imbalance between pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-35, IL-10, and IL-4) at onset and during the first year of the disease, indicates that anti-inflammatory cytokines are effective in controlling the disease and preventing its severity over the course of the illness by modulating glycemic indices. However, initial pro-inflammatory cytokines have a lesser impact on exacerbating disease complications (22, 25).

Despite empirical evidence regarding the actual impact of blood glucose control on diabetic complications, the concept of metabolic memory remains debated. Neubauer-Geryk et al. (2024), in a study on young patients with type 1 diabetes, reported that individuals with better blood glucose control in the first year of the disease had lower levels of pro-inflammatory and higher levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines two years after disease onset compared to other patients (31). A notable point in this study is the sustained impact of glycemic and metabolic memory on the immune system, independent of the patients' current blood glucose levels, effectively highlighting the importance of early hyperglycemic control in this disease. Indeed, increased oxidative stress and AGEs following hyperglycemia, by stimulating inflammatory pathways and reducing the protective effects of anti-inflammatory cytokines, lead to epigenetic changes, exacerbate inflammation, and cause vascular damage (31, 32). Patel et al. (2008) reported that intensive blood glucose control maintained for a significant period (3 to 6 years) significantly reduces albumin excretion rates in diabetic patients but does not affect microvascular complications or the risk of myocardial infarction (33, 34). These results led to widespread disappointment among those affected by diabetes. However, Bianchi et al. (2013) reported that while achieving normal blood glucose control in patients who had already developed micro- and macrovascular complications due to prior sustained hyperglycemia could not reduce cardiomyopathy complications, early intervention and mitigation of the effects of an adverse metabolic environment can control metabolic memory and reduce complications (26). It seems that to fully understand the impact of blood glucose control on metabolic memory, clinical trials need to be designed for extended periods or should examine patients with less prior exposure to hyperglycemia (35). The effect of delayed intervention in blood glucose control on increasing oxidative stress and retinopathy in diabetic rats has also been reported (26) (Figure 2).

Molecular mechanisms of metabolic memory. Hyperglycemia, accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), and genetics stimulate metabolic memory through epigenetic changes, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Consequently, they lead to vascular damage and exacerbate micro- and macrovascular complications, resulting in damage to target organs (27).

While the precise cellular and molecular mechanisms remain challenging, evidence indicates that glycemic memory exerts sustained and deleterious molecular changes on the cardiovascular system primarily through two interconnected pathways. One pathway involves the formation and accumulation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which, by upregulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), leads to inhibition of DNA synthesis in target cells, increased vascular permeability, induction of pathological angiogenesis, and consequently, a prothrombotic state (26). The other pathway entails the accumulation of oxidative stress and ROS, which, via activation of the polyol pathway, results in the formation of peroxynitrite. This molecule promotes cellular damage and the development of microangiopathy through the oxidation and nitration of lipids and proteins (36). Indeed, the most critical feature of glycemic memory is the accumulation of AGEs and ROS, which, by inducing stable epigenetic modifications, persistently upregulate the expression of genes associated with inflammation and oxidative stress, even after blood glucose levels have normalized. This mechanism explains how a transient period of hyperglycemia can instigate long-term molecular memory in tissues (27).

4. Metabolic Memory, Muscle Memory, and Exercise

Maintaining or increasing muscle mass, in addition to facilitating movement, plays a primary role in energy homeostasis and glucose utilization, and helps prevent chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. However, sarcopenia, which intensifies with aging, accelerates the loss of muscle mass and strength, reducing the quality of life in older adults (37). Therefore, identifying therapeutic or adjunctive methods such as exercise to delay the onset of sarcopenia and preserve skeletal muscle health plays a vital role in maintaining overall body health.

Exercise, particularly resistance training, is a powerful lifestyle intervention that can protect against age- and disease-related muscle atrophy, while improving mitochondrial function, metabolic capacity, and aerobic fitness (37, 38). In recent years, the concept of "muscle memory" has emerged, describing the body's ability to perform previously learned tasks even after long periods of detraining, and examining the persistence of metabolic benefits derived from muscle function in the long term (39). Although conflicting evidence exists from human and animal models, the preservation of muscle cell nuclei during periods of training cessation may serve as a stimulus for muscle memory (38, 39).

Studies indicate that changes in the epigenome — including DNA methylation and demethylation and acyl-CoA abundance in cell nuclei — can reduce the expression of genes involved in mTOR and autophagy pathways following endurance and resistance activity in animal models. This reduction persists even during the detraining period (37). Exercise induces lasting adaptations by increasing levels of factors such as PGC-1α, leading to increased mitochondrial density and volume. Mitochondria act as essential cellular mediators in regulating muscle memory and energy metabolism (39, 40). Furthermore, exercise upregulates other indicators associated with muscle memory, such as the myogenic transcription factor MYC, which is crucial in myogenesis and energy metabolism (41). By regulating glycolytic flux and pyruvate metabolism, exercise can thereby influence cellular energy metabolism (26, 39). Weidenhamer et al. (2025), in an animal study, examined the effects of training, detraining, retraining, and a high-fat dietary challenge on cellular structures, metabolism, and muscle memory. They reported that despite reduced running volume during the retraining period, a relative increase in muscle mass was maintained, and significant improvements in mitochondrial metabolism were observed. Additionally, exercise memory from the prior training period mitigated the negative effects of a high-fat diet on metabolism (39). These findings highlight the potential of exercise as a powerful mechanism for enhancing resilience and metabolic memory. Although more research is needed, it appears that endurance retraining, despite lower volume and regardless of diet, leads to greater muscle growth compared to the initial training phase, while also promoting a metabolic shift from a glycolytic to an oxidative state (39, 42). Pilotto et al. (2025) examined 7-week periods of training, detraining, and resistance retraining, reporting that during retraining, weight control through reduced fat mass was observable in individuals with prior exercise experience, while others showed an increase in fat mass (43). Among the pathways and regulators of muscle memory following exercise, the role of PGC-1α is prominent as a mediator of mitochondrial biogenesis and epigenetic responses (38, 44). Deletion of this factor in animal models leads to epigenetic changes, increased DNA methylation, mitochondrial damage, and metabolic dysregulation. Consequently, given the central role of mitochondria in encoding muscle memory, the role of exercise as an effective mechanism in metabolic memory is strengthened (38, 43). Appropriate intensity exercise can induce the expression of antioxidant enzymes and, by downregulating oxidative stress and AGEs in obese models, exert regulatory effects on blood glucose control and reduce mortality associated with AGE accumulation in diabetic patients (18). The recommended amount of daily exercise for weight maintenance, chronic disease prevention, and general health benefits is 150 minutes per week of moderate activity, preferably a combination of aerobic and strength exercises, which can be increased up to 300 minutes per week in treatment plans for many chronic diseases (45). Overall, the downregulation of oxidative stress and AGEs in both healthy and diseased models is associated with reduced cardiovascular and renal disorders and increased lifespan (18, 19). Yoshikawa et al. (2009) reported the effect of a 12-week program of a healthy diet and a combined (aerobic and strength) exercise regimen on reducing serum AGE levels in healthy women aged 37 to 70 years (46). Furthermore, previous studies have shown that high-fat diets stimulate inflammatory and proteolytic pathways and damage oxidative metabolism. In obese individuals, reduced lipid oxidative capacity is linked to decreased metabolic flexibility in muscle and impaired insulin sensitivity — a disorder that can be significantly regulated through dietary control and exercise (39, 47). Interestingly, prior endurance training leads to a lasting metabolic memory in skeletal muscle, which stimulates oxidative metabolism, cell growth, and mitochondrial biogenesis. These effects can persist for some time even after exercise cessation (39). Studies on experimental models of metabolic memory indicate that epigenetic mechanisms, which play a role in the adverse effects of hyperglycemia and are predisposing factors for various diseases including diabetes, may also occur in response to environmental factors such as dietary changes (48). These changes have the ability to influence gene expression and phenotype without altering the DNA sequence (27). Dietary restriction without malnutrition is one of the most powerful dietary interventions for increasing lifespan and delaying age-related diseases. Through various mechanisms, it improves glucose homeostasis (increased glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity), reduces systemic inflammation, alters fatty acid metabolism, and decreases visceral fat across various organisms, from rodents to primates (31). Matyi et al. in 2018 investigated the effects of 10%, 20%, and 40% dietary restriction compared to free access in male C57BL/6 mice and reported that 4 months after the end of the research intervention, the metabolic memory effect in the 40% dietary restriction group was more pronounced than in other groups. Consequently, reductions in hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, weight control, and inflammatory responses were observed in this group. In contrast, other methods of dietary restriction had only short-term (2-month) effects on metabolic memory, showing no difference from the control group after 4 months (48). Furthermore, studies show that chronic high-fat diets reduce muscle protein synthesis and fiber cross-sectional area, leading to muscle atrophy and a shift towards glycolytic fiber types (19). In contrast, the stability of the exercise memory effect on skeletal muscle metabolism control, reported even in the presence of an obesogenic dietary challenge, is noteworthy. This highlights the potential importance of exercise in muscle and metabolic memory more than ever (39). Although the effects of exercise and dietary control on improving metabolic memory may stem from persistent epigenetic changes or metabolic programming, further and more in-depth investigations are needed (39, 49).

5. Conclusions

Glycemic memory is a pathophysiological phenomenon in which the initial accumulation of AGEs and ROS due to hyperglycemia establishes a foundation for the long-term development and progression of diabetic complications. This occurs through the induction of persistent epigenetic changes and chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, even if glycemic control is later optimized (27). Thus, a concept broader than blood glucose control, known as metabolic memory, emerges, encompassing wider epigenetic dimensions. Metabolic memory challenges conventional treatments for metabolic diseases. Consequently, despite achieving optimal glycemic control with glucose-lowering medications, organisms may continue to exhibit inflammatory responses and related complications due to metabolic memory (49). The persistence of adverse effects from metabolic memory — such as inflammatory changes, premature cellular aging, and apoptosis — varies depending on the source, extent, and duration of the stimulus. It may even trigger potentially fatal complications after maintaining near-normal glucose levels (25, 33).

Although the precise molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not fully elucidated, inflammation, oxidative stress, and epigenetic changes are key factors in metabolic memory in diabetes. The use of pharmacological and genetic approaches, alongside lifestyle modification, is proposed as a strategy to reverse the phenomenon of metabolic memory in diabetes. It appears that exercise memory in skeletal muscle is encoded through mitochondrial pathways, facilitating oxidative metabolism and fatty acid utilization during retraining (25, 43). Understanding the mechanisms related to muscle memory (1) and long-term adaptations in skeletal muscle metabolism can provide a basis for therapeutic interventions, especially in the elderly population who are seriously threatened by increasing sarcopenia and metabolic disorders (37, 39). However, future clinical trials are needed to gather more information on optimally selecting therapeutic and adjunctive methods for early intervention and achieving sustained effects to minimize the impact of metabolic memory in diabetes.