1. Background

Currently, the COVID-19 virus, which in some patients leads to severe respiratory distress syndrome and may even lead to the death of some patients, is a pandemic or widespread and is spreading in all countries (1). The lack of definitive treatment or prevention and the prediction of some epidemiologists that at least 60% of the population is infected with this disease has caused a lot of stress and anxiety in communities (2). On the other hand, the fear and anxiety caused by a possible illness are destructive and can lead to mental abnormalities and stress in people (3). If this fear and stress persist for a long time, it will be destructive and weaken the immune system and decrease the body's ability to fight diseases such as Covid-19 (4). The adolescence period is one of the most important transitions in human development; biological, psychological, and social forces affect adolescent development (5). Some adolescents enter the adolescence period with parental support and family accompaniment; however, some adolescents who do not have adequate social support in the family and the environment or have had punitive reactions in the correctional center may be affected by their interactions and future (6). Neglected and abused children are deprived of educational and psychological presence, the effective support of their parents, and the benefits of living in a family. Caring, empathic understanding and participation, transparent power structure, and problem-solving are essential family tasks. But neglected and abused children are deprived of this blessing and grow up in quasi-family centers (7). Traumatic experiences in childhood are one of the main causes of disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder. Unaccompanied children are among the most vulnerable to mental disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (8). The experience of losing parents in children is considered to be one of the main causes of post-traumatic stress disorder, and children who lose their parents are even more likely to show signs of post-traumatic stress disorder than children who have been traumatized by the occurrence of natural disasters (9, 10). One of the therapeutic interventions in educational environments was stress management training, which its success has been proven to improve people's mental health (11, 12). Stress management is a continuous process of monitoring, detecting, and preventing excessive stressful stimuli that have detrimental effects on the efficiency and effectiveness of individuals (13). One of the stress management programs is education based on the principles and methods of mindfulness-based treatment (14). Kabat Zayn et al. cited in Segal et al. defines mindfulness as paying attention to a specific, purposeful model in the present without judgment and prejudice (15). In mindfulness, a person becomes aware of his mental method at every moment, and after being aware of the two ways of the mind, one doing and the other being, he learns to move the mind from one method to another, which requires the training of the specific behavioral, cognitive, and metacognitive strategies to centralize the attention process (15). Research has shown that mindfulness-based stress reduction training is effective on anxiety and depression (16-28), perceived stress and fatigue and burnout of students (29), and emotional problems (30-33).

Therefore, given that most adolescents are in school environments, it is necessary to recognize emotional problems and ways to deal with these adversities and use them because emotional problems affect adolescent performance. Few studies, superficial and untested solutions have been suggested, which means it is necessary to use interventions based on innovative and modern tactics to address the behavioral, emotional, and cognitive characteristics of adolescents on the path to achieving their educational and training goals.

2. Objectives

The present study seeks to answer the question of whether mindfulness-based stress reduction training at the peak of the Covid-19 epidemic affects the post-traumatic stress and effects of abused and unaccompanied adolescents at the correctional center.

3. Methods

The present study was a quasi-experimental study with a pretest and posttest design with a control group. The present study's statistical population consisted of all Zahedan Correctional Center adolescents. The sampling method was the convenience method. In the first stage, 56 abused and unaccompanied adolescents were selected for screening, and in the next stage, based on the inclusion criteria, 30 adolescents were selected and randomly assigned into two groups of 15 (experimental and control groups). Mindfulness-based stress reduction training was then applied to the experimental group. Mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention (34) was conducted on the experimental group in eight two-hour sessions every other day (Table 1). At the end of the training sessions, the experimental and control groups again answered the measuring instrument as a posttest.

| Sessions | Details |

|---|---|

| First | Getting to know and establishing relationships with the group members, determining the rules governing the meetings, discussing the impact of the training, conducting the pretest |

| Second | Examining the mind and its related theories-introducing mindfulness task: Practicing eating raisins |

| Third | Reviewing the experiences of pre-assignment sessions: three-minute breathing exercises and sitting meditation |

| Fourth | Homework review: Mountain breathing practice, practice writing negative judgments about others in the last week |

| Fifth | Reviewing the experiences of pre-homework sessions: practicing physical examination, looking at candles |

| Sixth | Reviewing the experiences of the previous sessions - completing the calendar of pleasant events, the lake meditation |

| Seventh | Reviewing the experiences of previous meetings - completing the calendar of unpleasant events |

| Eighth | Reviewing the experiences of the previous sessions - reviewing the assignment - summarizing - completing the post-exam |

Design of Mindfulness Intervention Sessions Based on Stress Reduction

Criteria for entering the research: (1) abused and unsupervised youths of the correctional center; (2) not having specific physical and mental problems; (3) having consent to participate in the research.

Exclusion criteria from the research: (1) dissatisfaction with cooperation in the work process; (2) suffering from an acute physical and mental illness during the research; (3) inability to do homework outside the meeting

3.1. Data Collection Tools

3.1.1. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaire

Post-traumatic stress disorder is a self-report scale used to assess the extent of the disorder and to screen these patients from normal people and other patients as a diagnostic aid tool. This list was prepared by Withers et al. (1993, cited in Goodarzi) based on diagnostic criteria for the US National Center for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder and included 17 items, of which 5 of them are related to the signs and symptoms of re-experiencing a traumatic accident, 7 of them related to the signs and symptoms of emotional numbness and avoidance and five items related to the signs and symptoms of severe arousal. The scoring method is obtained as a Likert (1 = not at all, two = very little, 3 = medium, 4- high, 5 = very high) and is in the range of 17 - 85. Withers et al. (1993, cited in Goodarzi) (35), in a study, reported similarity coefficients of 0.97 for the whole scale and a coefficient of 0.96 as test coefficients two or three days apart. Krobach's alpha coefficient of this scale was equal to 0.93 to provide an index for the validity of this scale; its correlation with the list of life events was calculated and reported as equal to 0.37, which indicates the concurrent validity of this scale.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by unpaired student's t-test.

4. Results

All of the participants are men. There was no significant difference in age between the control (15.9 ± 1.9) and experimental (15.8 ± 2.7) groups (P = 0.878).

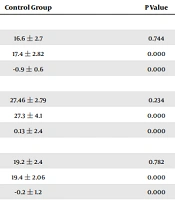

There is little difference between the pretest post-traumatic stress scores and their components in the two groups (Table 2). It is also observed that the mean post-traumatic stress scores and their components in the group posttest decreased compared to the pretest. Also, the mean post-traumatic stress scores and their components in the control group in the pretest and posttest were not significantly different. Before checking the significance of the observed differences using covariance analysis, the data's normality was checked using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and considering that the significance level for the variable was greater than 0.05, the null hypothesis indicates that the data is not normal. The normal distribution was confirmed. The results show a significant difference between the control and experimental groups (P < 0.05). In other words, "mindfulness-based stress reduction training has a significant effect on post-traumatic stress and its components."

| Experimental Group | Control Group | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Re-experience | |||

| Pretest | 16.9 ± 3.5 | 16.6 ± 2.7 | 0.744 |

| Post-test | 9.7 ± 2.5 | 17.4 ± 2.82 | 0.000 |

| Changes | 7.4 ± 3.11 | -0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.000 |

| Avoidance | |||

| Pretest | 25.6 ± 5.24 | 27.46 ± 2.79 | 0.234 |

| Post-test | 14.06 ± 5.03 | 27.3 ± 4.1 | 0.000 |

| Changes | 11.53 ± 4.6 | 0.13 ± 2.4 | 0.000 |

| Severe arousal | |||

| Pretest | 18.9 ± 4 | 19.2 ± 2.4 | 0.782 |

| Post-test | 11.8 ± 6 | 19.4 ± 2.06 | 0.000 |

| Changes | 7.1 ± 2.9 | -0.2 ± 1.2 | 0.000 |

| Post-traumatic stress | |||

| Pretest | 61.4 ± 9.6 | 63.2 ± 5.02 | 0.511 |

| Post-test | 35.46 ± 12.5 | 64.1 ± 4.7 | 0.000 |

| Changes | 25.9 ± 10.13 | -0.8 ± 3.1 | 0.000 |

Descriptive Statistics of Post-traumatic Stress by Group and Test Stage a

5. Discussion

Findings indicate that mindfulness-based stress reduction training at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic has effectively reduced post-traumatic stress in abused and unaccompanied adolescents of the correctional center. These results are in line with previous findings, which have shown that mindfulness exercises are an effective program for reducing stress that can be found in the research of Elahi et al. (18), Butler et al. (19), Hofmann and Gomez (20), Talebi (24), Eghbali, et al. (25), Naqibi et al. (26), Turkal et al. (29), van Son et al. (30), Mirzaee and Shairi (32) and Beyrami et al. (33).

Regarding the effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction training in reducing post-traumatic stress in abused and unaccompanied adolescents, it can be said that adolescents in the transition period from adolescence face various issues such as physical and sexual development, extreme emotions, identity search, fear of responsibility and some other challenging issues, each of which in turn can impose a lot of stress on adolescents. Therefore, due to the fact that mindfulness training helps people to know themselves better and experience a non-judgmental, accepting, trusting, patient and kind attitude, it causes people to become aware of relationships with others and the amount of contacts To increase their sociality, it will somehow be effective on interpersonal behaviors. In other words, it can be said that mindfulness training increases awareness of relationships, which in turn reduces post-traumatic stress (15).

Also, the effectiveness of mindfulness in improving post-traumatic stress can be explained by the fact that mindfulness includes the practice of components that lead patients to decentralization. In the mindfulness program, patients practice decentralization of thoughts and emotions (or anything else that may occur) during meditation sessions. These sessions enable a person to practice decentralization in a controlled environment, usually sitting with closed eyes in a relaxed atmosphere (36). Therefore, the focus of mindfulness training on intra-personal processes helps people change their relationships with their inner states, thoughts, and feelings, thus reducing post-traumatic stress.

5.1. Conclusions

Considering that unsupervised and abused teenagers are part of the vulnerable group of society, the use of the MBSR program and similar programs reduces excitement and anxiety, increases self-confidence, and thus prevents social harm.