1. Background

The construct of crime is difficult to define due to cultural variations (1, 2). It is legally described as intentional acts that violate criminal law, committed without defense, and penalized by the state (3). Traditional views on crime often face criticism for favoring powerful societal groups over moral norms (4). Crime manifests in various forms such as personal crimes (e.g., murder, robbery), property crimes (e.g., burglary, theft), consensual or victimless crimes (e.g., prostitution, illegal gambling), white-collar crimes (e.g., embezzlement, fraud), organized crimes (e.g., kidnapping, human trafficking), juvenile delinquency (crimes by those under 18), cybercrime (e.g., cyber terrorism, Internet fraud), and public safety violations (5).

Theorists often examine common traits among criminals when studying criminal behavior. Biological theories suggest that criminals are inherently predisposed to crime due to distinct biological characteristics. Sociological theories attribute criminal behavior to social opportunities and inequalities. Anthropological theories explore the influence of social relationships, class stratification, rapid social change, resource access, division of labor, colonized societies, power differentials, and wealth. Economic theories focus on cost-benefit analysis, proposing that individuals commit crimes when benefits surpass potential consequences. Psychological theories consider individualized and subjective factors such as cognition, personality, psychopathology, and positive reinforcement (1, 3-6).

Genetics and psychosocial variables both influence criminality. Men are more likely to commit crimes (1, 7). Psychopathy and sociopathy are also linked to criminal activity, particularly antisocial personality disorder (8, 9). Criminals exhibit chronic lying, lack of empathy, conditional love, blame-shifting, irresponsibility, intolerance, and poor self-control. Impulsivity, sensation-seeking, cognitive-social anxiety, antagonism, and violence are also common (10). Childhood environment, inconsistent love and discipline, physical abuse, maternal smoking during pregnancy, low birth weight, perinatal trauma, child neglect, low parental attachment, family discord, substance abuse in the family, poor parental supervision, large family size, birth order, bed-wetting, school disciplinary issues, low academic performance, dropping out of school, and childhood lead exposure all contribute to criminal behavior (7).

Criminal aptitude testing is essential in forensic psychology for identifying criminal inclinations. The existing literature lacks measures to test criminal aptitude in Urdu.

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to develop and validate the Criminal Aptitude Inventory (CAI) to fill this gap. Data was collected from both convicted prisoners and the general population. This dual-source data collection strategy, adapted in the series of four phases of the current study, strengthens and applies the CAI to other Urdu-speaking groups in Pakistan and India.

3. Methods

The present study involved three phases. Phase 1 focused on the development and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) of the CAI. Phase 2 involved the confirmatory factor analysis of the CAI. Phase 3 established the convergent and discriminant validity of the CAI.

3.1. Participants

The study involved 1675 participants across its three phases. Participants in phase 1 (n = 608; men = 66%; married = 37%; prisoners = 52%; age range = 18 - 73 years, M = 29; education range = 5 - 18 years formal education, M = 11), phase 2 (n = 956; men = 34%; married = 89%; prisoners = 4%; age range = 18 - 29 years, M = 21; education range = 10 - 20 years formal education, M = 14), and phase 3 (n = 111; men = 46%; married = 19%; age range = 18 - 51 years, M = 25; education range = 10 - 18 years formal education, M = 14) were conveniently selected while visiting different prisons and educational institutions in Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Haripur, and Attock, Pakistan.

3.2. Instruments

A new scale named the "Criminal Aptitude Inventory (CAI)" was developed. This scale consists of 36 items presented in Urdu, with responses recorded on a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. To assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the CAI, two established measures were employed: The Sukoon Moral, Religious, and Spiritual Intelligence Scale (this study) and the Anti-Social Personality Disorder Sub-Scale of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (Hyler et al., 1992).

3.3. Procedure

The study obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Review Committee at (the Department of Humanities at COMSATS University Islamabad, Islamabad Campus, Pakistan). Data was collected during October-November 2023. Researchers individually approached potential participants in various settings, including prisons, educational institutions, and public offices. Each participant received a detailed explanation of the study's purpose, and their informed consent to participate was obtained. The entire study adhered to ethical guidelines in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its subsequent amendments, ensuring the ethical conduct of research procedures.

3.4. Analysis

The analysis utilized SPSS and JASP software. Both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the instrument. Additionally, the Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the convergent and discriminant validity of the CAI.

4. Results

4.1. The Psychometric Properties of Criminal Aptitude Inventory (CAI)

In the initial development of the CAI, a total of 50 items were generated through three focus group discussions with 60 convicted prisoners, who shared their perspectives on criminality and criminals. Based on these discussions, 50 statements were formulated and submitted to a panel of 5 clinical psychologists for face validity assessment. The panel approved the statements, affirming their validity for measuring the construct of criminal aptitude. Data gathered in all four phases of the study was found reliable (Table 1).

| Variables | Items | α | Mean ± SD | % | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential | Actual | |||||||

| Phase 1 (n = 608) | ||||||||

| CAI | 36 | 0.984 | 66.923 ± 38.052 | 37.179 | 36 - 180 | 36 - 179 | 1.519 | 1.153 |

| Phase 2 (n = 956) | ||||||||

| CAI | 36 | 0.950 | 50.780 ± 17.463 | 28.211 | 36 - 180 | 38 - 176 | 3.762 | 19.178 |

| Phase 3 (n = 111) | ||||||||

| CAI | 36 | 0.882 | 58.216 ± 16.415 | 32.342 | 36 - 180 | 39 - 137 | 1.480 | 3.965 |

| Religious intelligence | 10 | 0.870 | 58.991 ± 9.254 | 84.273 | 10 - 70 | 15 - 70 | -1.707 | 4.478 |

| Spiritual intelligence | 6 | 0.799 | 31.622 ± 5.842 | 75.290 | 6 - 42 | 15 - 42 | -0.390 | -0.247 |

| Moral intelligence | 4 | 0.604 | 22.892 ± 3.262 | 81.757 | 4 - 28 | 13 - 28 | -0.393 | -0.072 |

| Anti-social personality disorder | 7 | 0.556 | 2.711 ± 1.775 | 38.728 | 0 - 7 | 0 - 7 | .90 | -0.783 |

Abbreviations: CAI, Criminal Aptitude Inventory; n, number of participants; α, Cronbach’s Alpha; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

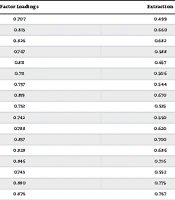

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Phase 1 employed principal component analysis with Varimax Rotation, concluding with a single-factor solution for 36 items (Table 2), discarding 14 items for having insufficient validity (item extraction values less than 0.4). The sample size (n = 608) for EFA was found to be excellent (KMO = 0.984), and the variance explained was 64.73%. Cronbach’s alpha reliability was 0.984. Communalities for all items were acceptable, ranging from 0.42 to 0.77 (Table 2). Item-total correlations were highly significant for all items, affirming their relationship with the overall scale (Table 2).

| Item No. | Factor Loadings | Extraction | Item-Total r b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.707 | 0.499 | 0.710 |

| 2 | 0.813 | 0.660 | 0.812 |

| 3 | 0.826 | 0.682 | 0.823 |

| 4 | 0.767 | 0.588 | 0.767 |

| 5 | 0.811 | 0.657 | 0.809 |

| 6 | 0.711 | 0.506 | 0.715 |

| 7 | 0.737 | 0.544 | 0.739 |

| 8 | 0.819 | 0.670 | 0.817 |

| 9 | 0.732 | 0.535 | 0.733 |

| 10 | 0.742 | 0.550 | 0.740 |

| 11 | 0.788 | 0.620 | 0.789 |

| 12 | 0.837 | 0.700 | 0.837 |

| 13 | 0.828 | 0.686 | 0.828 |

| 14 | 0.846 | 0.716 | 0.845 |

| 15 | 0.743 | 0.552 | 0.745 |

| 16 | 0.880 | 0.775 | 0.878 |

| 17 | 0.876 | 0.767 | 0.874 |

| 18 | 0.751 | 0.563 | 0.751 |

| 19 | 0.829 | 0.687 | 0.826 |

| 20 | 0.761 | 0.580 | 0.759 |

| 21 | 0.821 | 0.675 | 0.821 |

| 22 | 0.842 | 0.710 | 0.842 |

| 23 | 0.805 | 0.648 | 0.805 |

| 24 | 0.817 | 0.667 | 0.818 |

| 25 | 0.876 | 0.767 | 0.876 |

| 26 | 0.799 | 0.638 | 0.801 |

| 27 | 0.825 | 0.681 | 0.822 |

| 28 | 0.811 | 0.658 | 0.812 |

| 29 | 0.877 | 0.769 | 0.875 |

| 30 | 0.870 | 0.756 | 0.868 |

| 31 | 0.852 | 0.726 | 0.849 |

| 32 | 0.881 | 0.776 | 0.879 |

| 33 | 0.854 | 0.730 | 0.855 |

| 34 | 0.816 | 0.666 | 0.818 |

| 35 | 0.684 | 0.468 | 0.689 |

| 36 | 0.655 | 0.429 | 0.662 |

a Extraction method: Principal component analysis; rotation method, varimax with kaiser normalization.

b Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Phase 2 involved 956 participants to test the 36-item single-factor solution. The factor loadings were statistically significant (Table 3 P < 0.01), indicating strong item relationships with the original factor. A heterotrait-monotrait ratio of 1 suggested good discriminant validity. Reliability was also high, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.950. The CFA model demonstrated good fit according to several fit indices, including Comparative Fit Index (CFI): 0.936; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI): 0.932; Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI): 0.932; Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI): 0.904; Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI): 0.852; Bollen's Relative Fit Index (RFI): 0.898; Bollen's Incremental Fit Index (IFI): 0.936; Relative Noncentrality Index (RNI): 0.936; Goodness of Fit Index (GFI): 0.939; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA): 0.043; and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test: 0.980.

| Item | Factor Loadings | Residual Variances | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | z | P | Estimate | SE | z | P | |

| 1 | 0.343 | 0.026 | 13.236 | < 0.001 | 0.564 | 0.026 | 21.698 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 0.393 | 0.018 | 21.520 | < 0.001 | 0.233 | 0.011 | 21.337 | < 0.001 |

| 3 | 0.436 | 0.018 | 24.054 | < 0.001 | 0.211 | 0.010 | 21.149 | < 0.001 |

| 4 | 0.430 | 0.021 | 20.222 | < 0.001 | 0.327 | 0.015 | 21.415 | < 0.001 |

| 5 | 0.471 | 0.021 | 22.904 | < 0.001 | 0.282 | 0.013 | 21.241 | < 0.001 |

| 6 | 0.452 | 0.028 | 16.408 | < 0.001 | 0.601 | 0.028 | 21.596 | < 0.001 |

| 7 | 0.384 | 0.030 | 12.701 | < 0.001 | 0.773 | 0.036 | 21.713 | < 0.001 |

| 8 | 0.467 | 0.023 | 20.627 | < 0.001 | 0.368 | 0.017 | 21.394 | < 0.001 |

| 9 | 0.489 | 0.025 | 19.929 | < 0.001 | 0.439 | 0.020 | 21.435 | < 0.001 |

| 10 | 0.482 | 0.022 | 21.927 | < 0.001 | 0.334 | 0.016 | 21.315 | < 0.001 |

| 11 | 0.413 | 0.025 | 16.340 | < 0.001 | 0.508 | 0.024 | 21.599 | < 0.001 |

| 12 | 0.459 | 0.022 | 20.599 | < 0.001 | 0.356 | 0.017 | 21.395 | < 0.001 |

| 13 | 0.523 | 0.021 | 24.805 | < 0.001 | 0.278 | 0.013 | 21.088 | < 0.001 |

| 14 | 0.527 | 0.025 | 21.485 | < 0.001 | 0.421 | 0.020 | 21.333 | < 0.001 |

| 15 | 0.361 | 0.036 | 9.938 | < 0.001 | 1.155 | 0.053 | 21.774 | < 0.001 |

| 16 | 0.560 | 0.021 | 26.465 | < 0.001 | 0.261 | 0.012 | 20.913 | < 0.001 |

| 17 | 0.546 | 0.018 | 30.388 | < 0.001 | 0.153 | 0.008 | 20.325 | < 0.001 |

| 18 | 0.532 | 0.023 | 22.677 | < 0.001 | 0.371 | 0.017 | 21.264 | < 0.001 |

| 19 | 0.499 | 0.017 | 29.070 | < 0.001 | 0.151 | 0.007 | 20.571 | < 0.001 |

| 20 | 0.535 | 0.018 | 30.308 | < 0.001 | 0.149 | 0.007 | 20.348 | < 0.001 |

| 21 | 0.481 | 0.024 | 19.898 | < 0.001 | 0.428 | 0.020 | 21.437 | < 0.001 |

| 22 | 0.527 | 0.020 | 26.521 | < 0.001 | 0.229 | 0.011 | 20.912 | < 0.001 |

| 23 | 0.481 | 0.025 | 19.037 | < 0.001 | 0.476 | 0.022 | 21.482 | < 0.001 |

| 24 | 0.481 | 0.028 | 17.456 | < 0.001 | 0.588 | 0.027 | 21.540 | < 0.001 |

| 25 | 0.455 | 0.023 | 19.429 | < 0.001 | 0.406 | 0.019 | 21.461 | < 0.001 |

| 26 | 0.484 | 0.024 | 19.820 | < 0.001 | 0.436 | 0.020 | 21.438 | < 0.001 |

| 27 | 0.522 | 0.019 | 26.915 | < 0.001 | 0.215 | 0.010 | 20.864 | < 0.001 |

| 28 | 0.517 | 0.022 | 23.693 | < 0.001 | 0.310 | 0.015 | 21.181 | < 0.001 |

| 29 | 0.489 | 0.018 | 26.420 | < 0.001 | 0.200 | 0.010 | 20.921 | < 0.001 |

| 30 | 0.538 | 0.019 | 28.760 | < 0.001 | 0.183 | 0.009 | 20.614 | < 0.001 |

| 31 | 0.504 | 0.019 | 26.798 | < 0.001 | 0.203 | 0.010 | 20.877 | < 0.001 |

| 32 | 0.535 | 0.019 | 27.489 | < 0.001 | 0.211 | 0.010 | 20.770 | < 0.001 |

| 33 | 0.494 | 0.026 | 18.898 | < 0.001 | 0.512 | 0.024 | 21.488 | < 0.001 |

| 34 | 0.511 | 0.027 | 18.892 | < 0.001 | 0.547 | 0.025 | 21.486 | < 0.001 |

| 35 | 0.394 | 0.031 | 12.923 | < 0.001 | 0.784 | 0.036 | 21.706 | < 0.001 |

| 36 | 0.270 | 0.040 | 6.664 | < 0.001 | 1.477 | 0.068 | 21.824 | < 0.001 |

a Extraction was performed using the Maximum-likelihood extraction technique with no rotation. Average variance extracted was 0.350.

4.4. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

In phase 3, the CAI was tested for convergent and discriminant validity. The CAI revealed a significant positive correlation with antisocial personality disorder (r = 0.458; P < 0.01) and significantly inverse correlations with morality (r = -0.396; P < 0.01), religiosity (r = -0.318; P < 0.01), and spirituality (r = -0.453; P < 0.01).

Overall, the findings from the validation indicate that the CAI is sufficiently reliable and valid for further use in assessing criminal aptitude.

4.5. Additional Findings

The contrast in criminal aptitude between prisoners and the general population was highly significant, showing a large effect size (Table 4 M = 85.50 vs 46.68; P = 0.000; Cohen’s d = 1.185). Additionally, a notable difference in criminal aptitude was observed between men and women, with men exhibiting significantly higher levels and a large effect size (Table 3 M = 77.90 vs 45.64; P = 0.000; Cohen’s d = 0.925). The distinction in criminal aptitude between married and unmarried individuals was also statistically significant, though with a small effect size (Table 3 M = 72 vs 63.89; P = 0.011; Cohen’s d = 0.214). Furthermore, individuals with insufficient monthly income demonstrated a significantly higher level of criminal aptitude, indicating a large effect size (Table 3 M = 79.18 vs 55.45; P = 0.000; Cohen’s d = 0.655).

| Category | N | M | t(606) | P-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criminal tendencies | 0.000 | 1.185 | |||

| Prisoners | 317 | 85.505 ± 43.761 | 14.599 | ||

| General | 291 | 46.680 ± 12.467 | |||

| Gender | 0.000 | 0.925 | |||

| Men | 401 | 77.905 ± 42.468 | 10.809 | ||

| Women | 207 | 45.647 ± 8.653 | |||

| Marital status | 0.011 | 0.214 | |||

| Married | 227 | 72.009 ± 38.813 | 2.556 | ||

| Single | 381 | 63.892 ± 37.314 | |||

| The level of income | 0.000 | 0.655 | |||

| Low income | 294 | 79.187 ± 43.929 | 8.070 | ||

| Moderate income | 313 | 55.454 ± 27.023 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

5. Discussion

In forensic psychology, evaluating criminal aptitude is essential for determining whether an individual has a tendency toward criminal behavior. Existing literature lacked methods to evaluate criminal aptitude in Urdu, despite its great relevance. This study aimed to fill this gap through the development and validation of the CAI.

The development and validation process was carried out in three phases. The CAI was developed and then subjected to EFA during the first phase. The second phase involved confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and the third phase established the convergent and discriminant validity of the CAI. A total of 1279 individuals participated in the study across all three phases, including both incarcerated inmates and members of the general population.

The CAI measures criminal aptitude based on common factors that lead individuals toward criminal behavior. The items of the CAI address poverty, joblessness, immorality, violence, purposelessness, bad company, childhood experiences, rejection, loneliness, narcissism, envy, abuse, erroneous beliefs, drug addiction, injustice, and cognitive dissonance. All these factors have been regarded as significant contributors to criminal behavior (1, 3-6).

5.1. Implications

The CAI plays a vital role for prison psychologists by enabling them to monitor the progress of criminal aptitude during psychosocial rehabilitation programs. It can also serve as a comparative measure to assess the efficacy of correctional programs. Additionally, the CAI provides a foundation for future investigations in Pakistan and other regions where Urdu is spoken, such as India.

5.2. Conclusions

The CAI, developed and validated in this study, is an effective tool for measuring criminal tendencies in Urdu-speaking communities. The rigorous psychometric evaluations performed ensure the reliability and validity of the CAI. The CAI has tremendous potential for use in various forensic and psychological contexts, assisting law enforcement and psychological examinations in detecting and addressing criminal behavior tendencies.