1. Background

Technological advancements have transformed industries, particularly education. The rapid global shift has led to an increased adoption of online learning, with e-learning experiencing significant growth, especially due to the coronavirus pandemic. This shift has raised concerns about the quality of online education (1, 2).

Learning management systems (LMS) are also referred to as "learning platforms," "distributed learning systems," "course management systems," "content management systems," and "portals" (3). Since LMS is web-based, it supports education, learning, management, and development processes (1). The primary goal of every LMS is to provide a learning environment for students based on the concept of "anywhere and anytime" (4). Additionally, the various features of LMS can assist in managing and presenting content, facilitating collaboration, and enhancing communication among teachers, between teachers and learners, and among learners themselves (5).

Some studies have criticized LMS for changing learning methods (6), its designed structure (7), usability and reliability (4, 8), limited interaction, and its teacher-centered approach (7), as well as the design characteristics in terms of support for all users of the system (9) have criticized education and training (7, 10). Others have pointed out that LMS can limit opportunities for social and informal learning and reduce the potential for enhancing teaching and learning (11, 12). Numerous studies indicate that simply combining new software and technology with basic elements, without understanding their environment, fails to achieve quality education (13). Students' experiences and preferences greatly influence the success of virtual education through the learning management system. Similarly, professors' proficiency and willingness to use the Learning management system affect students' satisfaction and engagement with online learning (9).

Numerous studies have examined various factors affecting students' satisfaction with LMS systems, and the results have shown that the level of learners, instructors, training courses, technology, system design, learning environment, social factors (such as supportive factors, inclusive perspective, and instructor's attitude), and technical aspects of the system (including system, information, and service quality) all influence satisfaction levels (1, 14, 15).

The next generation of LMS is expected to be more personalized, social, flexible, and supportive of learning analytics to maximize platform benefits and enhance learning (1, 2).

Given the importance of e-learning in education and its potential to improve performance, enhancing virtual education is essential. Professional guidelines emphasize the need for quality in educational institutions. Despite the increase in virtual education, some institutions continue to rely on existing platforms for training due to their specific missions and security requirements, making the evaluation of these platforms crucial.

2. Objectives

This study aims to assess the satisfaction of professors and students with the learning management system and the quality of virtual education at a university during the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on their experiences and preferences for effective implementation.

3. Methods

This descriptive study was conducted from March 2021 to June 2022. The inclusion criteria encompassed all professors and students actively participating in the virtual education process, which involved attending university classes as students and teaching in virtual classes as professors. According to the Morgan Table, and allowing for a 10% drop rate, 66 questionnaires were distributed to professors and 216 to students using a convenience sampling method. Out of the distributed questionnaires, 44 completed ones from professors and 167 from students were included in the analysis, which was conducted using SPSS version 22 software.

To assess the research objectives and evaluate professors' satisfaction with virtual teaching and the user interface, a demographic profile and three questionnaires were used to gather student opinions on the quality of virtual education. The professors' surveys included demographic information and user interface satisfaction. The demographic form collected data on age, gender, teaching experience, faculty, academic degree, content preparation method, LMS experience, and content delivery method. The survey on professors' virtual teaching included 20 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1, completely disagree, to 5, completely agree). Items 7 and 14 were scored inversely. To determine the level of satisfaction with virtual teaching, the scale was defined as follows: 30% to 33% indicated dissatisfaction, 34 to 67% indicated average satisfaction, and above 68% indicated desirable satisfaction.

To assess user satisfaction (professors and students) with the learning management system interface, the 77-question QUIS questionnaire was utilized. This questionnaire covers four areas: Screen (24 items), terms and information of the system (13 items), learning (28 items), and general perceptions (10 items), all rated on a 9-point Likert scale. The total score obtainable from the questionnaire was 693. Based on the scale, scores between 1 and 231 indicate user dissatisfaction with the system, 232 to 462 indicate satisfaction, and above 463 are considered in the desirable range. This questionnaire has been used in various studies in Iran and is recognized for its good validity and reliability (16).

To assess the demographic characteristics of the students, information was collected on age, gender, faculty, field of study, level of education, and mode of class participation. The questionnaire for evaluating professors' performance in virtual teaching from the students' perspective consisted of 12 items with 5 options (1 = completely disagree, 5 = completely agree). According to the 33% rule, scores between 1 and 20 indicate poor performance, scores from 21 to 40 indicate average performance, and scores from 41 to 60 indicate desired performance. The reliability of this questionnaire has been reported as 0.89 (17).

The questionnaire on the quality of the virtual education course included 16 items with 5 options (1 = completely agree, 5 = completely disagree). Items 10 and 12 on this questionnaire have reverse scoring. Based on the 33% rule, a score of 1 to 26 indicates poor quality of education, while scores from 27 to 53 indicate average or higher quality. The reliability of these questionnaires has been reported as 0.88 and 0.91, respectively (18).

To explore the relationship between age and professors' virtual teaching performance, Pearson's correlation coefficient was used along with independent t-tests and ANOVA. Additionally, a multivariate analysis investigated how age, gender, faculty type, and tools used by students correlate with professors' quality scores, virtual education quality, and four dimensions of student satisfaction. Pillai's Trace statistic was employed in the multivariate analyses due to its robustness. Approval from the ethics committee with code IR.BMSU.REC.1399.480 was obtained before the study, and all participants provided informed consent.

4. Results

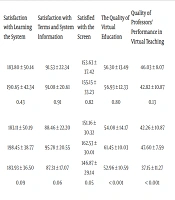

The average age of the students was 21.23 ± 2.78 years, with 81.8% (135) being male. Of the students, 40% (66) were from nursing, 40.6% (67) from medicine, and 19.4% (32) from pharmacy. Participation in virtual classes included 53.9% (89) via mobile, 29.7% (49) via laptop, and 16.4% (27) using both devices. Student satisfaction with the learning management system averaged 497.21 ± 109.68; 57% reported optimal satisfaction, and 40.6% reported average satisfaction. The average score for professors' performance was 43.18 ± 9.98, while the quality of virtual education was rated at 58.81 ± 12.51, with 68% of students reflecting an average quality. Satisfaction with the system interface was segmented into the screen (58.2%), system terms (56.4%), learning (49.7%), and overall perceptions (50.3%). Tukey's test showed that pharmacy professors scored lower than medical (P = 0.04) and nursing professors (P < 0.001), while nursing professors outperformed both medical (P < 0.006) and pharmacy professors (P < 0.001). No significant differences were found in the quality of virtual education between medicine and pharmacy (P = 0.9), but nursing scores were higher than those for medicine (P < 0.001) and pharmacy (P = 0.004). Scores for teaching performance, education quality, and satisfaction did not differ significantly by gender (Table 1), nor did age correlate with these performance metrics (r = 0.01, P = 0.86). However, students using mobile devices scored higher than those using both devices (P < 0.001). The box test suggested that multivariate normality and equality of variance-covariance were not upheld (P < 0.001), but equal variances for performance quality (P = 0.11) and education quality (P = 0.42) were maintained, along with user satisfaction across four dimensions: Screen (P = 0.40), terms (P = 0.36), learning (P = 0.70), and general perception (P = 0.30).

| Variables | Satisfaction with Public Perceptions | Satisfaction with Learning the System | Satisfaction with Terms and System Information | Satisfied with the Screen | The Quality of Virtual Education | Quality of Professors' Performance in Virtual Teaching |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 59.93 ± 19.62 | 183.80 ± 50.14 | 91.53 ± 22.34 | 153.63 ± 37.42 | 56.30 ± 13.49 | 46.03 ± 8.07 |

| Male | 62.16 ± 19.44 | 190.65 ± 42.34 | 91.08 ± 20.61 | 155.15 ± 33.23 | 56.93 ± 12.33 | 42.82 ± 10.87 |

| P-value | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.13 |

| College | ||||||

| Medicine | 59.07 ± 19.62 | 183.11 ± 50.19 | 88.46 ± 22.20 | 151.16 ± 30.32 | 54.08 ± 14.17 | 42.26 ± 10.87 |

| Nursing | 64.74 ± 19.09 | 198.45 ± 38.77 | 95.78 ± 20.55 | 162.53 ± 30.01 | 61.45 ± 10.03 | 47.60 ± 7.59 |

| Pharmacology | 61.21 ± 19.47 | 183.93 ± 36.50 | 87.31 ± 17.07 | 146.87 ± 29.14 | 52.96 ± 10.59 | 37.15 ± 11.27 |

| P-value | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Class participation tool | ||||||

| Mobile | 61.61 ± 20.62 | 187.29 ± 46.39 | 91.56 ± 21.04 | 156.24 ± 33.30 | 58.56 ± 11.68 | 46.10 ± 8.42 |

| Laptop | 62.06 ± 16.98 | 192.06 ± 41.71 | 90.91 ± 19.85 | 153.36 ± 33.77 | 55.85 ± 14.02 | 41.89 ± 12.47 |

| Both | 61.66 ± 20.27 | 191.59 ± 39.47 | 90.33 ± 22.77 | 153.11 ± 37.19 | 52.81 ± 11.54 | 37.29 ± 9.84 |

| P-value | 0.99 | 0.79 | 0.96 | 0.85 | 0.09 | < 0.001 |

The Average Performance Scores of Professors in Virtual Teaching, the Quality of Virtual Education and the Dimensions of the Learning Management System a

The analysis found no significant relationship between gender (P = 0.35) or age (P = 0.92) and students' perceptions of virtual teaching quality. However, class participation tools showed significant differences across faculties (P < 0.001; Pillai's Trace = 0.11; eta squared = 0.06), with Bonferroni correction indicating differences in professors' performance (P < 0.001) and virtual education quality (P = 0.005). Multivariate analysis revealed no significant links between gender (P = 0.69), age (P = 0.40), faculty type (P = 0.20), or tool used (P = 0.76) and user satisfaction with the LMS. Among the 18 assistant professors, 61% were male, and 41% used PowerPoint only. Most (93.2%) had experience with virtual education. Satisfaction with the LMS interface showed that 29.5% were dissatisfied, while 70.5% were moderately satisfied. No significant relationships were found between LMS dimensions and gender or satisfaction, but satisfaction was correlated with the screen (P = 0.012) and system information (P = 0.042), influenced by experience and discipline, with age also correlating with screen satisfaction (P = 0.028).

5. Discussion

The results indicated that over half of the students were satisfied with the learning management system interface. The performance of professors in virtual education was generally rated as average, with the nursing faculty receiving notably higher satisfaction ratings. Overall, student satisfaction with virtual education was also rated as average. Satisfaction with the LMS interface was evaluated in four areas: Screen, terms, system information, and general impressions, with half of the students achieving the desired satisfaction level. University professors reported similar average satisfaction levels with both the LMS and virtual education. However, about one-third were dissatisfied with the LMS interface, and their overall satisfaction with virtual teaching was also average.

In one study, medical students expressed high satisfaction with the LMS system's clarity, ease of use, and training (19). Another study found that LMS satisfaction depended on IT quality, service quality, ease of use, and usefulness (20). One study reported that over half of the students were dissatisfied with LMS training due to a lack of animation, multimedia, slow internet, and content-sharing issues (21). Satisfaction with e-learning is heavily influenced by the quality of LMS information, which should be relevant, clear, and up-to-date. This quality is primarily determined by the course designer. Additionally, students' readiness for online learning, assessed through their basic computer and internet skills, also significantly impacts their satisfaction (22). These findings from previous research suggest that the ability to use LMS and the availability of technical assistance are strongly related to students’ satisfaction (13).

A survey revealed that students rated the technical quality of the LMS positively, particularly noting the fast uploading of files and online tests. However, this study found dissatisfaction due to a lack of support for different file types and the Persian language (23). Another study identified insufficient learning resources, ambiguous materials, and poor LMS learning as problems in distance education (13). One study showed that continuous use and the initial decision to use LMS depend on personal perceptions about technology and mental norms (24).

The research results showed that attitudes toward LMS acceptance and students' characteristics positively affect the intention to adopt LMS and effective LMS learning during the COVID-19 period. Additionally, certain management strategies can be employed to further increase students' intention to adopt LMS (24-27).

Students reported higher satisfaction with virtual classes accessed via mobile devices on the learning management system. This aligns with other studies that highlight mobile use for its flexibility and cost-effectiveness (28, 29). Important influencing factors include self-efficacy, innovation, perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness of the mobile LMS, and external factors such as social norms (30).

The results indicated no significant relationship between students' demographic characteristics (such as gender and age) and their satisfaction with the learning management system. Satisfaction levels were similar for both male and female students. However, different age groups showed varying levels of satisfaction with the system's quality features. The importance placed on these features also varied based on the length of Moodle usage. Notably, female students prioritized aspects like average response time, feedback quality, content accuracy and clarity, website user-friendliness, collaboration diversity, and the quantity of material (31). The study found no correlation between system satisfaction and educational methods or content type (32).

The study indicated moderate overall satisfaction with the quality of teaching and virtual LMS education. It was found that professors' age significantly affected their satisfaction with screen use, while another study reported no such correlation between age and satisfaction with educational technologies (9). In one study, educational experts assessed the educational management system and rated the quality of content, classes, interaction, and technical aspects as higher than 50% (13). Experts suggest that education can continue without physical presence and emphasize the need for the rapid development of electronic infrastructures. University authorities should facilitate the adaptation process for both faculty and students (33).

This study was conducted at a university center with a limited pool of students and professors, which reduces its generalizability to other institutions. Sampling was convenient due to the absence of students during the coronavirus pandemic. A strength of the study was the use of a valid and comprehensive questionnaire to assess the user interface, providing valuable insights for the center's managers. To enhance system success and user satisfaction, it is essential to implement comprehensive measures addressing content features, system-user interaction, and related interventions.

5.1. Conclusions

To improve virtual education, it is crucial to enhance the LMS system, refine content preparation, and adopt engaging teaching methods that motivate students. Focusing on these areas can significantly improve the quality of virtual learning.