1. Context

Neuropathic pain — a persistent pain resulting from the direct impact of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system — affects millions worldwide. Neuropathic pain can be caused by various factors, such as diabetes, Guillain-Barré syndrome (peripheral), multiple sclerosis and stroke (central), and trauma (which can be either peripheral or central). Although neuropathic pain affects 3% to 17% of the general population, it accounts for more than 50% of patients referred to pain clinics (1-3). It is essential to distinguish between neuropathic pain and other types of pain, as they have different etiologies. While other types of pain may be related to inflammation, neuropathic pain is caused by damage or dysfunction of the nervous system. Treatment approaches also differ, as antidepressants are ineffective for other types of pain but can be used for neuropathic pain. Additionally, the prognosis may vary, ultimately impacting a person's quality of life. Therefore, it is crucial to differentiate between these types of pain (4-7).

Several diagnostic methods are available to confirm sensory system diseases or neuropathic pain. These methods include clinical neurological examination, electromyography, MRI, laboratory findings, and quantitative sensory tests. Despite their usefulness, these methods are not widely accepted due to the lack of standardized criteria and their time-consuming nature in clinical settings (8, 9). Therefore, to screen for neuropathic pain, researchers have developed questionnaires (10). While these questionnaires may not be accurate enough to make a definitive diagnosis, they can serve as a starting point for further evaluation with more precise tools. If the screening questionnaire indicates the presence of neuropathic pain, patients can then undergo further testing (11, 12).

The DN4 is one of the six questionnaires recommended by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) for neuropathic pain screening. It has been translated into several languages and culturally adapted. The DN4 includes ten items: Seven sensory descriptors and three items related to the presence of pain-related signs (8, 13). The DN4 Questionnaire has gained attention due to its reliability and validity (14), diagnostic accuracy (15), ease of use (16, 17), specificity (14), and effectiveness in identifying pain related to peripheral diabetic polyneuropathy (18, 19). Researchers have used the DN4 to stratify possible and definite postsurgical peripheral neuropathic pain and have validated the interview part of the DN4 (DN4i) for screening neuropathic pain (20).

In clinical settings, a clear consensus is necessary regarding the validity, reliability, and optimal cut-off point of the DN4 Questionnaire to differentiate neuropathic pain.

2. Objectives

This systematic review aims to evaluate the validity and reliability of the DN4 Questionnaire in diagnosing and differentiating neuropathic pain from other types of pain through a comprehensive review of the available literature on the DN4 Questionnaire. The findings of this study provide insights into the clinical application of the DN4, enabling clinicians to select personalized and appropriate pain treatments for their patients and make better-informed decisions.

3. Evidence Acquisition

3.1. Literature Search

We conducted the meta-analysis following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (21). Additionally, a systematic search of international databases — PubMed/Medline, Embase, Scopus, Science Direct, Cochrane, and Web of Science — and Persian databases — Magiran, IranMedex, IranDoc, and SID — as well as Google Scholar, was performed by two independent researchers up to May 2021. The following terms were used: "Douleur Neuropathique 4", "DN4", "Neuropathic Pain Questionnaire", "Validity", "Reliability", "Sensitivity", "Specificity", "Cut-off point", "Repeatability", and "Diagnosis". The PubMed search query is provided in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File. All project information was registered on the PROSPERO website, which is dedicated to the registration of systematic review studies, and the confirmation code CRD42021251336 was received. Additionally, this thesis was reviewed and approved by the code of ethics IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.150 at the Faculty of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences.

3.2. Study Selection

Studies that utilized the DN4 Questionnaire, examined individuals over 18 years old, reported the validity or reliability, sensitivity or specificity of the questionnaire, were published until May 2021, and were written in Persian or English were included. Excluded studies comprised case reports, narrative reviews, systematic reviews with or without meta-analyses, animal studies, case series, study protocols, scoping reviews, books and book chapters/sections, retrospective chart reviews, cohorts, and cross-sectional studies. Additionally, conference or meeting abstracts that did not provide usable data were excluded.

Each researcher entered the retrieved articles into Thomson Reuters EndNote version 20.3, and duplicate studies were removed. The studies obtained from searches conducted by two independent researchers were merged, and duplicate items were removed again. Two independent researchers conducted an initial review of titles and abstracts, followed by a second review based on full-text articles when clarification of relevance was needed. If the full text of a study was unavailable, the corresponding author was contacted via email to request the full text. If no response was received, the article was excluded. Additionally, researchers manually searched the reference lists of included articles to identify additional eligible studies.

Any disagreements between the two independent researchers at any stage were resolved through discussion or based on the principal researcher's opinion.

3.3. Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from each included study and recorded in an Excel sheet: Author's name, year of publication, country, mean age of participants, total number of participants, number of neuropathic patients, the specific disease evaluated, reference for neuropathic patient diagnosis (assessor), reliability measures (Cronbach's alpha, intraclass correlation coefficient), and validity measures (area under the curve, sensitivity, specificity, and optimal cut-off point).

All data were independently extracted in duplicate by two researchers. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus. If additional information was required, the corresponding author was contacted via email.

3.4. Interpretation

We have reported the total sum for certain variables and provided a range for others due to methodological variations among the eligible studies and the nature of the variables analyzed. For numerical variables extracted from the included studies, such as the total number of participants and the number of confirmed neuropathic patients, the sum was calculated. For variables such as mean age, reliability (internal consistency measured by Cronbach's alpha and test-retest reliability measured by the intraclass correlation coefficient), and validity [area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity of the DN4 Questionnaire in both its 10-item and 7-item versions], the range of values was determined.

Other variables that could not be quantified within a range, such as the types of diseases causing neuropathic pain, were analyzed descriptively. The following classification was used to interpret the assessment properties of the included studies:

3.4.1. Reliability

Cronbach's alpha coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating greater internal consistency. The classification of this coefficient is as follows: Above 0.9 is considered excellent, between 0.7 and 0.9 is high, between 0.6 and 0.7 is moderate, between 0.5 and 0.6 is acceptable, and below 0.5 is classified as low (22).

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), with a 95% confidence interval, is also evaluated on a scale from 0 to 1. An ICC value greater than 0.70 is generally considered acceptable for assessing reliability (23).

3.4.2. Validity

The AUC, calculated using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, is a measure of test performance that is independent of the optimal cut-off point for sensitivity and specificity. The classification of AUC values is as follows: AUC ≤ 0.5 is considered "negative", 0.51 - 0.70 is "poor", 0.71 - 0.80 is "acceptable", 0.81 - 0.90 is "excellent", and values above 0.90 are classified as "outstanding" (24).

Sensitivity measures the proportion of individuals with neuropathic pain who are correctly identified by the questionnaire, while specificity measures the proportion of individuals without neuropathic pain who are correctly classified as such. The optimal cut-off point is determined to balance the highest sensitivity — ensuring that neuropathic patients are accurately identified — along with the highest specificity to minimize false-positive cases (25).

4. Results

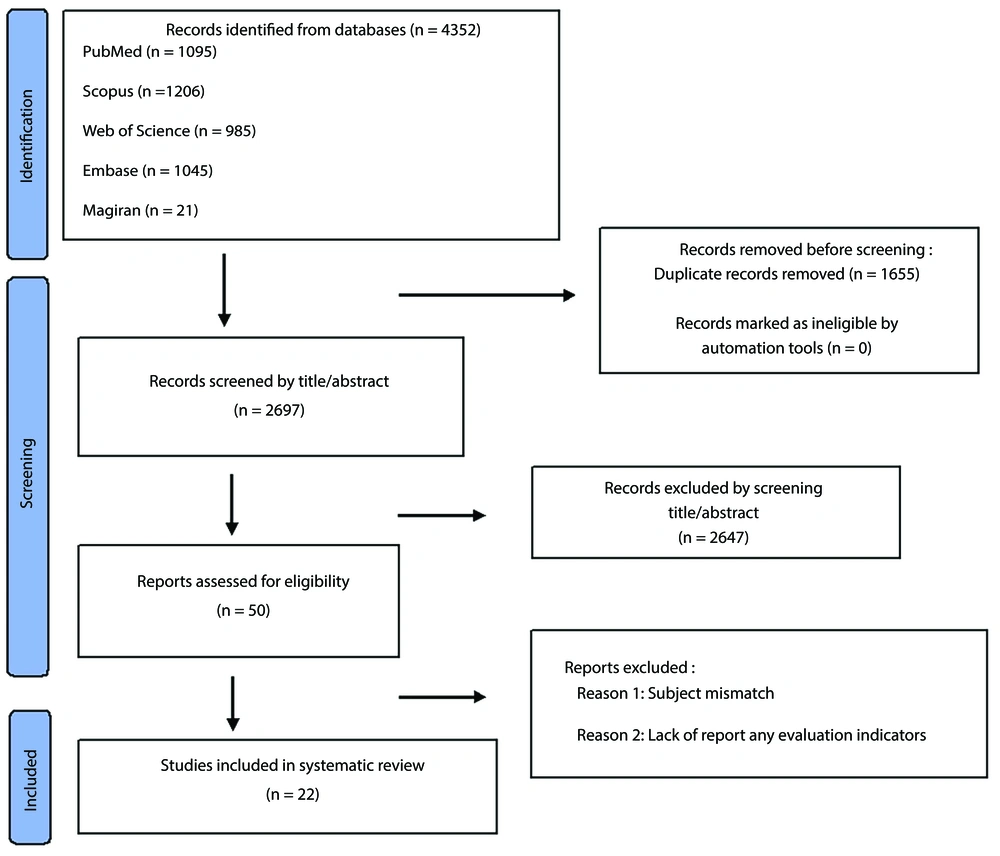

A total of 4,352 articles were identified through database searches. Initially, 1,655 duplicate articles were removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 2,697 studies were then screened for eligibility, leaving 50 studies for full-text review. Following the full-text assessment, 28 studies were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 22 studies were included in the data extraction phase (14, 16, 17, 19, 26-42). Additionally, no further articles were identified through a review of the reference lists of the included studies (Figure 1).

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the eligible studies. These studies evaluated the DN4 Questionnaire in various languages across different countries: Three studies in Dutch, two studies each in Italian, Arabic, and Spanish, and one study each in Chinese, Persian, Lebanese, French, Indian, Moroccan, Japanese, Greek, Korean, Turkish, Taiwanese, and English. Among the included articles, one study exclusively examined the 7-item DN4 Questionnaire (DN4-symptoms), four studies assessed both the 7-item and 10-item DN4 Questionnaires, while the remaining studies focused solely on the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire.

| Authors | Year | Country | Participants | Disease-Induced Neuropathic Pain | Neuropathic Pain Diagnosis Reference (Assessor) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Mean Age (y) | Neuropathic Pain Patients | |||||

| Wang et al. (26) | 2019 | Taiwan | 318 | - | 189 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Unal-Cevik et al. (17) | 2010 | Turkey | 180 | 51.79 | 121 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| van Seventer et al. (28) | 2013 | Netherlands | 248 | 52.3 | 85 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| VanDenKerkhof et al. (27) | 2018 | Canada | 789 | 53.5 | 789 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Spallone et al. (19) | 2011 | Italy | 158 | 53.57 | 97 | Diabetic neuropathy | Experts opinion |

| Saxena et al. (29) | 2021 | India | 285 | 51.1 | 153 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Sykioti et al. (30) | 2014 | Greece | 237 | 66.2 | 123 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Kim et al. (16) | 2016 | Korea | 83 | 62.51 | 43 | lumbar-radicular pain (degenerative spinal disease) | Experts opinion |

| Madani et al. (31) | 2014 | Iran | 175 | 52.53 | 86 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Matsuki et al. (32) | 2018 | Japan | 187 | 60.02 | 100 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Padua et al. (33) | 2013 | Italy | 392 | 58.8 | 255 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Perez et al. (34) | 2007 | Spain | 158 | 60.1 | 99 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Terkawi et al. (35) | 2017 | Saudi Arabia | 124 | 51.16 | 77 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Timmerman et al. (36) | 2017 | Netherlands | 228 | 55.74 | 170 | Low back and leg pain, neck-shoulder-arm-pain (NSAP) | Experts opinion |

| Abolkhair et al. (14) | 2021 | Saudi Arabia | 188 | 53.27 | 141 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Bouhassira et al. (13) | 2005 | France | 160 | 56 | 89 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Chatila et al. (37) | 2017 | Lebanon | 195 | 48.2 | 99 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Chen and Li (38) | 2016 | China | 170 | 59.67 | 100 | Diabetic neuropathy | Experts opinion |

| Epping et al. (39) | 2017 | Netherlands | 180 | 49.5 | 59 | Spinal radiculopathy | Experts opinion |

| Hallstrom and Norrbrink (40) | 2011 | Sweden | 40 | 49 | 28 | Spinal cord injury | Experts opinion |

| Hamdan et al. (41) | 2014 | Spain | 192 | 62.74 | 121 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

| Harifi et al. (42) | 2011 | Morroco | 170 | 49.5 | 94 | Variable diseases | Experts opinion |

Of the 22 included articles, six examined the DN4 Questionnaire for specific neuropathic pain conditions, four addressed spinal-related neuropathic pain, and the others evaluated the questionnaire for neuropathic pain conditions not associated with a specific disease. All studies classified neuropathic and non-neuropathic patients based on expert opinions, considered the gold standard for neuropathic pain diagnosis.

A total of 4,830 individuals participated in these studies, including both neuropathic and non-neuropathic patients. Among them, 3,118 were classified as neuropathic patients. The mean age of participants in the included studies ranged from 48.2 to 66.2 years.

Table 2 summarizes the assessment properties obtained from the eligible studies. The internal consistency for the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire ranged from 0.57 to 0.97. Two studies assessed the internal consistency of the 7-item DN4 Questionnaire, reporting values between 0.52 and 0.63. In studies that evaluated test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire, all studies (100%) reported an ICC above 80%, with six studies (66%) reporting an ICC of 90% or higher.

| Types of Questionnaire and Authors | Reliability | Validity | Optimal Cut-off Point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Consistency (Cronbach's Alpha) | Test-Retest-Reliability (Interclass Correlation Coefficient) | AUC | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | ||

| DN4 10-item | ||||||

| Wang et al. (26) | 0.7 | 0.83 | 77 | 78 | ≥ 3 | |

| Unal-Cevik et al. (17) | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 95 | 96.6 | ≥ 4 |

| van Seventer et al. (28) | 0.82 | 75 | 79 | ≥ 5 | ||

| VanDenKerkhof et al. (27) | 82.6 | |||||

| Spallone et al. (19) | 0.94 | 80 | 92 | 4 | ||

| Saxena et al. (29) | 0.82 | 0.95 | 0.82 | 78 | 76 | ≥ 3.5 |

| Sykioti et al. (30) | 0.65 | 0.956 | 0.919 | 92.7 | 78 | ≥ 4 |

| Kim et al. (16) | 0.819 | 0.813 | 0.953 | 100 | 88.20 | ≥ 3 |

| 87.10 | 94.10 | ≥ 4 | ||||

| Madani et al. (31) | 0.852 | 0.957 | 0.974 | 90 | 95 | ≥ 4 |

| Matsuki et al. (32) | 0.827 | 0.888 | 71 | 92 | ≥ 4 | |

| Padua et al. (33) | 82 | 81 | ≥ 4 | |||

| Perez et al. (34) | 0.71 | 0.95 | 0.85 | 79.80 | 78.00 | ≥ 4 |

| Terkawi et al. (35) | 0.67 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 88.31 | 74.47 | ≥ 4 |

| Timmerman et al. (36) | 0.57 | 0.84 | 0.829 | 75 | 76 | ≥ 4 |

| Abolkhair et al. (14) | 0.74 | 0.89 | 89 | 77 | ≥ 4 | |

| Bouhassira et al. (13) | 0.92 | 82.90 | 89.90 | ≥ 4 | ||

| Chatila et al. (37) | 0.99 | 0.94 | 97 | 82.30 | ≥ 3 | |

| Chen and Li (38) | 0.75 | 82.70 | 97.10 | ≥ 4 | ||

| Epping et al. (39) | 0.86 | 0.60 | 76 | 42 | ≥ 3 | |

| Hallstrom and Norrbrink (40) | 0.86 | 93 | 75 | ≥ 4 | ||

| Hamdan et al. (41) | 0.989 | 95.04 | 97.18 | ≥ 4 | ||

| DN4 7-item | ||||||

| Harifi et al. (42) | 0.63 | 0.962 | 0.88 | 89.40 | 72.40 | ≥ 3 |

| Chatila et al. (37) | 0.99 | |||||

| Timmerman et al. (36) | 0.52 | 0.85 | 0.713 | 70 | 67 | ≥ 3 |

| VanDenKerkhof et al. (27) | 81.4 | |||||

| van Seventer et al. (28) | 0.81 | 74 | 79 | ≥ 4 | ||

Abbreviation: AUC, area under the curve.

The AUC for both the 10-item and 7-item DN4 Questionnaires ranged from 0.6 to 0.989. Specifically, for the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire, the AUC followed the same overall range, while for the 7-item DN4 Questionnaire, it ranged between 0.94 and 0.713. Among the 10 studies that reported AUC values, 17 (94.4%) reported an AUC above 80%, and seven studies (38%) reported an AUC above 90%. Of the four studies assessing the validity of the 7-item DN4 Questionnaire through AUC, three (75%) reported an AUC above 80%.

In total, 22 studies reported the sensitivity index for the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire, while five studies reported sensitivity for the 7-item version, regardless of the specific cut-off point. Among the 10-item DN4 Questionnaires, sensitivity ranged from 71% to 100%. One study reported two optimal cut-off points for the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire, with a sensitivity of 100% at a cut-off of ≥ 3 and 87.1% at a cut-off of ≥ 4. The sensitivity for the 7-item DN4 Questionnaire (symptoms) ranged from 70% to 97%, irrespective of the specific optimal cut-off point.

Regarding specificity, 21 studies reported specificity values for the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire, while four studies reported specificity for the 7-item version. The specificity for the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire ranged from 42% to 97.18%, while for the 7-item DN4 Questionnaire, it ranged from 67% to 80%.

A total of 21 studies for the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire and four studies for the 7-item version reported the optimal cut-off points. Across all studies examining either the 10-item DN4 Questionnaire (complete) or the 7-item version (symptoms), the optimal cut-off points ranged from ≥ 3 to ≥ 5. The most frequently reported cut-off point for both versions was ≥ 4, with an overall frequency of 77%. Specifically, among the 10-item DN4 studies, 15 studies (71%) identified ≥ 4 as the optimal cut-off point, while among the 7-item DN4 studies, two studies (50%) reported the same cut-off point.

5. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the validity and reliability of the DN4 Questionnaire in diagnosing and differentiating neuropathic pain from other types of pain through a comprehensive review of the available literature.

Following an extensive literature search across multiple databases, 22 studies were included for analysis. These studies examined the reliability (internal consistency and intraclass correlation coefficient) and validity (area under the curve, sensitivity, and specificity with an optimal cut-off point) of the DN4 neuropathic pain questionnaire in 16 languages. The total sample included 4,830 participants, of whom 3,118 were diagnosed with neuropathic pain.

The findings indicate that the DN4 Questionnaire is a reliable and valid tool for identifying neuropathic pain when used alongside other diagnostic methods. It is not intended to serve as a standalone diagnostic tool but rather as a screening aid for patients requiring further evaluation. The questionnaire demonstrates acceptable levels of internal consistency, test-retest reliability, diagnostic accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

In all studies, the test-retest reliability of both the 10-item and 7-item DN4 Questionnaires had a minimum ICC value of 0.7, indicating acceptable reliability. Regarding internal consistency, most studies reported Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.7 for the 10-item version, supporting its reliability. However, three studies reported values below 0.7 for the 10-item form, while the 7-item questionnaire did not meet this threshold in any study.

The results showed that the DN4 Questionnaire generally falls within the "excellent" or "outstanding" range for the AUC, with the exception of one study focusing on patients with spinal radiculopathy (39). These findings suggest that both the 10-item and 7-item versions of the DN4 Questionnaire are appropriate for assessing neuropathic pain based on this metric. Additionally, these results align with those of the original French version of the DN4 Questionnaire (13).

The studies demonstrated satisfactory diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for both the 10-item and 7-item questionnaires, further confirming their validity. The optimal cut-off point balancing sensitivity and specificity ranged from ≥ 3 to ≥ 5. Most studies across various languages and cultural contexts consistently identified ≥ 4 as the optimal cut-off, a finding consistent with the original French version (13).

Although Mathieson et al.’s study initially yielded similar results to ours regarding the measurement properties of the included studies, the methodological quality of the selected articles influenced the final interpretation. Unlike our approach, Mathieson et al. factored methodological limitations into their final conclusions, leading to different interpretations. The low methodological quality of the included articles significantly impacted their assessment, resulting in less favorable conclusions in Mathieson et al.'s study (11). Mathieson et al. argued that due to the poor methodological quality of the selected articles, which had a substantial effect on the findings, it was not possible to accurately determine the reliability of these questionnaires in distinguishing neuropathic pain from non-neuropathic pain. However, they concluded that despite these limitations, the DN4 Questionnaire could still serve as a useful tool for identifying patients who require further evaluation for neuropathic pain in clinical settings (11).

Our study demonstrates that the overall validity and reliability of the DN4 Questionnaire fall within an acceptable range for distinguishing neuropathic pain from non-neuropathic pain, based on the current literature. Similar to Mathieson et al.’s findings (11), we believe that while the DN4 Questionnaire is a valuable screening tool in clinical practice, it should be used alongside other diagnostic modalities to enhance diagnostic accuracy.

It is important to consider several factors that may limit the final interpretations and should be addressed in future studies. These include the limited availability of evidence on the DN4 Questionnaire in different languages due to small sample sizes, the use of imprecise and inconsistent methodologies across studies, and the failure of some studies to specify time intervals between initial testing and retesting. This omission could introduce recall bias, as the questionnaire relies on self-reporting and individual interpretation. Additionally, cultural and contextual differences across various countries may influence the results, further underscoring the need for standardized validation studies in diverse populations.

On the other hand, mixed pain (a combination of neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain) presents another challenge that requires attention. In clinical settings, pain is not strictly classified into neuropathic and non-neuropathic categories; rather, some patients experience mixed pain, which can impact the performance and diagnostic accuracy of screening tests.

Some of the exceptionally high diagnostic performance results observed for the DN4 screening questionnaire may be attributed to the exclusion of mixed pain cases in certain studies. For example, in the study by Sykioti et al. (30), when only definite neuropathic and non-neuropathic populations were analyzed, the AUC, sensitivity, and specificity were reported as 0.919, 92.7%, and 78%, respectively. However, when individuals with mixed pain (neuropathic, mixed, and non-neuropathic) were included in the analysis, these values decreased to 0.887, 88.8%, and 78%, respectively. This suggests that incorporating mixed pain cases in analyses leads to a decline in diagnostic accuracy.

Therefore, it is important to recognize that screening tests like DN4 may have limitations in real-world clinical settings, where pain classification is not always clear-cut. As a recommendation for future research, further studies on screening questionnaires, particularly the DN4, should be conducted in multiple languages with standardized methodologies and larger sample sizes. To ensure results are more reflective of real-world clinical practice, it is advisable to include patients with mixed pain in final analyses.

5.1. Conclusions

Our systematic review found that the DN4 neuropathic questionnaire demonstrates an acceptable range of measurement properties for identifying and differentiating neuropathic pain, primarily as a screening tool for further evaluation rather than a standalone diagnostic measure. However, its effectiveness may be limited by small sample sizes, potential recall bias, and its applicability in cases of mixed pain. In clinical settings where pain cannot be distinctly classified as neuropathic or non-neuropathic, the DN4 Questionnaire's diagnostic accuracy may be compromised.

Future research should include individuals with mixed pain in analyses to obtain results that better reflect real-world clinical scenarios. Additionally, further studies with larger sample sizes and standardized methodologies are necessary to improve the understanding of the DN4 Questionnaire’s performance across diverse populations and pain conditions.

In conclusion, while the DN4 Questionnaire is a valuable tool for identifying neuropathic pain when used alongside other diagnostic methods, further research is needed to address its limitations and enhance its clinical applicability.