1. Introduction

Coxiella Burnetii is a gram-negative intracellular pathogen that causes Q fever. Humans primarily acquire Q fever through inhalation of infected aerosols, usually originating from livestock or dairy products (1). Ticks can spread the bacteria from sick animals to susceptible hosts and contaminate the environment with their feces (2). The first report on Q fever in Iran was published in the 1970s (3). However, there have been limited reports of Q fever in Iran in recent years, possibly due to the insidious nature of the disease and the shortage of diagnostic tests in most laboratories. Two seroepidemiological studies on Q fever utilizing IgG testing in high-risk populations in Fars province, southern Iran, and Kurdistan province, western Iran, reported seropositivity rates of 26.7% and 27.8%, respectively (4, 5).

Longitudinal investigations have indicated a 1.3% - 2.3% incidence of neurological involvement in acute Q fever, commonly presenting as meningoencephalitis, followed by meningitis (6). The most common symptoms of central nervous system (CNS) involvement in Q fever are fever, headache, myalgia, lethargy, focal neurological deficits, seizures, and meningismus (6, 7). Although there are few reports of unusual presentations of Q fever in Iran (8, 9), no cases of C. burnetii meningitis have been recorded. This report details the first case of C. burnetii meningitis in a soldier, including his diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up history.

2. Case Presentation

Our patient was a 23-year-old soldier living in Chaharmahal-O-Bakhtiari province, west of Iran, who presented to Khanevadeh General Academic Hospital in Tehran with fever, headache, and myalgia, unresponsive to outpatient antimicrobial treatment for two weeks in May 2018. He confirmed a history of interaction with livestock three months prior to the start of military training. At the time of presentation, he was alert and had a fever of 38.5°C, a pulse rate of 84 beats/min, and a respiratory rate of 22 breaths/min. Physical examination revealed mild photophobia, meningismus, bilateral conjunctivitis, and sweating.

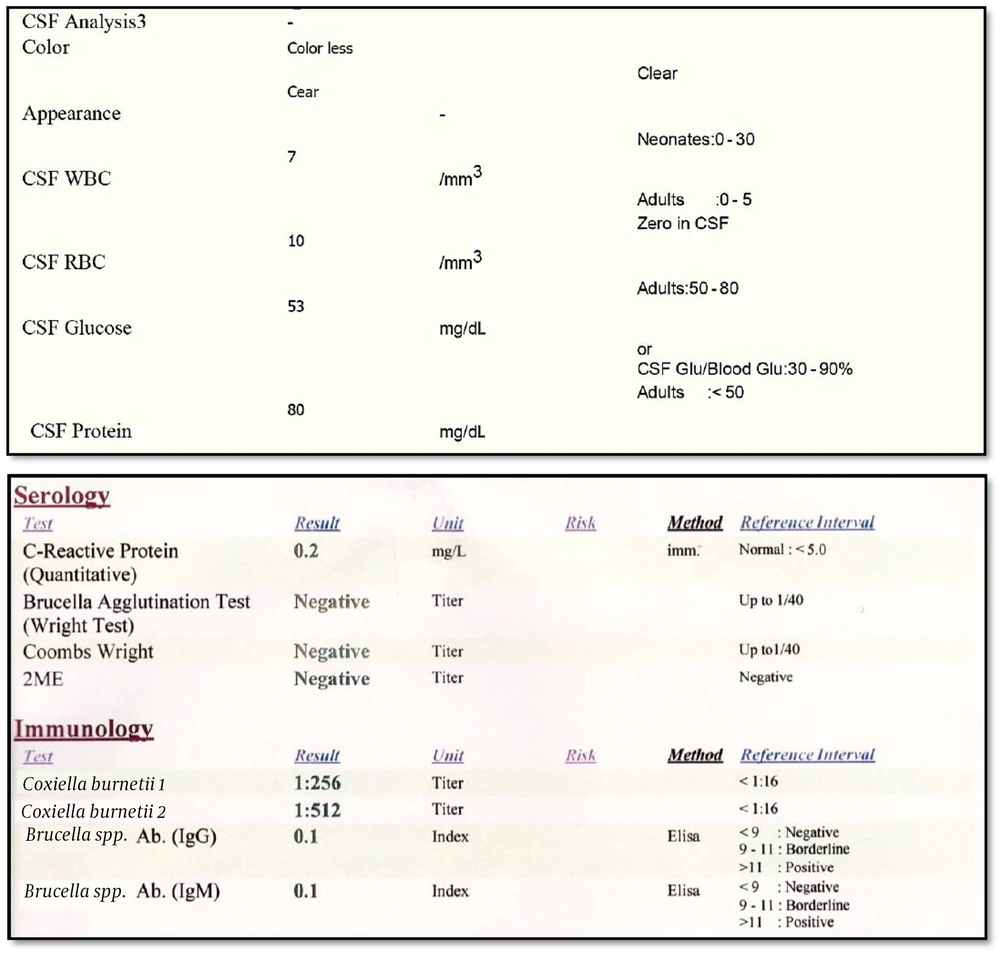

Initial laboratory findings were as follows: WBC = 6800 cells/mL, Hb = 15.2 mg/dL, Plt = 186,000 per mL, first-hour ESR = 14, CRP = Negative, AST = 40 IU/mL, ALT = 85 IU/mL, and normal electrolytes. After a normal brain computed tomography, the patient underwent a spinal tap. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a WBC of 7 cells/mL, a protein level of 80 mg/dL, and a glucose level of 53 mg/dL. Our primary diagnosis was meningoencephalitis of unknown etiology. Therefore, we initiated treatment with ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and acyclovir. However, he did not recover over the following days and developed lethargy, vomiting, and worsening headache.

The CSF gram-staining, culture, and multiplex polymerase chain reaction tests for tuberculosis, brucellosis, cryptococcosis, fungal infections, HSV, EBV, CMV, influenza, and adenovirus were all negative, as were serum agglutination (Wright), antiglobulin serum agglutination (Coombs Wright), and HIV antibody tests. Furthermore, echocardiography and abdominopelvic sonography results were normal. Consequently, we requested serum anti-C. burnetii antibody and PCR tests. The laboratory used the Complement Fixation test by VIDAS® 3, BioMérieux Corporation, France, and PCR test by LightCycler® 96 Instrument, Roche Corporation, Switzerland. The results showed a negative PCR but a positive antibody test with a titer of 1:256 for Type 1 and a titer of 1:512 for Type 2 using the complement fixation method (Figure 1).

Based on the epidemiological characteristics, clinical presentation, and antibody results, we diagnosed C. burnetii meningitis and started oral doxycycline at a dose of 100 mg twice daily, which led to dramatic improvement within a week. The patient was discharged with oral doxycycline for one year, resulting in complete recovery without neurological complications. We followed up with the patient for two years. He reported some degree of fatigue and dysthymia during the initial months after discharge. However, he gradually became symptom-free after completing the treatment.

3. Discussion

We presented a case of C. burnetii meningitis in a soldier during military training. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of Q fever meningitis in Iran. Fewer than 50 cases of C. burnetii meningitis have been reported in the literature. Most of these cases have been reported in young men in their third to fifth decades, similar to our patient, where the risk factor of contact with livestock is more common (10-12). Mild pleocytosis, in the range of 100 to 1000 cells/mL, has been observed in most instances of CNS Q fever, accompanied by a slight elevation in protein levels and mild hypoglycorrhachia (10, 11, 13).

The diagnosis of CNS infection of Q fever is based on clinical symptoms, CSF analysis, and antibody testing. PCR testing may not be feasible due to the chronic nature of the disease and the low bacterial density at the time of testing. Only one study has used the metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) technique on serum samples for the diagnosis of Q fever in a patient with aseptic meningitis (14). Our diagnosis was also made by antibody testing, along with clinical symptoms and CSF findings. The antibody titer of Type 2 is higher than Type 1 in acute C. burnetii infections, as seen in our patient, whereas in chronic infection, it is vice versa. Doxycycline is the treatment of choice in these patients and should be continued for one year (10, 12, 15).

Although our patient did not experience any complications, other studies have reported neurological complications, including sensorimotor neuropathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, cranial nerve palsy, stroke, optic neuritis, and even death (6, 16, 17). The management of CNS Q fever is challenging and requires thorough evaluation due to the potential severity of the condition. Patients require extended monitoring because of the potential for subsequent relapses.

The available data lacks specific information regarding the prognosis of CNS involvement in Q fever. However, CNS involvement in many types of infections, including C. burnetii, is frequently associated with increased severity of disease and adverse outcomes. The prognosis may differ based on the specific infection, degree of CNS involvement, and promptness of diagnosis and treatment. Nevertheless, timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment can potentially enhance outcomes in numerous instances.

3.1. Conclusions

Central nervous system involvement in Q fever can range from mild meningitis to severe encephalitis, accompanied by various neurological abnormalities. Healthcare practitioners need to maintain a heightened suspicion of Q fever in patients displaying neurological symptoms, especially in endemic areas or among those with potential exposure to the causative agent. We recommend providing access to PCR and antibody testing for C. burnetii and advocate for these tests in cases of unexplained meningitis or meningoencephalitis.

3.2. Limitations

The unavailability of the test kit for C. burnetii constitutes a limitation for patient follow-up after treatment completion. Consequently, we were unable to serologically monitor the changes in antibody titers 1 and 2.