1. Background

Helicobacter pylori are microaerophilic gram-negative bacteria that infect more than half of the world’s population. This pathogen has been categorized as a group I carcinogen by the international agency for research on cancer and its infection occurs more frequently in developing countries than in industrialized countries (1). Colonization in the human stomach commonly leads to gastritis that could progress to ulcer in the duodenum or the stomach. In some cases, the disease can finally cause mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas or gastric carcinoma in nearly 1% of the patients (2). Although infection with H. pylori is a global health problem, socioeconomic class, age, and health status affects its prevalence in different countries (3). In Iran, it was estimated that 80% of the adult population have a history of infection with these bacteria (4). However, recent studies revealed that this rate has decreased up to 40% in some cities with higher socioeconomic status (5).

Efforts to improve health status and administration of appropriate doses of antibiotic regimens for eradication therapy could be effective in the control of H. pylori infection in developing countries. The eradication can be achieved by using combination therapies consisting of a proton pump inhibitor or bismuth citrate and two antibiotics, such as amoxicillin (AML), clarithromycin (CLR) or metronidazole (MTZ). Failure of eradication therapy in these patients is mainly due to the resistance property of the responsible strains to the prescribed antibiotics (6). Eradication failure in these patients is commonly associated with recurrence of the infection by those strains that are resistant to the prescribed drugs. Since resistance to antibiotics is the main reason for treatment failure, knowledge about minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of the prescribing antibiotics for bacterial strains could help clinicians select the best choice of medication in each geographic region (7).

Metronidazole is one of the main drugs commonly prescribed for this infection worldwide. Resistance of H. pylori to metronidazole is a growing medical problem in Iran and various parts of the world. Previous studies illustrated that metronidazole resistance is very high in Africa (80% - 100%) and Asia (50% - 95%) (8). Different rates of resistance to metronidazole were reported in the United States, ranging from about 20% to more than 50%. Similarly, the collected data showed an increasing trend of resistance to metronidazole in the recent years in Iran (94%) (9). Eradication rate of triple therapy regimens was found as 97% in metronidazole-susceptible strains, which was much higher than the value for the metronidazole-resistant strains (72.6%) (10). According to the latest guideline for H. pylori medication, the prescribed regimens should be selected based on resistance of H. pylori strains to metronidazole and clarithromycin in each geographic region (11). Therefore, constant monitoring of infection rate and resistance property of the responsible strains is necessary to choose the best treatment option for eradication of resistant cases in each country. While there are some data about this resistance in different cities of Iran, lack of data exists for their MIC levels at a broad range of antibiotic concentrations. In this study, we provided these data to help physicians with better management of H. pylori infection in Iran.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the susceptibility of H. pylori strains and their MIC values among infected patients with different gastric disorders in Tehran, Iran.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Patients and Bacterial Strains

In this cross-sectional study, H. pylori infection was investigated among 96 dyspeptic patients, who had referred to the Endoscopy Unit of a governmental hospital (Imam Khomeini hospital) in Tehran, Iran, during year 2013. Simple random sampling was used for the patients and data were collected using a standardized questionnaire. All the patients signed an informed consent form. Exclusion criteria for the study included usage of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors within the last two weeks prior to the endoscopy, and bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy was requested and biopsy sampling was performed for the patients, based on the standards of practice committee of the American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy (12, 13). The biopsies were transported to the laboratory in a sterile tube containing semi solid Thioglycollate medium (Merck, Homburg, Germany) supplemented with 3% yeast extract (Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, UK) for culture in a selective medium as described below. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (SBMU 721).

3.2. Isolation and Identification of Helicobacter pylori

The biopsy samples were gently homogenized and cultured on Brucella agar medium (Merck, Homburg, Germany) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood, 7% fetal bovine serum (FCS), amphotericin B (10 mg, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and Campylobacter selective supplement consisting of vancomycin 2.0 mg, polymyxin 0.05 mg and trimethoprim 1.0 mg (Merck, Homburg, Germany), as a selective medium for H. pylori strains. The inoculated plates were incubated at 37°C under microaerobic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, and 85% N2) in a CO2 incubator (Innova-Co 170; USA). The cultures were examined after three to seven days for observation of pinpoint (1 - 2 mm) glistening colonies. The bacterial strains were identified as H. pylori on the basis of data regarding their spiral microscopic appearance, as well as positive activities of urease, oxidase, catalase tests and polymerase chain reaction results that were obtained using species specific primers (Section 3.2; 10). Individual cultures representing colonies from each patient was frozen at -70°C in brain heart infusion broth (Merck Co, Germany) containing 15% glycerol (Merck Co, Germany) and FCS (20%) for further studies.

3.3. DNA Extraction and Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification Analysis

To confirm identity of the bacterial isolates, DNA extraction was performed on freshly grown colonies of the isolates using QIAamp tissue DNA extraction kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The PCR was done by primers targeting glmM (ureC), which amplify a 296-bp fragment. The PCR was performed in a final volume of 25 μL containing 2.5 µL PCR buffer (10 X), 0.3 µL of each primer, forward primer: GlmM2-F 5ʹ-GGATAAGCTTTTAGGGGTGTTAGGGG and reverse primer: GlmM1-R 5ʹ-GCTTACTTTCTAACACTAACGCGC, 1 mM MgCl2; 0.3 µL each deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate (dNTP), 0.2 µL Taq DNA polymerase, and 3 µL DNA sample. It was implemented in a thermocycler (AG 22331; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) under the following conditions: initial denaturation for four minutes at 94°C followed by 30 cycles at 94°C for one minute, 57°C for 45 seconds and 72°C for one minute. After a final extension at 72°C for ten minutes, electrophoresis was done on 1.2% agarose gel, according to standard procedures. DNA of the H. pylori strain RIGLD 245 (GenBank accession number JQ765441.1) was used as an internal control for the PCR assay.

3.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Susceptibility of the bacterial strains was determined based on guidelines of the European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing (EUCAST) (14). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using the agar dilution method. Accordingly, a stock solution of metronidazole (MAST, London, United Kingdom) was prepared in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and the working solutions were made in distilled water at appropriate concentrations immediately before incorporation into sterile Muller Hinton agar medium (MHA, 45°C) in ranges of 8 to 512 μg/mL at two-fold dilutions (6). To inoculate the plates, an inoculum of freshly prepared H. pylori suspension was adjusted to a density corresponding to 2 McFarland’s turbidity standard tube in normal saline and then 5 µL of bacterial suspension was inoculated on Muller-Hinton agar (Merck, Germany). The inoculated plates were left at room temperature for 10 minutes for drying and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 - 72 hours. The EUCAST clinical breakpoint of > 8 µg/mL was defined for evaluation of the resistant strains and MIC values were recorded in each case (14). Helicobacter pylori strain RIGLD 245 was used as a reference strain for all the experiments.

3.5. Data Analysis

Fisher’s exact test was used for analysis of the categorical data. Bootstrap confidence interval was measured using the StatKey software. Analyses were done using statistical analysis for windows V2.03 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). P values of less than 0.05 were considered statically significant.

4. Results

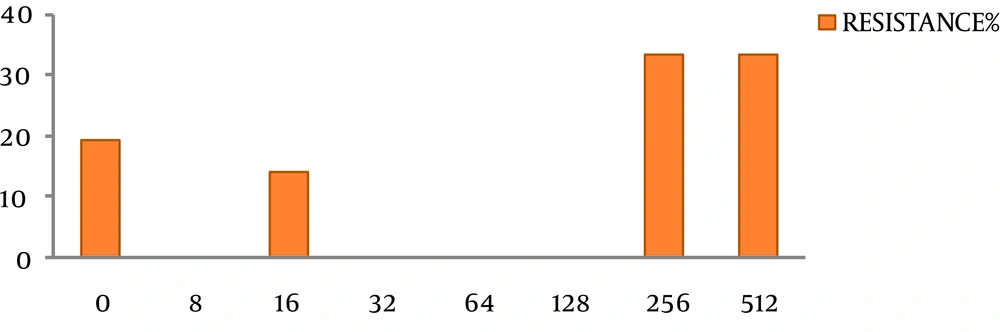

Out of the 96 studied patients, consisting of 52 males (54.1%) and 44 females (45.8%), H. pylori infection were detected in 22 patients (22.92%). The isolates indicated positive results for the common identification tests and H. pylori-specific PCR (glmM). The ages of the patients ranged between 15 and 88 years. Most of the infected patients suffered from chronic gastritis (70.1%), while the others showed duodenitis (6.25%), intestinal metaplasia (1.04%), dysplasia (1.4%) and cancer (10.41%). In this study, smoking was negatively related to H. pylori infection. In other words, non-smokers had a 2.9-fold higher risk of H. pylori infection than smokers. The rate of antibiotic resistance in the current study was 81.8% (18/22). Minimum inhibitory concentration ranges of 8 to 512 μg/mL were detected for the 22 H. pylori strains against metronidazole (Figure 1). On the basis of our findings, resistance to metronidazole was equal in the female and male patients. An MIC of ≥ 512 μg/mL was detected among 40.9% of the metronidazole-resistant strains. Furthermore, MIC50 and MIC90 of all the isolates were determined as 256 and 512 µg/mL, respectively (Table 1). In our study, no significant correlation was found between resistance to metronidazole and gender or owning a pet (P > 0.05, CI, 0.003) (Table 2).

| Gender | MTZ Resistance No. (%) | MIC ≤ 8 | MIC = 16 - 128 | MIC = 256 | MIC = 512 | MIC50/MIC90 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males, n = 12 | 9 (40.90) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Females, n = 10 | 9 (40.90) | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total, n = 22 | 18 (81.80) | 4 (18.1) | 3 (13.6) | 7 (31.8) | 8 (36.3) | 256/512 |

Abbreviations: MTZ, metronidazole; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration ((µg/mL); MIC50, the MIC value at which 50% of the tested strains were inhibited; MIC90, the MIC value at which 90% of the tested strains were inhibited.

| Variable | Frequency, No. (%) | Positive Culture, No. (%) | Negative Culture, No. (%) | Resistance to Metronidazole, MIC, µg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 44 (45.8) | 10 (10.41) | 34 (35.41) | ≤ 8 - ≥ 512 |

| Male | 52 (54.1) | 12 (12.5) | 40 (41.66) | ≤ 8 - ≥ 512 |

| Atrophy | 7 (7.2) | 1 (1.04) | 6 (6.25) | 256 |

| Chronic gastritis | 46 (47.91) | 12 (12.5) | 34 (35.41) | ≥ 512 |

| Severe active gastritis | 2 (2.08) | NA | 2 (2.08) | NA |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 2 (2.08) | NA | 2 (2.08) | NA |

| Antibiotic usage | 9 (9.37) | 0 | 9 (9.37) | NA |

| PPI usage | 7 (7.29) | 2 (2.08) | 5 (5.2) | ≤ 8 - ≥ 256 |

| Cancer | 9 (9.37) | 2 (2.08) | 7 (7.2) | 256 - ≥ 512 |

| Peptic ulcer | 28 (29.16) | 4 (4.1) | 24 (25) | 256 - ≥ 512 |

| Moderate gastritis | 1 (1.04) | NA | 1 (1.04) | 256 - ≥ 512 |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

5. Discussion

H. pylori are the main pathogens for gastroduodenal diseases. It is now well-known that late stages of H. pylori infection may cause gastric atrophy with intestinal metaplasia, and that this injury probably predispose an individual to gastric cancer. Metronidazole is the main antibiotic used in numerous eradication therapy regimens for treatment of H. pylori infection; however increasing resistance to this antibiotic is a worldwide problem. It appears that the main resistance to metronidazole has been attributed to frequent use of this drug, which is regularly prescribed for other diseases and infections. For this reason, metronidazole has been omitted from first-line experiential therapy strategies in some countries (15). Prolonged amoxicillin-based standard triple therapy was recommended by the European guidelines for countries with > 40% metronidazole resistant H. pylori strains (16). In the present study, a high rate of resistance to metronidazole was characterized among the Iranian H. pylori strains, which is higher than those reported previously from Iran. There are variable resistance rates in different countries. While a higher resistance rate was reported in India (85%), a lower rate was determined in the USA (33.9%) during years 2000 to 2012 (8, 10). These differences were also seen among different cities of Iran. In the north of Iran, resistance to metronidazole was reported as 73.4% during 2007 to 2010 (17); however the rate of resistance in south of Iran (Shiraz) decreased from 72.6% in 2007 to 44% in 2010 (14, 18). Mirzaei et al. (19) reported a resistance rate of 56.3% to metronidazole in Isfahan in June 2013, yet the resistance rate was higher in Tehran, Iran (78% and 61.3%) (6). Comparison of data from different studies is difficult, as in many instances a different methodology has been used (20-22). Further studies are needed to confirm these results in a higher sample collection from different provinces of Iran. Since practical treatment is ordinarily used in clinical therapies without any care about resistance rate of H. pylori strains in Iran, there is an increasing risk of drug resistance. Results of our study confirmed increased levels of resistance rate and MIC50 and MIC90 values among these strains that was higher than those reported previously in Tehran during year 2011 (16 and > 32 µg/mL, respectively) (23). Therefore, monitoring of antibiotic resistance seems to be essential to present appropriate treatment regimens. Prescription of treatment regimens based on the susceptibility tests will reduce chronic infection that consequently could limit emergence of new resistant variants of H. pylori in the infected patients. Although this will make management more expensive, it will be cost effective since it will provide better eradication of the organism.

In conclusion, these results showed an increased rate of resistance to metronidazole and MIC values among the H. pylori strains in Tehran, which proposed a switch to second line therapy for treatment of this infection by physicians in Iran. Better management of the infection depends on detection of H. pylori eradication rates based on the prescribed regimens and performance of antimicrobial susceptibility tests.