1. Context

Around 55.9% of the world’s population is employed (1). The relationship between work and family life follows a two-way street. This means that not only does work affects family matters, but family affairs can also spread to the workplace (2). The risk of work-life imbalances has been extensively studied in recent decades (3), leading to the emergence of concepts such as work-family conflicts, family-work conflicts, and work-life balance. When work-related issues spread to the family domain (i.e., work-family conflicts), or when family issues spread to the workplace (i.e., family-work conflicts), the balance of life-work is deranged (2). The term work-life balance refers to the relationship between work and non-work aspects of people’s lives and is defined as the compatibility between work and family roles and the simultaneous fulfillment of both of these roles (4). The work-life balance determines how much time the employed person has in order to balance the demands of the family and work (3).

Work-family conflicts have been identified as a predictor of employee misconduct, absenteeism (2), and burnout (5). It can also lead to various problems, such as depression, anxiety, mood disorders, and marital disorders for both men and women (6, 7). In addition, reduced job satisfaction (7, 8) and reduced quality of parental role are among other negative consequences of work-life imbalance (9).

The issue of work-life conflict soared increasingly, especially after World War II, when there was an increasing number of women entering the labor market to compensate for the lack of male labor. Since then, women, like men, have greatly participated in the economic and social development of societies (10). Working women, in addition to their job responsibilities, are also responsible for most household chores, child care, and caring for the family’s elderly members (11). According to a study by Zayed et al., 82.4% of working women were responsible for all household chores (12). This is while 25% of women were not able to fulfill their family responsibilities due to job responsibilities (13). Efforts to balance the competing demands of work and family have become a stressful dilemma in the daily lives of working women, and the issue of work-life balance for women has acquired great attention (14).

The social expectations and behavioral norms that women face when playing a combination of family and work roles have led working women to experience higher levels of work-family conflicts and job-family stress than their male counterparts (6, 15). Also, increasing job demands and higher job ranks exaggerate caricatured family conflicts for women. Working mothers commonly face poor mental health, long-term headaches, high blood pressure, stabbing, and even guilt as the consequences of work-life imbalance (14).

If working women can reduce work-life conflicts and create the right balance between their work and other life roles, they will achieve a healthier, happier, and more successful life (16) and experience greater life satisfaction (13). A proper work-life balance also increases job satisfaction (8), organizational commitment, and productivity among employees (17). However, 78% of working women are not able to create a proper work-life balance (6). Thus, the issue of how to balance work and life has attracted much attention at the national and international levels, and public effort to find policies that promote work-life balance in women continues (3).

2. Objectives

Various factors related to work-family conflicts in women have been reported in different studies. These factors are dispersed and diverse, and there is no comprehensive information and effective interventions at the individual, organizational, and national levels to reduce work-family conflicts. To the best of our knowledge, there are no reviews focusing on the identification and classification of the factors related to work-family conflicts. Thus, this systematic review aims to identify the personal, interpersonal, organizational, and cultural factors associated with work-family conflicts among women.

3. Methods

This research was conducted as a systematic review from June 2000 until June 2021. The search was performed using English keywords and appropriate search strategies and correlation letters in the electronic databases of Science Direct, Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, and Scopus (Table 1). The Google scholar search engine was also searched to ensure access to relevant studies. In addition, a source search for gray literature was conducted in print journals and abstracts of conference papers. The citations obtained were entered into EndNote 20 software and examined.

| References | Database | Search Strategy | Initial Search |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | Database | ((“Factors” [tiab] OR “affecting” [tiab]* OR “affecting factor” [tiab] OR “influential factors” [tiab] OR “risk factor” [tiab] OR “risk factors” [tiab] OR “related factor” [tiab] OR “related factors” [tiab] OR “Related Factors” [tiab] OR “Associated Factor” [tiab] OR “Associated Factors” [tiab] ) AND (“Female” [Mesh] OR “Women” [Mesh] OR “women, working" [Mesh] OR ”women employees" [tiab] OR “Employee women” [tiab]) | 910 |

| AND ("work-life balance"[Mesh] OR "life-work imbalance" [tiab] OR "life conflict job" [tiab] OR "life conflict occupational"[tiab] OR "work-life challenges" [tiab] OR "work-family conflict"[tiab] OR "Work-to-family conflict" [tiab] OR “Family-to-work conflict” [tiab])) | |||

| Scopus | Database | TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( ( "Factors" OR (("affecting" OR "influential factors" OR "risk factors" OR "related factor" OR "related factors" OR "Associated Factor" OR "Associated Factors" ) AND ( "Female" OR "Women" OR "women, working" OR "women employees" OR "Employee women" ) AND ( "work-life balance" OR "life-work imbalance" OR "life conflict job" OR "life conflict occupational" OR "work-life challenges" OR "work-family conflict" OR "Work-to-family conflict" OR "Family-to-work conflict" ) ) ) | 1387 |

| Web of Science | Database | (TI = ("work-life balance" OR "life-work imbalance" OR "life conflict job" OR "life conflict occupational" OR "work-life challenges" OR "work-family conflict" OR "Work-to-family conflict" OR "Family-to-work conflict") AND TI = ("Female" OR "Women" OR "women, working" OR "women employees" OR "Employee women")) AND LANGUAGE: (English) | 162 |

| Timespan: 2000-2021. Indexes: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, ESCI. | |||

| Science Direct | Database | "((influential factors" OR "related factors" OR "Associated Factors") AND women OR "women, working" OR "Employee women") AND ("life _ work balance" OR "life-work imbalance" OR "work-family conflict")) | 211 |

| Embase | Database | ((affecting:ti,ab,kw OR 'influential factors':ti,ab,kw OR 'risk factor':ti,ab,kw OR 'associated factor':ti,ab,kw) AND female:ti,ab,kw OR women:ti,ab,kw OR 'women, working':ti,ab,kw OR 'women employees':ti,ab,kw OR 'employeewomen':ti,ab,kw) AND 'life conflict job':ti,ab,kw OR 'life conflict occupational':ti,ab,kw OR 'work-life challenges':ti,ab,kw OR 'work-family conflict':ti,ab,kw OR 'work-to-family conflict':ti,ab,kw OR 'family-to-work conflict':ti,ab,kw)) | 738 |

| Google Scholar | Search Engine | (("work-life balance" OR""life-work imbalance" OR "life conflict job" OR "life conflict occupational" OR "work-life challenges" OR "work-family conflict" OR "Work-to-family conflict" OR "Family-to-work conflict" ) AND ( "Female" OR "Women" )) | 158 |

| Unfild | 410 | ||

| 3967 |

a The [tiab] field code was used after each free-text term to restrict the query to search in the title and abstract of each article.

All cross-sectional studies conducted on the factors related to work-life conflicts among working women from June 2000 to June 2021 were included. Only studies were included that had been published in English, worked only on female populations (or examined females separately from males), and studied work-life conflicts or work-life balance as the outcome variable. The search strategy (keywords and databases) was limited to the English language. Duplicates were detected using EndNote’s duplicate identification tool and then removed manually.

Studies on non-women or reporting the results of both sexes together, articles published outside the time frame mentioned, reviews, books, those lacking full-text, and studies that did not address the factors related to conflicts between work and life among working women were omitted. We also searched documents that cited any of the initially included studies, as well as the references of the primarily included studies. However, no additional articles that could meet the inclusion criteria were found in these sources. Careful studying of these articles revealed important points about the conflict between work and life that solved an important part of the balance puzzle. A consensus was reached with the participation of a third party and discussion.

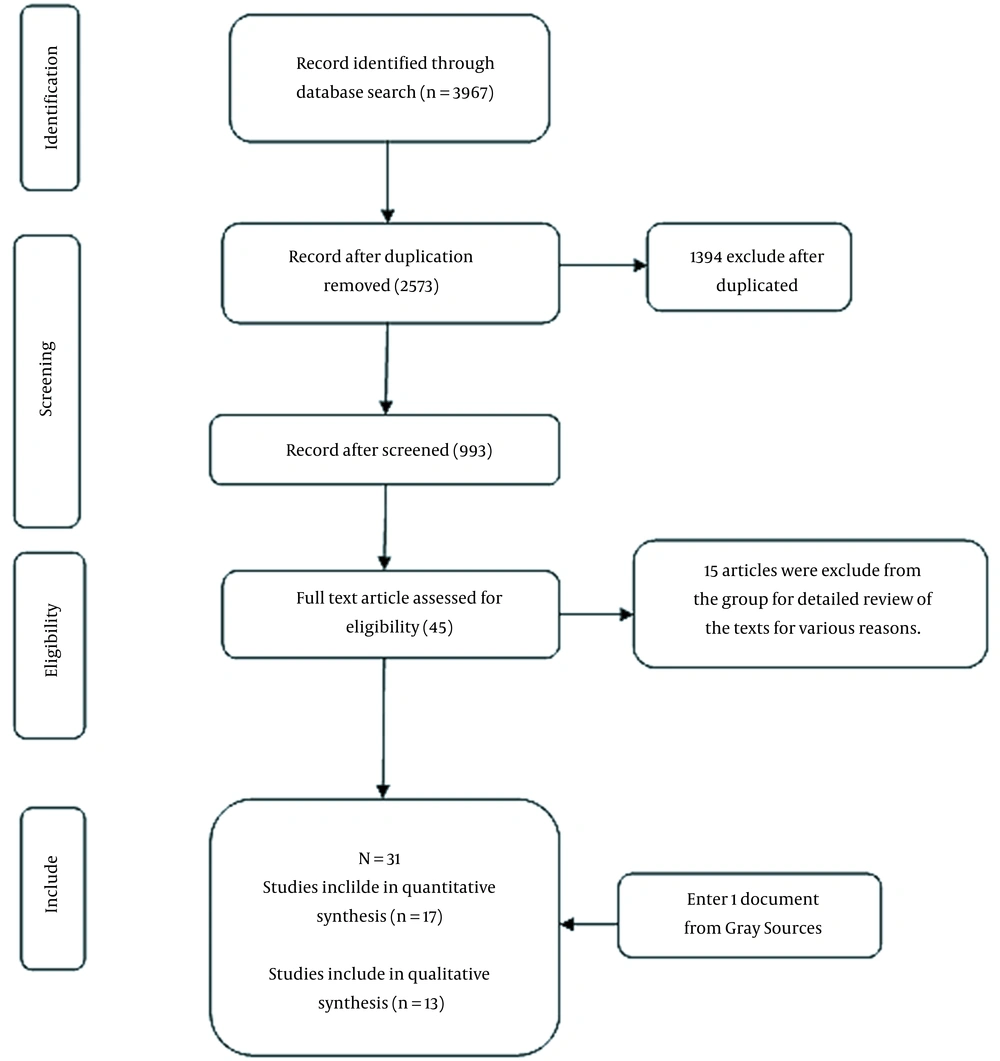

In total, 3967 articles were identified, of which 1394 duplicate articles were excluded, and 2573 articles remained for reviewing titles and abstracts, resulting in the exclusion of 1046 additional items. In the first stage, the titles of the articles were reviewed, then the abstracts of 993 remaining articles were studied in the next step, of which 45 items were finally selected for reading the full text. Of these, 14 were removed due to the unavailability of the full text or being a part of a book. Of the remaining 31 articles, 13 were qualitative studies, and 17 were quantitative studies. One article was added to the final articles after reviewing grey literature (Figure 1).

Data extraction from quantitative studies was conducted based on significant differences observed in the work-family conflict between subgroups of women or a significant relationship (e.g., correlation) between work-family conflict scores and the factors studied by the researchers (the significance level of 0.5). In qualitative studies, the factors identified in interviews and the themes extracted were used to record data. Two reviewers independently collected data from each article, and a third reviewer checked their reports for accuracy and resolved disagreements. Finally, the findings were provided to a fourth researcher who reviewed the articles to find possible factors that may not have been extracted in the previous steps.

Table 2 summarizes the articles that were finally analyzed (Table 2). Some studies did not specify the location of the study, so we used the year of publication.

| Code | Author(s)/Country/Year | Type of Study | Type of Analysis/Data Collection Method | Sample Size/Age | Important Determinants of Work-Life Conflicts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Human Resource Management International Digest/United Kingdom/2021 (18) | Qualitative | Thematic analysis/interview | 15 women | Individual: personality types, stage of working life; Organizational: Organizational policies and commitments |

| 2 | Ademuyiwa et al./Nigeria/2021 (19) | Quantitative | Average response ranking/Hierarchical sampling/questionnaire | 896 questionnaires | Individual: Stress, mental fatigue, burnout; Interpersonal: Lack of helpers at home; Organizational: Lack of support from colleagues in performing official duties |

| 3 | Adisa et al./Nigeria/2019 (20) | Qualitative | Thematic analysis/semi-structured interview | 32 women | Cultural factors: cultural contexts [patriarchy in society] |

| 4 | Akkas et al./Bangladesh/2015 (21) | Qualitative and quantitative | Targeted sampling method | 50 women | Individual: life role values, perfectionism, number of children, life cycle stage; Interpersonal: Family involvement, child care arrangements; Organization: Long working hours, organizational inflexibility, overtime work, discrimination in the workplace, and authoritarian management styles |

| 5 | Bernas and Major/United Kingdom/2000 (22) | Quantitative | Path analysis tests finding relationships | 206 questionnaires | Organizational: Having a quality relationship with the supervisor can reduce work-life conflicts and associated stress |

| 6 | Bharathi and Mala/India/2016 (23) | Quantitative | Analysis of exploratory factors | 186 employed women | Individual: Personal perception of people such as lack of time to do things, not paying enough attention to themselves, feeling guilty for not caring enough for children |

| 7 | Brown et al./United States and the Republic of Korea/2020 (24) | Qualitative | Thematic analysis | 20 working women in America, 20 working women in Korea | Cultural factors: A Strong Organizational culture in America; Strong social culture; [like family-friendly culture and social support in Korea] |

| 8 | Choi/Korea/2020 (25) | Quantitative | Multiple regression scanning and analysis | 226 women | Organizational: There is a strong positive relationship between perceived organizational support and work-family conflicts among female employees |

| 9 | Eckart and Ziomek‐Daigle/United States/2019 (26) | Quantitative | Multiple correlations and regressions | 226 women | Individual: Number of children under 18 years at home, caring for the elderly or sick with special needs; Organizational: Working hours per week, work experience, flexibility in the workplace, autonomy in the workplace |

| 10 | Wei et al./China/2009 (27) | Qualitative | Content analysis | 121 women | Individual: The role of self-perceived professional and social factors by the individual, education, income, and work experience; Interpersonal: Spouse’s stress and sacrificing the family's satisfaction |

| 11 | Hassan/Malaysia/2020 (28) | Qualitative | Content analysis | 76 women | Organizational: Incentives and services provided by employers and institutions to reduce the workload of women [adequate leave, flexibility in management and working hours, and support system] |

| 12 | Hassan et al./Malaysia/2020 (29) | Quantitative | Correlation | 80 women | Organizational: There was a relationship between workplace spirituality [meaningful work and a sense of consensus] and work-life balance. |

| 13 | Kang and Wang/Korea/2018 (4) | Qualitative | 6-step cresol analysis | 16 women | Individual: Concerns about child care, a strong craving for a job, and career aspirations; Interpersonal: Lack of support from family and colleagues; Organizational: Lack of support systems |

| 14 | Kaur et al./India/2018 (30) | Quantitative | Correlation | 100 working women | Individual: Life concerns like babysitting; Organizational: Organizational inflexibility toward working women |

| 15 | Lee et al./United states/2013 (31) | Quantitative | Structural modeling technique | 276 married working women | Individual: Job satisfaction; Interpersonal: Receiving support from individuals, especially spouses |

| 16 | Lee et al./United States/2017 (32) | Quantitative | Hidden personality profile approach | 440 women | Individual: Personality traits [worker-oriented, parent-oriented, balanced] |

| 17 | Lo/Hong Kong/2003 (33) | Qualitative | Qualitative content analysis | 50 women | Interpersonal: The traditional culture of families and the many home responsibilities of women; Organizational: Inflexible policies of organizations |

| 18 | Maragatham and Amudha/India/2016 (34) | Quantitative | ANOVA and chi-square | 150 women | Individual: Mental balance and physical health; Interpersonal: Number of dependents and sponsors |

| 19 | Noor/Malaysia/2002 (35) | Quantitative | Regression analysis | 310 women | Interpersonal: Spouse support; Organizational: Long working hours and overloaded roles increase work-life conflict. |

| 20 | Nwagbara/Nigeria/2020 (36) | Qualitative | Exploratory | 43 women | Cultural factors: Cultural factors and social realities such as patriarchy in societies increase the intensity of work-life conflicts for women. |

| 21 | Rehman and Azam Roomi/Pakistan/2012 (37) | Qualitative | Interpretive phenomenology | 20 women | Individual: Lack of time planning; Interpersonal: Men do not accept women's responsibilities in the family; Cultural: Gender bias, social and cultural norms in a patriarchal society |

| 22 | Sane and Pingali/India/2015 (38) | Qualitative | Factor Analysis | Cultural: High household responsibilities due to the cultural context; Interpersonal: Lack of companionship between spouses | |

| 23 | Sudhindra et al./India/2020 (39) | Quantitative | Regression | 467 women | Interpersonal: Family support, caring for other people at home; Organizational: Organizational support in the workplace |

| 24 | Sundaresan/India/2014 (40) | Quantitative | Factor Analysis | 125 women | Individual: Having very little time for oneself, high levels of stress, and incoherence in household chores; Interpersonal: Expectations of others to meet their needs; Organizational: Excessive work pressure |

| 25 | Taghizadeh et al./Iran/2021 (6) | Qualitative | Factor analysis | 29 women | Individual: Job stress, insufficient individual abilities, and skills, high value for work and family; Interpersonal: unsupportive family environment, family overload, and hegemonic masculinity |

| 26 | Uddin et al./Bangladesh/2020 (41) | Quantitative | Path coefficient evaluation | 558 people | Organizational: Support and protectionist organizational policies |

| 27 | Uysal Irak et al./2019 (9) | Quantitative | Path analysis | 201 working mothers | Interpersonal: Spouses’ support; Organizational: Emotional support by the supervisor |

| 28 | Uzoigwe et al./Nigeria/2016 (42) | Quantitative | Multiple linear regression analysis | 173 women | Individual: Excessive family responsibilities and roles; Organizational: High job demands |

| 29 | Valk and Srinivasan/India/2011 (43) | Qualitative | Exploratory analysis | 13 women | Individual: Multipurpose responsibilities and try to solve them all; Interpersonal: Social support; Organizational: Supportive organizational policies and practices |

| 30 | Zayed et al./Egypt/2021 (12) | Quantitative | Correlation | 442 Women | Individual: Work overflows; Interpersonal and organizational: Lack of decision-making authority, lack of support from colleagues, and lack of support from supervisors |

| 31 | Zito et al./Italia/2013 (44) | Quantitative | Correlation | 207 nurses (92.5% female) | Organizational: Work shifts, overworking, lack of support of organizations to access more services such as child care centers; Individual: The cognitive burden of the conflict and how the individual perceives the issue |

3.1. Evaluation of the Quality of Articles

A 22-item checklist (strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) (STROB) was used to assess the quality of quantitative articles. Articles were classified into three categories: Good (scores in the range of 17 - 22), fair (scores of 16 - 18), and poor (scores of 1-7) based on the points earned in each item (Appendix 1).

The quality assessment tool developed by Hawker et al. was used for the quality assessment of qualitative studies. The tool includes nine items that are rated based on a four-point Likert scale (45). Each item’s score ranged from one (very poor) to four (good). The total score was between 9 and 36, and each article’s quality was determined based on the following classification: Class A (high-quality article with scores ranging from 30 to 36), class B (medium-quality articles with scores ranging from 24 to 29), and class C (low-quality articles with scores ranging from 9 to 24) (45). Two articles fell into class A, and eleven articles were placed in class B (Appendix 2).

Qualification of the articles was conducted independently by two researchers. In the case of disagreement, the article was reviewed by the third and fourth researchers.

3.2. Results of Quality Assessment

In total, 31 studies, including 13 qualitative studies and 17 quantitative studies, and a mixed-method study, were identified. Quantitative evaluation of the quantitative articles showed that they had acceptable quality. According to the STROB guide, four articles were placed in the good-quality category; 14 articles had fair qualities, and no articles had poor quality.

4. Results

An interesting point that seemed to be very important was the impact of cultural dimensions on work-life conflicts, such as the patriarchal cultural style or patriarchal hegemony. A total of 19 articles (61.3%) had been conducted in Asia (India 7, Malaysia 3, Korea 2, Pakistan 1, Iraq 1, Iran 1, Bangladesh 2, Pakistan 1, China 1, and Hong Kong 1), five articles (16.1%) in Africa (Nigeria 4 and Egypt 1), three articles (9.7%) in the United States, and three articles (3.7%) in Europe (Britain 2 and Italy 1). Also, a paper was jointly conducted in the United States and South Korea. In Europe, factors related to work-life conflicts were mostly classified into organizational and individual categories. A great variety of individual, interpersonal, and organizational factors were identified in Asian studies. Cultural and interpersonal factors were reported more in studies conducted in Africa. In American studies, factors were mostly placed under organizational, interpersonal, and individual categories; however, in general, they were not comparable in terms of variety and quantity to the studies conducted in Asia (see Table 2).

The related factors extracted from these articles at different levels have been presented in Table 2, summarizing the documents that have been finalized. Some studies did not specify the location of the study, so the authors used the year of publication.

4.1. Factors Related to Work-life Conflicts in Working Women

The results of this study identified four groups of factors related to work-life conflicts in women. These four groups include individual factors, interpersonal factors, organizational factors, and cultural factors.

4.1.1. Individual Factors

4.1.1.1. Individual Capacities and Skills

Time management is the most important skill that women need to create a work-life balance and prevent work-life conflicts (4, 6, 19, 21, 23, 37, 43). Short-term and long-term planning helps women to find the right time for each of their job and family roles (43). Proper knowledge of their own abilities can help women to allocate appropriate time for their work and home tasks (6, 19, 43). Higher individual skills and a better ability to manage available resources to handle various work and family responsibilities play an important role in achieving work-life balance (12). In addition, physical and mental capacities are higher than the factors associated with fewer work-life conflicts (4, 18, 22, 23, 28, 32-34). Physical health (34), an optimal emotional state, positive attitudes, hope for a better future, higher education, and mental health mitigate women's work-life conflicts (4, 22, 23, 28, 32-34). Among psychological factors, stress profoundly affects women’s creativity and initiative to better manage their work and life aspects (38). Job-related guilt, which means feeling guilty about working and therefore not being able to spend enough time with the family, is another psychological factor that exaggerates work-life conflicts in working women (9, 33).

4.1.1.2. Family Circumstances (Having a Small Child or Someone Needing Home Care)

Since women play a major role in childcare and caring for the elderly and dependents in need (38), they may face many challenges balancing their caregiver role (39). According to research, caring for children (19, 21, 23, 26, 30, 32, 33, 39, 43) and caring for elderly family members (23, 26, 33, 39, 43) and relatives (21, 39, 43) create significant work-life conflicts for working women.

4.1.1.3. Understanding and Knowing How to Reach Balance

Women who have a good understanding of the competition between home and job roles without denying or escaping the conflicts between these two try to prioritize their duties by developing their perspectives (37), believing that this is the first step to reducing and resolving the conflict (29). The work-life relationship for women can be divided into three aspects: family-oriented, work-oriented, and balance-oriented. Women who try to prioritize the balance between the family and work are less likely to encounter serious conflicts (4). For many women, choosing the family as the first priority is a good way to balance their work-life roles (4). Therefore, high commitment to the family helps to create job satisfaction and face fewer conflicts in work-life (27, 31, 43). One strategy used among Korean women was to create an image of a working mother avoiding overwork or unessential events at work (4). Also, women who believe in external control experience more work-life conflicts than those who believe in internal control (21).

4.1.1.4. Job Craving or Job Addiction

The desire for career advancement for women means spending more hours at work (4, 40). This makes married women less likely to do household chores such as childcare (32, 43). Job cravings even affect choosing partners among single women (43). On the other hand, women who appropriately control job cravings experience fewer work-life conflicts (6).

4.1.1.5. Perfectionism and Self-proof

For many women, being employed is more than just having an income. Jobs can be a factor in personal growth, self-exploration, and identity building. Having a job allows women to achieve independence in their actions and thoughts and to improve their worldviews (43). However, for most women, employment is a barrier to developing non-job skills, sports, and leisure activities, which can increase work-life conflicts (6, 21, 37, 39, 43).

4.1.2. Interpersonal Factors

4.1.2.1. Spouse Support

Spouse support, which includes emotional and instrumental support, has a unique role in preventing work-life conflicts from happening to women (4, 9, 19-21, 27, 31, 35). Emotional support includes behaviors and attitudes that encourage understanding and paying attention to the spouse and his/her problems, and instrumental support encompasses activities and recommendations that aim to help with the family’s daily affairs (9). Women who have good marital relationships with their husbands (21, 31) and are supported by them experience fewer work-life conflicts (21, 27, 31, 33, 35).

4.1.2.2. Support from Others

Support from others shows how other family members [excluding the spouse] and friends are committed to helping each other, including helping with household chores, caring for dependents, and doing other chores (41). Family members’ assisting working women in fulfilling their home and childcare roles can minimize workload pressure on the working mother (19, 22, 23, 39, 42).

4.1.2.3. Lack of a Partner in the Family

In most societies, the main responsibility of housekeeping is assigned to women, even if they are employed. For most women who do not have a job, being employed means that they have less time to do housework (43), nurturing work-life conflicts (6, 19, 21, 37, 43). A housekeeper helps working women have the opportunity to do professional activities and perform their motherly and marital duties in a more desirable way (4, 19, 37).

4.1.2.4. Support from Colleagues

Peer support means the extent to which the employed person is accepted by his or her coworkers and is emotionally or instrumentally supported by them (41). Collaborative support helps to better manage work and life difficulties (19). Therefore, the support of colleagues is one of the most important factors in helping prevent work-life conflicts (19, 21, 33, 41).

4.1.2.5. Support from the Manager

A supportive supervisor is able to increase the energy, enthusiasm, and positive attitudes of employees in the workplace and help create a collaborative work-oriented environment (12).

The supervisor’s perception of women’s commitments to family is a determining factor in work-life conflicts (19, 21, 23, 31, 32, 39, 43). Instrumental support from the supervisor, such as providing the necessary equipment for work at home (telecommuting), can reduce work-life conflicts for women (43).

4.1.3. Organizational Factors

4.1.3.1. Organizational Policies and Programs

Programs and policies that are designed to empower women to incorporate work and personal life are referred to as family-friendly policies (21), which enable women to better handle household responsibilities, parenting, or higher education and to improve work-life balance (4, 18, 19, 21, 23, 25, 30, 43). Flexible working hours, telecommuting, annual leave, hourly and maternity leave, daycare facilities, and vacations are among the family-friendly policies of organizations that help women to experience fewer conflicts between work and family roles (4, 19, 21, 23, 24, 28, 42, 43).

4.1.3.2. Working Hours and Job needs

Long working hours cause working women to have very little time for the family. In almost all studies, long working hours have led to exhausting lifestyles and work-life imbalance. Jobs that require long working hours (12, 19, 21, 23, 26, 28, 31, 33, 35, 38, 40, 42-44), have high urgency (44), impose great pressure on employees (6, 12, 19, 21, 23, 27, 32, 40, 42, 44), and require to be performed on holidays (12, 19, 23, 43, 44) increase the degree of work-family conflicts. Also, jobs that require forced overtime or long journeys away from the family reduce work-life balance (23, 31, 43).

4.1.3.3. Authoritarian and Autonomous Management Approaches

The management style encourages employees to put more effort and energy into achieving personal and professional aspirations and protects them from the hardships of work and life. Authoritarian management style, in which employees have the least role in determining their duties and working hours (12, 21), for example, forcing night and extra shifts (43) or on-call work shifts (44), leads to work-family conflicts for working women (12, 43, 44). On the other hand, with the increase in employees’ autonomy, women can have a better work-life balance (21, 26, 32, 33, 35).

4.1.3.4. Job Incentives and Facilities

Job facilities are defined as the organizational factors that can prevent job and family conflicts and create work-life balance and, therefore, a favorable work environment for employees (23). Appropriate work equipment and facilities (19), such as providing a safe kindergarten for employees’ children (28, 42, 43), proper transportation (19, 33), recreational facilities, and regular health examinations, can reduce work-life conflicts for women (38).

4.1.3.5. Role Overload

Role overload means that employees are overwhelmed by both their personal affairs and their work-related activities (19, 40). Role overload forces working women to work long hours, forcing them to sometimes take on homework (35, 39, 40). Having a real workload and understanding or believing that the workload exceeds one’s capacity leads to the mismanagement of other roles and increases work-life conflicts (21, 33, 39, 44).

4.1.3.6. Governing Organizational Culture

Norms and values related to the nature of the work, conceptualizing ideal employees, and employee relations collectively form the work culture that governs an organization (4). Organizational culture supporting collaborative work and segregation of duties can help reduce work-life conflicts experienced by women (4, 19, 23-25, 33). On the other hand, individual-centered organizational culture increases jealousy among employees and, subsequently, work-life conflicts (37).

4.1.4. Cultural Factors

4.1.4.1. Cultural Context

Society has high expectations of working women not only to play their social roles but also to fulfill their household chores effectively (4, 20). In traditional cultures, where the lifestyle of working women is viewed with denial or caution, women are required to meet full justice in all their roles (20). This justice is often fulfilled by restricting professional activities, causing anger, frustration, and disruption of work-life balance for working women (21, 24, 40). In addition, in societies where there is an individual-centered culture, it is difficult for women to achieve work-life balance (37).

4.1.4.2. Patriarchal Hegemony in Society

Different ways of socialization that exist in patriarchal culture lead to gender imbalance and unequal division of labor, making the family and society have unfair expectations of men and women (4, 36, 37). Thus, in these societies, despite the fact that women face intense work-life conflicts, men do not share roles in housekeeping responsibilities (4, 20, 37). In such societies, sons are raised as breadwinners (20, 37), where persuading men to participate in household chores is difficult and culturally distasteful (20, 37). The husband’s satisfaction and even his family play a decisive role in the continuation of women's professional activities. Therefore, women have to desirably perform household chores to maintain their jobs (20, 37), creating more work-family conflicts for them (20, 37).

4.1.4.3. Gender Bias

Gender discrimination and negative stereotypes institutionalized in some cultures cause women not to be taken seriously in their work affairs and forced to work harder than their male counterparts to achieve job promotion (20, 21, 24, 37).

4.1.4.4. Family-Friendly Culture

Society can help obviate work-life conflicts by redefining the role of working women. Men should be trained to participate in home and childcare activities in order to further benefit the family and the community (21). Implementing family-friendly policies at the national level, such as co-parenting, telecommuting, part-time work arrangements, and shortening working hours for working women, reduces conflict between women’s jobs and family roles (4, 21, 30).

5. Discussion

The present review was conducted to investigate the factors related to work-life conflicts among working women, identifying four groups of individual, interpersonal, organizational, and cultural factors.

The individual factors related to work-family conflicts included personality traits (e.g., self-control, optimal emotional state, etc.), health status (e.g., mental and physical health), and one’s skills (e.g., time management).

Those with a higher locus of internal control seek more social support, which cancels out the adverse effects of stress, especially at work. Additionally, these individuals are more likely to be engaged in health-promoting behaviors (e.g., increased exercise) and avoid unhealthy behaviors (e.g., smoking) (46). Hence, a higher locus of internal control results in better health and, ultimately, fewer work-family conflicts.

Personality traits, such as having positive attitudes, help women manage their psychological distress caused by family and work duties (4). Indeed, positive attitudes positively correlate with the strategies of reinterpretation, psychological well-being (e.g., resilience), and problem-solving but negatively with avoidance coping (47). In one study, for example, women noted that they tried to find positive aspects in their current situation based on the following motto: “If you can’t avoid it, enjoy it” (4).

Time management and self-assessment of one’s own ability are individual skills that are important to reduce work-family conflicts. Committing to time management increases one’s awareness of having control over work and family demands and reduces the feeling of having conflict between these areas. Time management through goal setting, goal prioritization, operational planning, and delegation of authority decreases the level of work-family conflicts. Importantly, many of these skills can be improved by training (48).

The second group of factors (i.e., interpersonal factors) included items related to the way that women worked with others, such as the husband, family, and supervisor. Women receiving adequate support from their husbands and relatives can play family roles more effectively and resolve work-family conflicts (4, 21).

According to the “Selection, Optimization, and Compensation” model, individuals can provide the available social support for spouses; therefore, women with a higher level of social support can spend less personal resource on work or inside the family, which reduces work-family conflicts. In addition, social support is positively associated with marital adjustment, and marital adjustment has a negative relationship with depression and anxiety in working women (49). Marital satisfaction and mental health inversely correlate with work-family conflicts. Thus, social support can act as a moderator of work-family conflicts (21). Moreover, being supported by the supervisor can improve job skills in less-skilled workers and decrease work-family conflicts. Also, coworkers can provide emotional support by listening to and empathizing with an employee and instrumental support by covering for their colleague who leaves early due to family issues (50).

Regarding organizational factors, most working women believed that they were forced to work long hours and sometimes to take their work home, which is a major barrier to work-life balance (19). Based on the compensation theory, people in one sphere are engaged in activities that satisfy their unfulfilled needs in another sphere (51). Therefore, if the job takes more from the person than it gives to her/him, family-work conflicts will rise. Long working hours and heavy work activities prevent women from personal growth (6). In jobs with a highly competitive atmosphere, women constantly compare their performance with their colleagues and try hard not to fall behind them, compromising their psychological well-being (6), which subsequently decreases their problem-solving coping and personal growth (47). In addition, it has been reported that long working hours have a negative impact not only on women’s health but also on the family’s well-being (52), leading women to face more family demands (6). This vicious cycle commonly increases work-life conflicts for women.

Long working hours mean being away from the family and consequently not having access to vital support resources (52). Social support is a moderator and predictor of work-family conflicts. Support by the supervisor and partner predicts work strain, thereby influencing work-family conflicts. Moreover, supervisor support buffers the relationship between marital problems and family-work conflicts. Encouraging and training family members, especially spouses and supervisors, to support working women improves their working conditions and reduces work strain, which is necessary to reduce work-life conflicts (53, 54).

Finally, the fourth group of factors influencing work-family conflicts included cultural determinants. In cultures where the traditional roles of genders have been preserved, men believe that women’s working outside the home interferes with their adequate fulfillment of household chores. Since these cultures do not defend women’s employment, men rarely help their wives do household affairs. Hence, women have to bear many household responsibilities alone, which makes it difficult to prevent work-life conflicts (20).

One study on 23,277 individuals across 37 countries showed that family-work conflicts were stronger among participants from individualistic cultures. In these societies, working women strive for the "I" and do not use the spirit of cooperation and collaboration to perform job duties, causing them more work-life conflicts (37). Jealousy of women is one of the most important challenges in individualistic cultures (55). In contrast, in collectivist cultures, people tend to link their personal goals with social responsibilities. The harmony advocated by collectivist cultures not only reduces interpersonal conflicts but also contributes to maintaining a stable state at work and in the family (56). More social support is provided in collectivist cultures, playing an important role in reducing work-family conflicts (55). Thus, the cultural background should be considered when developing and implementing policies that affect work-family conflicts.

5.1. Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, measures can be taken at the individual, family, organizational, and community levels to reduce work-life conflicts experienced by women. At the individual level, time management skills training is essential for working women. Families should also try to understand the situation of working women and learn how to support them. At the organizational level, improving occupational policies such as granting hourly leave, preventing overwork, and providing childcare facilities are recommended. At the community level, promoting employment policies, supporting working women, and training men to help their working wives can help reduce work-life conflicts.

5.2. Limitations

The most important limitation of this study was the lack of access to the full text of some seemingly qualified articles. In addition, most articles in this review had been conducted in Asian countries, and a few of them were from European or Australian countries. Therefore, the present study may not be a complete reflection of all cultures across the globe.

5.3. Suggestions

It is recommended that other researchers use our results when designing their interventions aiming to mitigate work-life conflicts in working women.