1. Background

Breast cancer disease is the most common cancer in the developed and developing countries according to the literature. Breast cancer is a major health problem in Iran (1, 2) and according to the latest national databases, age-standardized rate for breast cancer is 33.21 per 100,000 (2).

A recent study of breast cancer reported that the mean age for breast cancer in Iranian women is 5 years earlier compared to women from the developed countries (3) and increasing the trend of incidence is reported by the national cancer registry of project. Also, breast cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer deaths and it is estimated 14.2% of death (2). Previous research performed in Iran showed that breast cancer has a significant impact on women’s life (4).

Lack of awareness regarding risk factors, breast cancer screening methods, cultural taboos, feeling ashamed to talk about breast cancer, lead to late detection and development of breast cancer and death. The easiest early detection that women could do is breast self-examination (BSE) (5).

BSE is a simple, effective, and helpful method of breast cancer screening, which is appropriate for all women. In addition, it is inexpensive, and increases self-awareness (6). There is no evidence on the effect of screening through BSE and no supportive role for BSE in the early detection of breast cancer. While according to the Kotka Pilot Project, BSE has better detection and decreases mortality, however, Swedish, Russian, and Shanghai studies demonstrated no improvements in mortality decreasing (7).

However, it has been shown that BSE may be of special importance in countries where breast cancer is a rising problem, but where mammography services are almost absent (8). There is a lack of a population-based mammogram screening program in Iran. Therefore, it appears that BSE may be considered an attainable approach to empower women in the early detection of breast cancer.

BSE is helpful to women who have no access to other screening such as mammography. Despite the benefits of BSE, many women are inactive and different research has reported that the performance of BSE is low (9). The research suggested screening behavior is related to risk perception, benefit, barriers and reasoning processes that include personal and social factors and attitudes. Further studies are needed to understand the factors associated with the onset and maintenance of BSE throughout life.

The protection motivation theory (PMT) is a useful and social cognitive model for motivating individuals to use protective behavior. The PMT is frequently applied to breast cancer screening (10). According to the PMT model, women who have a higher perceived risk, and are susceptible to breast cancer and those who consider themselves at risk and serious disease would be more likely to affect regular BSE. Several studies suggested the effectiveness of PMT in Breast cancer screening (11-15). Although breast cancer is one of the few detected cancers in the initial phase, this level is very low in Iran.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine breast self-examination (BSE) behaviors applying protection motivation theory (PMT).

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study was done over a period of 6 months in health centers from May to October 2017. The statistical population of the study included 410 women aged 40 - 65 years old in Tehran, Iran. According to the rule of 5 - 10 individuals for each item (63 × 6), the sample size of 378 computer users was estimated. However, for more accuracy, the sample size was increased to 410 individuals (16). The multi-stage cluster sampling was implemented. First, the North, East, and Shemiranat networks were selected from 10 health networks of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Iran (SBUMS), and from each health network (n = 3), five urban health centers were randomly selected. Then from each health center (n = 15), 27 women over 40 years were randomly selected. Consequently, the sample size was computed at 27 × 15≈ 410.

Women who met the following were eligible due to the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria were a history or current diagnosis of cancer, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Additionally, the following exclusion criteria were considered: insufficient knowledge of the Persian language and insufficient physical and mental health to fill in the questionnaire. However, if someone suffered from any defect or disease interfering, they were excluded from the study. The demographic characteristics are presented by group in Table 1.

| Variables | Mean ± SD or No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 40 - 50 | 43.69 ± 2.7 |

| 51 - 60 | 53.35 ± 2.2 |

| Upper 60 | 61.9 ± 2.4 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 352 (88) |

| Single | 13 (3.3) |

| Widow | 26 (6.5) |

| Divorced | 9 (2.2) |

| Women occupation | |

| Housewives | 368 (92) |

| Working | 32 (8) |

| Education level | |

| Primary | 149 (37.3) |

| Secondary | 117 (29.3) |

| More than high school | 134 (32.9) |

Demographic Characteristics of Women

The research instrument included a self-reported questionnaire with 63 items. The questionnaire contained items of demographic information (4 items); knowledge questionnaire (20 items), PMT of breast cancer (37 items) and questions regarding BSE practice (2 items). The answers were ‘true’, ‘false’, and ‘don’t know’. The knowledge score was computed correct answers for all 20 questions (17). The PMT scale was developed in 1984 by McRae (18). In this study, first, a questionnaire was developed based on PMT and existing literature (12, 15, 19-27).

This questionnaire after a careful review and cultural adaptation and a few changes were made. The reliability and validity of the instrument were confirmed in the Iranian population (28). The final version of the questioner was average content validity (s-CVI/Ave) 0.80 that indicating adequate content validity. The reliability was determined by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The coefficient α for the instrument was as follows: knowledge = 0.81, perceived vulnerability = 0.83, perceived severity = 0.79, fear = 0.84, response efficacy = 0.76, response cost = 0.84, self-efficacy = 0.84, perceived rewards = 0.83, protection motivation = 0.90.

BSE behavior was assessed as self-reported in BSE within the past 1 month and the intended screening with the next month. The two following items assessed past behavior: “Have you done BSE in the last month?” (Yes/No,), and “How often have you done BSE in the last six months?” along with a seven-point scale (never once a month). Items with higher average scores + more frequency of past BSE behavior were collected (27).

All analyses were performed using SPSS 20 for the windows. One-way ANOVA, chi-square test, independent samples t-test, logistic regression, and Pearson correlation coefficient were applied. We set 0.05 as a criterion for statistical significance.

3.1. Ethics

The Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University approved the study (IR.TMU.REC.1395.328) all participants gave written informed consent. Institutional ethics approval (IRCT2017061134472N1) was obtained before the start of the research.

4. Results

Four hundred participants responded in this study with a response rate of 97.5%. Ten questionnaires were excluded (four questionnaires because of lack of participation, three questionnaires because of uncompleted filling, three questionnaires because of having breast problems). The mean age of women was 45.69 ± 5.5 years. The results showed 91.25% of women did not have enough knowledge about breast cancer (score < 12). Most of the women were married (88%) (Table 1).

The results of the Pearson correlation coefficient test showed that there was no significant relationship between age and perceived severity (r = 0.06, P = 0.17), perceived vulnerability (r = 0.07, P = 0.12), response efficacy (r = 0.01, P = 0.7), response cost (r = 0.09, P = 0.06), perceived rewards(r = 0.01, P = 0.7), and self-efficacy (r = 0.02, P = 0.63), respectively. While there was a significant relationship between age and fear (r = 0.141, P = 0.005). The results of the One-way ANOVA test showed that there was a significant difference between the marital status and the mean score of perceived severity and vulnerability, response efficacy and self-efficacy so that married people had higher scores (P ≤ 0.05). There was no significant relationship between the marital status and response cost, and perceived rewards (P ≥ 0.05). Also, the results of the One-way ANOVA test showed that there was a significant difference between the education level and the mean score of perceived severity and vulnerability and response efficacy, and self-efficacy (P ≤ 0.05), so women with higher education had a higher score in these structures.

According to logistic regression analysis; participants having knowledge on BSE practice were 3.46 times more likely to practice BSE [OR = 3.46, 95% CI (0.53 - 1.98)] compared with those less knowledgeable. Participants having a positive history of breast cancer in their family/friends were 2.59 times more likely to practice BSE [OR = 2.59, 95% CI (0.26 - 1.59)] compared with those having a negative history of breast cancer in their family/friends (Table 2).

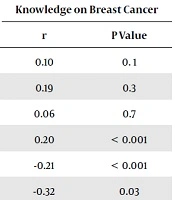

The results of simple bivariate correlation showed there was significant and positive correlations between the knowledge about breast cancer and self-efficacy in practicing BSE (r = 0.43, P < 0.001), response efficacy (r = 0.20, P < 0.001), and protection motivation (r = 0.25, P = 0.003) (Table 3).

| Scale | Knowledge on Breast Cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| r | P Value | |

| Perceived vulnerability | 0.10 | 0. 1 |

| Perceived severity | 0.19 | 0.3 |

| Fear | 0.06 | 0.7 |

| Response efficacy | 0.20 | < 0.001 |

| Response cost | -0.21 | < 0.001 |

| Perceived rewards | -0.32 | 0.03 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.43 | < 0.001 |

| Protection motivation | 0.25 | 0.003 |

Correlation Between Knowledge About Breast Cancer and Sub-Scale of PMT

The finding suggested there were significant negative correlations between the response cost and knowledge of breast cancer (r = -0.21, P < 0.001). Also, the results indicated there were significant negative correlations between perceived rewards and knowledge of breast cancer (r = -0.32, P = 0.03).

Furthermore, the results suggested there were no significant correlations between perceived vulnerability and severity with BSE practice. The results indicated there were positive and significantly correlated between the fear, response efficacy, self-efficacy, and protection motivation with BSE behavior so that means these structures were more in the practice group than the non-practice group (P < 0.001). While there were negative and significantly correlated between the response cost, the perceived rewards with BSE behavior means that these structures were less in the practice group than the non-practice group (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

| Scale | Mean ± SD | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSE Practice (80) | Non BSE Practice (320) | ||

| Perceived vulnerability | 9.75 ± 2.99 | 9.57 ± 3.05 | 0.5 |

| Perceived severity | 5.50 ± 2.22 | 5.82 ± 2.12 | 0.2 |

| Fear | 15.70 ± 7.2 | 12.95 ± 6.97 | 0.001 |

| Response efficacy | 15.92 ± 3.10 | 17.46 ± 2.62 | < 0.001 |

| Response cost | 21.33 ± 7.2 | 23.02 ± 6.38 | 0.041 |

| Perceived rewards | 8.5 ± 2.83 | 9.29 ± 2.54 | 0.01 |

| Self-efficacy | 12.10 ± 1.1 | 9.2 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Protection motivation | 2.64 ± 0.48 | 2.19 ± 0.80 | < 0.001 |

The Mean of the PMT Subscale on Breast Self-Examination

5. Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to determine breast self-examination (BSE) behaviors applying protection motivation theory (PMT). In our sample, breast cancer awareness was low that it leads to late in referring to health centers. Due to the findings, only 14.5% of the participant ever heard about BSE, 8.7% had enough knowledge about breast cancer, and 91.25% had poor knowledge, while Baena-Canada et al.(29) reported that enough knowledge was 9.7% and in the study of Yadegarfar et al. (30) low knowledge was reported 55.7%. World Health Organization (WHO) recommends promoting knowledge and encouraging in the community through early detection and diagnosis of breast cancer in all women, especially women aged 40-69 years old who are returned health care centers or hospitals (31).

In many findings, BSE behavior was determined by the knowledge of women or having information on diagnostic methods of breast cancer (32). In our study, it found the knowledge is a significant variable in BSE. Similarly, in Hyun’s research, it was suggested that women who are experienced to carry out BSE have a better level of knowledge of breast cancer (33). Breast cancer occurs in Iranian women earlier (34), so to enhance awareness about breast cancer screening can help in deducting mortality. It seems lifestyle changes and socioeconomic have a positive relationship with breast cancer (35). In this study, participants who had a positive history of breast cancer in their family/friends were more likely to practice BSE compared with those had a negative history. Similarly, some studies suggested this finding (36, 37). A positive history can act as a trigger that drives a person to take up a given breast cancer prevention behavior.

In this research, only 20% of the females reported doing regularly and monthly BSE. Similarly, some studies have indicated less than half of the participants really practice BSE monthly (38, 39). In the study of Mekuria et al. (32) performance of BSE was reported 13.4% and in the study of Badakhsh et al. (40) it was reported between 2.6% to 84.7% and an average 21.9%. While in the Didarloo et al. study, 24.6% (41) and in the study of Ertem and Kocer (42), 52% of women practiced BSE. In our study BSE performance was reported lower than the average. It seems one of the reasons this finding was lower literacy of women.

In the present study, the main source of information was the health care team. This indicates that health workers are effective. So that in the systematic review of Bouya et al. (43) it was reported that the most important sources of information were the healthcare team and it was confirmed in similar research. Nearly 21% of women have obtained information on breast cancer from TV/radio. Also, education based on the internet and social networks bring awareness of women effectively. In the current study, one of the sources of information was the Internet (26.5%). Tortolero-Luna et al. (44) described cancer information-seeking behavior and they reported that the Internet was the frequent sources of information about cancer (28.1%). The results showed there was no significant relationship between BSE practice and demographic variables (except for educational level). Similar to our study, in Jirojwong et al.’s study (45) and Dundar et al.’s research (46), it was explained that socio-demographic variables were not effectual in BSE practice.

Similarly, the results of studies carried out by Fry and Prentice-Dunn (15), Boer and Seydel (47), Floyd et al. (19), Hodgknis and orbell (23), suggested the PMT is a beneficial framework to recognize factors that influence BSE for Iranian women. In this study perceived vulnerability and severity were not significant in explaining the BSE practice on a regular basis, but increased self-efficacy, response efficacy, and reduced BSE response cost and perceived rewards were significantly associated with BSE behavior. In Jordanian and U.S (48), Turkish (46), and Chinese (49) studies the perceived severity of women was reported as a non-significant predictor of BSE. It seems perceived severity is not a good predictor for breast cancer because this disease may be perceived by all women as an important and serious event, affecting the psychological, physical, and social aspects of life (46). Protection motivation was found to be a significant factor for BSE practice parallel to the results of Vahedian Shahroodi et al. (12) and Lee Champion (17).

Response efficacy was a significant variable predicting BSE practice. According to the finding of American studies, women who have more perceived response efficacy in BSE were more likely to practice BSE behavior (50, 51).

In our study self-efficacy was a significant factor for BSE practice and women who performed BSE on a regular basis had higher self-efficacy levels than non-practitioners women. The other studies indicated the various degree relationships between self-efficacy and breast cancer screening (52-54). In these studies, women who reported more self-efficacy in BSE were more likely to practice BSE regularly. In the current study, women who reported more fear of breast cancer were more likely to practice BSE regularly. Chen and Yang (55) reported similar results. Various studies have described the behavior of fear with both inhibitory and stimulating effects (56).

The present study has several strengths. This was one of the theory-driven studies examining breast cancer. Our findings provide evidence for the use of PMT in breast cancer prevention, which can be used as a framework for educational interventions in the field of breast cancer. Our study had several limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional design, so causal conclusions cannot draw. The sample of the research was middle-aged women in an urban area in Tehran, which does not necessarily reflect what happens among women in rural areas. So, the results of the study cannot be generalized to a larger population in Iran. Furthermore, the data were collected by a self-reported questionnaire, which may be a source of bias. Further studies with adequate confirmation of self-reported information built into their design are recommended.

5.1. Conclusion

Overall, the findings of our study suggest health care providers may consider PMT as a framework for developing educational interventions aimed at improving women’s BSE behavior.