1. Background

Today, cancer is the third most prevalent cause of death after heart disease and driving accidents in Iran. According to the latest estimates, the annual incidence of cancer in Iran is about 107 people per 10,000 people (more than 80,000 people, against 75 million Iranian population). It is anticipated that in the coming decades, this will display an increasing trend due to the increase in environmental pollution, increase in the number of the elderly (with the population becoming older), and population growth so that cancer will be one of the major health problems in Iran (1). Given that cancer is a life-threatening disease, it can affect the individual lives from different aspects and create a wide range of issues and problems as a result of his/her disease trend (2). Since each person has different concept of the disease, patients with cancer face numerous changes and challenges in different fields of life (3). These patients have different needs after facing the diagnosis of the disease (4). One of these needs is spiritual needs (5).

Spirituality is the essence of human existence (6) and causes humans to experience the excellence and continuity of existence beyond the self or to be connected with other humans and, in both, establishes vertical relationships (with the top existence) and horizontal (with other people) and go beyond the boundaries of the self. This experience imparts direction to life and gives meaning to death (7, 8). A person’s spirituality becomes clearer in times of need and during crises. Disease is among these crises (4, 9).

Cancer increases patients’ spiritual needs dramatically, because their spiritual faith is endangered, personal communications are disrupted due to uncertainty about the future, compatibility mechanisms seem insufficient, and hospitalization also gives them a feeling of loneliness. In a word, it can be said that a spiritual crisis emerges in a person (10, 11). This crisis causes an imbalance in and disharmony of thought, soul, and body (12). Patients coping with serious illnesses, such as cancer rely on the spiritual demission and spiritual compatibility; this is a powerful way they use to deal with the disease (13). The willingness to go in for religion and spiritual resources can be used as a consistent psychological-social compatibility approach after the disease is diagnosed (4, 14). Based on Florence Nightingales philosophy of care, spirituality exists inherently in humans, and it is the deepest and strongest recovery source. Therefore, one of the responsibilities of nurses is to pay attention to the spiritual dimension of care and to provide a healing environment for patients (15). Care providers are required for patients with cancer as part of holistic care and they should gain the skills necessary to identify the spiritual needs of patients (16).

Narayanasamy sees the assessment of spiritual needs as an essential component of comprehensive care in nursing (17). However, many of the patients are applicants for spiritual care, but do not get care providers (4, 18). The response to the spiritual needs of patients with cancer is at a minimum level or has been overlooked (4, 19). Since the identification of spiritual needs has been held up as a critical element in providing culture-based care, it is necessary to obtain a better understanding of the amounts of spiritual need. The response to this need requires its measurement (20). There are, now, 4 tools for evaluating spiritual needs in the world, which include questionnaires on spiritual need; Bussing et al. (2010), (21) Sharma et al. (2014), (22) Yong et al. (2008) (23), and Galek et al. (2005), (24), which were designed based on the culture prevailing in their respective countries.

Owing to the religious nature of people in Iran and the prevailing religious beliefs among patients in Iranian society, there is no possibility of using tools designed on the basis of other religions to assess Iranian patients’ spiritual needs (25). Despite the expression of spiritual needs to consider the unmet spiritual needs of patients (22), no special attempt has been made to describe and measure the spiritual needs of patients with cancer in Iran.

1.1. Conceptual Model

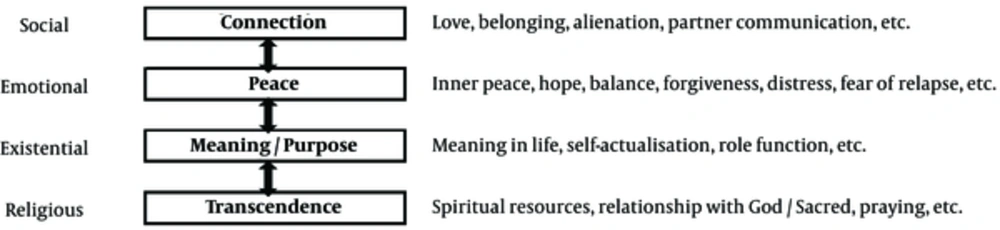

The model used in this research is based on the pattern of spiritual needs that was designed by Bussing and Koenig in 2010. This model has 4 main dimensions: of connection, peace, meaning and purpose, and transcendence; these dimensions are at the heart of psychological, social, emotional, existential, and religious needs (Figure 1). This model is considered a framework for future research and clinical performance. By identifying the spiritual needs of patients, care providers, and contact cases, patients can be aided to fight against chronic and dangerous diseases (19) (Figure 1).

2. Objectives

This study was conducted with the aim of the development and psychometrics of “spiritual needs assessment scale of patients with cancer”.

3. Methods

This research has a mixed methods exploratory design, which was done to design and determine the psychometric features, the spiritual needs scale of patients with cancer, in 2 stages: qualitative and quantitative. In the qualitative stage of the research, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 18 patients with cancer to explain the spiritual needs of patients and develop scale items. Participants who were selected as purpose-based were over 21 years, were aware of their disease, and were able to connect with others. Also, the definitive diagnoses of cancer had been made for them by doctors. Six months was spent since the notification of their disease and they had no history of mental disorders.

These patients were selected among the patients referred to the cancer institute of Tehran (the capital of Iran), which is the biggest cancer centre. The researcher first introduced himself/herself and objectives of the study to each individual participant and assured him/her that all the information and content would remain confidential. The researcher, then, proceeded to obtain written consent of the samples for the study in order to meet ethical considerations. All interviews were performed in a solitary room with the participants’ consent. The semi-structured interview was a method of data collection. Phonographic recordings were used to increase the accuracy in interviews. Each interview started with a general question: What is the effect of disease on emotions, behaviour, or your needs? Then, more specific questions were asked, such as: Since you have been sick, what do you need more, you feel? The interview sessions lasted from 40 to 90 minutes. Interviews were written down accurately and verbatim, and were analysed using the content analysis method at the same time with the data collection process. The sentences of participants were, then, taken from the interview content such that each was in the form of a phrase meaning, typically suggesting a semantic unit. The terms that did not exist in the qualitative section were added to the item pool by review of literature, papers, and books related to spirituality and spiritual needs.

Reliability and validity were assessed in the quantitative section of the study. Methods of content validity, formal, and structure (factor analysis) were used to assess the validity of the spiritual needs scale. Content validity ratio (the amounts of each of the tool items that were essential) and content validity index (the rate of relevance of each of the items) were evaluated for the content validity of the spiritual needs scale. In the CVR assessment, statements were given to 15 university professors, who had expertise in the fields of spirituality, cancer, and tooling to determine the necessity rate of each statement on a three-rating scale, including it is essential, it is useful but not necessary, and it is not necessary. This ratio has higher objectivity compared to other methods to determine validity (26). After applying the comments and deleting phrases that had lower content validity, the content validity index of tools (the relevance rate of each of statements) was investigated through a poll of 15 experts. In order to assess the ease of understanding the expressions, the scale was, then, given to 10 patients diagnosed with cancer to express their opinions about its items. Then, internal scale consistency was determined in a sample of 20 patients.

A total of 400 patients with cancer were selected among patients with cancer referred to the cancer institute of Imam Khomeini Hospital to comply with the inclusion criteria (mentioned in the qualitative section). After completing the consent in a study to determine the validity of structure and performing the factor analysis, 5 to 10 samples per item are enough or even 3 samples for each item of tools are enough (27). The validity of the structure of the spiritual needs scale was performed with the help of the exploratory factor analysis by using SPSS 18 to determine the number of samples required.

Two ways of determining the internal consistency (calculation of Cronbach’s alpha) and test- retest reliability were used to determine the reliability of spiritual needs scale. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated for the total scale in each dimension and for each factor in a sample of 400 patients. Interclass correlation coefficient was investigated between scores of 2 scales as well as in a sample of 20 people and within 2 weeks. The code of ethics was taken from the International Branch of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

4. Results

The findings are presented in terms of both qualitative and quantitative sections.

4.1. Qualitative Section

Participants in this study were 18 patients, including 9 males and 9 females, aged 22 to 72 years, diagnosed with cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, lung, leukaemia, lymphoma, Hodgkins disease, breast, uterus, and ovary.

The analysis of the obtained data leads to the extraction of 1250 codes in the first step, 35 sub-categories and 12 categories, which formed four themes as follow: Communication, Peace, Meaning/purpose, and Excellence.

4.2. Quantitative Section

The findings from the qualitative section (semi-structured interviews with patients with cancer) and the existing design scale were used to determine the items of spiritual need scale. The total items of the spiritual needs scale at this stage had an item of 5 options (strongly agree, agree, no comment, disagree, and strongly disagree). CVI and CVR were used to determine the content validity of the spiritual needs scale of patients with cancer.

The score of the content validity ratio and opinion of experts about the possibility of merging some phrases in other phrases to reduce phrases were evaluated at this stage. Replies were calculated based on content validity ratio formula so that the score of 54 phrases was higher than the number in the Lawshe table (0.62).

It was carefully assessed to find out that whether or not there is another phrase that shows almost the same features as the phrases with a score of content validity ratio less than 0.62 that must have been removed or phrases that were integrated into other phrases. To determine the content validity index of tools, attempts were made to remove the items, which had relevance rates less than 75% based on this index (28). Eleven phrases were, thereby, removed (though 9 phrases had content validity index of 0.80 and 2 phrases had content validity index of 0.70) due to replication, after the number of comments from evaluators and the number of phrases of tools reached 43. A number of statements were also amended.

At the end of the validity stage of the content, scale items were reduced from 54 items to 43 items. The evaluation of items of tools patients in the stage of face validity was undertaken to remove 2 statements: Do you like to wait for death during the disease? as well as Do you like to think about your fate after death at the time of disease? And the number of items reached 41. After determining the validity of the content and face validity, internal consistency of the designed tool was determined for preliminary in a sample of 20 patients with cancer, as α = 0.79.

The demographic characteristics of patients in the stage of determining the validity of structure have been recorded in Table 1. Sampling adequacy was investigated by the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test (0.84) and Bartletts test was used to determine that there is a significant difference between the correlation matrix obtained with zero and the factor analysis can be justified on the basis of that, which was obtained at 3787.006 (P < 001).

| Variable | Classes | No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 232 (58) |

| Male | 168 (42) | |

| Marital status | Single | 61 (25.12) |

| Married | 288 (72) | |

| Without spouse | 51 (75.12) | |

| Risk of other chronic diseases | It has | 88 (22) |

| Does not have | 312 (78) | |

| Level of Education | Illiterate | 67 (75.16) |

| Under-Diploma and Diploma | 236 (59) | |

| Collegiate | 97 (25.24) | |

| Occupation | Free | 64 (16) |

| Employee | 70 (5.17) | |

| Housewife | 141 (25.35) | |

| Retired | 27 (75.6) | |

| Worker | 43 (75.10) | |

| Unemployed | 55 (75.13) | |

| Location | Tehran | 137 (2.34) |

| City | 212 (8.65) | |

| Time cancer diagnosis | 7 to 12 months | 197 (25.49) |

| 13 to 24 months | 129 (25.32) | |

| 25 to 36 months | 38 (5.9) | |

| 37 to 48 months. | 11 (75.2) | |

| 49 to 60 months | 9 (25.2) | |

| More than 60 months | 16 (4) | |

| Type of cancer | Breast | 56 (14) |

| Digestion | 120 (30) | |

| Haematology | 93 (25.23) | |

| Uterus and ovaries | 50 (5.12) | |

| Bone | 20 (5) | |

| Lung | 23 (75.5) | |

| Prostate | 8 (2) | |

| Other | 30 (5.7) |

Demographic and Clinical Features of Patients with Cancer Participating in the Research

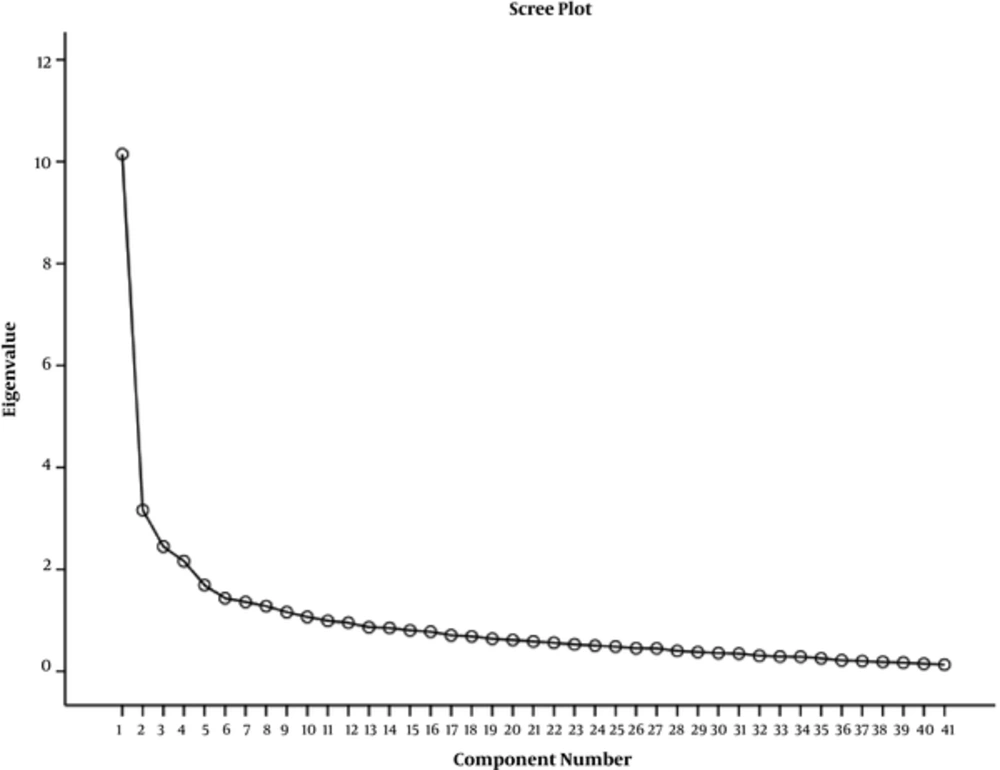

In the first step, the factor analysis revealed 10 factors with eigen value above 1 which explained 61.4% of the variance. Eventually, 5 factors were accepted that express 48.2% of the variance in order to simplify the scale and facilitate the interpretation and naming the factors. In other words, the spiritual needs scale of patients with cancer was divided into 5 sub-scales. Three items were excluded as they had factor load less than 0.3. The first factor, religion, had 9 items that represented 12.55% of the variance. The second factor, meaning and purpose, represented 11.12% variance and it had 7 items. The third factor, peace, represented 10.8% of the variance and contained 10 items. The fourth factor, connection, explained 7.13% of the variance and it had 6 items. The fifth factor, named support and nationalism, represented 6.62% of the variance and had 6 items. The scree plot also confirms 5 extracted factors (Figure 2). So, applying the factor analysis method, an acceptable structure validity of the spiritual needs scale in 5 subscales was shown.

After performing factor analysis, Cronbach’s was alpha coefficient was calculated for the total tools and also for any factor in 400 samples of patients with cancer who had completed the questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the whole scale with 38 phrases as α = 0.91. Also, Cronbach’s alpha was brought for each of the 5 dimensions of scale in Table 2.

| Dimensions | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|

| Religion | 0.88 |

| Meaning and purpose | 0.77 |

| Peace | 0.80 |

| Connecting | 0.74 |

| Support and nationalism | 0.67 |

Cronbach’s Alpha for Dimensions of the Spiritual Needs Scale of Patients with Cancer

The retest was carried out to determine the retests of the scale. Intra-class correlation coefficient between the scores of 2 scales was obtained at ICC = 0.84 (P < 0.001).

5. Discussion

To carry out interventions to meet the spiritual needs of patients with cancer and measure the effectiveness of these interventions, a scale is necessary to measure this concept. The aim of this study was to design and evaluate the psychometric properties of the spiritual needs assessment scale of patients with cancer. This scale was designed as based on the conceptual framework of spiritual needs of Bussing and Koenig (19). Items of scale were driven to analyse interviews conducted with patients having cancer and to review the surveys and available related scales, and were classified on the basis of the spiritual needs model of Bussing and Koenig. After applying the comments of experts in the validity stage, the number of phrases of the tool reached 43, and the coefficients calculated for content validity rate and content validity index showed that the spiritual needs scale of patients with cancer has good content validity.

Toolmakers use the calculation of content validity ratio and content validity index to validate the tools (26, 28, 29). Written comments of experts were used to verify the face validity during content validity and, accordingly, necessary amendments were done in terms of writing and Persian grammar, clarity, and simplicity of items. Thus, the face validity of scale was also confirmed. In addition, 10 patients also examined the scale. Two phrases were deleted at this stage that had been included earlier: Do you like thinking of death at times of disease? as well as Do you like thinking of your fate after death? It seems that these 2 phrases, belonging to the final days of life and being close to death, remind patients that responsiveness to these 2 phrases was very difficult for them.

Death is a complex concept as it is the biggest problem and event of life that can be associated with much pain and suffering. Loving the world and various worldly manifestations is obvious, natural, instinctive, and innate. This means the interest of humans in life is not something that has been created by training, inculcation, or habit. On the other hand, the researcher believes that loving the world and desire to live is a positive matter and a sign of mental health. However, in Islamic culture, death is considered a presence in the heavens and return to the Lord and responsiveness time to actions; it seems taboo in Iranian culture in relation to death causes patients to avoid thinking about death and, thus, suppress it in their mind (30). Hope can be identified as another reason in patients with cancer. Many studies have shown that Iranian patients with cancer, thanks to their religious nature, have high degrees of hope. This aspect is highlighted at the time of the disease (31-34). Lack of end-of-life care can be identified as another reason why they have no desire to respond to the above question.

One phrase was related to the opinion of patients in relation to death in the tool designed by Bussing et al. (21). Perhaps it is an advantage for patients who easily accept death which can be attributed to current palliative cares as well as end-of-life care in western countries

The structure of validity assessment of spiritual needs scale by factor analysis method shows being multi-factor (existence of 5 factors) of scale. These factors include religion, meaning and purpose, peace, connection, and support and nationalism. At this stage, 3 phrases were removed due to low load factor and that the number of phrases reached 38. While removing these phrases, the phrases overlapping in the scale was noticed.

It was observed that phrase 11 (I need to be alone) with the phrase (I like) I want to be in a quiet place (solitude), phrase 29 (I need my life to have purpose) with all phrases in the subscales of meaning and purpose, phrase 32 (I think about my future) with phrases 21 (I accept my own disease) and 25 (I am not to be dependent on others to do my work) and phrase 26 (I am ending well) and phrase 27 (to be respected for my opinions) and phrase 28 (I participate in decisions relating to myself) and phrase 29 (I have life with purpose) and 30 had overlapping with (I know the value of remaining life and use my opportunities).

One of the differences in this scale with existing tools (22-24) was the emphasis of the designed scale on the religious dimension so that 9 phrases related to this dimension have had the highest load factor among phrases compared with other dimensions. Spirituality is thought and belief broader than religion, though in many people, this concept is declared and evolved through religious rituals, such as prayer (35).

In this study, the factor load in phrases related to the religious dimension can be high because of the structure and religious texture of the Muslim community in Iran. The results of this study showed that Iranian Muslim patients achieve spirituality through religion, even when they are not religious people, and show their spirituality in the form of religion; perhaps it had been so from birth due to the cultural texture and religious environment ruling their training situations from birth.

The reliability of the spiritual needs scale of patients with cancer was also investigated: reliability in order to ensure accuracy of information and to maintain repeatability. A suitable method is Cronbachs alpha, which is nowadays more and more used to calculate the internal consistency (36). In the present study, Cronbachs alpha coefficient was obtained α = 0.91. The reliability of retests of this scale was done in addition to the assessment of internal consistency by using intra-class correlation index in 20 patients with a time interval of 3 weeks, which due to the achievement of the coefficient of ICC = 0.84, the scale of spiritual needs of patients with cancer had retested well (26).

The extraction of the phrases of tools and, then, the assessment of its psychometric properties were carried out in accordance with the definition of spiritual needs presented in the literature. In the end, a scale with 38 phrases was presented, which had good validity and reliability. This scale often covers subscales and the other tool phrases in this area. Such a finding is not unexpected, since spirituality is considered a universal concept that has common features in all people and communities (37-41). In some cases, it might be an approach that one person applies to the assertion of his/her spirituality: not to be conventional in other communities or among other people. Even among different religions, there can be differences between symbols and rituals that reflect the spiritual aspects (42, 43). According to the researcher, some approaches have adaptive aspects and are strongly influenced by people trends and traditions prevailing in the society. Sulmasy believes that many people make obvious their spirituality in the form of religious activities, but others show their spirituality in their relations exclusively with nature, music, art, philosophical beliefs, or communicate with friends and family (43).

In some cases, these approaches were also primarily not stated by Iranian patients as a major and important need (these phrases such as gift to someone, listen to music and have fun, experience nature and understand it, think about life after death, think of death, imagine purpose for life, and talk with a clergyman about fears and concerns).

In addition, the scale designed in this study has considered some characteristics that had been important for Iranian patients with cancer in accordance with their experiences, perceptions, feelings, and religion, but does not exist in other tools (have an ending that is good, access to the necessary facilities for religious methods, recourse to religious leaders, amplify your religious beliefs), which can be attributed to the culture and religion prevalent in the country. Religious patients express their existential and spiritual needs in the form of religious words, while non-religious people express these in a humanitarian and existential template form. Theoretically, though there is differentiation among psychological, spiritual, and existential needs, it is clear that these needs are interconnected.

The present study does have limitations. Though the cancer institute of Tehran, the biggest cancer centre in Iran, is a referral centre for patients with cancer from all over the country, one should be cautious in generalizing the results.

5.1. Conclusions

Although the scale presented in this research is the first basic tool designed for psychometric assessment of the spiritual needs of patients with cancer in Iran, like all newly designed tools, it obviously has numerous deficiencies. More studies, using these tools for assessment of patients’ spiritual needs in different regions of the country and different population, can be helpful to modify it.