1. Background

Hospice palliative care (HPC) is a special type of care, in which patients with life-threatening illnesses and patients, who live in the final stages of their life, will benefit from therapeutic, mental, and spiritual supports. HPC is focused on pain control and other symptoms management so that patients, who are near the end of their life, feel more comfortable (1). The goal of HPC provision is to increase the patients’ quality of life and to support their families and caregivers (2). Hospice movement, one of the greatest successes of modern medicine, began in the result of Dr. Sanders’s efforts in England (3) and, then, was expanded in Australia, New Zealand (4, 5), India (6), and Japan (7). Over the past two decades, the number of HPC centers, as well as the number of End-of-Life (EOL) patients, who use their services, are rapidly increasing (8).

However, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2014, access to EOL care and regional context-based guidelines related to providing it has been very limited in the Middle East region and requires special attention (9). In Iran, the demand for EOL care is increasing concerning the aging population and the rise in cancer statistics, as well as recent advances in treatment and care. Most patients and their families would like to receive optimal care in hospitals and clinics. However, they do not have access to HPC. Besides, there are not adequately trained human resources in this felid, while recent research emphasized the establishment of centers providing HPC services (10, 11). Furthermore, in recent years, the policy-makers emphasized improving the patients’ quality of life and their families and providing supportive and palliative care as an important part of health care services. Also, the National Comprehensive Palliative and Supportive Cancer Care Program is developed, in which the need for various levels of palliative services such as HPC has been raised (12). Furthermore, the announcement of Deputy of Nursing of the Ministry of Health (MOH) in May 2017 to the universities of medical sciences across the country on licensing to the home care founders to establish hospice centers is strong evidence that proper planning on HPC is a perceived need in the Iranian health system. Designing an appropriate care framework or model for the provision of HPC services is a necessity (13). Given the lack of adequate experience in providing HPC in Iran, basic studies are required to identify probable barriers and appropriate preventive managerial actions. So, it is useful to review and use the successful experiences of other countries to reduce the probability of failure (14). In this regard, comparative studies and international comparisons can generate useful information about provided services in each country by comparing similarities and differences. Also, they create a general understanding of the intended issue. Besides, general conclusions and suggestions can be extracted to improve HPC services and to develop regional and national policies.

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study was conducted to describe and compare HPC delivery systems and to investigate the nature and structure of them in the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, Australia, Japan, India, Jordan, and Iran.

3. Methods

In this descriptive-comparative study, HPC delivery systems in the UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, India, Jordan, and Iran were reviewed and compared to describe and identify the similarities and differences among them from 2018 to 2019. The countries were selected purposefully based on the Economic Intelligence Report (EIU) about the quality of death index in 2010 (15) and 2015 (16). In sum, 80 surveyed countries are located in 5 geographic regions of the world (America, Asia-Pacific, Europe, Middle East, and Africa). According to the results of the preliminary search, the possibility of access to information was identified. Then, considering the ranking of the surveyed countries, the sample was selected as follows: the UK (from the European region and ranks first as the origin of the HPC, and pioneer in the development of it), Canada (from America region and ranks 9th), Australia (ranks second), Japan (former region due to promoting the rank than before; from 23 to 14), India (from the Asia-Pacific region, due to downgrading the rank; from 40 to 67), and Jordan (due to gaining rank 37 among 80 countries, being located in the same geographical region with Iran, similar health system conditions, the proximity of social, economic, cultural, and religious conditions). No country was selected from the Africa region given that the lack of sufficient information.

3.1. Conceptual Framework

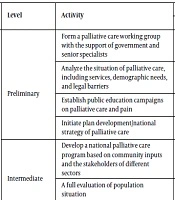

The conceptual framework of the present study is based on the WHO guideline titled “Planning and Implementing Palliative Care Services: A Guide for Program Managers.” The guideline includes 6 axes on designing and developing a palliative care (PC) system. The activities in each axis are classified into 3 levels; initial, intermediate, and advanced. Based on this framework, a PC system should be assessed in terms of policy-making, funding, provision of services, human resources development, access to medicine, and information and research.

In the policy-making axis, the following activities are required: the formation of PC working group with the advocacy of government and experienced experts, the situational analysis of country on PC services, population needs, regulatory barriers, public education about PC through forming campaigns, the development of a national PC program and the expansion with the participation of stakeholders, the development of protocols and guidelines, and the integration of PC at all levels of the health system.

The financing resources include activities such as allocating costs from health budgets, bringing PC services into public health insurance packages, providing free-standing PC services for all eligible patients, and providing social support for caregivers.

In the axis of service delivery, the PC system should be assessed on items like starting PC services for defined community and patients with a life-threatening condition, establishing referral and coordination processes to create a PC network in a determined community or district, identifying patients with life-threatening illnesses at different levels of care, developing PC services in hospitals, building home care and cancer centers for all patients with life-threatening conditions, presenting Primary Health Care (PHC) services to apply the palliative approach, reinforcing PC network through integrating between levels of care, and establishing long-term care centers.

The third axis, human resources development, refers to doing the following activities: training clinical leaders through Training of Trainer (TOT) within the country and abroad, holding training courses on PC for health professionals, social workers, and volunteers, creating a reference training center in the country, integrating the PC subject into the medical and nursing curriculum, training physicians and community nurses, pharmacologists, and other health prescribers to use morphine safely, and building a specialized PC discipline for physicians and nurses at major universities.

At next axis access to medicine is checked via a review of existing laws in the country and available medicines, preparing a list of PC essential drugs following the WHO guidelines, training doctors at identified PC centers regarding prescribing narcotic drugs, reforming laws and regulations for easy access to opioids aligned with international narcotic drugs conventions, estimating the population’s demand for PC essential medicines, identifying supply and distribution of controlled drugs, ensuring the availability of oral morphine in the country, progressive eliminating of costs, prescribing and supplying chain obstacles to access to opiates, ensuring equitable access to opioids pain killers to all of the demand patients, and assuring the availability of a reliable supply of all essential PC medicines to meet the needs of all regions of the country.

Finally, in the information and research axis, creating a basic information system for monitoring and evaluating activities at different levels, establishing a high-level center for interdisciplinary research, as well as quality control of services, determining individual’s access to services and developing PC Ph.D. program will be reviewed (17).

3.2. Data Collection

Firstly, a literature review was conducted to obtain basic information on health care and HPC systems of selected countries. The keywords were consistent with MeSH and comprised of “End of Life Care”, “Hospice”, “Supportive Care”, “Palliative Care”, “Terminal Illness”, “Patient”, and “Cancer”, which were searched separately and in combination with each other. Also, the mentioned keywords were searched in combination with terms such as “Care, Outcomes, Costs”, “models of service provision and policy”, and the names of intended countries (UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, India, and Jordan).

The national (SID, Magiran, and Iranmedex) and international (Scopus, PubMed, Web of Sciences, ProQuest, CINAHL, MedlinePlus, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar) databases, as well as important specialized journals on palliative and hospice care, were searched. Also, scientific and administrative documents, reports, and the website of the WHO, government, and other valid sites in each country were reviewed. Besides, major national and regional websites associated with organizations that are active in the field of cancer and HPC were explored in detail. Data on policies, guidelines, and HPC models were accessed both from the above-listed resources and existing reports called “Minimum Data Sets” (MDS). Moreover, the websites of 3 hospice centers were reviewed in each country. Other information is outlined in Table 1. After reaching the existing HPC delivery models in the selected countries, the HPC delivery situation in Iran was also examined.

| Database | Details |

|---|---|

| Specialized Journals | American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (Sage Journals) |

| Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing (Wolters Kluwer) | |

| Journal of Palliative Medicine (Centre for Bioethics, Clinical Research Institute of Montreal) | |

| Journal of Palliative Medicine (Sage Journals) | |

| Journal of Pain and Symptom Management (Elsevier Publishing) | |

| Journal of Palliative Care (Sage Journals) | |

| Palliative & Supportive Care (Cambridge University Press) | |

| Indian Journal of Palliative Care (Wolters Kluwer) | |

| Death Studies (Brunner – Routledge (US)) | |

| Major international, national, and regional websites and databases | England |

| National Health Service (NHS): http://www.nhs.uk | |

| Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland (APM): http://www.apmonline.org | |

| Hospice UK: http://www.hospiceuk.org | |

| National Council for Palliative Care (NCPC): http://www.ncpc.org.uk | |

| Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance (WPCA): http://www.thewhpca.org | |

| Dying Matters: http://www.dyingmatters.org | |

| Omega (National Association for End of Life Care): www.omega.uk.net | |

| National Cancer Research Institute: www.ncri.org.uk | |

| National End of Life Care Intelligence Network (NEoLCIN): http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk | |

| Royal College of Physicians: http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk | |

| Royal College of Nursing: http://www.rcn.org.uk | |

| British Association of Social Workers (BASW): http://www.basw.co.uk | |

| Center for Workforce Intelligence (CFWI): http://www.workforceintelligence.org.uk | |

| Macmillan Cancer Support: http://www.macmillan.org.uk | |

| Marie Curie Cancer Care: http://www.mariecurie.org.uk | |

| Sue Ryder: http://www.suerydercare.org | |

| Cruse Bereavement Care: http://www.crusebereavementcare.org.uk | |

| Skills for Health: http://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk | |

| Canada | |

| Ministry of Health and Lon-Term Care: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/ | |

| Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association (CHPCA): http://www.chpca.net | |

| Canadian Institute for Health Information: http://www.cihi.ca/en | |

| Canadian Virtual Hospice: http://www.virtualhospice.ca | |

| Public Health Agency of Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health.html | |

| Royal College of Physician and Surgeons of Canada: http://www.royalcollege.ca | |

| Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physician: http://www.cspcp.ca/en | |

| Canadian Nurses Association (CAN): http://www.cna-aiic.ca/en | |

| Australia | |

| Palliative Care Australia: http://palliativecare.org.au | |

| Australian Government, Ministry of Health: http://www.health.gov.au | |

| Western Australia Cancer and Palliative Care Network: https://ww2.health.wa.gov.au | |

| National Health Workforce Data Set (NHWDS): https://www.aihw.gov.au/about-our-data/our-data-collections/national-health-workforce-dataset | |

| Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW): https://www.aihw.gov.au | |

| Palliative Care Outcomes Collaboration (PCOC): https://ahsri.uow.edu.au/pcoc/index.html | |

| Royal Australasian College of Physicians: https://www.racp.edu.au | |

| Japan | |

| Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research: http://ganjoho.jp/en | |

| Japanese Society for Palliative Medicine: https://jspm.ne.jp/elnec/elnec about.html. | |

| Japanese Society for Pharmaceutical Palliative Care and Sciences: http://jpps.umin.jp/en | |

| National Cancer Center Japan: https://www.ncc.go.jp/en/about/organization/index.html | |

| Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.html | |

| Japanese Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer: http://www.jortc.jp/index_EN.html. | |

| Japan Supportive Palliative and Psychosocial Oncology Group: http://www.j-support.org. | |

| Hospice Palliative Care Japan. Available from: https://www.hpcj.org/english/activities.html | |

| India | |

| Indian Association of Palliative Care http://palliativecare.in | |

| Institute of Palliative Medicine: https://www.instituteofpalliativemedicine.org | |

| Medical council of India Postgraduate medical education Regulations: http://www.mciindia.org/rules.and.regulation/Postgraduate-Medical-Education-Regulations-2000.pdf, page 37/ | |

| Pain and Palliative Care Society: http://www.painandpalliativecarethrissur.org/ | |

| Indian Health Data: http://www.healthdata.org/india | |

| Neighborhood Network in Palliative Care (NNPC): https://healthmarketinnovations.org/program/neighborhood-network-palliative-care | |

| Jordan | |

| Ministry of Health: http://www.moh.gov.jo/ | |

| AlMalath Foundation for Humanistic Care: http://www. facebook.com/AlMalathFoundationForHumanisticCare | |

| King Hossein Foundation & Center: http://www.khcc. jo/ | |

| Jordan Palliative Care & Pain Society: http://www.jopcs.org | |

| Jordanian Nursing & Midwifery Council: http://jnc.gov.jo | |

| The University of Jordan: http://ju.edu.jo/home.aspx | |

| Iran | |

| Ministry of Health and Medical Education: http://www.behdasht.gov.ir/ | |

| National Cancer Network: http://cancernetwork.ir/ | |

| Cancer Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences: https://crc.sbmu.ac.ir/ | |

| Iranian Cancer Association: http://www.ica.org.ir/ | |

| ALA Cancer Prevention and Control Center: http://macsa.ir/fa | |

| Others | |

| World Health Organization (WHO): www.who.int | |

| The reviewed hospice centers in each country | England |

| Saint Catherine Hospice | |

| Saint Christopher Hospice | |

| St. Richards Hospice | |

| Australia | |

| Hopewell Hospice | |

| Sacred Heart Health Service | |

| ST Vincent’s Hospital Sydney | |

| India | |

| Gana Prem Hospice | |

| Indian hospice in Jerusalem | |

| Ansaris Hospice | |

| Iran | |

| Alla Cancer Prevention and Control Center (Tehran City) | |

| Alla Cancer Prevention and Control Center (Isfahan City) | |

| Canada | |

| Stedman Hospice Service | |

| The Hospice of Windsor and Essex County | |

| Joseph’s Hospice | |

| Japan | |

| Garashi hospice | |

| St. Marys hospice | |

| Seirei Mikatahara Hospice service | |

| Jordan | |

| King Hossein Cancer Foundation & Center | |

| Al-Malath Foundation for Humanistic Care | |

| Istishari Hospital | |

| Basheer Hospital |

4. Results

In the current study, the HPC delivery systems in Iran and the selected countries (the UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, India, and Jordan) were assessed and compared in 6 axes based on WHO guidelines. PC delivery with a comprehensive approach in various settings requires effort and attention to different aspects such as policy-making, funding, service delivery, human resources development, access to medicine, and research. In this regard, each of the mentioned aspects was first described in the selected countries (Table 2) and, then, the differences and similarities among them were examined (Table 3).

| Axis (Fields) | Level | Activity | Country | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | Canada | Australia | Japan | India | Jordan | Iran | |||

| Policy-making | Preliminary | Form a palliative care working group with the support of government and senior specialists | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Analyze the situation of palliative care, including services, demographic needs, and legal barriers | * | * | * | * | * | - | - | ||

| Establish public education campaigns on palliative care and pain | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Initiate plan development/national strategy of palliative care | * | * | * | - | - | * | - | ||

| Intermediate | Develop a national palliative care program based on community inputs and the stakeholders of different sectors | * | - | * | - | - | - | * | |

| A full evaluation of population situation | * | - | * | - | - | - | - | ||

| Advanced | Develop the standards and protocols of palliative services in different areas | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | |

| Integrate palliative care into all policies and programs related to non-communicable diseases, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and child health | * | * | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Integrate palliative care in all levels of the health system | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Financial resources | Preliminary | Allocate the costs of palliative care from the national health budget | * | * | * | * | - | - | - |

| Intermediate | Include palliative care services in public health insurance packages | * | * | * | * | - | * | * | |

| Advanced | Provide free palliative care services to all eligible patients and social support for caregivers (leave and temporary care) | * | * | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Service delivery | Preliminary | Initiate palliative care in a certain community (providing palliative care services for patients with cancer both at home and cancer centers) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Identify patients with life-threatening conditions at different levels of care | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Intermediate | Establish referral and coordination mechanisms to develop palliative care networks in certain regions and communities | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | |

| Identify patients with life-threatening conditions at different levels of care | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Create palliative care services at a reference or regional hospital and support them with home care teams | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Develop palliative care services at all cancer centers and large public hospitals | * | - | - | * | - | - | - | ||

| Teach first level of service provision to adopt a palliative approach | * | * | * | - | - | - | - | ||

| Establish a child palliative system | * | * | * | * | - | * | * | ||

| Advanced | Expand the coverage of palliative care at home and in hospitals and all regions | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Expand home care services in all areas and for patients with cancer and other diseases | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Strengthen palliative care providers through integrating it into different levels of care | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Provide palliative services in areas that less attention has been paid to them, such as long-term care facilities for aged people and prisoners | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Human resource development | Preliminary | Train clinical managers by TOT method at home or abroad, if possible | * | * | * | * | - | * | * |

| Use palliative care educational modules for Health professionals, social workers, and volunteers providing the services | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Intermediate | Offer fellowship and nursing courses for specialists in the field of palliative care and pain control | * | * | * | * | - | * | * | |

| Establish a reference training center to provide palliative care training for physicians and nurses | * | - | - | * | - | * | - | ||

| Integrate palliative care topics into the educational curriculum of the nurses and physicians | * | - | * | * | - | * | - | ||

| Train physicians and nurses of the community in evaluating and managing pain and other symptoms | * | * | * | * | * | * | - | ||

| Train pharmacologists and other prescribers in the safe use of morphine | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Advanced | Establish specialized and super-specialized palliative care courses for physicians and nurses | * | - | * | * | - | - | - | |

| Establish palliative seats in palliative care universities | * | - | - | * | - | - | - | ||

| Availability of drugs | Preliminary | Examine legal/regulatory barriers of adequate access to controlled medicines | * | * | * | * | * | - | - |

| Examine the common use and access to essential drugs | * | * | * | * | * | * | - | ||

| Prepare a list of palliative care drugs in compliance with the WHO guidelines | * | * | * | * | * | - | - | ||

| Train and empower physicians providing palliative care for the safe use of Morphine in hospitals, regions, and selected communities, which are the starting place of these kinds of services. | * | * | * | * | * | * | - | ||

| Discussion and communication between legislators of drug and health sector and legislators and specialists in palliative care system regarding access to controlled medicines | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Intermediate | Reform governing rules and regulations for easy access to opiates to relieve pain following international drug conventions | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | |

| Estimate the need of population to essential palliative care medicines | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Examine the supply and distribution system of controlled drugs | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Ensure access to oral morphine in all regions | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Gradual reduction of costs and barriers to prescription and supply chain of narcotic drugs | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Advanced | Ensure fair access to analgesic drugs based on their needs, regardless of age, diagnosis, socioeconomic status, or geographical area. | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Ensure the reliable supply of palliative care medications to meet the needs of all regions of the country | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| Information and Research | Preliminary | Create a basic information system for monitoring and evaluating different levels of care | * | * | * | * | - | - | - |

| Create a general understanding of palliative care | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Intermediate | Establish a higher education center to conduct interdisciplinary research | * | * | * | * | - | * | - | |

| Control the quality of services | * | * | * | * | - | - | - | ||

| Advanced | Measure access to palliative services based on diagnosis and social group | * | * | - | * | - | - | - | |

| Create palliative care doctoral programs | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

Abbreviations: TOT, Training of Trainers; UK, United Kingdom; WHO, World Health Organization

| Item | Country | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | Canada | Australia | Japan | India | Jordan | Iran | |

| Policy-making | The development of a national hospice care strategy | Formulating End-of-Life care strategy and hospice palliative services at state and regional levels | Lack of a national hospice care strategy | Lack of a national hospice care strategy | Lack of a national hospice care strategy | Lack of a national hospice care strategy | Lack of a national hospice care strategy |

| Integrating the health services delivery system in the health system | Integration of hospice palliative services in the health system | Integration of hospice palliative services in the health system | Integration of hospice palliative services in the health system | Unclearness of the link between different sectors providing care service | Unclearness of the link between different sectors providing care service | Unclearness of the link between different sectors providing care service | |

| The development of general awareness programs | The development of public awareness programs | The development of public awareness programs | The development of public awareness programs | Non-integration of hospice care delivery system in the health system | Non-integration of hospice care delivery system in the health system | Non-integration of hospice care delivery system in the health system | |

| Running a public awareness campaign for hospice palliative care | The development of public awareness programs at a very limited level | Limited public awareness programs with a growing trend in recent years | |||||

| Financial resources | Free services | Free services | Free services | Free services | Free services | The services are not free on all occasions (only services provided by charities are free) | |

| To supply part of the financial resources, even in private sector, is upon government (subsidy allocation) | To supply part of the financial resources, even in private sector, is upon government (subsidy allocation) | In community-based services, the responsivity of supplying part of financial resources lies with the state and regional governments, and the other part is upon the insurance organizations and through the Medicare insurance coverage. The central government plays no role in providing resources. | The responsibility of financing hospice care services is primarily upon two insurance organizations, including National Health Insurance and Long-Term Care Insurance. Part of the funds in this regard will be paid by the patient, especially in the home-based services sector. | The main responsibility for financing it lies with the central government and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. | In the public sector, the government provides the cost of treatment and care for patients with cancer (mainly focused on acute care and treatment). | Financing services only in the public sector (mainly focused on acute care and treatment). | |

| To include hospice palliative care services in public health insurance packages | To include hospice palliative care services in public health insurance packages | Medical insurance does not play a major role in providing these types of services. | A major part of the service is provided by two private centers of King Hossein and Al-Muthalath. | Development of palliative care packages for patients with CVA, ICU, CHF, and cancer | |||

| Service delivery | To provide services for a wide range of diseases with an emphasis on cancer | To provide services for a wide range of diseases with an emphasis on cancer | To provide services for a wide range of diseases with an emphasis on cancer | Providing services to patients with cancer and HIV/AIDS | The services are provided just for patients with cancer | The services are provided just for patients with cancer | Only the patients with cancer receive general palliative services |

| Expanding services at all levels and care areas (hospital, home, and community) | Expanding services at all levels and care areas (hospital, home, and community) | Expanding services at all levels and care areas (hospital, home, and community) | Expanding services at all levels and care areas (hospital, home, and community) | The services are hospital-based and are provided across the community | The services are hospital-based and are provided across the community | Lack of formal structures for the provision of hospice palliative care | |

| Mainly toward providing home-based services | Mainly towards providing home-based services | The emphasis is more on inpatient hospital services | The emphasis is more on care in hospital settings | Mainly toward home-based services | Has a palliative care unit at Firoozgar Hospital and some general palliative care services provided by home care centers. | ||

| Provision of services primarily at the primary level and by GP or regional nurse area | Provision of care based on state-level standard care model | Providing services mainly at primary level and by family physicians | Lack of a certain care model | Lack of a certain care model | The emphasis is more on care in hospital and hospice facilities | Lack of a certain care model | |

| Provision of care based on a national standard care model | Provision of a wide range of services | Provision of care based on national-level standard care model | The services are more limited compared to other surveyed countries | The services are more limited compared to other surveyed countries | Lack of a certain care model | A very limited range of services and institutions Unclearness of the link between service providing sectors | |

| Provision of a wide range of services (the most complete type) | Presence of coordination and communication between different service providers at the national and regional levels | Provision of a wide range of services | Unclearness of the link between service providing sectors | Unclearness of the link between service providing sectors | The services are more limited compared to other surveyed countries | ||

| Presence of coordination and communication between different service providers at the national level | Formation of the Silver Chain Group hospice Palliative Services for coordination and communication between different service providers. | N/A | Unclearness of the link between service providing sectors | ||||

| Human resource development | The use of volunteers | The use of volunteers | The use of volunteers | The use of volunteers | The use of volunteers | N/A | Nonuse of volunteers |

| Presence of a wide range of specialists in the team formation (the most complete type) | Presence of a wide range of specialists in the team formation (more limited in compared with the UK) | Presence of a wide range of specialists in the team formation (more limited compared with UK) | The formation of the specialized team is more limited compared with other surveyed countries | The formation of the specialized team is very limited | The use of team formation and more specialists, despite more limited service providing centers | The formation of a specialized team is limited | |

| Development of training and creation of specialized disciplines in different levels | Development of training mostly in the nursing area (more limited in compared with the UK) | Development of training and establishment of specialized disciplines at different levels with more emphasis on nursing and medicine | Development of training and establishment of specialized disciplines at different levels with more emphasis on nursing and medicine | Extremely limited training programs for the specialists | Development of training and establishment of specialized disciplines at different levels with more emphasis on nursing and medicine | ||

| Drug availability | Developing national guidelines and access to opioid and narcotic drugs | Developing state guidelines and access to opioid and narcotic drugs | Formulating a national guideline and access to opioid and narcotic drugs | -Limitation in having access to opioid and narcotic drugs | Lack of a national or state guideline regarding access to opioid and narcotic drugs and limited access to the drugs | Lack of a national or state guideline regarding access to opioid and narcotic drugs and limited access to the drugs | Lack of a guideline regarding access to opioid and narcotic drugs |

| Information and research | Development of NEoLCIN the with a capability to access to all sectors involved in the provision of hospice services and the dissemination of information related to it as the MDS | Establishing links between state and regional hospice centers, hospitals, and the various sectors providing hospice services through creating related dataset by Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) and the Institute for Clinical Evaluation Sciences (ICES) | Research development at a national level | Research development at a national level | N/A | Limited research | Growing research in recent years |

| Development of the research and specialized tools required for the EOL care services in the UK by the Sue Ryder Institute and at a national level | Validating programs (auditing, evaluation) is carried out by the Accreditation Canada Agency and in terms of system performance, risk prevention planning, client safety and governance. | Formulate, develop, and examine quality control indices | Formulate, develop, and examine quality control indices | N/A | N/A | ||

| Validate and evaluate the performance of the institutes and centers providing Hospice Palliative Services through the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence NICE (NICE) | Formulate and develop numerous end-of-life care research projects at the state and regional levels | ||||||

Abbreviations: EOL, End-of-Life; GP, General Practitioner; MDS, Minimum Data Set; NEoLCIN, National End-of-Life Care Information Network; UK, United Kingdom (UK)

4.1. Policy-Making

Two major activities in this axis include developing a national PC plan and integrating it into all policies and programs, as well as all levels of the health system. HPC in some health systems is an independent plan or a part of a national health program or a component of a cancer control program (the National EOL Care Program in England (18). In Canada and Australia with a decentralized health system, it was provided in the different regions based on various plans at the state and territorial levels. Although efforts have been made in this area since 2002, they have not led to the development of a national HPC plan and the provision services based on it (19, 20). Other surveyed countries did not formulate a national program despite the provision of HPC services in various settings (6, 21-24).

Also, the UK, Canada, Australia, and Japan have merged HPC services into different levels of the health system. They are mainly provided by General Practitioners (GPs) at PHC (18-21). There was no evidence for Jordan and India. In Iran, the first policy-making was on PC in the adult with cancer, which led to the design of the National Comprehensive Palliative and Supportive Cancer Care Program in 2012. Iran lacks any formal structure and program for the provision of HPC services. Of course, in recent years, a few centers offer scattered PC services to patients with life-limiting illnesses (especially cancer patients), which are in hospital wards and home and they are mainly provided in large cities. It may include EOL care, too. These have been provided without referring to the clinical guidelines and solely based on the knowledge and experience of the care providers (25-27).

4.2. Financial Resources

HPC services mainly fund through government subsidies or to assign a part from health budget (the UK and Canada) (19, 28, 29), national insurance schemes, and including them into public health insurance packages (Australia and Japan) (30, 31) or charity funds (32, 33). In Iran, few charity institutions (e.g. Alla Institute) provide some free-of-charge PC services to patients with cancer, who may be at EOL. Also, private home care centers provide general care services, which may include HPC, but these services are not free and they mainly include physical care. Although there are many charity associations in the country, which provide general care to patients with cancer, each one of them merely operates in one dimension and does not offer comprehensive services.

4.3. Service Provision

In the UK and Canada, services are available for a wide range of diseases and are extended into different settings. However, they predominantly are provided at the PHC level by GPs or the District Nurses (DNs) and mostly at home and based on the national standard care model. Besides, various service providers are linked and coordinated across the country (29, 34). In contrast, in Australia, inpatient HPC services are mainly emphasized. The Silver Chain Group is formed to facilitate coordination and connection among different sectors (35). In Japan, they are mostly offered in hospitals, and just to cancer and HIV/AIDS patients without using a national standard model and clear relationship among sectors (31, 36). The results for India (32) and Jordan (23, 33) are presented in Tables 2 and 3. In Iran, despite the stratification of health services, the patients are still referred by oncologists to a few centers to receive general PC services. Also, the special HPC program is not planned for EOL patients. There is not a clear linkage among these centers (27).

4.4. Human Resource Development

A wide range of activities such as holding various training courses, integrating the related topics in the curriculum of various health care disciplines, building specialty or subspecialty qualifications, implementing registered nurses prescribing plan, holding virtual and electronic training courses for all health professionals, and educating volunteers have been carried out in the UK (37). In Canada, HPC is mainly provided by Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and training programs have mostly focused on nurses. Physicians who are interested in PC will permit after a one-year training course (29). In Australia and Japan, the nurses can continue their education in the MSc of HPC (38). But in India, the trained staff shortage is a major barrier (39). In Jordan, 2 HPC service centers take advantage of specialists trained in other countries (40). In Iran, inadequate training and the lack of knowledge and experienced workforce in PC is one of the major challenges ahead (10, 25, 41-43).

4.5. Availability of Medicine

The UK (44), Canada (45), and Australia (46) developed national guidelines and protocols and created unlimited free access to sedative and narcotic drugs on HPC providing. Also, they designated processes for access to morphine and data registration of opioids consumption. Besides, they held training courses and workshops on opioids prescriptions and the relevant laws and regulations. In Iran, the MOH has developed a pain control protocol for patients with cancer, based on which the Food and Drug Administration affiliated to each university of medical sciences is responsible to meet the opioid needs in the centers that are under their supervision and provide PC services. The Narcotic and Controlled Drugs Office of Food and Drug Administration records patients’ requests. The patients who have used opioids for more than 1 year should be examined by a medical committee. If their need for opioids is confirmed, their prescription will be renewed for 1 month (47).

4.6. Information and Research

Only the UK (48) and Canada (49) have established the National End-of-Life Care Information Network (MDS) to access related data on HPC services. Other proceedings with aim of delivering high-quality services include research development, building specialized research tools and services, and the performance evaluation and accreditation of centers through national and international institutions (19, 38, 50-52). In Iran, the information registration system is introduced as a major challenge. In return, the existence of Cancer Research Centers with a priority on PC research, palliative care sections in cancer journals, holding congresses on PC, presenting scientific articles, and writing academic dissertations in the PC domain among the others are the strengths (47, 53).

In terms of creating public perception and awareness about HPC, the establishment of public education campaigns and the implementation of general awareness raising programs are examples in the studied countries (19, 38, 50-52). In Iran, public educational plans have not been implemented yet. The other findings are presented in detail in Tables 2 and 3.

5. Discussion

As governments attempt to improve the lives of their citizens throughout the world, they must also pay attention to the quality of their deaths (16). In Iran, the demand for EOL care is increasing considering the population aging and increased chronic disease statistics such as diabetes, cancer, and heart diseases combined with advances in the field of care and treatment (10). The international comparison of HPC systems determines the similarities and differences among them and identifies factors that may affect developing policies throughout the country. In the present study, the HPC delivery systems in Iran and the mentioned countries were reviewed and compared according to the WHO guideline.

In the policy-making axis, it is crucial to develop a national PC program and integrating it into all national policies and plans, as well as at all levels of the health system, (17). According to the results of the study and in line with EIU's report, making national policies to increase access to PC services is essential. Successful countries have a comprehensive and purposeful policy-making framework and have integrated HPC services into different levels of their health systems (16). This integration will lead to enhanced availability and improved outcomes (17, 54). The results of recent research on PC also showed a need for HPC services in Iran, but since PC is an emerging approach, the HPC system establishment needs further research and preparation of facilities and requirements (10, 14, 41, 42, 53). However, from the experts’ point of view, the implementation of the above actions will face limitations given that the PC system of Iran is still in its infancy. It seems that integrating these services into the health system of Iran requires widespread policy-making in the field of health care more than anything (43, 55).

On the other hand, without financial support, EOL patients cannot have access to the HPC. Although a fiscal investment, it can lead to savings in health care costs (28). In this regard, developed countries have different approaches such as the allocation of major subsidies to HPC programs, the assignment of significant funds of the health budget to HPC services, the utilization of national insurance and pension schemes, and donation (16). In Iran, the lack of insurance coverage regarding home care services is a challenge (56). Of course, the MOH designates service packages that cover home care services (for patients with cancer, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), congestive heart failure (CHF), and the patients requiring ICU care) in recent years.

Although still not implemented, MOH signed a memorandum with some charitable organizations such as “Ala Institute” to establish the inpatient unit and daily clinic and the formation of home care teams to provide PC services to patients with cancer (57).

Based on the results, hospice services are offered in a wide range of diseases with an emphasis on cancer. Also, services are extended to all levels and settings of care (hospital, home, and community). In this regard, it has been stated in various sources that hospice services can be offered in various models, including hospice home care service, inpatient hospice service, and hospice day care service. It is particularly important to provide a variety of care settings for easy access to services (17). Besides, based on the experiences of many countries, providing services in the appropriate and different settings based on patient and family needs is an important principle in the design of the palliative care system (58). On the other hand, dying patients have complex and ever-changing needs that can rarely be met through one type of service, facility, or in one setting and, thus, require diverse services in a variety of health care settings (59, 60).

Also, training health professionals about PC is essential to meet the growing demands of EOL patients (17). In Iran, the following educational challenges are addressed in recent studies as barriers to the development of PC: the lack of a regular education program and standard content about PC in the curriculum of different disciplines, insufficient knowledge of the workforce, students, and other health workers on basic principles of PC, expert trainers shortage, limited studies regarding educational needs of PC provider, limited scientific conferences and rounds held with the attendance of various professionals (27, 61), the weakness of interdisciplinary team management, and nurse, social activists, psychologists, and other experts shortage to providing PC (62). However, the presence of nursing and medical students and other specialized disciplines, the existence of specialized research centers in the medical universities and health centers, prioritizing to training programs on PC by health managers, emphasizing the MOH authorities on establishment of the PC program, the existence of several scientific associations and journals on cancer, access to international PC models such as WHO guideline, the availability of non-governmental organizations to support educational programs on PC, access to IT systems to hold virtual educational sessions, appropriate infrastructure, and the educational potential capacity of colleges and universities are the strengths and opportunities that can facilitate the development of HPC services in Iran (27, 43, 61, 62).

Moreover, the quality of care depends on the availability of opioids. In many countries, access to opioids is challenging. Many legal constraints, the lack of awareness, and fear of social stigma are barriers to accessing narcotics (15). In Iran, it has also been noted that narcotics utilization to pain control is low and is attributed to the absence of different types of opioids, very limited access to them, restrictive laws and regulations regarding its prescription, insufficient knowledge of most physicians and almost all patients with administrative processes of opioids prescription and preparation, and, in some cases, the negative attitude of physicians, patients, and their families toward using them. Besides, available drugs are not prescribed in the same way and sometimes have been abused (63). Also, based on the studies, most health care providers did not have sufficient knowledge and a positive attitude to use opioids to reduce pain in patients with cancer. In other words, despite access to the pain measurement tools and guidelines and availability of pain killers, due to the inadequacy of knowledge and negative attitudes, the pain in patients with cancer is not adequately controlled and they endure the pain until the end of their lives (57, 64, 65). Therefore, training specialists and therapists is a necessity.

On the other hand, one of the essential principles for developing research is the availability of basic information that requires the establishment of a national integrated data registration system. It helps in assessing and monitoring HPC on different levels, quality control, and measuring the individuals’ access to them (20).

One of the major goals of research on PC is continuous enhancement and quality of care improvement. The ultimate goal is evaluating the quality and improving the program’s results. In other words, improving the quality of health services both indicates the program defects and can help problem solve. As a result, one of the most important prerequisites for achieving this important goal is to conduct research (57, 66).

Another important considering issue is creating perception and raising public awareness regarding HPC. Attempts at the community should be in the direction to raise public awareness and to encourage conversations about death (19). In Iran, the lack of general education programs on PC can be attributed to the small number of PC provider centers, limited facilities and resources, and the lack of formal structures for HPC delivery. Based on previous studies, the lack of knowledge and information on HPC, the cultural context, and religious beliefs of the patient and their families are mentioned as barriers to developing it. In this regard, it is suggested that the barriers be eliminated through improving general awareness and participating patients and their families in program planning (17, 29).

5.1. Conclusions

The present study shows that Iran lacks any formal structure and program for HPC delivery services. Iran lacks any formal structure and program for the provision of HPC services. Of course, in recent years, a few centers offer scattered PC services to patients with life-limiting illnesses (especially patients with cancer), who are in hospital wards and home and they are mainly provided in large cities. It may include EOL care, too. These have been provided without referring to the clinical guidelines and solely based on the knowledge and experience of the care providers.

Findings based on the WHO guideline addressed the following essential activities to develop an HPC delivery system: developing a national plan for delivering HPC services and, as far as possible, integrating it into all levels of the health system, reforming laws and regulations for faster access to opioids and training specialists on how to prescribe them, developing HPC services in PHC and community level, providing financial resources, training workforce, establishing national information networks, and increasing public awareness. This study is one of the few studies that has analyzed the HPC delivery systems of some countries through WHO guideline and it is applicable for designing and developing HPC systems.