1. Context

Pain is a common symptom associated with cancer and its treatment. Studies have reported that approximately 75% – 90% of patients with cancer experience pain during the course of illness. Pain management is one of the major challenges that need intervention in patients suffering from cancer (1).

Pharmacological support is the most common modality to cope with chronic and unbearable cancer pain. In addition, complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) are increasingly used as adjunct therapy alongside pharmacological and conventional treatments. The complementary therapies include massage, aromatherapy reflexology, relaxation therapy, hypnotherapy, and acupressure (2). Research has reported the use of CAM among patients with cancer between 7% to 64%.(3-7).

Among the CAM modalities, reflexology is one of the oldest and most popular palliative interventions which is easy to learn and perform and has no associated side effects so far. This method is increasingly popular in cancer palliation; a recent US survey of 4,139 cancer survivors suggested that 11.2% of them used one type of massage therapy (8). Reflexology is defined as a method of manipulating the soft tissue of whole body areas using pressure and traction by hands or mechanical devices. Massage brings about a range of psychological and physiological changes including an improvement in blood and lymph flow, reduction in muscle tension, an increase in pain threshold, improvement in mood and mental state, reduction of blood pressure, and relaxation of the mind (9).

Evidence in support of massage for treating patients with cancer pain remains inconclusive. A few meta-analyses evaluating the effects of foot reflexology on cancer pain have been conducted; the present article is an attempt to update those.

2. Objectives

The objective of this systematic review was to accumulate and analyze the evidence from interventional studies on reflexology as an adjunct therapy in relieving cancer pain.

3. Data Sources

The electronic databases of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, and PubMed were searched until 2018 using the keywords ‘reflexology’, ‘massage therapy’, ‘zone therapy’, ‘complementary therapy’, ‘cancer’, ‘neoplasm’, and ‘Carcinoma’ (see details in appendix 1 in supplementary file). All references of the systematic review articles obtained from the search results were reviewed by two authors (ZN, KS).

4. Study Selection

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-equivalent control groups or quasi-experimental and before-after studies that focused on pain management by reflexology modality as an intervention in patients with cancer regardless of cancer type.

The search results obtained from the selected databases were entered into the endnote software, duplicate studies were excluded, then the titles and abstracts were examined and irrelevant articles were removed based on inclusion criteria. Finally, the full texts of remained papers were reviewed for inclusion into the meta-analysis. Two authors (ZN, KS) performed all of the above steps individually.

5. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A datasheet was used to extract data. The extracted information included name of authors, year of publication, study location, type of study, sample size, and outcome indicator. Consensus was reached by discussion with a third author in case of disagreement during each stage of selection, qualitative assessment, and extraction of data. The effect of reflexology for patients with cancer pain (treatment vs. usual care) was investigated as the main outcome.

Two authors (ZN, KS) conducted risk assessment of all the articles based on the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (10). The risk of bias for each item was rated as “low risk”, “high risk” and “unclear” bias.

5.1. Data Synthesis and Analysis

The analysis was done based on Morris’ study (11) who reported using an effect size based on the pooled pretest standard deviation (SD) compared with pooling SDs across both pretest and posttest scores, and also the pretest SD in the treatment and control groups is the best choice because it provides an unbiased estimate of the population effect size and has a known sampling variance. The standardized mean difference between the intervention and control groups was calculated for each study, based on the mean and pooled pretest SD, and the sample size in control and intervention groups. We pooled data across studies using a random-effect model. According to Cohen (12), effect size d = 0.80 and above was interpreted as a ‘large-sized effect’, 0.51 - 0.80 was considered as a ‘medium-sized effect’, and 0.2 - 0.5 was described as a ‘small-sized effect’. The publication bias was explored by the funnel plot and heterogeneity was measured by the I2 statistic. Results were expressed as mean difference with 95% confidence intervals (CI); P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Since included studies came from different settings, we performed a random effect model (13). Data were analyzed using the Revman software.

6. Results

6.1. Selection of Eligible Studies

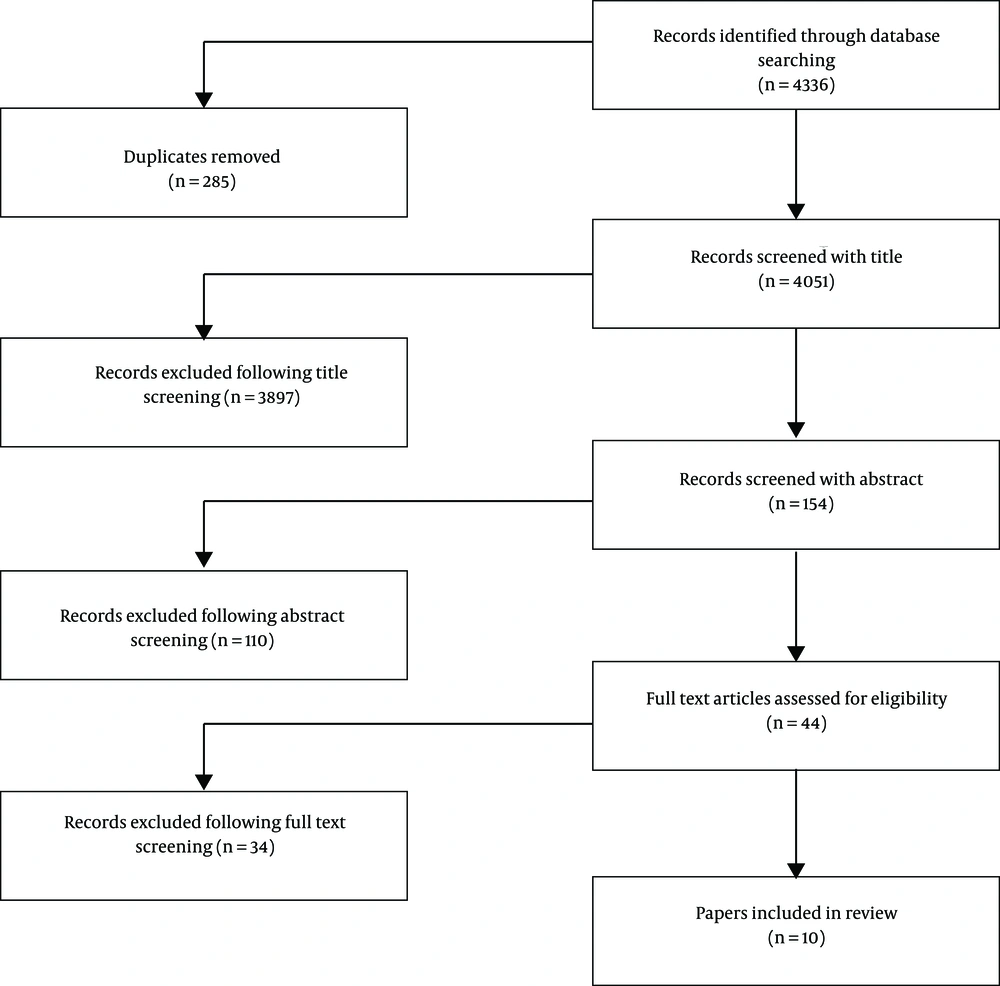

We identified 4051 studies as potentially relevant. After screening the titles and abstracts 3968 studies were excluded and 44 studies and 27 systematic review articles in complementary medicine scope were fully evaluated. Finally, 10 articles were included that 8 articles (9, 14-20) -published from 1998 to 2018- were entered into the meta-analysis and other articles were reported narratively because of the defect in data (21, 22). The analyzed articles consisted of five randomized clinical trials, one quasi-experimental research, and two pre-post design studies. Data related to subjects, duration, frequency, and time per session for foot reflexology were extracted. The selection of eligible studies was conducted based on the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

6.2. Quality Assessment

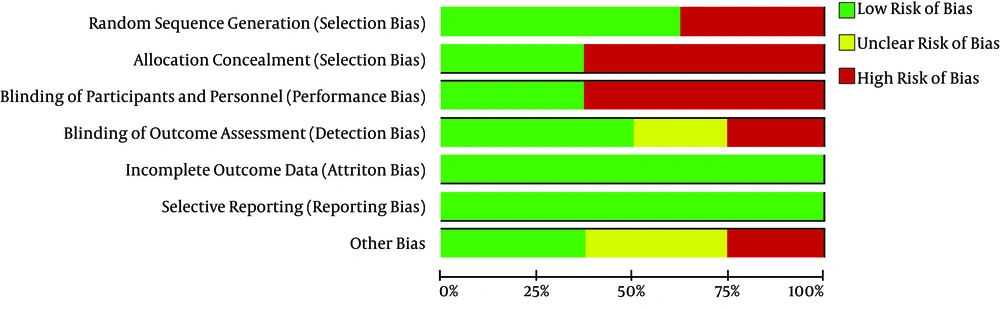

Between included studies, two studies were high-risk in randomization, three studies have preventive action for contamination bias, four articles have blinding in data gathering and one article was high-risk in basic characteristics and outcome measures (Figure 2).

6.3. Characteristics of Eligible Studies

Included studies were originated from the USA, Italy, Taiwan, Egypt, and Iran. Reflexology sessions typically lasted one to eight sessions and the minimum length of each session was 30 minutes. Intervention was done by reflexologists, trained staff, and nurses. Pain was assessed with visual analogue scales (VASs), the Brief Pain Inventory, Anderson Symptom Inventory, and PROMIS, but the most commonly used measurement tool was the VAS score (4 articles).

In this systematic review, eight articles had been included in the meta-analysis that had used reflexology as an intervention in cancer pain management (9, 14-20). Studies involved 30 - 256 participants with different cancer diagnoses (three studies had more than 100 participants). The average age of patients was 53.4 years in intervention and 52.3 in control group and most of the participants were female.

6.4. Meta-Analysis of Reflexology on Pain

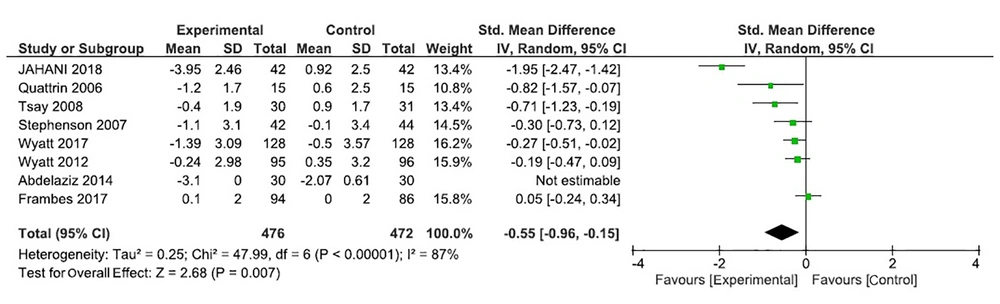

The effect of reflexology in patients with cancer pain compared with usual care or placebo reflexology was significantly based on a random- effects model meta-analysis of data in eight articles (standardized mean difference (SMD) = -0.55 [95% CI = -0.96 to -0.15]). In sum, accumulated results of studies showed that reflexology has a large effect on cancer pain (see forest plot in Figure 3). Significant results in favour of the intervention with positive effects were reported in six articles (14, 16-20).

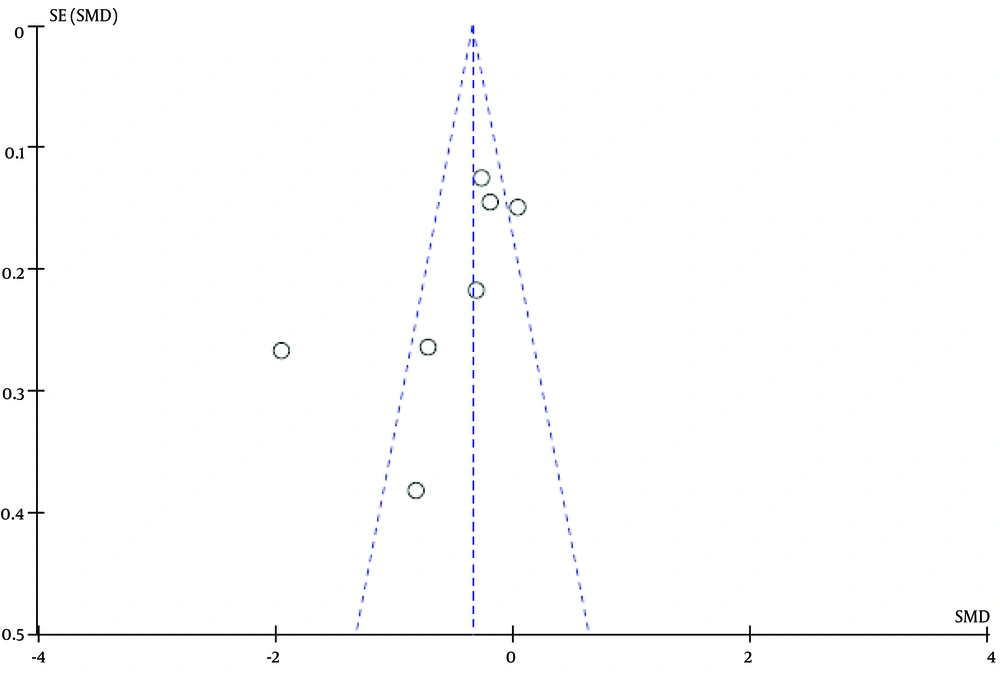

The results of the Egger’s tests indicated evidence of publication bias among the studies (P < 0.05). The funnel plot confirmed these findings (Figure 4). Heterogeneity was measured by the I2 statistic. The results showed a heterogeneity (I2 = 87 %, P < 0.001), however, we used the random-effect model.

None of the included studies reported any adverse effects associated with reflexology. We found a qualitative study reporting that healing crisis may be experienced after reflexology sessions. Followed by reflexology intervention, the participants reported symptoms with different severity including a mixture of pain, fatigue, and flu like symptoms along with a variety of some other signs and it gradually became worse until the abrupt diminishing of symptoms around the seventh and eighth sessions of the intervention (23).Overall, reflexology can be considered as a safe procedure since it does not require any drugs or invasive intervention.

7. Discussion

The combined effect sizes and the 95% confidence intervals could be a proof of the effectiveness of reflexology in alleviating cancer pain. The current study has marked that reflexology effectively relieves cancer pain in all types of cancers included in the study.

Two systematic reviews with meta-analysis by Lee SH et al. (24) and Lee J et al. (25) have previously assessed the effect of reflexology in patients with cancer. The present study was an attempt to update those. Based on the last reviews, the evidence levels for the benefits of reflexology on cancer pain vary, Lee et al. indicated that massage is effective for the relief of cancer pain based on a meta-analysis of 4 studies specifically designed on the effect of reflexology (24) in diminishing pain in patients with cancer undergoing surgery. By conducting a meta-analysis, Lee et al. assessed the effect of reflexology, in general, and not specifically on cancer pain and indicated that foot reflexology is not a useful intervention to relieve pain (25). However, the combined effect sizes in this systematic review showed a considerable effect of foot reflexology on cancer pain. Reflexology diminished the level of pain in patients with cancer. In the current review, 5 out of 8 studies found significant positive effects in controlling cancer pain.

Also, the results of another systematic review without meta-analysis confirmed these findings. A review study by Ernst conducted on the effectiveness of reflexology for treating any medical condition for patients with diabetes, premenstrual syndrome, cancer, multiple sclerosis, symptomatic idiopathic detrusor or over-activity, and dementia suggested that reflexology had significant effects for patients with cancer pain. The review considered reflexology among massage therapy types (26). But, we performed a meta-analysis to investigate the only effect of reflexology in controlling pain in patients with cancer. Also, Wang’s review evaluated the efficacy of reflexology in any condition in which five studies were included. They reported there is no evidence for any specific effect of reflexology in any conditions (27). Rueda’s Review assessed the effect of reflexology in two articles that showed some beneficial, however short-lasting effects associated with reflexology (28). Myers et al. conducted a narrative review where they investigated five articles on reflexology and reported interventions ranged from a single 20-minute session of foot reflexology to six weekly sessions. Most of the articles have provided less details on reflexology protocols (29).It is clear that previous reviews have also had contradict in favor of reflexology as an effective intervention in cancer pain palliation.

Reflexology sessions typically lasted from a single 20-minute session of foot reflexology to six weekly sessions and were implemented by nursing students to certified reflexologists. Articles have offered details on reflexology protocols. The level of pain among patients was assessed using visual analogue scales (VASs), the Brief Pain Inventory, Anderson Symptom Inventory, and PROMIS. According to Russell et al., the massage therapist may influence treatment effects (30). Therefore, assessing the aforementioned information in articles is vital.

8. Conclusion

In summary, we implemented a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the effects of reflexology on pain relief in patients with cancer. We found sufficient evidence that reflexology has positive effects on diminishing pain among patients suffering from cancer and can be used as a treatment for alleviating cancer pain. But it should be considered that the number of studies included in the present research was small with different levels of quality. So, we recommend that further studies be performed with larger sample size, well-designed trials with sufficient duration and longer follow-up periods with clear details about reflex practitioners, duration of intervention, instrument for pain assessment, and outcome. Meanwhile, patients should be adequately monitored and adverse effects should be reported. All of the aforementioned issues might influence the impact of reflexology as an adjuvant treatment.

8.1. Limitation

First, there is a potential list of missed studies in the present meta-analysis, including those published in languages other than English and study data that are not published in conventional journals (i.e. theses). However, we overviewed all recent systematic reviews to ensure that no trial in the English language was missed. Second, we faced heterogeneity in the results and short term studies with small sample size or weakness in blinding and random assignment procedures that may be rigorously instituted having these in mind, the results should be interpreted with caution.