1. Context

As a characteristic feature of smokeless tobaccos, it is non-combustible. Other names for smokeless tobacco include chewing tobacco, oral tobacco, spit tobacco, and snuff. Nicotine and other chemical compounds are attracted via oral epithelium. The chemical composition of smokeless tobacco products is typed based on brands and manufacturers. Smokeless tobacco products contain nicotine and carcinogens. Minimum 28 carcinogens, containing nitrosamines (i.e., nicotine-derived nitrosamine ketone [NNK] and N'-nitrosonornicotine [NNN]), are found in smokeless tobacco products (1). Although most young people think that tobacco use is harmless (2), studies show that adolescents, who use smokeless tobacco products, are exposed to significant levels of nicotine and NNK (3). The clinical picture of oral lesions depends on the type, brand, dosage, and duration of tobacco use. Tobacco keratosis, gingival retractions, and epithelial dysplasia are seen in smokeless tobacco users. Oral, esophageal, and pancreatic cancers have been seen in smokeless tobacco users (4). Over the past 2 decades, due to oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) primarily asymptomatic nature, the 5-year survival rate of OSCC remains at about 50%, leading to advanced stages diagnosis with few therapeutic choices. Delayed patients or the lack of evaluation professionals may delay diagnosis (5, 6). The initial phase in treating cancer appears to be early detection, especially in high-risk individuals. The best way to detect cancer early is through screening (7).

Saliva is a non-invasive, fast-collecting, and cost-effective substance. It is a fluid rich in protein, enzymes, and minerals that has attracted the attention of researchers in recent years. Collecting saliva is easier and safer than collecting blood. Salivary biochemical parameters can be used to diagnose and evaluate some disorders, such as immune disorders, infectious diseases, cancers, and psychological disorders (8).

The main aim of this article is to review the available literature and to summarize the application of salivary markers in smokeless tobacco users, as well as to discuss their capacity as potential biomarkers for malignant transformation.

2. Evidence Acquisition

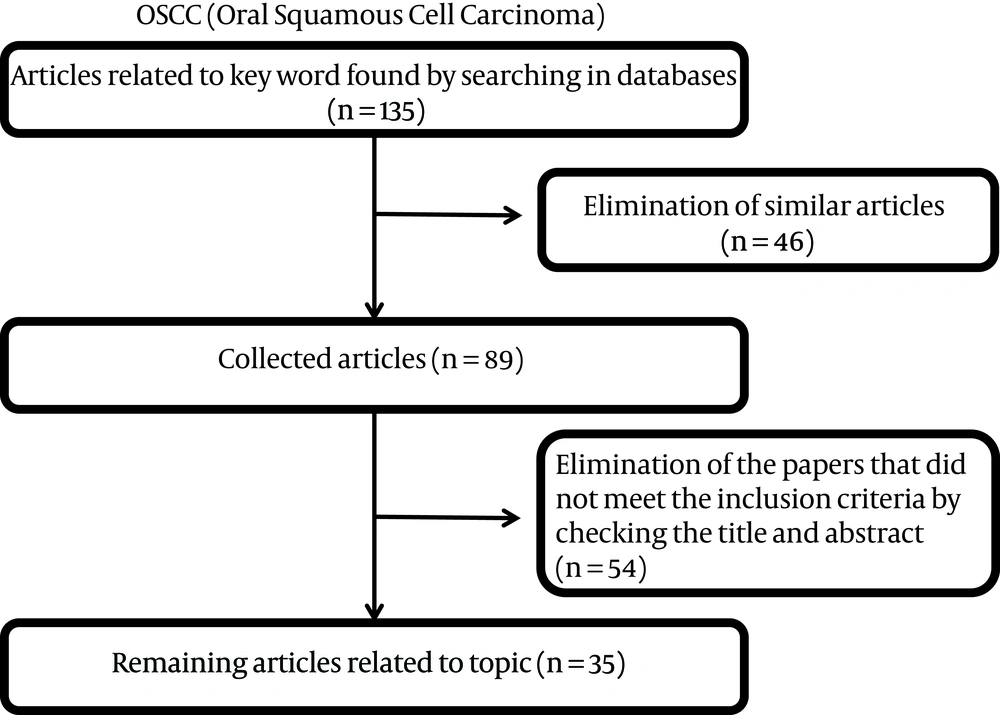

This paper was considered a review of salivary markers in smokeless tobacco users. The review included an electronic search in PubMed, MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and Google databases, using the terms “saliva or salivary”, “markers or biomarkers”, “smokeless tobacco or Chewing tobacco or snuff”, and “oral cancer or oral carcinoma or oral squamous cell carcinoma”. In this review, both the original and review types were considered. Salivary markers of smokeless tobacco were restricted to salivary markers related to OSCC. The articles were initially screened by title and abstract, followed by a full-text analysis. Then, the articles were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: original articles, published in the English language over the past 20 years (2000-2020), and studies with human subjects (Participants enrolled in the “case” group were diagnosed with OSCC or smokeless tobacco users, while “controls” were healthy individual). For all articles, the saliva marker had been measured (Figure 1).

3. Results

Our initial search identified 135 articles, 35 of which met final inclusion criteria and were included for review. In summary, these studies described 5 groups of markers found in the saliva of smokeless tobacco users linked to oral cancer. These salivary markers that are resulted from the electronic search are addressed below.

3.1. Cytokines

Many cells of the immune system secrete cytokines. Cytokines are divided into two groups, namely pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory. Interleukin 1 (IL-1), Interleukin 6 (IL-6), interferon (IFN)-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α are pro-inflammatory cytokines, and Interleukin 13 (IL-13), Interleukin 10 (IL-10), and Interleukin 4 (IL-4) are anti-inflammatory cytokines. Anti-inflammatory cytokines are responsible for reducing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines and stopping the immune response (9).

Javed et al. reported that salivary IL‐6 and Interleukin 1 beta (IL‐1β) levels were higher among gutka chewers than the control group (10). Also, in the study of Abbasi et al., Salivary Interleukin 1-beta levels were higher in smokeless tobacco consumers compared to controls (11).

In a study by Sohail et al., salivary interleukin 8 level was higher in smokeless tobacco users than in healthy people (12).

Sharma assessed salivary interleukin-6 (IL-6) in persons with leukoplakia and periodontitis, individuals with periodontitis but without leukoplakia, and healthy individuals. In the leukoplakia group, the IL-6 level was elevated with a rise in the score of dysplasia. They stated that a significant rise in salivary IL-6 occurs in tobacco users (13). Dineshkumar et al. reported that salivary IL-6 is elevated in people with OSCC compared to premalignant lesion and control groups (14).

Aziz et al. showed that the rate of salivary cytokines, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and IL-1RA (Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist) significantly increased in OSCC individuals, with the duration of smokeless tobacco use being related to the increase of salivary IL-1RA (anti-inflammatory cytokines) (15).

Some studies showed that serum and salivary TNF- α was increased in OSCC subjects compared to the healthy control and oral premalignant disease group. Patients in oral cancer and premalignant disease groups had a history of tobacco use (tobacco/pan chewing/smoking) (16-18). Lee et al. reported that salivary INFγ, TNF-α, IL-8, IL-6, and IL-1β were elevated in people with OSCC compared to control groups (Table 1) (19).

| Authors | Cytokines | Level in Patients with OSCC | Level in Smokeless Tobacco Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| Javed et al. (10) | IL‐6 and IL‐1β | Increase | |

| Abbasi et al. (11) | IL‐1β | Increase | |

| Sohail et al. (12) | IL‐8 | Increase | |

| Sharma et al. (13) | IL‐6 | Increase | |

| Dineshkumar et al. (14) | IL-6 | Increasea | |

| Aziz et al. (15) | IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and IL-1RA | Increasea | |

| Krishnan et al. (16) | TNF-α | Increasea | |

| Ameena et al. (18) | TNF-α | Increasea | |

| Lee et al. (19) | INFγ, TNF-α, IL‐8, IL‐6 and IL‐1β | Increasea |

Summary of Salivary Cytokines in Smokeless Tobacco Users and Patients with OSCC

3.2. Immunoglobulins

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is the most common antibody in the bloodstream, and although there is local production in the mouth, most IgG saliva is derived from serum. IgG defends against infection from pathogens such as viruses, toxins, and bacteria, and IgG in saliva may be a sign of oral inflammation (20).

Salivary immunoglobulin A levels inhibit microbial adherence, colonization, and penetration of the mucosal surfaces; it neutralizes viruses and toxins and inhibits the growth of certain organisms. Plasma cells secrete IgA. Decreased salivary IgA in tobacco users may be due to nicotine and its metabolites. Nicotine significantly reduces lactoferrin and salivary lysozyme and could be the reason for smokeless tobacco users having decreased IgA levels (21, 22).

Doni et al. compared salivary immunoglobulin A levels in tobacco users with healthy people. In this study, a decrease in immunoglobulin A levels was observed in tobacco users compared to the healthy group. Also in smokers, the reduction was greater than in tobacco chewers (23).

Alshehri et al. reported that salivary IgG levels were significantly higher among smokeless tobacco users than the controls (24). Some studies have shown an increase in salivary IgG levels and a decrease in salivary IgA among individuals with OSCC compared to the control group (Table 2) (25, 26).

| Authors | Immunoglobulins | Level in Patients with OSCC | Level in Smokeless Tobacco Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doni et al. (23) | IgA | Decrease | |

| Alshehri et al. (24) | IgG | Increase | |

| Shpitzer et al. (25) | IgG, IgA | Increase in salivary IgG The decrease in salivary IgA | |

| Abdullah et al (26) | IgG, IgA | Increase in salivary IgG The decrease in salivary IgA |

Summary of Salivary Immunoglobulins in Smokeless Tobacco Users and Patients with OSCC

3.3. Antioxidants and oxidants

Oxidative stress results from an imbalance among the production of free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the antioxidant defense system. Free radicals are involved in the process of carcinogenesis. The increased expression of proto-oncogenes, Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) base alterations, and destruction to tumor suppressor genes are induced by free radicals. In individuals with oral cancer, increased blood levels of lipid hydroperoxide, malondialdehyde (MDA), and decreased blood levels of antioxidants catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, vitamin C, and vitamin E have been seen (27).

Tobacco consumption has a direct correlation with DNA injury when a cell with DNA damage divides metabolism and duplication of cells becomes mutations, which is an important factor in carcinogenesis. ROS, free radicals, and reactive nitrogen species released during cigarette smoking and tobacco chewing initially will cause dysplastic lesions and, then, transform into carcinoma lesions (28).

Arbabi-kalati et al. reported that the use of tobacco products decreases the antioxidants activity of the saliva (29). A study by Begum et al. showed the reduced levels of antioxidant enzymes and the rise of the production of ROS in the saliva of the smokeless tobacco users in comparison with the normal controls (30).

Dhonde et al. evaluated salivary MDA (a marker of oxidative stress) and salivary uric acid (a marker antioxidant) in the tobacco chewers. Salivary MDA levels were elevated in the study group. They stated that increased mean uric acid levels, though having no significant effect, may indicate the initial phase of cellular injury (31). Kurtul et al. concluded salivary total sialic acid and MDA levels increased in smokeless tobacco users and smokers (32).

In a study by Shetty et al., elevation in the levels of salivary MDA was observed in healthy controls with tobacco-related habits (quid chewing and/or smoking), subjects with premalignant lesions, and subjects with OSCC (33). In some studies, salivary MDA (as a marker of lipid peroxidation) and salivary glutathione (as an antioxidant marker) were studied in individuals with OSCC and people with pre-malignant. The studies revealed increased MDA levels in the saliva of pre-malignant and OSCC individuals compared to controls. Also, significant declines were observed in salivary glutathione levels in pre-malignant and OSCC patients compared to controls (Table 3) (27, 34).

| Authors | Antioxidants & Oxidants | Level in Patients with OSCC | Level in Smokeless Tobacco Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arbabi-kalati et al. (29) | Glutathione peroxide | Increase | |

| Superoxide dismutase | Decrease | ||

| Dhonde et al. (31) | Malondialdehyde | Increase | |

| Begum et al. (30) | Malondialdehyde | Increase | |

| Nitric oxide | Increase | ||

| Superoxide dismutase | Decrease | ||

| Glutathione peroxidase | Decrease | ||

| Glutathione S-Transferase | Decrease | ||

| Catalase | Decrease | ||

| Kurtul et al. (32) | Malondialdehyde | Increase | |

| Shetty et al. (33) | Malondialdehyde | Increase | Increase |

| Shivashankara et al. (27) | Malondialdehyde | Increase | |

| Glutathione | Decrease | ||

| Metgud et al. (34) | Malondialdehyde | Increasea | |

| Glutathione | Decreasea |

Summary of Salivary Antioxidants and Oxidants in Smokeless Tobacco Users and Patients with OSCC

3.4. Glycosylation Related Molecules

Sialic acids have a significant role in the progress of neoplastic activities as important compounds of cell membranes. Those are sugar compounds at the end of oligosaccharide chains of glycoproteins and glycolipids (35).

In a study by Mollashahi et al., the level of salivary free sialic acid was higher in smokeless tobacco users than in healthy people (36). Some studies showed evaluated salivary levels of sialic acid and total protein in the OSCC patients and healthy control. The results showed that salivary levels of total protein, protein-bound sialic acid, and free sialic acid were increased much more significantly in OSCC patients than in normal healthy controls (37, 38).

Achalli et al. showed that the mean serum and salivary sialic acid levels were significantly increased in people with oral premalignant lesions and oral cancer than in healthy controls (39). Hemalatha et al. reported that salivary Sialic acid (free & protein-bound) levels were significantly raised in OSCC patients and individuals with oral leukoplakia compared to control groups (40).

In different types of neoplastic changes, cellular glycosylation changes have been observed. α-L-fucosidase is a lysosomal enzyme that intervened in the homeostasis of fucose metabolism. It has been indicated that changes in serum and tissue α-L-fucosidase activity may be valuable in the recognition and management of cancer persons (41).

In a study by Vajaria et al., serum and salivary total sialic acid/total protein ratios and α-l-fucosidase levels were elevated in oral premalignant and OSCC persons compared to the control groups; also, these salivary markers were increased in all subjects with a history of tobacco habits (Table 4) (42).

| Authors | Marker | Level in Patients with OSCC | Level in Smokeless Tobacco Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mollashahi et al. (36) | Sialic acid | Increase | |

| Sanjay et al. (37) | Sialic acid | Increase | |

| Achalli et al. (39) | Sialic acid | Increase | |

| Hemalatha et al. (40) | Sialic acid | Increasea | |

| Vajaria et al. (42) | Sialic acid | Increasea | |

| α-l-fucosidase | Increasea | ||

| Mohan et al. (43) | Lactate dehydrogenase | Increase | |

| Mantri et al. (44) | Lactate dehydrogenase | Increase | Increase |

| Samlin et al. (45) | Lactate dehydrogenase | Increase | |

| Goyal (46) | Lactate dehydrogenase | Increase | Increase |

Summary of Salivary Sialic Acid, α-L-fucosidase, and Lactate dehydrogenase in Smokeless Tobacco Users and Patients with OSCC

3.5. Lactate Dehydrogenase

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is a ubiquitous enzyme, the main function of which is to catalyze the oxidation of lactate to pyruvate. The oral epithelium is the main source of salivary LDH, which is derived from the surface exfoliated cells. Therefore, LDH concentration in saliva is presented in cellular necrosis (47).

Mohan et al. showed a significant difference in salivary LDH levels between the control group and tobacco users’ subjects and also healthy controls and potentially malignant disorders subjects. So, the evaluation of the salivary LDH level could be a valid marker to recognize the potentially malignant disease and also to monitor the tobacco users (43).

Mantri et al. evaluated salivary LDH levels in healthy people, oral cancer patients, oral submucous fibrosis patients, and habitual tobacco chewers (tobacco addiction without any disease). LDH activity was increased in the saliva of patients with habitual tobacco chewing, resulting in oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF), and oral cancer consistently (44). Samlin et al. concluded that salivary LDH level was higher in individuals with oral leukoplakia, oral submucous fibrosis, and oral carcinoma compared to the control group (45).

In a study conducted by Goyal, patients were divided into healthy, a history of tobacco use, pre-malignant lesions, and oral cancer groups. The amount of LDH saliva increased from the first to the fifth group, and it has been stated that LDH could be considered a sensitive marker for the revealing of dysplasia with already existing pre-malignant and OSCC lesions (Table 4) (46).

4. Conclusions

In this review study, some salivary markers, such as cytokines, immunoglobulins, antioxidants, etc. were reviewed. In this review, it was shown that similar changes in these markers occur in patients with cancer and smokeless tobacco users. With the development of these diagnostic markers, these may be used as a screening tool for early detection of OSCC in smokeless tobacco users.