1. Background

Although several options were suggested for the operation of gastric cancer, total gastrectomy is still a mainstay of the cardia and proximal gastric cancer curative treatment (1, 2). The standard method for reconstruction is Roux-en-Y (R&Y) reconstruction with or without jejunal J-pouch, which has several negative points such as malabsorption, loss of appetite, and abdominal discomfort (1-8). The most important reasons for weight loss after total gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction are relative anorexia, esophagitis, dysphagia, reserval insufficiency, and reduction of food-digestive juice blending (2, 3, 8-11).

2. Objectives

In our opinion the creation of an appropriate food reserve with a natural conduit that food can pass through the duodenum may help patients to have more normal diet habits and prevent severe weight loss. In this study, we use the ileocolic interposition technique as a gastric substitute in patients with total gastrectomy and checked the technical problems, complications, nutritional status, and weight changes.

3. Methods

The study enrolled 8 patients with proximal gastric cancer from December 2016 to October 2018 after the approval of the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1396.3164). All patients had biopsy-proven gastric adenocarcinoma. Patients who had comorbidity including diabetic mellitus, end-stage renal disease, ischemic heart disease, or heart failure were not enrolled in the study. Besides, patients who are immunocompromised or take corticosteroids were excluded. All patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy (3 cycles of EOX [Epirubicin, Oxaliplatin, and Capecitabine]). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients. Chemical and mechanical bowel prep was done before the operation for all patients.

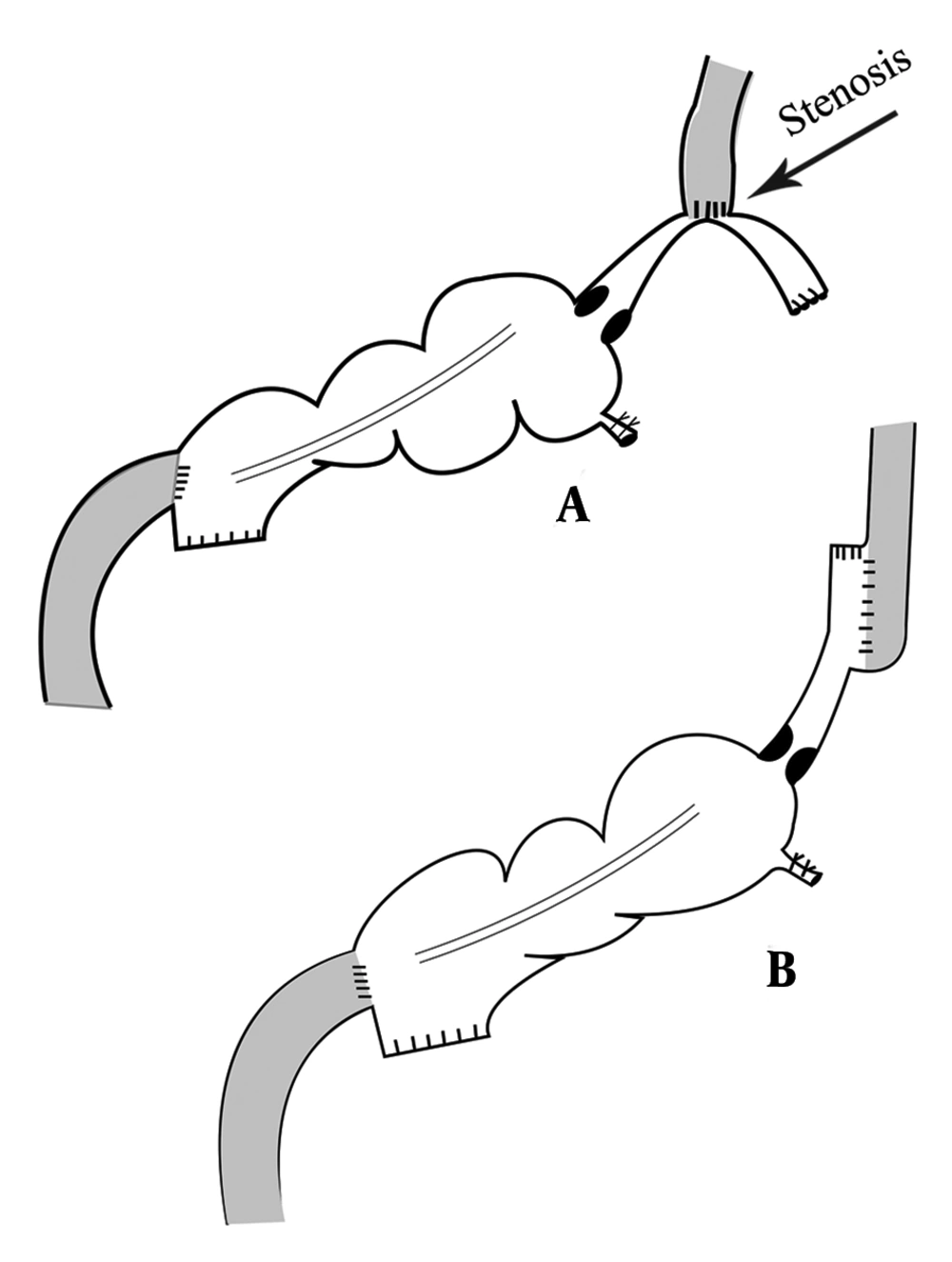

All participants underwent general anesthesia with the same anesthetic protocol (induction with midazolam, fentanyl, atracurium, and thiopental sodium; maintenance with propofol and N2O). The operation was done by a large median incision, and after assurance of operability and absence of metastatic disease, total gastrectomy with omentectomy and D2 lymphadenectomy was performed. The esophagus was cut with an acceptable margin from the tumor. Then, the small bowel was cut about 15cm from the ileocecal valve and the colon was cut at the hepatic flexure, while the vascular tree was carefully preserved. Then, a side to side anastomosis was performed between the remained ileum and transverse colon by two 80 mm gastrointestinal anastomosis stapler (GIA), and the mesentery defect was repaired. For the first two patients, esophagoileostomy was done by a circular stapler (25 mm) and the narrow lumen of the ileum makes the entry of the stapler more challenging. Also, a large amount of bowel wall was cut by the stapler and the risk of stenosis was elevated (Figure 1, part A). So, we decided to use side to side anastomosis technique by a 60 mm GIA stapler for esophagoileostomy anastomosis. The remained orifice was repaired by polydioxanone (PDS) suture on a large nasogastric tube in a horizontal manner. Anastomosis between colon and duodenum was performed by a 29 mm circular stapler. The end of the colon was closed by a 60 mm GIA stapler. A closed drain was placed in the upper abdomen. The double ligation technique was used for appendectomy in all patients.

As prophylaxis, all participants received intravenous antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole 3 days before and after the operation) and Enoxaparin (40 - 60 mg daily). Besides, we prescribed intravenous vitamin C (1 gr) and vitamin A (25,000 U) for 3 days postoperatively.

Nasogastric tube (NGT) was removed on the second day, and oral nutrition started with water and tea (favorite Iranian drink). The liquid diet started on the third day. Patients were discharged from the hospital on the fifth day.

Operation time, intraoperative bleeding, postoperative intra-abdominal complications (e.g., anastomosis leakage or abscess formation), surgical site infection, the problem in feeding, and weight of the patient in the appropriate interval (preoperative, early post-operation, and then monthly up to six months) were recorded. An upper gastrointestinal (GI) series with barium sulfate at the third month and upper endoscopy at the sixth month were requested. After the data collection, statistical analysis was performed.

4. Result

The patient’s characteristics are shown in Table 1. Among 8 patients enrolled in the study, 5 (62.5 %) were female and 3 patients were male. The mean age of the patients was 44.62. The tumor was intestinal type and diffuse type in 5 and 3 patients, respectively. In the sixth patient, the tumor raised from cardia (without considering Siewert type), and in two patients, the tumor was seen in the fundus.

| Age | Sex | Tumor Type (Adenocarcinoma) | Tumor Site | T Staging | N Staging | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | M | Intestinal type | Cardia | 3 | 2 | 23 |

| 2 | 48 | F | Diffuse type | Cardia | 2 | 0 | 19 |

| 3 | 32 | F | Intestinal type | Fundus | 2 | 1 | 18 |

| 4 | 27 | F | Diffuse type | Cardia | 3 | 1 | 19 |

| 5 | 64 | M | Intestinal type | Cardia | 3 | 1 | 22 |

| 6 | 53 | M | Intestinal type | Cardia | 2 | 2 | 22 |

| 7 | 33 | F | Diffuse type | Fundus | 3 | 1 | 19 |

| 8 | 47 | F | Intestinal type | Cardia | 3 | 1 | 21 |

All patients suffered from anorexia, nausea, some degree of dysphagia, and weight loss (mean: 7.32 kg), but nutritional status before the operation was acceptable (mean protein level: 6.1 g/dL and mean albumin level: 3.4 g/dL). None of them needed to receive packed red blood cells, albumin, and parenteral nutrition before the operation.

Intraoperative events are recorded in Table 2. Based on the data, by rising the experience of the surgical team, the time of operation was reduced. The amount of blood loss and need for transfusion were acceptable.

aTime of operation: from induction of anesthesia up to transfer to the recovery room.

bEvaluation of blood loss was based on the suction contain and bloody surgical pads.

cBlood transfusion was based on anesthesia judgment and according to the amount of blood loss before operation hemoglobin and vital sign of the patient.

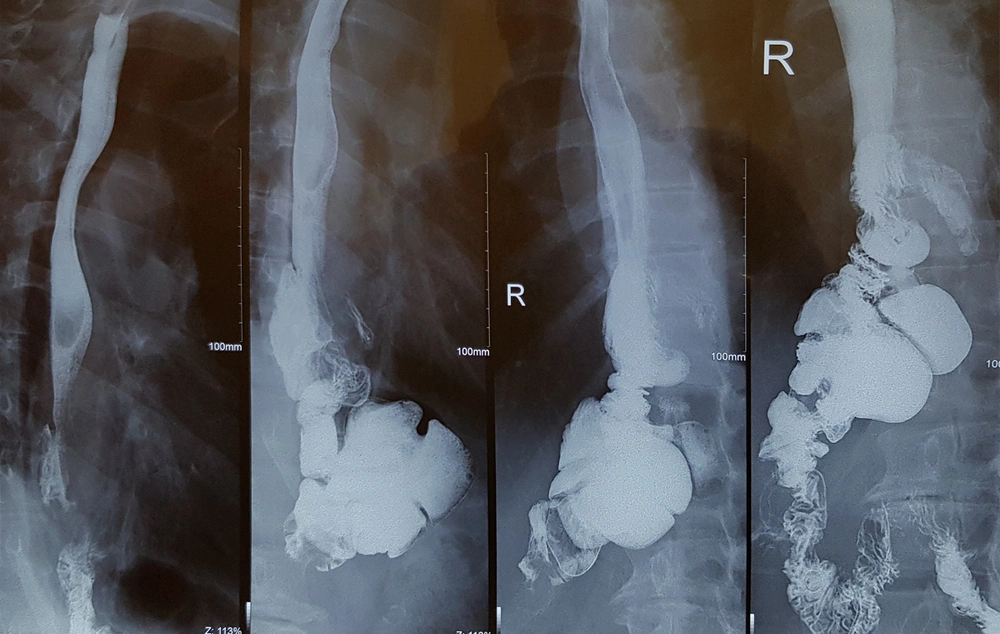

Postoperative complications and events are shown in Table 3. Fortunately, none of the patients suffered from anastomotic site leakage, abscess formation, or wound infection. In the first two patients, the anastomosis between the esophagus and ileum was performed by a circular stapler (conventional form). We have some challenges during surgery. The diameter of the ileum is narrower than the jejunum and because of wall thickening, this part of the bowel is less expandable. So, the stapler could not pass through it easily. Also, a large part of the bowel was cut by the stapler during anastomosis and we created post-anastomosis stenosis by this technique. Although we did not see major complications, the patients suffered from mild to moderate dysphagia and sometimes early post-meal vomiting. As the dysphagia of the first patient get worse with cold liquid and the contraction of the ileocecal valve may be a contributory factor, we start oral Diltiazem (60 mg/day). Interestingly, dysphagia disappeared after 3 months and we stop medication after 6 months of operation. But Diltiazem was not effective for the second patient and the Upper GI series realized stenosis in the anastomosis site (Figure 2). So, we were forced to perform an endoscopic dilation (twice), and dysphagia was revealed. For the remained patients, we performed side to side esophagoileostomy anastomosis. Fortunately, none of them had dysphagia or suffered from delays in the last patients. None of the patients suffered from delayed, chronic, or uncontrolled vomiting. Regarding the ability of belching, the patients were not the same. Three of them could belch normally, one patient could not and the others belch but not normally as before the operation.

| Patients | Anastomosis Leakage | Inter-abdominal Abscess | Surgical Site Infection | Dysphagia | Early Post-meal Vomiting | Delay Vomiting | Ability of Belch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | For 3 months | Sometimes | 0 | Yes |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | For 6 months | Sometimes | 0 | No |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | No | 0 | No |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | No | 0 | Yes |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | No | 0 | Yes |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | No | 0 | No |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | No | 0 | Yes |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | No | 0 | Yes |

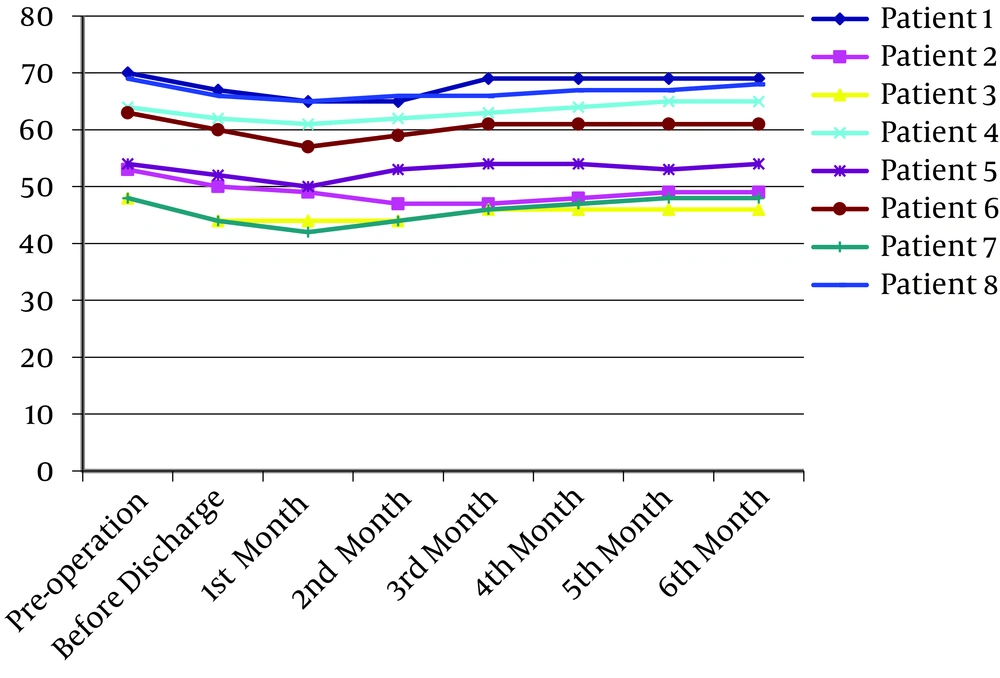

Patients' weight and body mass index (BMI) are recorded in Figure 3. All patients experienced weight loss postoperatively. This reduction continued for 2 months and after that, they gained weight, which was stable in 2 to 3 last months. Except for patient number 2, who suffered from dysphagia, this model was accepted for a large number of patients who underwent major abdominal surgery.

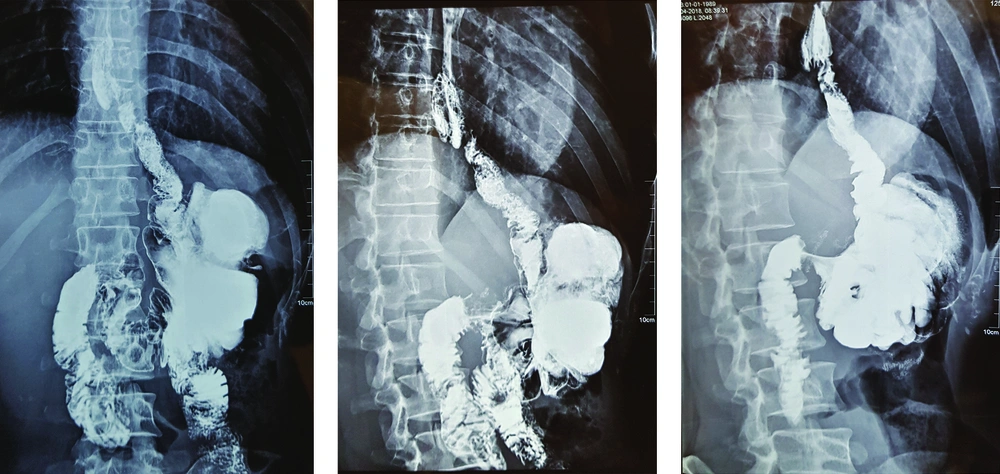

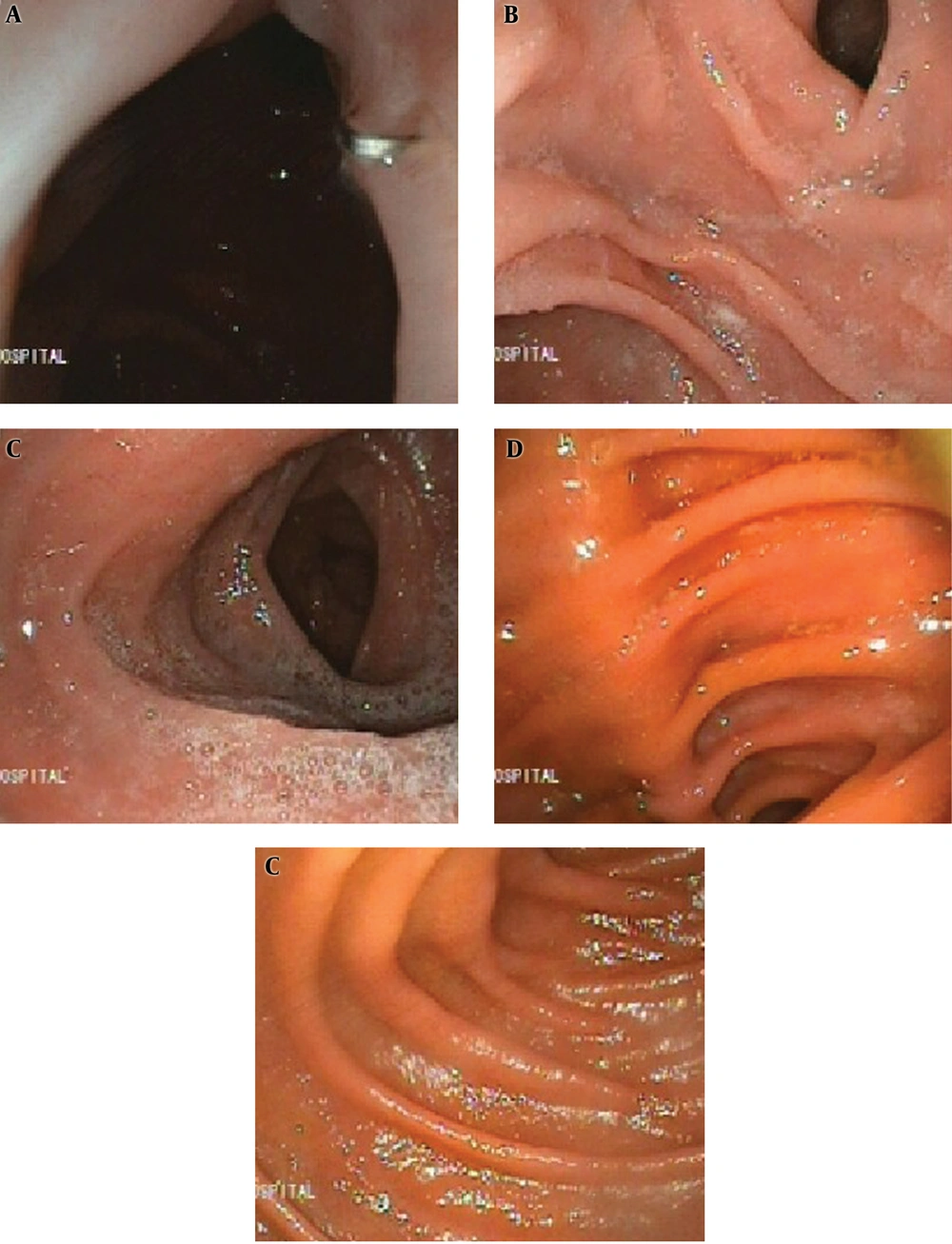

Barium examination and also upper endoscopy revealed that the patients had normal reserval volume, no evidence of erosion or ulceration, no evidence of biliary esophagitis or reflux, and absence of tumor relapse (Figures 4 and 5).

5. Discussion

Despite incredible advances in the treatment of tumors, gastric cancer swaggers in the top level of causes of cancer death list in the world (1). Up to now, surgery remains the mainstay of treatment of this disease (3). In patients who are a candidate for total gastrectomy, reconstruction of the elementary system is a challenge. Although several types of reconstruction have been suggested, up to now Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy with or without jejunal pouch is the method of choice (3). Although this acceptable technique helps a large number of patients, it can cause several complications and morbidities. Weight loss, anorexia, osteoporosis, anemia (iron and/or vitamin B12 deficiency), and an anther large list of metabolic and nutritional changes are some of these complications, all of which are related to digestion and absorption of food (1-8). In fact, what is seen by surgeons is even by cure evidence of disease, the patients suffer from several problems-such as prolonged and incomplete recovery, depression, reduction of level of social activities and chronic weakness- created by impaired food intake (1).

Some of these complications are related to the absence of the stomach itself – such as vitamin B12 deficiency anemia and food intake suppression by high amounts release of cholecystokinin in response to a meal- which cannot be corrected by surgical techniques (2, 12-14). In contrast, a large number of these complications are the result of Roux-en-Y reconstruction. We should alert that in this technique, the food reserval is reduced, normal food passage through the duodenum is absent, problems such as Roux limb syndrome and dumping syndrome are common and esophageal reflux, especially after lying down is annoying (11, 15, 16). Besides, this operation is performed on a patient, who suffered from cancer and has some courses of neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant chemotherapy, both of which have several physical and psychological side effects. Perhaps, it is not an exaggerated speech that we performed bariatric surgery in a cancer patient and we help the disease to have a less strong host.

Based on this concept, some techniques such as the jejunal J-pouch, jejunal interposition, jejunal interposition with the pouch, aboral pouch, and colon interposition were suggested, each of which has some problems (1, 3, 15). For example, the jejunal J-pouch and Aboral pouch cannot solve the duodenal food passage, and jejunal and colon interposition techniques create biliary reflux esophagitis, which is unbearable (3, 17).

Another option is ileocolic interposition. Theoretically, using this technique can create an acceptable food reserval and an effective mixture of the meal with pancreatic and biliary juices, and consequently better food absorption.

The cecum and ascending colon can store an acceptable volume of food. The absence of good musculature of the colon wall makes the fear of colon dilation after some time but selecting not too long part of the colon and absence of pylorus valve help to resolve this concern. Barium study and upper endoscopy of our patients established that although another concern for this technique was biliary esophagitis, apparently, the ileocecal valve work as a new lower esophageal sphincter (LES) correctly. In the endoscopy of our patients, we were surprised by the absence of any finding of esophagitis or colitis but the long-term influence should be considered.

In spite of another blind spot for this technique, which was fear of anastomosis between high secretory duodenum to a poor blood supply colon, we did not see any related complications such as fistula or anastomosis disruption. Selecting patients in middle age and younger, checking the ileocolic artery patency before surgery or intraoperative, reinforcement of anastomosis between colon and duodenum, and placement of nasogastric tube for decompression can prohibit the risk of anastomosis disruption.

Despite the above findings, we should not forget that the Achilles Heel of this technique is the complexity and time-consuming of that, which is not suitable for older patients or who have comorbidities. Also, the risk of internal hernias due to mesenteric defects is a potential concern.

We suggest an appropriate patient selection, preparing modern surgical equipment, and an experienced surgical team in cancer surgery are critical points that should be considered before deciding to perform this technique. Besides, to compare the clinical results of this surgical technique with other reconstruction methods, studies with a higher number of participants as well as longer follow-up times should be designed and performed.

5.1. Conclusions

We conclude that, because of the nutritional benefits of ileocolic interposition after total gastrectomy in gastric cancer treatment, it can be used as an acceptable alternative method of reconstruction in a subgroup of selected patients.