1. Background

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide and it is estimated to have killed 9.6 million people all around the world in 2018 (1). Since technical interventions in this field have not been able to respond to patients' problems on their own, the focus on factors such as health and life satisfaction is increasing in different societies (2).

One of the concepts associated with these aspects is life satisfaction, which represents “an overall assessment of one's quality of life according to one's chosen criteria” (3) and encompasses one’s general assessment and attitude towards the whole life and/or specific aspects of relevance, i.e. family life, friends, workplace, future perspectives, and health situation. This concept indicates how satisfied someone is with his/her life in general and with respect to specific aspects. To make these domains measurable, these different aspects sum up to a general feeling of ‘being well’. Satisfaction is influenced by a person´s psychological status, social interactions (4), and features such as race, socioeconomic status, marital status, education, and social engagement (5-7). In addition, different levels of self-esteem, the presence or the absence of depression, and the degree of one’s control over different conditions may vary among individuals (8) and these will influence a person´s perception of wellbeing, too.

Life satisfaction is associated with positive outcomes including health (9). Evaluative well-being in terms of ‘life satisfaction’ (or happiness) can be related to lower mortality, although the findings are not always consistent (10). Therefore, it is one of the most important factors in one's well-being, and studying it in health care systems is vital due to the strong relationship between physical and mental health (11). Therefore, care providers should assess and improve patients’ life satisfaction in physical, spiritual, mental, and social aspects.

Life satisfaction in patients with cancer and survivors is a concept used more widely in clinical studies (12). By emphasizing the fact that 11 million out of 15 million patients with cancer live for more than 60 years, studying this concept is significantly important (13).

In Iran, due to the shortage or the lack of such appropriate and standard instruments, there is not much information available on life satisfaction in patients with cancer. In order to assess life satisfaction in patients with cancer, an instrument with scientific characteristics, based on psychometric principles is needed. Experts believe that the content of an instrument should be appropriate and be in harmony with the culture and the lifestyle of the communities and the countries in which the instrument is used. This is because the tool designed in a particular community not only reflects the language and the culture of that community but also its utilization in other communities is followed by many problems, even with an accurate translation due to incompatibility with content (14, 15).

In 2009, Büssing et al. developed the Brief Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale (BMLSS) in order to measure life satisfaction in patients with chronic diseases (16). This questionnaire is derived from the Brief Multidimensional Students' Life Satisfaction Scale, designed by Huebner et al. in 2004 (17). The instrument addresses key dimensions of life satisfaction including intrinsic dimension, social dimension, external dimension, perspective dimension, and health dimension (BMLSS-10 main module); a further optional module assesses the amount of one’s satisfaction with the support one receives from their partner, family, and care providers (BMLSS-Support module).

Based on the assessments made by the researchers, this tool has been translated in some countries such as England, Germany, Italy, Denmark, Poland, Lithuania, Spain, France, China, and Saudi Arabia. In addition, studies in Iran showed that the tool has been neither translated nor validated officially and systematically so far in the cultural context of Iran. Therefore, based on the above mentioned, and due to the need for standard and appropriate instruments in this field and because of the lack of valid instruments for the assessment of patients' life satisfaction, the present study was conducted with the aim of the translation and the psychometric evaluation of Persian version of Brief Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale (BMLSS) in Iranian patients with cancer.

2. Methods

The present study was methodological research (18), during which the BMLSS was translated and the Farsi version was validated for patients with cancer.

In this study, the BMLSS was translated and validated according to the method proposed by Wild et al. (19). After acquiring written permission from the original designer of the scale, and based on his opinion, mentioning that the psychometric evaluation of the first 10 items is sufficient, the scale was translated into Farsi by 2 expert translators in both English and Farsi (forward translation). Then the translations were compared and the final version was prepared after making slight changes to the vocabulary (the word “school” was removed from item H3, Reconciliation). In the next step, the translated final version was given to 2 both English and Farsi translators, who were not in contact with the first one. They did back-translate into English (back-translation) and were unaware of the procedure of the study. Then the research team who were completely familiar with the concept, compared the back translation to ensure its similarity with the original version of the scale, and some grammatical corrections were applied to the Farsi version (back-translation review). Afterward, the psychometric evaluation of the translated scale was done by measuring the content validity, the face validity, and the construct validity and determining the reliability.

In order to examine the qualitative content validity, the translated scale was given to 10 experts including 2 clinical psychologists, 1 internist, 3 nursing instructors, and 4 nursing associate professors with experiences in developing instruments. They were asked to review the scale and propose their corrective comments. Then, in order to assess the face validity, 10 patients with cancer were provided with the scale, based on the inclusion criteria, to express their opinions on its ease of use and the understandability of sentences and expressions. The Farsi version was finalized without making any significant changes to the sentences (20, 21).

The construct validity was assessed by performing confirmatory factor analysis and determining the convergent validity. The research population consisted of hospitalized patients with cancer in the oncology wards of the selected teaching hospitals in Iran within 4 months (June to September 2019). Convenience sampling was used based on the inclusion criteria to achieve a sufficient sample size for the confirmatory factor analysis. Given the individuals’ willingness to participate in the study, the inclusion criteria included an age range of 25 - 70 years, at least 6 months of being diagnosed, not being at the end-of-life stage, being aware of the disease, the ability to understand and speak Farsi, no other serious concurrent disease, and no history of mental illnesses.

In the confirmatory factor analysis, the sample size is determined based on the factors and a sample size of 200 is recommended in the factor analysis (18-22). Finally, based on these criteria, 222 samples were selected. The confirmatory factor analysis was performed to examine the construct validity and the fit of the model using the statistical software LISREL 8.5. CFA is a technique to propose a structural equation modeling used to determine the goodness-of-fit between a hypothetical model and the data obtained from the research samples (22).

In order to perform confirmatory factor analysis, discriminant validity was examined in the 5-factor and 2-dimensional model of the mentioned instrument which was found to be unidimensional so far. The analysis was made by comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) with the square of the correlation between dimensions. If for most factors, AVE is lower than the square of their correlation with other dimensions, it means that the square of the correlation between factors is higher than the AVE of dimensions and there is an overlap between the dimensions. Therefore, no divergence exists between some dimensions and the discriminant validity of the tool is not approved.

The maximum-likelihood algorithm was used to examine the fit of the model. There are many fit indices to decide whether a model is suitable or not, and it is recommended to use several different indices (23-25). In this study, the fit indices were used (Table 1). The Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) was used to determine the convergent validity, and the correlation between BMLSS the Spiritual Well-Being Scale was calculated (26-28).

| Fit Indices | Optimal Values | The Values Obtained in the Study |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 1 - 5 | 3.9 |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | Greater than 0.90 | 0.94 |

| Non Normed Fit index (NNFI) | Greater than 0.90 | 0.94 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | Greater than 0.95 | 0.96 |

| Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | Greater than 0.90 | 0.96 |

| Relative Fit Index (RFI) | Greater than 0.90 | 0.97 |

| Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) | Smaller than 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) | Smaller than 0.05 | 0.061 |

The Values of Fit Indices for the Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model of BMLSS

The internal consistency and stability were measure using SPSS 19 software (29). The internal consistency of the scale was assessed by calculating the Cronbach's alpha for the whole scale and each of the dimensions. The stability was examined through calculating the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) by performing the test on 15 patients meeting the inclusion criteria, on 2 occasions with a 2-week interval.

2.1. Study Instrument

The demographic characteristics questionnaire developed and utilized by the research team which included age, sex, the level of education, marital status, occupation, the source of income, the treatment type, the use of medicines, recreational activities, sports activities, the use of social services, and whether one regards oneself religious or not.

The Brief Multidimensional Life Satisfaction Scale (BMLSS): Büssing et al. (2009) developed the scale to measure life satisfaction in patients with chronic diseases. The instrument consists of the following 5 dimensions of satisfaction: intrinsic dimension (one’s self, overall life), social dimension (family life and friendships), external dimension (work and where one lives), perspective dimension (financial status, future prospects), health (health status and the ability to cope with daily life concerns). A further optional add-on assesses one’s satisfaction with the support provided by a life partner, family, medical team, psychologist, and spiritual therapist (BMLSS-Support). Both modules were intended as independent measures, the BMLSS-10 (with the items H1-H8, G1, G3) representing the main module, and the BMLL-Support module (with items TC1-TC5) assesses satisfaction with the support provided and received. In the present study, the 10-item format, including the intrinsic dimension, the social dimension, the external dimension, and perspective were studied and psychometrically evaluated. The scale is scored based on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from complete “dissatisfaction” to “complete satisfaction”. The internal consistency of the 10-item scale is approved by calculating the Cronbach's alpha as 0.92 (16).

The Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS) developed by Paloutzian& Ellison (1982) consists of 20 items with the 2 subscales existential well-being and religious well-being. The first dimension of the construction of spiritual wellbeing focuses on experiencing the satisfaction in communication with God and is a subscale of religious health. The second dimension is assigned to the sense of satisfaction with life and its purpose. The items on this scale are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the dimensions of existential well-being and religious well-being and the whole scale are reported to be 0.91, 0.91, and 0.93, respectively (30). In this study, the cognitive evaluation of the scales (BMLSS and SWBS) was done using the opinions of 10 patients meeting the inclusion criteria. Cronbach's alpha for the whole scale and each of the dimensions of existential well-being and religious well-being are reported as 0.94, 0.93, and 0.96, respectively.

After selecting the participants and explaining the purpose of the study and the research method, they completed the informed consents form, and at the appropriate time, while still hospitalized but physically and mentally prepared, they were asked to complete the research instruments. For the illiterate, the research instrument phrases were read by the researcher and their responses were marked. The response time for the research instrument was 5 - 10 minutes.

2.2. Ethical Consideration

This research was conducted as a proposal approved by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The current research was done based on the codes of ethics in order to observe the ethical considerations and the rights of participants. After obtaining the necessary permits from the Research Deputy of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and the selected teaching hospitals, introducing the researchers and explaining the purpose and the methodology of the research, written informed consents were obtained from the samples and data collection was started. The samples were also ensured of the confidentiality of the data and made aware of the right to withdraw from the study at any stage.

This study has been proposed to the Ethics Committee on 07/05/2019 and was approved under the code IR.SBMU.CRC.REC.1399.002.

3. Results

A total of 222 questionnaires were evaluated and statistically analyzed. In this study, patients had a mean age of 47.7 ± 15.4 years. From the participants, 157 (71%) patients were female and 57 (26%) were male. Other demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| The level of education | ||

| Elementary | 94 | 42.35 |

| High school | 87 | 39.18 |

| Academic | 41 | 18.47 |

| Occupational status | ||

| Employed | 63 | 28.37 |

| Unemployed | 115 | 51.80 |

| Retired | 25 | 11.26 |

| Disabled | 19 | 8.57 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 168 | 75.67 |

| Single | 34 | 15.31 |

| Spouse | 20 | 9.02 |

| Recreational activities | ||

| Yes | 144 | 64.86 |

| No | 78 | 35.14 |

| Sport activities | ||

| Yes | 172 | 77.47 |

| No | 49 | 22.53 |

| In need to receive services from others | ||

| Yes | 162 | 72.97 |

| No | 60 | 27.03 |

Some Demographic Characteristics of Participants

The BMLSS items were investigated to determine whether these items are valid references for evaluating life satisfaction in patients with cancer and whether this instrument is applicable in Iranian society.

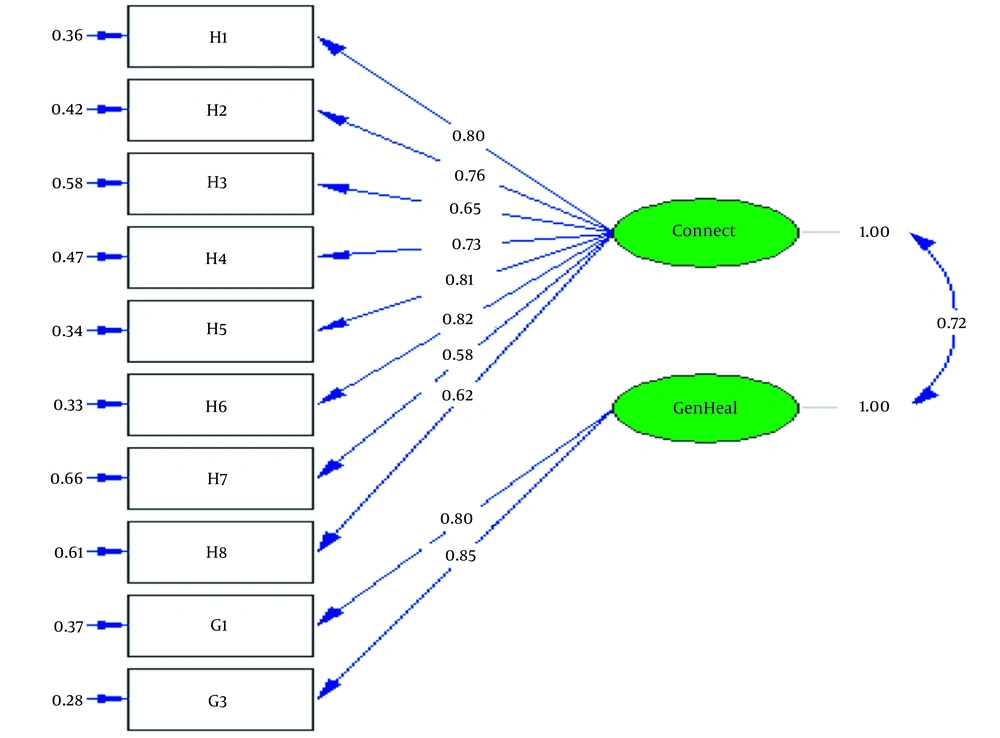

For discriminant validity, in the 2-dimensional model, the AVE was calculated to be 0.53 for the first dimension (items H1 to H8) and 0.68 for the second dimension (the items G1 and G3). Due to the fact that, for both dimensions, AVE was calculated to be higher than the square of the correlation between the 2 dimensions (0.52), the discriminant validity of the instrument was confirmed in the 2-factor model.

Thus, for the above instrument, 2 dimensions are confirmed. Based on the content of the items loaded on each dimension, the factors were named as follows: self-connectedness (the items H1 to H8) and general health (the items G1 and G3). The results of the standardized estimate model are displayed in Figure 1 and the values of fit indices in Table 1.

In order to investigate the convergent validity, the correlation between the spiritual well-being score (SWBS) in patients with cancer and the BMLSS score was determined (r = 0.58, P < 0.001).

After measuring the construct validity and confirming the proper fit of factors, the internal consistency for all items, and each factor separately, was determined in the sample of 222 individuals. Cronbach's alpha for the whole scale (0.90) and each dimension and the stability in time are presented in Table 3.

| The Whole Scale and Its Dimensions | BMLSS | Connectedness (the Items H1 to H8) | General Health (the Items G1 and G3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.81 |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | 0.93 | ||

The Stability and Internal Consistency Reliability of the BMLSS

The correlation between some demographic variables (age, sex, marital status, education, occupation, the sense of being religious, and income source) was included in the demographic characteristics questionnaire and the BMLSS score was measured. In this regard, there was a moderate to strong correlation between age (r = 0.51, P < 0.001) and the sense being religious (r = 0.44, P < 0.001) with BMLSS score.

4. Discussion

Due to the growing prevalence of cancer globally, the disease is considered one of the most important sources of stress, disability, and reduced life satisfaction. Although life satisfaction is supposed to be a relatively stable psychological construct, it may change in response to life events (4, 31). Since there was no valid and reliable instrument for studying investigating life satisfaction in cancer patients in Iran, this study is carried out with the aim of psychometric evaluation of BMLSS (with its two sub dimensions self-connectedness and general health) were introduced.

In this study, 2 dimensions are approved for the above instrument and the factors are named as general health and connectedness according to the content of the items that were placed in each one.

The dimension connectedness refers to communication in various dimensions such as communication with family, friends, self, work, and the place of residence. Blau et al. in the study on undergraduate students concluded that social communication promotes life satisfaction, and that as communication expands, the level of satisfaction increases (32). The results of another study showed that communication with friends leads to more life satisfaction, higher self-confidence, and happier life (33, 34). Among patients, establishing communication also plays an important role in promoting their satisfaction. For patients, this communication is associated with concepts such as intimacy, sense of belonging, empathy, caring, respect, trust, and reciprocity (35). Therefore, connectedness can be an important factor in the life satisfaction of patients with cancer, which was named as a subscale.

The dimension general health refers to individuals’ adaptation and health status. In a study on patients with rheumatoid arthritis, it was found that life satisfaction increases by promoting resilience and implementing emotion-oriented coping strategies (36). In patients who received palliative care, the use of spiritual adjustment and emotion-oriented coping strategies, especially in female patients, led to an improved quality of life (37), and as a result, life satisfaction. Promoting coping and adjustment, by making positive changes in patients' mood, leads to the improvement of health-related quality of life in them (38, 39), which in turn, results in greater satisfaction with the existing conditions.

In this study, the methodological stages were performed step by step, and the content validity, the face validity, and the construct validity were measured. Expert opinions were used to confirm the content validity and to measure the cultural appropriateness of the BMLSS instrument.

Confirmatory factor analysis was used to measure the construct validity of the instrument. The purpose of the confirmatory factor analysis is to discover whether the research data support the theoretical model proposed by the developers of the instrument (18). According to the results of the research, the indices calculated were desirable and the model was relatively fit. These results are consistent with the results obtained from the original version of the BMLSS (16). Some studies have used exploratory factor analysis to validate this scale. Büssing et al. reported that the results of the exploratory factor analysis performed on the Polish version of the BMLSS-10 were quite similar to the original 2-dimensional version of the instrument (40). Lorenzo-Seva et al. by performing confirmatory and exploratory factor analysis on Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), showed that the instrument is basically one-dimensional with acceptable internal consistency, construct, and fit and is dependent on age, sex, cancer status, and the location of the tumor (41). The results of the factor loadings of the 5-dimensional students´ BMSLSS instrument ranged from 0.51 to 0.69 which provides supplementary evidence to confirm the construct validity of the instrument (42).

Reliability is the most important concern when using a psychological test. According to the results of the study, the Cronbach's alpha for the whole instrument and its dimensions is acceptable and desirable, as it is higher than 0.70. In the study by Büssing et al. (2009), Cronbach's alpha for the whole instrument was estimated to be 0.87 (16). Furthermore, Hashim and Areepattamannil reported a Cronbach's alpha and an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.82 of the students' BMSLSS (43).

The results of the retest may be regarded as evidence of the good stability of the scale over time. In this study, the intra-class correlation coefficient was calculated to be 0.93 between the 2 occasions on which the test was run, indicating proper scale stability.

The findings of this study showed that the amount of life satisfaction in BMLSS has a positive and significant relationship with age and the sense of being religious. The sense of being religious or practicing worship and increased dependence on God would increase a good feeling toward life which can be very helpful in supporting patients with cancer (25). In addition, in many cases, one feels that the current state of his/her life is due to the will of God and is, therefore, satisfied with life. Koenig has shown that prayer and communication with God play a significant role in patients’ physical and mental adaptation because communication with God may results in peace, reduced stress and anxiety, and make patients believe that God helps them in making decisions in regard to their lives. Worship and the tendency to spirituality cause changes in attitudes, functioning, and social behavior (44). However, this is only the positive side, because patients may also experience that God is not responding as they had expected, i.e. that they are still suffering, are not healed. As a consequence, some may not find inner peace, experience religious struggles, stop praying, etc. In secular Germany, the indicator of spirituality (particularly religious trust) is only marginally related to life satisfaction as measured with the BMLSS (45). Also in highly religious patients from Poland, life satisfaction is not generally elated to indicators of spirituality: Religious practices were not at all related, while the perception of awe/gratitude an indicator of perceptive spirituality was weakly associated (46). Further, in Catholic Polish person's religious trust in God was weakly only related to their life satisfaction (47).

In Iran, religious practices such as prayer are also among the most important approaches to promoting individuals’ health (48). In the original scale designed by Büssing et al., the overall BMLSS score was strongly correlated with positive life construction as an intrinsic coping strategy and mental and emotional well-being (16).

Tendency to spirituality results in changing people’s attitudes. The more positive one's attitude towards life, especially spiritually, the better he/she can use adaptive strategies in critical situations and control his/her emotions (49). The results of various studies showed that spirituality and the sense of being religious are among the best coping strategies for solving the problems caused by chronic diseases, especially cancer (25, 44, 50).

According to investigations made in different countries, cultural and religious differences among participants might affect their assessments of life satisfaction (51-53). This is also the case regarding the participants in the current study. Culture is a background variable that influences one's assessment of life satisfaction, because the cultural system can lead to life satisfaction by developing one's self-esteem and individual identity (54, 55). On the other hand, as a part of the culture and religious socialization, religion may influence one’s life satisfaction in different ways. Religion grants one a sense of meaning in life and gives hope by creating inner peace and eliminating the sense of emptiness. In several religions, religious principles and rules propose a healthy way of life, while helping people receive the support of other individuals by participating in collective religious rituals and develop optimism and trust in others, which consequently increases their social capital and leads to satisfaction (56).

Patients with higher physical, mental, and emotional well-being are more bound to religious beliefs and easily communicate with other people (57). Since Büssing et al. reported that physical, mental and, emotional well-being have a significant relationship with positive attitudes, and based on the available evidence, these variables correlate with spirituality and the sense of being religious, which is consistent with the current research.

This study was conducted in Iran, where the majority of the population is Muslim and Shiite. Accordingly, in this study, 91% of the subjects regarded themselves as religious. The current study was conducted among Muslim and religious Iranians and there were no differences among participants in this regard.

On the other hand, since Iran is a vast country, with people of different ethnicities and cultures, the sensitivity of the issue and the need to pay attention to the cultural values of the society will cause limitations in the generalization of the findings to the whole country, although the samples had been chosen from all around the country.

4.1. Conclusion

Since the variable of life satisfaction is of significant importance in better health, a valid and reliable instrument is needed to assess the efficacy of the interventions, which are implemented for increasing life satisfaction. The results of this study showed that life satisfaction scale in patients with cancer has desirable psychometric properties and can be used as a proper scale in some research protocols in different settings. Moreover, due to the religious atmosphere of Iran and the correlation between the sense of being religious and the level of satisfaction in patients with cancer, it is possible to use this instrument to estimate the level of satisfaction.

Moreover, it is recommended to assess the other psychometric properties of the instrument such as the discriminant validity in a research population consisting of patients with other types of cancer.