1. Background

Breast cancer disease is an important public health trouble in the world. The research shows there are 2.3 million women with breast cancer and 685 000 deaths worldwide in 2020. The results indicated that 7.8 million women were with diagnosed breast cancer in the past 5 years and, as a result, breast cancer is the world’s most prevalent cancer. Research shows disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) due to breast cancer in women is more than in other cancer. Breast cancer mortality did not change much from the 1930s to the 1970s (1). The previous studies showed that the incidence of breast cancer has increased alarmingly among Iranian women (2, 3). They also encounter fatality because of the advanced stage of cancer (4).

Mammography screening can lead to early detection and management of breast cancer (5) and it also plays an important preventive role in decreasing breast cancer, especially among women over 40 years old (6). Apart from the quick rate of increase, it has also been seen to start at an earlier age as per statistics, which suggest that the mean age of Iranian women with breast cancer is 49.6 years (95%CI 49.5 - 49.6) (2) compared to 55 to 60 years among women in the United States (7) and 65 to 69 years in Australian women (8). Iranian women have been consistently reported as having low partnership in mammography practice and, unfortunately, their disease has spread due to delayed referrals, thus putting them at risk of dying from advanced cancer diagnosed (4). Because of this, breast cancer is considered a health priority in Iran (8). The health action process approach (HAPA) is a universal and psychological theory of health behavior change, developed by Ralf Schwarzer for assessing health promotion behaviors such as breast cancer (9). There is no valid Persian instrument for evaluating influential factors.

2. Objectives

This paper aimed at reporting the psychometric properties of a questionnaire on mammography behavior based on HAPA.

3. Methods

In this cross-sectional study in the first phase, a questionnaire including 41 items was developed based on literature about the mentioned constructs of HAPA and preventing breast cancer behavior. In the second phase, healthcare professionals discussed the initial instrument. This initial item was piloted and, then, reduced via item analysis and scaling methods (10-14).

The face validity was determined by 70 women, who had similar characteristics to the study sample and qualified for participation based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria were age 40 years and older, being literate, and having a mental and disabling disorder. The age of participants should be older than 40 years because basic mammography is recommended at the age of 40 years. The exclusion criteria were women with a positive history of breast cancer in their family or friends, as well as if someone suffered from any defect or disease that interfered with mammography. In the qualitative approach, the ‘ambiguity’, ‘relevancy’, and ‘difficulty’ of the tool were assessed by 70 women older than 40 years. At this stage, 4 items improved. In the qualitative method, the content validity was assessed by an expert panel and 22 members, including 8 health educators, 7 specialize in reproductive health and gynecology, 5 psychologists, and 2 oncologists and content validity ratio (CVR) and the content validity index (CVI) were evaluated. According to Lawsh as cited in Wilson et al. (15), CVR with a score < 0.418 was deleted and a CVI value of 0.78 or above was considered satisfactory for each statement (16).

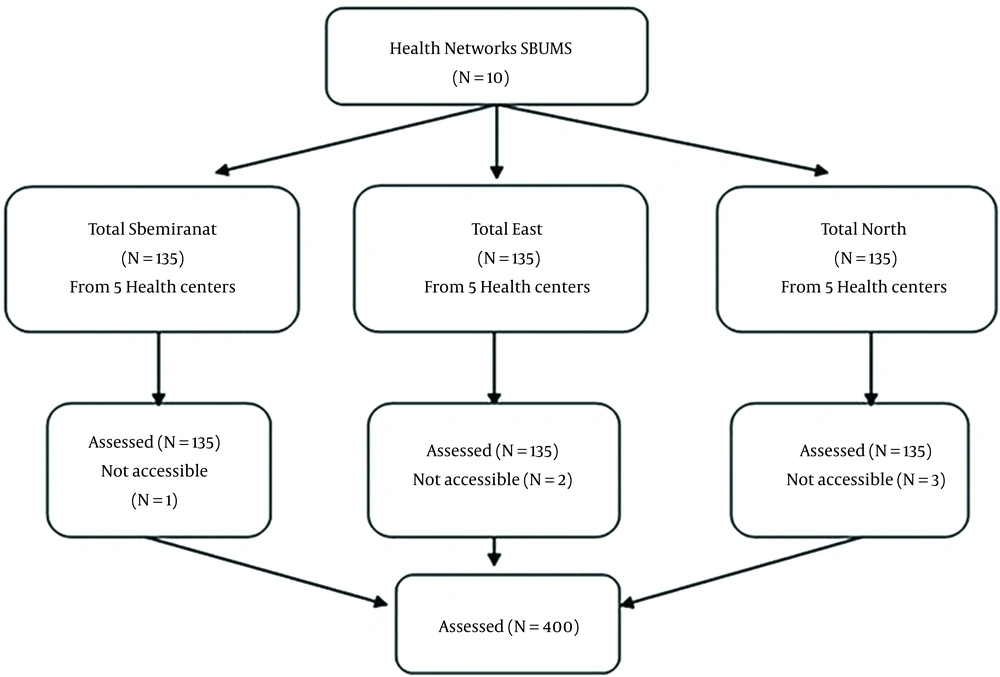

The subjects were selected by multi-stage cluster sampling. Firstly, among the 10 health networks under the auspices of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, 3 health networks were selected. In the next phase, 5 health centers were randomly selected from each network. Then, 80 people were selected from each center in equal proportions.

The ideal sample size based on exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was estimated at 4 to 10 participants for each item (45 × 9 ~ 400) (17). Figure 1 presents the procedure of sampling. The primary questionnaire included 20 demographic variables and the questionnaire had 45 items relevant to 8 HAPA constructs. The construct validity of the questionnaire was examined by EFA.

Principal component analysis was performed by varimax rotation to extract the essential factors and factor loadings 0.5 ≥ were properly considered. For determining the range of statements eigenvalues above one and scree plots were applied. For proper sample size, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (KMO = 0.73) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (P < 0.001) were used. The internal consistency was calculated by infraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values. The appropriate amount for ICC was considered (ICC ≥ 0. 4). Data analyses was done, using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS).

3.1. Measures

A self-report measure was done for assessing the constructs of the HAPA model of mammography behavior. The participants answered each item based on a Likert 5-point scale from strongly disagree (score 1) to strongly agree (score 5) and higher scores indicating a better status of the responder in that scale towards mammography. RP was measured with 5 items about estimating the risk of breast cancer in the future. ‘My chances for developing breast cancer in the next 5 years is very high’ (12). The OE considered 6 items based on Ajzen’s recommendations (13). They were requested to assess the statement, ‘It makes me feel better about my health if I have a mammogram every year’ (14). Action self-efficacy (ASE) in mammography was measured with 12 different items based the Schwarzer’s recommendations (11). ‘How confident are you in having a mammogram, despite the barriers to mammography? I can start mammography even …’ (12). Intention to have a mammogram assessed with 5 items based on the recommendations of Ajzen (13) and Smith et al. (14). AP was measured with 3 items and CP was assessed with 4 items based on recommendations by Schwarzer et al. (10).

MSE assessed 6 items about people’s confidence in their ability to perform mammograms although they have been confronted with barriers. These barriers were extracted from previous mammography research (18, 19). RSE assessed 2 items about the research subjects’ beliefs about rate their confidence to go back to mammography even after discard (10). AC was determined by 2 items, each of which examines different aspects of self-monitoring action control and knowledge of standards. Mammography behavior and intention doing screening were distinguished as self-reported (14, 20, 21).

3.2. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University of Medical Sciences (ID: IR.TUM.REC.1395.328). First, the aims of the study were explained to women, and their written informed consent was obtained from participants.

4. Results

In this study, all the women (100%) were asked to fill in and return the HAPA questionnaire on mammography behavior. The mean age of the women was 45.6 ± 5.45 years and the level of education, 37.2% of women were less than high school (Table 1).

| Demographic | Value (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 45.6 ± 5.45 |

| Education Background | |

| Less than high school | 37.3 |

| High school/trade | 29.3 |

| More than high school | 32.9 |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 3.3 |

| Married | 88 |

| Divorced or widow | 8.7 |

| Having experience with breast cancer in friends and acquaintances | |

| Positive | 20 |

| Negative | 80 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation

4.1. Face Validity

The initial scale was held in focus groups with 70 women over 40 years old. They stated their opinions about the words and phrases in each item, clear to understand and misunderstand the questions. In general, some items were modified based on women’s viewpoints.

4.2. Content Validity

The content validity of the final version tool was determined by CVI and CVR. The results indicated (s-CVI/Ave) was 0.80. Based on Lawshe’s quantitative approach to the CVR, the minimum value was determined 0.79 and the findings suggested adequate content validity (15).

4.3. Construct Validity

The varimax rotation was used in factor analysis. In total, 4 items were deleted due to their incompatibility with the desired factor. Thus, the final scale had 41 items.

4.4. Reliability

The internal consistency was calculated with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80. Moreover, the test-retest ICC was 0.83 which was satisfactory. Table 2 shows the results of internal consistency.

| Factor and Scale Item | Factor Loading | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Risk perception | ||||||||

| Q1 | 0.759 | |||||||

| Q2 | 0.884 | |||||||

| Q3 | 0.855 | |||||||

| Q4 | 0.817 | |||||||

| Q5 | 0.531 | |||||||

| Outcome expectancies | ||||||||

| Q6 | 0.897 | |||||||

| Q7 | 0.897 | |||||||

| Q8 | 0.877 | |||||||

| Q9 | 0.884 | |||||||

| Q10 | 0.730 | |||||||

| Q11 | 0.533 | |||||||

| Action self-efficacy | ||||||||

| Q12 | 0.633 | |||||||

| Q13 | 0.671 | |||||||

| Q14 | 0.535 | |||||||

| Q15 | 0.441 | |||||||

| Q16 | 0.633 | |||||||

| Q17 | 0.438 | |||||||

| Q18 | 0.459 | |||||||

| Q19 | 0.764 | |||||||

| Q20 | 0.614 | |||||||

| Q21 | 0.535 | |||||||

| Q22 | 0.630 | |||||||

| Q23 | 0.752 | |||||||

| Action planning | ||||||||

| Q24 | 0.797 | |||||||

| Q25 | 0.843 | |||||||

| Q26 | 0.758 | |||||||

| Q27 | 0.794 | |||||||

| Coping planning | ||||||||

| Q28 | 0.843 | |||||||

| Q29 | 0.402 | |||||||

| Q30 | 0.850 | |||||||

| Q31 | 0.855 | |||||||

| Maintenance self-efficacy | ||||||||

| Q32 | 0.658 | |||||||

| Q33 | 0.436 | |||||||

| Q34 | 0.728 | |||||||

| Q35 | 0.658 | |||||||

| Q36 | 0.436 | |||||||

| Q37 | 0.767 | |||||||

| Recovery self-efficacy | ||||||||

| Q38 | 0.679 | |||||||

| Q39 | 0.666 | |||||||

| Action control | ||||||||

| Q40 | 0.598 | |||||||

| Q41 | 0.511 | |||||||

a Extraction method: Principal component analysis.

b Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser normalization

c Rotation converged in 10 iterations.

Table 3 shows the results of correlations between the motivational and volitional phases of HAPA with mammography intention. The finding indicated a significant correlation between intention mammography behavior and OE (r = 0.10, P < 0.05). The findings indicated a significant relationship between intention mammography and ASE (r = 0.36, P < 0.05) and AP (r = 0.32, P < 0.05). The finding indicated a significant correlation between volitional HAPA stage constructs and mammography behavior.

| Structure | Number of Items | Mean ± SD | Cronbach’s Alpha | ICC | Correlation (r) with Intention | Correlation (r) Mammography Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk perception | 5 | 15.5 ± 4.3 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.19 a | 0. 2 b |

| Outcome expectancies | 6 | 16.7 ± 7.1 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.10 a | 0.1 |

| Action self-efficacy | 12 | 21.11 ± 3.15 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.36 a | 0.4 b |

| Action planning | 4 | 4.17 ± 1.48 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.32 a | 0.33 b |

| Coping planning | 4 | 3.4 ± 1.37 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.12 a | 0.25 b |

| Maintenance self-efficacy | 6 | 13.3 ± 3.18 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.03 | 0.6 |

| Recovery self-efficacy | 2 | 2 ± 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| Action control | 2 | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.1 | 0.06 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; ICC, infraclass correlation coefficient

a Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed)

b Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed)

The analysis of the main factors with varimax rotation showed 8 structures accounting for 60.88% of the total variance.

5. Discussion

This study was conducted to design the Mammography Behavior Predicting Scale (MBPS) and evaluate its psychometric property questionnaire on mammography behavior based on HAPA.

Our findings underlined the favorable psychometric properties of this 41-item questionnaire and showed its enforceability as a tool to assess elements affecting mammography behavior. Mammography Behavior Predicting Scale was a valid and reliable measure.

The results indicated a significant correlation between the motivational stage constructs (action self-efficacy and coping planning) and mammography intention.

These findings were consistent with the concepts of HAPA (9), which show high correlations between behavioral intentions and self-efficacy. To better understand these findings, research is needed on a larger sample of women. In the study by Schwarzer et al. (10), the best direct predictor of mammography intention and AP was ASE. In the current study, planning was a key factor and the best direct predictor of mammography behavior. Consistent with our research, Schwarzer and Renner (11) showed there were correlations between RP and behavioral intention. Interestingly, there was a correlation between ASE and OE with mammography intentions. Regarding the relationship between the power of ASE and OE with behavioral intention, the power of the relationship between ASE with behavioral intention compared to OE was strongly related to the situation in other studies (22). According to the HAPA scale, OE and ASE have a high effect on the prediction of behavioral intention, while other studies have reported risk perception is more of a “distant introduction” that informs about the intentions (9). In the social cognitive theory (SCT) of Bandura, SE has a more powerful effect than OE on behavioral intentions (23). Self-efficacy has a greater effect on behavioral intention than outcome expectancies. This study had several limitations. First, generalization is limited by the fact that this sample was taken from Iranian women. Moreover, using self-report instrument mammography behavior could have been over-reported or under-reported. Further studies with adequate verification of the information reported in their design are recommended.

5.1. Conclusions

Overall, our findings support the validity and reliability of MBPS for assessing predictors of intentions and mammography behavior. In addition, a validation study with this list using a more objective measure of mammography behavior certainly further supports its psychometric properties in women.

This is the first major step in creating an effective intervention to improve mammography behavior in women 40 years and older.