1. Background

Cancer is a major worldwide public health problem and is considered the second leading death cause in children (1). The prevalence of pediatric cancer is estimated by the World Health Organization at approximately 100 per million children (2).

The incidence of this disease is higher in developed countries than in developing ones. According to 2012 statistics, approximately 19.3 per 100,000 children in East Africa suffer from pediatric cancer; however, 89.7 per 100,000 children in Western Europe suffer from pediatric cancer. Therefore, the incidence of this disease in developed societies other than Japan (more than 80 per 100,000 children) is higher than in developing societies (less than 40 per 100,000 children). But in recent years, the incidence of the disease has been increasing in developing countries (3).

The incidence of cancer among Iranian children varies in the geographical areas of the country; so, for girls and boys, it has been reported between 84 and 221 and 15 and 441 cases per million people, respectively (4).

The childhood cancer death rate has dropped steadily over the past 50 years. In about 80% of cancer cases in developed countries, where access to modern treatment and adequate supportive care is available, it can be successfully treated. However, only 10% of the world's children live in high-income countries, where there is extensive care (2).

Pediatric cancer accounts for 14.2 percent of the 23,300 deaths from cancer in Iranian children and makes it the number first cause of death rate (5).

Pediatric cancers are different from adult malignancies in terms of the type of cancer, the distribution, and the prognosis and they have a specific epidemiological pattern. Unlike adult cancers, most pediatric cancers are fatal without timely diagnosis and proper treatment. Also, there are no demographic screening programs or lifestyle risk reduction strategies that can be effective in improving pediatric cancer results (6).

Leukemia is the most common pediatric cancer, accounting for 28% of cases (including malignant tumors and borderline benign tumors), and brain tumors and the nervous system (about a quarter of which are malignant/borderline) account for 26% of cancers. Next, soft tissue sarcomas (7%), neuroblastoma (6%), non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, including, Burkitt's lymphoma (6%), kidney tumor (5%), and Hodgkin's lymphoma (3%) have their share in cancers (7, 8).

The pediatric cancer risk is increased due to genetic and prenatal factors (e.g., radiation, diethylstilbestrol) and postnatal factor (radiation, viruses), but in most pediatric cancer cases, the cause of cancer in children has remained unknown (9).

2. Objectives

This study aims at investigating the survival rate of pediatric cancer in demographic subgroups with different demographic, economic, social, and geographical conditions in Iran and comparing it with neighboring countries. In addition, the analysis was done, using parametric survival models. Then, a better fit was chosen as the final one.

3. Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of 1879 children with a definitive diagnosis of cancer admitted at Mahak Hospital and Rehabilitation Center (a hospital affiliated with non-governmental organizations for cancer treatment). A data gathering form was firstly designed by researchers for data collection. The included variables were age, sex, nationality, consanguinity of parents, treatment type, and experience in follow-up.

3.1. Participants

In this investigation, 1879 patients had cancers of leukemia, retinoblastoma, brain cancer, and sarcoma from 2007 to 2016. All children with these cancers with available records were included in the study.

3.2. Variables

Patients were divided into Iranian and non-Iranian (Afghan, Iraqi, Azerbaijani, Kuwaiti, Bahrein, Emirati, and Pakistani) groups. Patient’s age was considered < 1, 1 - 5, 6 - 10, 11 - 15, and > 15 years.

Methods of treatment (chemotherapy, chemotherapy + surgery, chemotherapy + surgery + radiotherapy, and other combinations of these treatments) were taken into account. Experiences in follow-up included loco-regional relapse, metastasis, and other experiences such as the experience of loco-regional relapse and metastasis together were considered. The main outcome was time from diagnosis to death or the last follow-up.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Continues and categorical clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients were reported in mean (standard deviation) and number (%), respectively. A chi-square test was used to compare the categorical characteristics of the patients between cancer groups. The median and interquartile range (IQR) survival time were reported. The effect of the nationality, age group (< 1, 1 - 5, 6 - 10, 11 - 15, > 15), sex, method of treatment (chemotherapy, chemotherapy + surgery, chemotherapy + surgery + radiotherapy, and other combinations of these treatments), consanguinity (parental relation) of patients, and experience in follow-up (loco-regional relapse, metastasis, and other such as second cancer or occurrence of metastasis and loco-regional relapse together) were assessed on survival. Parametric models including Gompertz, Weibull, lognormal, and log‑logistic models provided more accurate estimates if the correct shape was chosen. In this research, all the mentioned models were fitted after checking the corresponding assumptions (10). Models with minimum Akaike information criterion (AIC) were chosen for interpretations. A hazard ratio with a 95% confidence interval was reported. Significant effects in the univariable model (P < 0.2) were retained in the multiple models. However, clinically significant factors based on expert opinion were retained in the multiple models (11). The analysis was performed by R3.5.1. The significance level was set to 0.05.

3.4. Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the regional Ethics Committee of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The project code was IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1400.1033.

4. Results

A total of 1879 patients were included in the study as follows: 270 (14.37%) patients with retinoblastoma, 667 (35.5%) with leukemia cancer, 625 (33.26%) with a brain tumor, and 317 (16.87%) with sarcoma; 815 (43.37%) patients were female.

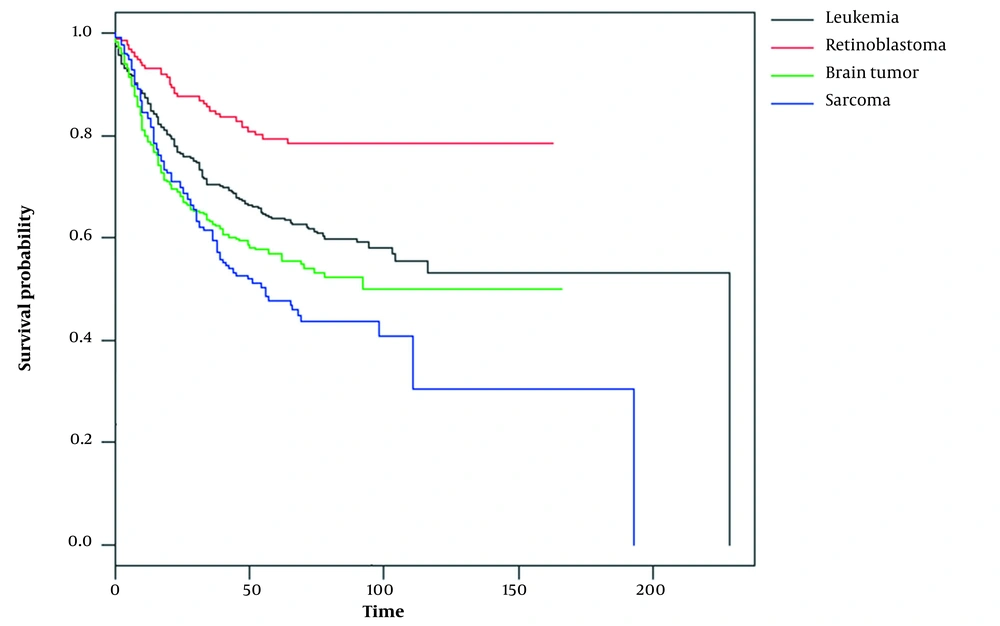

The median survival time (IQR) of the patients was 29.50 (6 - 70.5), 12 (6 - 46), 10 (5 - 45), and 17 (5 - 65) months for retinoblastoma, sarcoma, brain tumor, and leukemia, respectively. The number of deaths was 178 (26.7%) in leukemia patients, 37 (13.7%) in retinoblastoma patients, 174 (27.8%) in brain tumor patients, and 107 (33.8%) in sarcoma patients. Figure 1 shows the overall survival curve of the studied patients.

Table 1 shows that patient’s age, type of treatment, and experiences in follow-up were significantly different between cancer types. Table 2 illustrates that the Gompertz model has almost the minimum AIC in comparison to the other models. Then, further assessments are performed based on this model and presented in Table 3.

| Characteristics | Leukemia (n = 667) | Brain Tumor (n = 625) | Retinoblastoma (n = 270) | Sarcoma (n = 317) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years | < 0.001 b | ||||

| < 1 | 26 (3.9) | 37 (5.9) | 112 (41.5) | 13 (4.1) | |

| 1 - 5 | 314 (47.1) | 257 (41.1) | 150 (55.6) | 70 (22.1) | |

| 6 - 10 | 164 (24.6) | 209 (33.4) | 7 (2.6) | 96 (30.3) | |

| 11 - 15 | 143 (21.4) | 111 (17.8) | 0 | 121 (38.2) | |

| > 15 | 17 (2.5) | 7 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 15 (4.7) | |

| Nationality | 0.612 | ||||

| Iran | 611 (91.6) | 568 (90.9) | 242 (89.6) | 290 (91.5) | |

| Others | 55 (8.2) | 52 (8.3) | 28 (10.4) | 23 (7.3) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.8) | 0 | 4 (1.3) | |

| Sex | 0.959 | ||||

| Male | 379 (56.8) | 357 (57.1) | 149 (55.2) | 179 (56.5) | |

| Female | 288 (43.2) | 268 (42.9) | 121 (44.8) | 138 (43.5) | |

| Parental relation | 0.040 | ||||

| No | 464 (69.6) | 393 (62.9) | 170 (63) | 202 (63.7) | |

| Yes | 152 (22.8) | 182 (29.1) | 78 (28.9) | 79 (24.9) | |

| Missing | 51 (7.6) | 50 (8) | 22 (8.1) | 36 (11.4) | |

| Treatment | < 0.001 b | ||||

| Chemotherapy chemo + radio | 556 (83.4) 92 (13.8) | 59 (9.4) 0 | 147 (54.4) 0 | 40 (12.6) 0 | |

| Chemo + surg | 0 | 178 (28.5) | 111 (41.1) | 153 (48.3) | |

| Chemo + surg + radio | 0 | 285 (45.6) | 8 (3) | 113 (35.6) | |

| Others | 14 (2.1) | 96 (15.4) | 0 | 10 (3.2) | |

| Missing | 5 (0.7) | 7 (1.1) | 4 (1.5) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Experience in follow-up | < 0.001 b | ||||

| None | 521 (78.1) | 537 (85.9) | 186 (68.9) | 225 (71) | |

| Loco-regional relapse | 134 (20.1) | 67 (10.7) | 76 (28.1) | 34 (10.7) | |

| Metastasis | 12 (1.8) | 17 (2.7) | 8 (3) | 37 (11.7) | |

| Other | 0 | 4 (0.6) | 0 | 21 (6.6) |

Abbreviations: Chemo, chemotherapy; surg, surgery; radio, radiotherapy.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Significance at α = 0.05.

| Cancer Type | Models | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weibull (PH) | Gompertz (PH) | Lognormal (AFT) | Loglogistic | |

| Leukemia | 851.35 | 844.08 | 870.13 | 860.26 |

| Brain tumor | 870.20 | 846.21 | 836 | 838.01 |

| Retinoblastoma | 242.83 | 239.33 | 245.82 | 246.32 |

| Sarcoma | 425.13 | 425.51 | 427.34 | 428.60 |

Abbreviations: PH, proportional hazard; AFT, accelerated failure time.

| Factors | Leukemia | P | Brain Tumor | P | Retinoblastoma | P | Sarcoma | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | ||||||||

| Iran | ||||||||

| Others | 1.16 (0.60, 2.34) | 0.65 | 0.96 (0.46, 1.97) | 0.90 | 3.74 (1.38, 10.11) | 0.009 a | 0.81 (0.24, 2.75) | 0.73 |

| Age group (y) | ||||||||

| 1 - 5 | ||||||||

| < 1 | 7.63 (3.51, 16.60) | < 0.001 a | 0.78 (0.33, 1.87) | 0.58 | 1.06 (0.50, 2.26) | 0.88 | 1.02 (0.35, 2.99) | 0.97 |

| 6 - 10 | 1.25 (0.81, 1.92) | 0.31 | 1.11 (0.73, 1.68) | 0.63 | 1.42 (0.17, 11.75) | 0.74 | 0.30 (0.14, 0.63) | 0.001 a |

| 11 - 15 | 1.33 (0.87, 2.02) | 0.19 | 1.49 (0.93, 2.39) | 0.09 | - | - | 0.99 (0.58, 1.70) | 0.99 |

| > 15 | 1.37 (0.42, 4.45) | 0.60 | 2.15 (0.62, 7.47) | 0.23 | - | - | 0.69 (0.22, 2.13) | 0.52 |

| Sex (male) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.35) | 0.76 | 1.13 (0.79, 1.61) | 0.50 | 0.66 (0.32, 1.37) | 0.27 | 1.16 (0.74, 1.82) | 0.51 |

| Parental relation (yes) | 1.56 (1.08, 2.24) | 0.02 a | 1.18 (0.81, 1.73) | 0.39 | 1.42 (0.62, 3.27) | 0.40 | 1.80 (1.11, 2.92) | 0.02 a |

| treatment | ||||||||

| Chemo | ||||||||

| Chemo + radio | 0.89 (0.59, 1.36) | 0.60 | ||||||

| Chemo + surg | - | - | 1.07 (0.56, 2.05) | 0.83 | 0.47 (0.21, 1.02) | 0.06 | 0.36 (0.15, 0.89) | 0.03 a |

| Chemo + surg + radio | - | - | 0.64 (0.34, 1.22) | 0.18 | - | - | 0.28 (0.11, 0.69) | 0.006 a |

| Others | 0.56 (0.13, 2.33) | 0.42 | 1.28 (0.61, 2.65) | 0.51 | 0.60 (0.07, 4.63) | 0.62 | 0.38 (0.09, 1.64) | 0.19 |

| Experience in follow-up | ||||||||

| None | ||||||||

| Loco-regional relapse | 4.61 (3.20, 6.64) | < 0.001* *** | 2.40 (1.58, 3.64) | < 0.001 a | 1.34 (0.62, 2.89) | 0.45 | 1.00 (0.49, 2.07) | 0.99 |

| Metastasis | - | - | 3.71 (1.71, 8.06) | 0.001 a | - | - | 3.80 (2.16, 6.69) | < 0.001 a |

| Others | 0.98 (0.24, 4.08) | 0.98 | 2.62 (0.79, 8.70) | 0.11 | 5.75 (1.46, 22.72) | 0.01 a | 2.85 (1.51, 5.38) | 0.001 a |

Abbreviations: Chemo, chemotherapy; surg, surgery; radio, radiotherapy; CI, confidence interval.

a Significance at α = 0.05.

4.1. Leukemia Patients

The patient with an age < 1 year had a mortality risk of 7.63 (3.51, 16.60) times more than the patients, who were 1 to 5 years (P < 0.001). The patients who had parental relations had a higher mortality hazard than the patients, who did not have parental relations (1.56 (1.08, 2.24), P = 0.02).

In addition, the patients with experience of loco-regional relapse had a mortality hazard of 4.61 (3.20, 6.64) times more than the patients, who did not experience relapse or metastasis as well as others during follow-up (P < 0.001), whereas the mortality hazard of the patient who had chemotherapy plus radiotherapy was lower than the patients who had chemotherapy alone (0.89 (0.59, 1.36), P = 0.60).

4.2. Retinoblastoma Patients

Mortality risk in other nationality patients was significantly higher than in Iranian patients (3.74 (1.38, 10.11), P = 0.009). The patients, who experienced metastasis or metastasis plus loco-regional relapse had a higher mortality risk than the patient who did not experience any particular conditions (5.75 (1.46, 22.72), P = 0.01). In addition, the patients, who were treated with both chemotherapy and surgery, had lower mortality than the patients, who were treated with chemotherapy (0.47 (0.21, 1.02), P = 0.06).

4.3. Brain Tumor Patients

The patients, who experienced recurrence during follow-up, had a significantly higher risk of death compared to the other patients (P < 0.001). The patients with the experience of either loco-regional relapse or metastasis had significantly higher mortality in comparison to those who experienced none of them (P = 0.001).

4.4. Sarcoma Patients

The patients, who were aged 5 to 10 years, had significantly lower mortality than the patients aged 1 to 5 years (0.30 (0.14, 0.63), P = 0.001). History of parental relation was significantly associated with higher mortality risk (Table 1). Patient treatment including chemotherapy and surgery and radiotherapy significantly decreased the risk of mortality (0.28 (0.11, 0.69), P = 0.006). Experience of metastasis was associated with a higher risk of death (3.80 (2.16, 6.69), P < 0.001).

5. Discussion

The survival rate of children with cancer was affected by many factors such as the type, level, and histology of the child's cancer, age, gender and race, and his/her primary health condition and access to health care, insurance coverage, and follow-up after initial treatment. This study determined the importance of survival-related factors (12, 13).

In this study, the death risk from leukemia for children with the age under 1 year old was 7.6 times higher than the children older than 1 year old. Other studies revealed that the 5-year survival rate of children's leukemia has significantly increased by 83.7% from 1990 to 1994 and by 90.4% from 2000 to 2005 in all age groups except infants under 1 year old (14) and with aging, the survival rate of children with cancer increases (15, 16).

Proper cancer treatment is an important determining factor in the long-term survival of children after infection. Due to the aggressive nature of most pediatric cancers, the use of combination therapies, variety in using chemotherapy drugs, the addition of radiotherapy, and other alternative therapies such as immunotherapy to the treatment process in most pediatric cancers can increase the survival of infected children (17).

According to the results of this study, combination therapy more than chemotherapy increases the survival time itself, and studies over time show that with the advancement of treatment techniques and the addition of treatment approaches, the survival of children with cancer has increased over time (14, 18, 19). On the other hand, an important point to consider is the long-term effects of more aggressive treatment in these children (20, 21).

Advances in pediatric oncology have not only improved survival but also reduced the long-term effects of the disease by adopting a risk-based treatment approach (22). This approach has led to a change in treatment and care standards for fatal pediatric cancers, including nervous system tumors, leukemia, and sarcoma. The risk-adjusted approach allows treatment to be intensified in the high-risk group, while in the low-risk group, the toxicity deficiency and delay (tardive) effects can be minimized without compromising survival (23).

According to the results of this study, local recurrence of cancer metastasis is one of the risk factors with a high-risk ratio in reducing patient survival in these cancers. Recurrence is still the leading cause of failure in acute myeloid leukemia in children (24). In the study of Teachey and Hunger, cancer recurrence in children with ALL has improved greatly due to a more accurate classification of risk, intensification of treatment, and a better understanding of the whole biology (25).

Also, patients with leukemia and sarcoma who had a familial relationship had a higher death risk ratio than patients, who did not have a familial relationship. A wide variety of cancers in children are familial (26).

It is well established that genetic components are involved in increasing the risk of developing leukemia. For this reason, the familial relationship of parents increases the children's homozygosity and increases the risk of cancer (27). Mehrvar et al. reported that 41% of parents of children with leukemia had a familial relationship (28) and Bener et al.’s study showed the rate of leukemia and lymphoma in children of parents with a familial relationship was higher than in the unrelated group (29).

It is important to have periodic and regular care of children with family risks, such as familial relationships of parents or a family history of cancer for early diagnosis and initiation of life-saving treatments. Also, genetic counseling in families with genome-related cancers today is promising for identifying the family cancer genome and taking further care towards practical implications (30, 31).

Mahak Hospital is a cancer center with patient admissions from all over Iran. And the results of this study can probably be generalized to Iranian children.

The study was limited in the number of non-Iranians compared to Iranians and the outcome in patients because in some cases, the outcome was not clear and we had to call again.

Survival analysis using a parametric approach, which is used for data analysis in this study, could be a strong point because these models result in a more precise estimation than the semi-parametric models if the function was selected appropriately (31). In addition, all the possible parametric models were fitted to the data and, then, the Gompertz model as the better fit was finally chosen. It is suggested that other cancers be studied by parametric model fitness in future studies (32, 33).

5.1. Conclusions

The most important factors affecting the survival of children with common cancers of leukemia, retinoblastoma, brain tumors, and sarcoma were age > 1 year for leukemia, 5 to 10 years for sarcoma, parental familial relationships (sarcoma and leukemia), combination therapy (leukemia, retinoblastoma, and sarcoma), and local recurrence and metastasis of primary cancer using Gompertz model. Further studies on the possibility of designing and implementing periodic care in children with risk factors for cancer are needed.