1. Context

Cancer is the fourth leading cause of death in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), and its prevalence is expected to increase significantly by 2030 (1). Although early cancer diagnosis has improved in certain countries within the region, many patients in most countries still receive diagnoses at advanced stages of the disease (2). Consequently, palliative care (PC) becomes the only available option for these patients, however, due to the underdevelopment of PC services in the region, many patients’ PC needs remain unmet (3).

Access to PC services is now a fundamental right for all individuals suffering from life-threatening illnesses. The World Health Organization (WHO) has strongly recommended that all countries prioritize PC within their public health programs, integrate PC services within their healthcare systems and establish comprehensive policies and systematic frameworks for its effective implementation (4).

Palliative care is out of reach for most people who need in the EMR which consists of 22 countries with widely diverse cultures, health systems, and resources. The region includes both high-income, oil-rich countries, where PC is available in the larger cities, and low-income countries, where political instability, conflict and forced migration make it difficult to provide any kind of health care (5). Compared with the other five WHO regions, PC services in the EMR are far less developed. Palliative care is not yet mainstreamed in any country in the EMR, and only four countries provide it as an isolated service (6). Data are therefore urgently needed for guidance on how PC can be integrated into local health systems (7, 8).

Many eastern Meditranian region countries (EMRCs) have adopted the WHO recommendation gradually, taking into account their available resources, workforce, and healthcare system. For instance, PC can exist as an independent program, be integrated into national health programs, or serve as a component of cancer control initiatives (9). By identifying existing PC policies across the region, it is possible to gain insights into developing effective PC delivery systems (10). Analyzing policies allows to precisely examine problem definitions, policy compilation and implementation, resource allocation, and the dimensions influencing the policy-making process. Furthermore, studying existing policies establishes a common language for stakeholders and provides a platform for operationalizing developed programs and implementing necessary interventions to enhance evaluation indicators (11).

In addition, reviewing PC policies was introduced as one of the four main components of the WHO PC strategy in 2007. Considering that EMR has made efforts to establish and develop PC in recent years, coordinated data collection provides a clearer picture of needs, challenges, and barriers at the regional level (12). Therefore, regular review and analysis of health policies are necessary to understand the success and failure of policies adopted in the past and plan for the future (13).

In this regard, scoping reviews are becoming an increasingly common approach to synthesize evidence, and are very popular with end users (14). Scoping reviews can be used to provide an overview of either broad or focused areas of research and policy, to frame research and policy programs, to highlight gaps in knowledge and identify areas for further evidence syntheses (15).

Given the need to identify PC policies in the region and account for country-specific differences, the study aimed to comprehensively explore and synthesize existing literature on policy analysis related to PC within the EMR, identifying key themes, gaps, and potential areas for improvement.

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

A scoping review was conducted following the methodological guidance of Arksey and O’Malley to analyze PC policies in the EMR. It is an influential framework for conducting scoping reviews which was originally proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (2005) (16). Their framework was strengthened by the work of Levac et al. (2010), which was more explicit about the stages of the review (17). Both frameworks helped develop JBI's approach to conduct scoping reviews (18). The Arksey and O'Malley (as cited by Xue et al.) framework was selected because it was the most frequently cited framework for conducting a scoping review (19).

The Preferred Reporting Items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses exten-sion guidelines for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) were followed in reporting this review (20). The study lasted approximately ten months. It was conducted from 3 November 2023 to 16 January 2024.

2.2. Study Framework

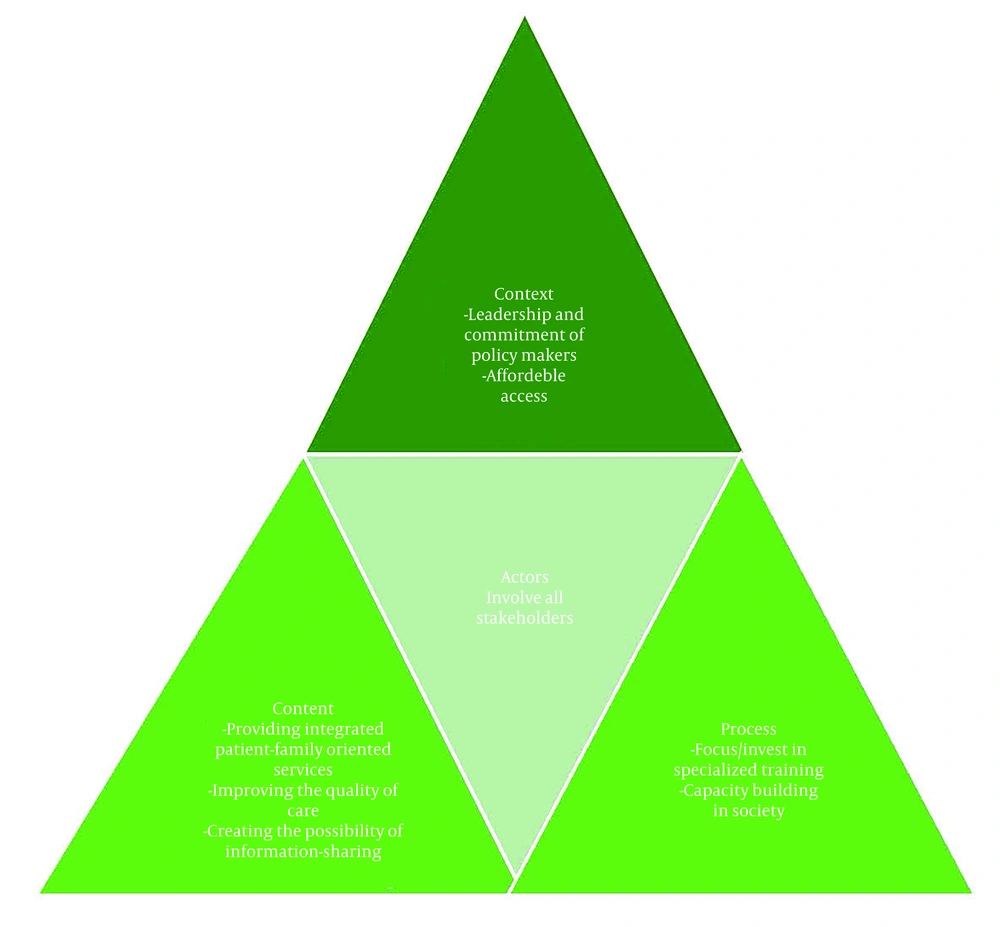

The Walt and Gilson’s policy triangle framework was adopted as a framework for analyzing and summarizing findings. This model is specifically designed for health sector policy analysis, encompassing four key components: Context, content, process, and actors. By examining these dimensions together, gaining insights into how policies are shaped and implemented will be possible. The framework, particularly recommended for using in developing countries, helps evaluate problems and identify solutions (21).

2.3. Information Source and Search Strategy

Searches were performed on the following electronic databases: Scopus, Medline, Embase, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and ProQuest. The search terms that were used to guide the process were as follows: ‘palliative care’, ‘terminal’, OR ‘hospice’, OR ’end of life’, OR ‘supportive medicine’, OR ‘palliative’ AND’Middle East’, OR ‘Afghanistan’, OR ‘Bahrain’, OR ‘Iran’, OR ‘Iraq, OR ‘Jordan’, OR ‘Kuwait’, OR ‘Lebanon’, OR ‘Oman’, OR ‘Qatar’, OR ‘Saudi Arabia’, OR ‘Syria’, OR ‘Palestine’, OR ‘Yemen’, OR ‘Egypt’, OR ‘Cyprus’, OR ‘United Arab Emirates’. Notably, any time limit on the search wasn’t considered to maximize access to relevant literature. The searches included titles, abstracts, and full-text of English articles. The reference lists of the identified papers were also hand-searched for potential papers (Table 1).

| No. | Search Strategy |

|---|---|

| 1 | (“Palliative Nursing”[tiab] OR “palliative care”[tiab] OR (care[tiab] AND Palliative[tiab]) OR “palliative treatment”[tiab] OR (palliative[tiab] AND treatment[tiab]) OR “palliative therapy”[tiab] OR (palliative[tiab] AND treatment[tiab]) OR “palliative surgery”[tiab] OR (palliative[tiab] AND surgery[tiab]) OR “Palliative Supportive Care”[tiab] OR (Palliative[tiab] AND “Supportive Care”[tiab]) OR “Palliative Care Nursing”[tiab] OR “Hospice Nursing”[tiab] OR (Nursing*[tiab] AND Hospice[tiab]) OR “Bereavement Care”[tiab] OR (Bereavement[tiab] AND Care[tiab]) OR “hospice care”[tiab] OR (hospice[tiab] AND care[tiab]) OR “end-of-life care”[tiab] OR “terminal care”[tiab] OR (terminal[tiab] AND care[tiab]) OR “life care end”[tiab] OR (“care end”[tiab] AND life[tiab])) |

| 2 | (“Middle East”[tiab] OR “Afghanistan”[tiab] OR “Bahrain”[tiab] OR “Iran”[tiab] OR “Iraq”[tiab] OR “Jordan”[tiab] OR “Kuwait”[tiab] OR “Lebanon”[tiab] OR “Oman’[tiab] OR “Qatar”[tiab] OR “Saudi Arabia”[tiab] OR “Syria’[tiab] OR “Palestine’[tiab] OR “Yemen”[tiab] OR “Egypt”[tiab] OR “Cyprus’[tiab] OR “United Arab Emirates[tiab]”) |

| 3 | 1 AND 2 |

Search Strategy Used in PubMed/MEDLINE

2.4. Study Selection

All papers retrieved from the database searches were exported to EndNote software, after which duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening were carried out by the authors (S.B and H.A) to identify relevant studies. Full-text versions of the relevant studies were retrieved. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Documents related to PC in the EMR, including articles, meeting minutes, laws, regulations, bylaws, circulars, guidelines, approvals, programs, reports, news articles, and statements from meetings and speeches; (2) all materials must be reported in English; and (3) there were no time restrictions on the documents. The study selection process is illustrated using a PRISMA-ScR flowchart.

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

A narrative synthesis was carried out using Walt and Gilson’s policy framework an analytical and organizing framework. researchers S.B. and H.A. independently extracted relevant data as codes which were organized following Walt and Gilson’s policy four constructs: Context, content, process, and actors. Key findings were further reviewed by other members of the research team. A summary of the findings is presented in the results section.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

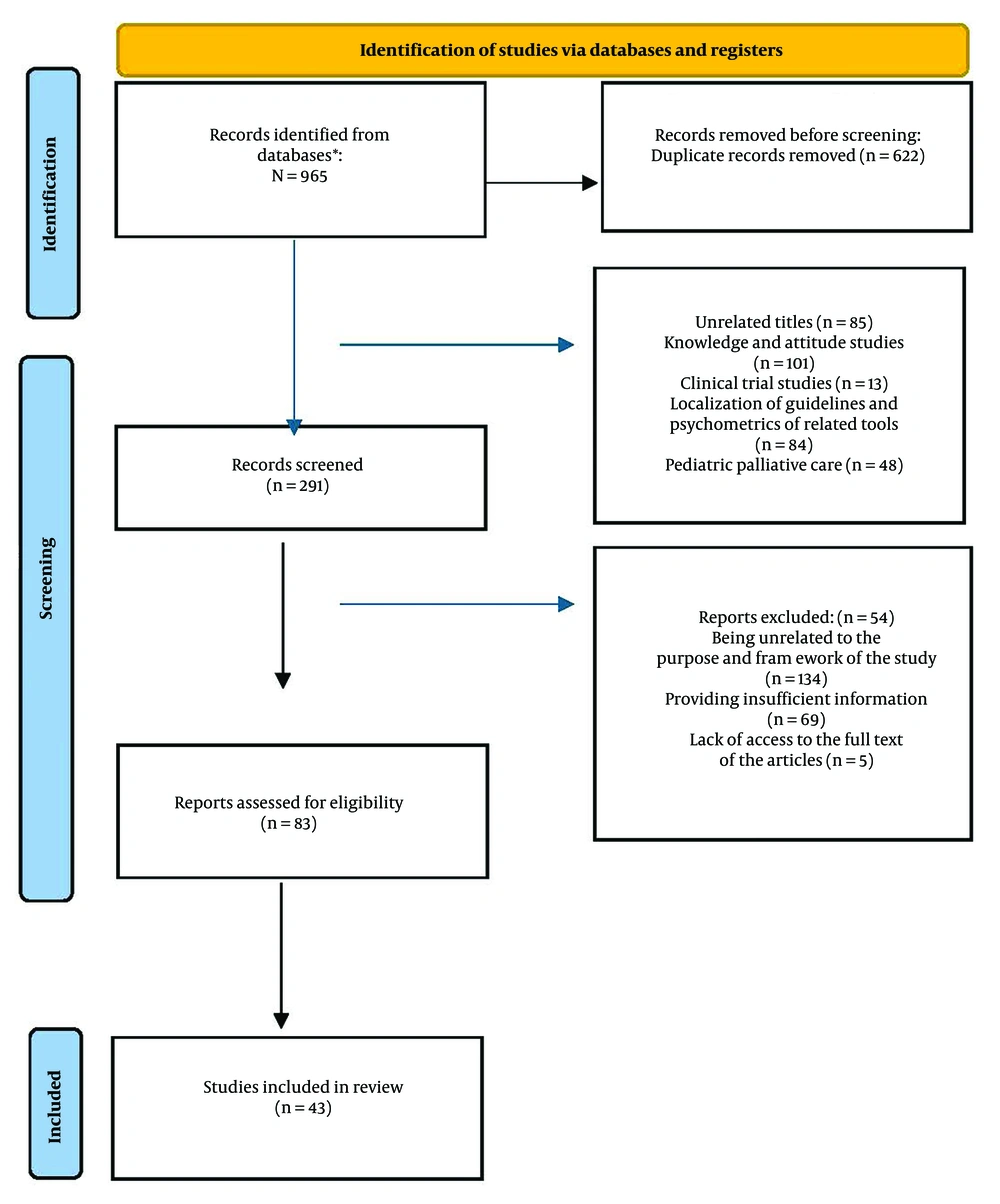

A comprehensive review process was undertaken, resulting in the identification of 965 papers. After eliminating duplicate titles, 622 papers remained, comprising 876 journal articles, 37 conference abstracts, 27 book chapters, 9 graduate theses, and 10 government documents. These papers were assessed based on their titles and abstracts. Studies focusing on the knowledge and attitudes of PC providers, psychological tools, cross-cultural validation of guidelines, and pediatric PC were excluded. Subsequently, the remaining 291 papers underwent full-text evaluation. A meticulous assessment of the articles led to the exclusion of 208 cases, including studies with repetitive findings, limited access to full-text content, insufficient information, and incompatibility with the analytical framework. Finally, 43 papers were used for analysis (10, 22-63). Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA flowchart detailing the texts reviewed in this study. Additional details about the included documents are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

| No. | Authors; Year | Title | Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Beiranvand et al., 2022 (22) | Hospice care delivery system requirements | Qualitative |

| 2 | Hojjat-Assari et al., 2022 (23) | Explaining health care providers’ perceptions about the integration of palliative care with primary health care; a qualitative study | Qualitative |

| 3 | Sanchez-Cardenas et al., 2022 (24) | Region-specific macro indicators on palliative care development in the Eastern Mediterranean region: A Delphi study | Qualitative (Delphi) |

| 4 | Beiranvand et al., 2022 (25) | Developing a model for the establishment of the hospice care delivery system for Iranian adult patients with cancer | Mixed method |

| 5 | Fereidouni et al., 2022 (26) | Preferred place of death and end-of-life care for adult cancer patients in Iran: A cross sectional study | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 6 | Amroud et al., 2021 (27) | A comparative study of the status of supportive-palliative care provision in Iran and selected countries: Strengths and weaknesses. | Comparative |

| 7 | Hojjat-Assari et al., 2021 (28) | Developing an integrated model of community-based palliative care into the primary health care (PHC) for terminally ill cancer patients in Iran | Mixed |

| 8 | Brant et al., 2021 (29) | Palliative care nursing development in the Middle East and Northeast Africa: Lessons from Oman. | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 9 | Zarea et al., 2020 (30) | Comparison of the hospice palliative care delivery systems in Iran and selected countries | Comparative |

| 10 | Barasteh et al., 2022 (31) | Palliative care in the health system of Iran: A review of the present status and the future challenges | Qualitative |

| 11 | Eltaybani et al., 2020 (32) | Palliative and end-of-life care in Egypt: Overview and recommendations for improvement | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 12 | Brant et al., 2019 (33) | Global survey of the roles, satisfaction, and barriers of home health care nurses on the provision of palliative care | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 13 | Ansari et al., 2019 (34) | Process challenges in palliative care for cancer patients: A qualitative study | Qualitative |

| 14 | Alshammary et al., 2019 (35) | Development of palliative and end of life care: The current situation in Saudi Arabia | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 15 | Ansari et al., 2018 (10) | Palliative care policy analysis in Iran: A conceptual model | Qualitative |

| 16 | Hablas, 2017 (36) | Palliative care in Egypt: The experience of the Gharbiah Cancer Society | Retrospective analysis of registered data |

| 17 | Khoshnazar et al., 2016 (37) | Structural challenges of providing palliative care for patients with breast cancer | Qualitative |

| 18 | Rassouli and Sajjadi, 2016 (38) | Palliative care in Iran: Moving toward the development of palliative care for cancer | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 19 | Shamieh and Hui, 2015 (39) | A comprehensive palliative care program at a tertiary cancer center in Jordan | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 20 | Osman, 2015 (40) | Development of palliative care in Lebanon: Obstacles and opportunities | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 21 | Daher et al., 2013 (41) | Integrating palliative care into health education in Lebanon | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 22 | Bushnaq and Fadi Abusuqair, 2012 (42) | Jordan palliative care and pain initiative 2011: Building capacity for palliative care programs in public hospitals; progress in palliative care | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 23 | Malas, 2011 (43) | The current status of palliative care in Cyprus: Has it improved in the last years? | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 24 | Shawawra and Khleif, 2011 (44) | Palliative care situation in Palestinian authority | Quantitative (descriptive) |

| 25 | Shamieh et al., 2010 (45) | Modification and implementation of NCCN Guidelines™ on palliative care in the Middle East and North Africa Region | Quantitative (descriptive) |

Original Articles

| No. | Authors; Year | Title | Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ashrafizadeh and Rassouli, 2023 (46) | Addressing health disparities: Palliative care for migrants and refugees in the Eastern Mediterranean Region | Commentary |

| 2 | Krakauer et al., 2023 (47) | Palliative care need in the Eastern Mediterranean Region and human resource requirements for effective response | Secondary data analysis |

| 3 | Fereidouni et al., 2023 (48) | Preferred place of death challenges the allocation of health resources in Iran | Comment |

| 4 | Silbermann, 2023 (49) | Middle East Cancer consortium-development of palliative care services for cancer patients | Review |

| 5 | Osman et al., 2022 (50) | Palliative care in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: An overview | Report |

| 6 | Krakauer et al., 2022 (51) | Palliative care models and innovations in 4 Eastern Mediterranean Region countries: A case-based study | Report |

| 7 | Fereidouni et al., 2021 (52) | Preferred place of death in adult cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis | Review |

| 8 | Barasteh et al., 2021 (53) | Integration of palliative care into the primary health care of Iran: A document analysis. | Document |

| 9 | Hablas, 2021 (54) | The critical contribution of an NGO to the development of palliative care services in the community–encouraging outcome of the tanta project in Egypt | Book section |

| 10 | Nijhawan and Al-Shamsi, 2021 (55) | Palliative care in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) | Book section |

| 11 | Shamieh et al., 2020 (56) | Gaining palliative medicine subspecialty recognition and fellowship accreditation in Jordan | Document analysis |

| 12 | Fadhil and Ghali, 2019 (57) | Research in palliative care in Iraq: Humble steps | Book section |

| 13 | Abu Saad Huijer et al., 2016 (58) | Palliative care for older adults: State of the art in Lebanon | Review |

| 14 | Hajjar et al., 2015 (59) | International palliative care: Middle East experience as a model for global palliative care | Review |

| 15 | Al-Zadjali and Al-Sinawi, 2016 (60) | Palliative care nursing in Oman: A country's Journey | Review |

| 16 | Qadire et al., 2014 (61) | Palliative care in Jordan: Accomplishments and challenges | Book section |

| 17 | Zeinah et al., 2013 (62) | Middle East experience in palliative care | Review |

| 18 | Hablas, 2011 (63) | Palliative care in Egypt: Challenges and opportunities | Document analysis |

Scholarly Perspective Articles

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Out of the 43 papers included in this study, 38 (88.37%) articles were journal articles (10, 22-45), one (2.32%) conference abstract (36), and four (9.30%) book chapters (54, 55, 57, 61). The studies covered countries such as Egypt (32, 36, 54, 63), Jordan (39, 42, 56, 61), Saudi Arabia (35), Lebanon (40, 41, 58), Cyprus (43), Oman (29, 60), United Arab Emirates (55), Palestine (44), and Iran (10, 22, 23, 25-28, 30, 31, 34, 37, 38, 46, 48, 52, 53). Additionally, other studies investigated countries in the Mediterranean region more broadly (24, 39, 47, 49-51, 59, 62), including Qatar, Kuwait, Pakistan, Iraq, and Syria. All studies were in English and were mostly published between 2010 and 2023 (Tables 2 and 3). The subclasses were extracted based on Walt and Gilson's policy triangle framework (Figure 2).

3.3. The Context

Context refers to a set of systematic political, economic, social, and international factors that influence policy-making (64). In this section, we explored the intricate ecosystem that impacts policy discussions and decisions in the field of palliative care. Regarding the policies adopted by EMRCs to establish PC for cancer, they can be categorized into two main areas.

3.3.1. Leadership and Commitment of Policymakers

One of the most important and perhaps earliest actions of EMRCs has been informing policymakers (10, 24, 27, 29, 31, 33, 34, 42) to gain their support (10, 27, 29, 30, 33, 42, 56, 62). Additionally, many countries in the region have mandated the government and the MOH to establish a PC system (10, 24, 27, 29, 33, 53, 56, 62) and to determine and communicate general policies in this field (22, 29, 33, 35, 38, 56, 62). However, only a limited number of EMRCs have developed a comprehensive national (regional) strategy (program) to provide PC (35, 41, 44, 49, 56). For example, Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia are actively implementing these strategies and evaluating them periodically. In Egypt, Morocco, and Pakistan, referral to receive PC is part of national cancer strategies. Some countries have designated specific individuals or committees responsible for managing and following up on PC programs within MOH or similar organizations (24, 32, 54).

Official agreements at the national and international levels (24, 29, 31, 33, 38, 41) and support from international organizations, including WHO (25, 29, 33, 38, 41, 65), aim to create the necessary platform for the establishment and development of cancer PC systems in EMRCs.

3.3.2. Affordable Access

This sub-category primarily pertains to the financing of services, including specific budget allocations and insurance coverage, as well as the provision of essential resources such as human personnel, physical space, and equipment.

Financial resources for providing PC in EMRCs are secured in three ways: Through government allocations and subsidies (27, 35), insurance coverage and direct out-of-pocket payments (24, 27, 35, 55), or primarily through charity organizations (10, 27, 28, 30, 31, 34, 36, 37, 44, 53, 54, 56, 63). Countries such as Palestine and Morocco have not allocated any budget to PC services (24).

Developing service packages for the insured is another financial policy adopted by EMRCs, which has led to better access to these services in some countries. It is also important to note that these services generally began in public hospitals due to greater accessibility (27, 28, 35, 38, 61).

Efforts to provide other resources, such as human resources, equipment, and medicine are essential measures in the development of the PC delivery system in the studied countries. Studies have shown that despite the translation and use of WHO pain relief guidelines and lists in most EMR countries, pain management and access to opioids remain major challenges. For example, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Palestine have reported access to both oral and injectable morphine, while in Iran, only the injectable type of morphine is available. Additionally, there are significant differences in the regulations related to the preparation and administration of these drugs in EMRCs (49, 50).

3.4. The Content

Content encompasses the goals and planned actions that lead to policy outcomes (64). In this section, we examine the political and operational goals, as well as the laws, regulations, and guidelines related to the establishment of PC. The review of selected studies reveals that the policies adopted by EMR countries can be categorized into three main areas:

3.4.1. Providing Integrated Patient-Family-Oriented Services

The starting point for providing PC services in EMRCs is mainly in specialized and sub-specialized hospitals (23, 28, 29, 33, 35, 38, 42, 43, 55, 61, 62) and in connection with cancer care and treatment, often as part of cancer control programs (24, 27, 28, 30, 38, 39, 41, 42, 53, 62). In some cases, these services originated from pain relief clinics or hospices (36, 43, 44, 54, 62, 63). The role of private, charity, and NGO centers (24, 27, 28, 30, 31, 36-38, 43, 54, 55, 63) is also prominent in the initial provision of services in these countries.

The most important activities of EMRCs in this area include the leveling of services (29, 33, 45, 62) and their integration at all levels of the health system, especially at the PHC level (29, 33, 35, 62), as well as strengthening the referral system (35, 45). Subsequently, to provide diverse and integrated services, structures such as clinics, hospices, long-term care (LTC) facilities, home care centers, and specialized counseling teams have been developed (24, 27, 36, 39, 45, 54, 62, 63). This approach ensures 24/7 access through telephone consultations and home care teams, in addition to providing services in other fields (28, 35, 39, 41, 43, 44, 55, 62).

Providing equipment to families for home care (27, 28, 36, 39, 43, 54, 55, 62, 63), emphasizing community-level care for maximum access (33, 51), and educating, supporting, and empowering family caregivers (26, 59-61, 66) are the main components of cancer PC services in the studied countries.

3.4.2. Improving Quality of Care

In the PC delivery systems of EMRCs, a wide range of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual PC services are provided to patients, families, and professional caregivers (24, 27, 28, 35, 36, 44, 46, 54, 61, 63). To improve the quality of care, measures such as developing or revising care standards (32, 39, 45, 58), designing standardized localized clinical or educational guidelines (24, 30, 38, 39, 45, 58), and creating a monitoring, evaluation, and control system (24, 29, 33, 35, 43, 56) are implemented to assess the quality of care and services provided (20, 24, 34, 47). Additionally, the formation of specialized PC teams (35, 41, 43, 55) and defining the tasks, responsibilities, and authority limits (27, 49) are crucial for delivering quality care. However, the participation of patients, families, and care providers in decision-making for planning PC programs has been less emphasized (35, 42, 55, 56).

3.4.3. Creating Information-Sharing Possibilities

The existence of an electronic documentation system (35, 36, 54, 63) for the coordinated recording of data and the creation of national information networks (22, 31, 35, 38, 47, 51, 53), as well as providing access to international information networks (35, 47, 51), is essential for informing about all activities related to PC. The promotion of research, establishment of specialized journals, and research centers (22, 25, 29, 31-33, 38, 39, 45, 46, 53, 57-60) are also common measures in all the studied countries.

3.5. The Process

The process includes all the actions and activities during policy implementation and refers to how policies are initiated, developed, formulated, negotiated, communicated, implemented, and evaluated. It can follow a top-down approach (which requires fundamental changes in the role of the state) or a bottom-up approach [which does not question the status quo (64)]. The review of selected studies has shown that in EMRCs, efforts to establish and develop cancer PC services primarily focused on two categories:

3.5.1. Specialized Training

Considering that specialized human resources are the core of the PC system and that providing this type of care is impossible without special attention to them, one of the most important initial steps taken in EMRCs to develop the PC system has been the specialized training of human resources. This process is mainly conducted through in-service training programs for all members of the team and, to a lesser extent, through academic training at different stages (10, 29-34, 36, 38, 41, 42, 45, 46, 53-56, 58-63). These trainings combine face-to-face and non-face-to-face methods (29, 31, 33, 38, 41, 44, 45, 58-62) and theoretical and practical components (29, 33, 35, 39, 41, 45, 58-62), based on appropriate and up-to-date educational content (31, 34, 37, 44, 50). The use of international experiences in establishing service centers and training specialized human resources is evident (23, 26, 28, 29, 33, 36, 41, 48, 52, 54, 63).

Holding scientific congresses, conferences, meetings, and workshops (10, 35, 37, 38, 41, 49, 62) and forming scientific and specialized associations and groups (38, 41, 43, 51, 56, 62) are also among the actions taken by EMRCs to train, support, and empower professional caregivers. However, the challenge of providing adequately trained specialists still exists.

3.5.2. Capacity Building in Society

One of the most important activities of EMRCs in establishing and developing PC is designing and implementing programs that aim to enhance general knowledge and promote gradual cultural acceptance among specialists, healthcare providers, and the general public (35, 41, 43, 55, 58). Creating a PC/hospice day in the annual calendar (40, 47, 50), holding related events and celebrations (24, 36, 40), and establishing hospices and LTCs to foster better acceptance by patients and their families (41, 55) are among these actions.

3.6. The Actors

Actors comprise individuals, groups, or organizations involved in the policy reform process who are effective participants in policymaking and the formation of political networks to address specific issues (64). Based on the findings from this study, in EMRCs, the key actors were; the government (including government institutions and organizations, with the MOH at the top) (22-25, 37, 38, 56); private, charity, and non-governmental organizations (24, 26, 49, 50, 52, 56); international organizations (such as WHO, IHPCA, etc.) (24, 51, 56); family caregivers and patient family members (35, 40, 49-51, 56); specialist care teams (35, 49, 50, 56); national and international peer groups (41, 43, 62, 63); and volunteers (10, 24, 47, 49, 50, 62).

4. Discussion

World Health Organization has recognized PC as a fundamental component of cancer control. It aims to manage symptoms, reduce treatment-related complications, and primarily improve the quality of life for individuals with life-threatening diseases, including cancer (12). World Health Organization has also advised all countries to prioritize PC in their public health programs and to establish appropriate policies and systematic frameworks for implementing these services (65). Additionally, WHO emphasizes the importance of analyzing PC policies at national and regional levels, including in the EMR, to identify gaps and challenges, set priorities, highlight successful programs as models, and determine the most effective interventions for further development (3).

This study aimed at discussing the policies related to providing PC services in EMRCs, utilizing Walt and Gilson’s policy analysis framework, focusing on the four components: Context, content, process, and actors.

By using this framework, a clear picture of the policy-making process in the field of cancer PC design and development in EMRCs was obtained. The results of this study have led to the identification of the effective context in cancer PC policymaking in EMRCs, the content of the policies adopted, the policymaking process, and the stakeholders involved.

Based on the obtained results, the leadership and commitment of policymakers and decision-makers in each health system are crucial for the development of PC. Their involvement helps create the necessary conditions for the launch and expansion of these services. Government and healthcare provider support for palliative and end-of-life care programs in cancer has facilitated the establishment and growth of integrated services at the community level. Additionally, it is essential to formulate and develop a national PC program for cancer, alongside other health programs (67, 68).

However, without financial support, patients with cancer will not be able to access PC (65). Providing financial resources has always been a significant challenge in delivering these services across different societies. In addition to government funding, insurance organizations and non-governmental charitable organizations can help address this issue. Designing service packages for the insured and allocating subsidies to them is also an effective financial policy that can improve access to these services. Although establishing and providing this type of care require financial investment, it can ultimately lead to savings in healthcare costs for this patient group (66).

Access to essential drugs, especially opioids, for managing pain in patients with cancer is a crucial indicator, considering complications and cultural issues (69). Factors such as fear of addiction, restrictive drug prescription laws, and the low knowledge and attitudes of service providers are significant barriers to pain control in EMRCs (70). To overcome these obstacles, public and professional training, amending laws, and facilitating access to drugs can be effective.

The analysis of policies adopted in EMRCs showed that PC services in the reviewed countries have expanded to all levels and care areas (including hospital, home, and community). These services encompass a wide range of care and support in physical, psychological, spiritual, social, and bereavement dimensions, provided to patients and their families. The extent of these services varies depending on the development level of the PC system in different countries (9, 71). Community-based care, utilizing capacities such as family and home care by family members, and establishing structures like hospices and nursing centers can be considered in health policies.

Furthermore, integrating PC services at all levels of the health system, especially at the PHC level, and connecting them with other care areas is particularly important. This integration ensures access to both general and specialized services and continuity of care. According to the Millennium Development Goals (4, 65), integrating PC into primary care and public health is essential. Since most of these services can be provided at the first level and are not specialized or complex, this can significantly reduce the use of hospital resources and patient hospitalization for incurable diseases. Establishing a basic national information registration system, equipping care providers with an electronic file system, and implementing strategies such as family doctors, a referral system, and service leveling, along with standardized guidelines and instructions, will help integrate and coordinate care (65, 72).

The fundamental pillar of education is at the center of the process, which aids in both the preparation of specialized human resources and capacity building within society. Providing comprehensive care to patients and their families in PC centers requires specialized human resources in the form of an interdisciplinary team. This team, composed of various disciplines, delivers professional services with a team-based approach. Preparing these specialized teams necessitates the design and implementation of educational programs at both academic and skill levels to achieve the expected qualifications.

The emergence of PC in the health systems of EMRCs is naturally associated with insufficient training, ignorance among specialists and care providers, particularly nurses and doctors (73), and a general lack of knowledge and awareness about this type of care (4, 69). Therefore, leveraging the successful experiences of leading countries in designing curricula and appropriate graduate-level programs, and adapting these curricula to local cultures (74), as well as the pattern and burden of diseases, and holding suitable educational workshops, can help overcome these educational obstacles. Additionally, creating appropriate educational infrastructure in the fields of medicine and nursing is crucial. Conducting qualitative and quantitative studies to examine the views of different groups about PC and its training, and to assess the effectiveness of training courses, can also be beneficial (75).

Another important aspect to consider is increasing public awareness about PC. Designing and implementing programs aimed at familiarizing the general public can lead to gradual cultural acceptance and is a significant step towards establishing this type of care in society (4). Raising public awareness is one of the recommendations of the WHO (65) and has been highlighted in previous research (69). Cultural differences significantly impact the acceptance and use of these services, so it is essential to consider these differences in the design and development of PC services in any society (76). Correcting wrong beliefs, changing attitudes, and increasing awareness can only be achieved through gradual initiation and sustained efforts (72).

In terms of actors, the participation of all stakeholders is crucial in identifying the needs of the care system. Establishing a PC system depends on the involvement of groups, governmental and non-governmental institutions, and the general public. The participation of private and governmental institutions in raising awareness about the types of services and how to access them plays a significant role in formulating the care system. This finding aligns with the results of a study on the challenges of PC services in the EMR (77). Other studies also show that facilitating performance in the provision of PC depends on the consolidation of mutual and interprofessional cooperation and communication with other organizations (78).

Highlighting the range of empirical evidence available from different policy contexts is a strength of this scoping review. Our search strategy proved to be very sensitive for identifying studies of cancer PC strategies. Nevertheless, the focus on medical databases and the screening of frequency studies based solely on published summaries could limit the completeness of our review. Furthermore, because scoping studies focus on breadth of coverage rather than depth of analysis, the quality of the included studies was not systematically assessed and no syntheses of study findings were performed.

4.1. Conclusions

The results of the present study provide a clear picture of how policies are made in the field of PC design and development in EMRCs. Before establishing such a system, it is essential to consider a wide range of economic, social, cultural, and political factors, mainly included in the four axes of Walt and Gilson's policy triangle. To effectively provide palliative services, a national plan or strategy must be formulated with the support of political authorities and relevant stakeholders. This plan should include a legal framework for expedited access to painkillers, training for professionals on their prescription and use, and ensuring broad patient access to hospice palliative care, particularly in communities. Additionally, necessary financial and human resources should be allocated, along with training and the establishment of national information networks. Public awareness about these services is also crucial. Research findings can inform policy and program decisions in the PC system.