1. Background

Laryngeal cancer is the second most common respiratory tract cancer (1). It accounts for about 0.8% of all new cancer cases and 0.6% of all cancer deaths worldwide (2). The laryngeal cancer accounts for 2% to 5% of all malignancies in the body (3). The larynx has critical roles, including phonation, respiratory airflow control, and airway protection during swallowing (4). Over 95% of laryngeal malignancies are squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC). The LSCC was the second primary type of head and neck malignancy (5). The most relevant risk factors for laryngeal cancer are cigarette smoking and alcohol habits; lesser factors include gastroesophageal reflux and human papillomavirus infection (2, 3, 6). With tobacco use reduction, laryngeal cancer incidence has decreased by 2.4% each year for the last 10 years (2). There has been a decrease in the 5-year survival rate in the USA during the previous 30 years, with laryngeal cancer (7). Survival refers to the state of continuing to live, especially after dangerous situations (8). The chances of survival for patients with laryngeal cancer are strongly related to the initial stage of disease, with cure rates of up to 90% for early-stage I and II tumors and less than 40% in patients with stage IV disease at presentation (2). Unfortunately, more than 75% of patients are diagnosed in the advanced stages of the disease (stage III or IV) (9, 10).

Hoarseness is usually the first symptom of laryngeal cancer. In many cases, cancer causes vocal cord involvement and spreads to local lymphatics at diagnosis. The other symptoms of laryngeal malignancies include sore throat, cough, hemoptysis, painful swallowing, impaired voice quality, and otalgia (3). Significant predictive factors in cancer prognosis include primary tumor volume, nodal volumes, patient age, tumor behavior, grade, and depth of invasion (11). The immediate treatment of advanced laryngeal cancer is total laryngectomy (TL).

Nonetheless, transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) and partial laryngectomy have many indications for controlling early laryngeal cancer (4). A particular emphasis on regional control of all cancers with consideration of prolonged survival is an ultimate goal in cancer treatments (7). However, some clinicians strongly believe that conservation surgery approaches decrease survival rates and miss opportunities (4). Laryngeal cancer is divided into the following subtypes based on the location of tumor involvement: Supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic LSCC; supraglottic is the second most common type of laryngeal cancer following glottic area (12). The 5-year survival in treatable patients varies depending on the location of laryngeal cancer. It is 80% and 50% for glottic and supraglottic cancers, respectively (13). Despite advanced treatment procedures, patient survival and quality of life after treatment are still primary subjects in patients with laryngeal cancer (14).

2. Objectives

This study aimed at assessing the impact of epidemiological factors and clinical and demographic data on patient survival in patients with advanced-stage laryngeal cancer (stage III and IV), who underwent TL.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

This research is a retrospective observational study of 150 laryngeal cancer patients who had undergone surgery between 2015 and 2020 at Shiraz Khalili Hospital and have been followed up to now. We included the patients with advanced stages of laryngeal cancer (stage III or IV) who underwent TL and excluded those who received radiotherapy before TL.

3.2. Protocol of Study

Using the archive files, we prepared a data gathering sheet for patients, including demographic data, symptoms, risk factors, tumor characteristics, and complications after the operation. The smoker is defined by multiplying the number of packs smoked per day by the years the person has smoked (15). The history of alcohol use was divided into occasional (average of 2 or fewer drinks/day) and heavy drinkers (average of more than 2 drinks/day) (16).

3.3. Ethics Consideration

The protocol was under the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the National Committee for Ethics in Biomedical Research with the ethical code of IR.SUMS.REC.1392.5145.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The continuous variables were presented by mean ± SD, and the qualitative data were shown by frequency and percentage. The data were analyzed, using Kaplan-Meier Survey Analysis and log-rank tests. Cigarette smokers, alcohol drinkers, and advanced stages of laryngeal cancer were considered for log-rank tests. The P < 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

4.1. Patient Characteristics

Of 150 participants, 97.3% (146 cases) occurred in men (Table 1). The male-to-female ratio was 36:1, and the mean age was 62.4 years (at a peak incidence in the 6th and 7th decades). Most patients (148, 98.7%) were married, and most (72, 48.0%) had primary education. Most patients were workers and farmers (34, 51.0% and 45, 30.0%, respectively). Hoarseness was the most common symptom of laryngeal cancer patients (95.3%, 143 patients), with an average time of 354.5 ± 37.0 days, followed by dysphagia (40.7%, 61 cases, average time 259.0 ± 10.2 days).

4.2. Risk Factor Characteristics

Of all patients, 96.7% (145), (Table 1) were smokers, and 65% (98 patients) of our study population smoked > 15 pack years. In addition, 51.3% of all patients (77 cases) were opium addicts, 9.3% (14 patients) were water pipe smokers, and 12.0% (18 cases) were alcohol drinkers; 72.2% of them (13 cases) were heavy drinkers. The history of direct contact with chemicals and work hazards was negative in all studied patients. A positive family history of laryngeal cancer was 4.7% (7 cases). In addition, 6.7% of patients (10 patients) had a positive history of gastroesophageal reflux.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Patient | |

| Age (y) | 62.1 ± 11.8 |

| Gender (men) | 146 (97.3) |

| Marital status (married) | 148 (98.7) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 64 (42.7) |

| Primary | 72 (48.0) |

| High school | 13 (8.7) |

| University | 1 (0.7) |

| Occupation | |

| Worker | 51 (34.0) |

| Famer | 45 (30.0) |

| Clerk and business | 7 (4.7) |

| Military | 3 (2.0) |

| Teacher | 2 (1.3) |

| Others | 42 (28.0) |

| Symptom | |

| Hoarseness | 143 (95.3) |

| Duration (mo) | 354.4 ± 502.0 |

| Dysphagia | 61 (40.7) |

| Duration (mo) | 259.1 ± 327.0 |

| Respiratory distress | 41 (27.3) |

| Duration (mo) | 117.3 ± 112.8 |

| Throat pain | 15 (10.0) |

| Duration (mo) | 414.0 ± 647.8 |

| Neck mass | 14 (9.3) |

| Duration (mo) | 158.6 ± 102.9 |

| Cough | 13 (8.7) |

| Duration (mo) | 190.3 ± 112.6 |

| Dyspnea | 6 (4.0) |

| Duration (mo) | 204.0 ± 129.7 |

| Risk factor | |

| Cigarette smoker | 145 (96.7) |

| Opium addict | 77 (51.3) |

| Using duration (mo) | 234.9 ± 123.2 |

| Water pipe smoker | 14 (9.3) |

| Using duration (mo) | 208.0 ± 134.0 |

| Alcohol drinker | 18 (12.0) |

| Other drug abusers | |

| Heroin | 3 (2.0) |

| Crack | 1 (0.7) |

| History of gastrointestinal reflux | 10 (6.7) |

| Family history | |

| Laryngeal cancer | 7 (4.7) |

| Other cancer | 5 (5.3) |

| Chemical contact and work hazard | 0 (0.0) |

Patient and Some Risk Factors of Laryngeal Cancer in our Studied Sample a

4.3. Tumor Characteristics

Detailed information on tumor characteristics is shown in Table 2. Overall, grading in most patients was well differentiated (44.0%, 66 cases), and 58% (87 cases) were in Stage 4. The distribution of sub-sites was as follows: Glottic cancer occurred in 46% of the patients (69 cases), followed by transglottic cancer (43.3%, 65 patients) and supraglottic cancer (9.3%, 14 cases). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) was seen in 98.0% of patients. We cite the Cox regression model results in Table 3.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Tumor | |

| Grading | |

| Well-differentiated | 66 (44.0) |

| Moderate differentiated | 56 (37.3) |

| Poor differentiated | 28 (18.7) |

| Staging | |

| II | 10 (6.7) |

| III | 53 (35.5) |

| IV | 87 (58.0) |

| Site | |

| Supraglottic | 14 (9.3) |

| Glottic | 69 (46.0) |

| Transglottis | 65 (43.3) |

| Supraglottic + glottis + subglottic | 2 (1.3) |

| Pathology | |

| LSCC | 147 (98.0) |

| Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 2 (1.3) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1 (0.7) |

| Vocal cord movement | |

| Fixed | 136 (90.7) |

| Impaired | 8 (5.3) |

| Normal | 6 (4.0) |

| Treatment | |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Before surgery | 16 (10.7) |

| After surgery | 67 (44.7) |

| Radiotherapy | |

| Before surgery | 3 (2.0) |

| After surgery | 51 (34.0) |

| Surgery | |

| TL + cervical dissection | 124 (82.7) |

| Vertical partial laryngectomy + cervical dissection | 11 (7.3) |

| Supraglottic laryngectomy + cervical dissection | 8 (5.3) |

| Supracricoid + cervical dissection | 3 (2.0) |

| Sub TL + cervical dissection | 2 (1.3) |

| Trans oral laser microsurgery | 1 (0.7) |

| Anterior partial laryngectomy + cervical dissection | 1 (0.7) |

| Free margin after surgery | 142 (94.6) |

| Post-operation complication | 23 (15.3) |

| Fistula | 12 (8.0) |

| Stenosis | 7 (4.7) |

| Hematoma | 2 (1.3) |

| Infection | 2 (1.3) |

Tumor and Treatment Characteristics of Laryngeal Cancer in Our Studied Sample a

| Characteristics | Values | HR | 95% CI | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y); mean ± SD | 62.1 ± 11.8 | 1.01 | 0.99 - 1.03 | 0.256 |

| Gender (men) | 146 (97.3) | 1.21 | 0.97 - 1.4 | 0.346 |

| Cigarette smoker | 145 (96.7) | 2.21 | 0.87 - 3.25 | 0.226 |

| Alcohol drinker | 18 (12.0) | 1.65 | 1.21 - 1.86 | 0.001 |

| Grading | ||||

| Well-differentiated | 66 (44.0) | Ref | - | - |

| Moderate differentiated | 56 (37.3) | 0.98 | 0.95 - 1.04 | 0.223 |

| Poor differentiated | 28 (18.7) | 1.02 | 0.97 - 1.06 | 0.285 |

| Staging | ||||

| II | 10 (6.7) | Ref | ||

| III | 53 (35.5) | 2.23 | 1.85 - 3.25 | < 0.001 |

| IV | 87 (58.0) | 2.85 | 2.22 - 2.55 | < 0.001 |

| Site | ||||

| Supraglottic | 14 (9.3) | Ref | - | - |

| Glottic | 69 (46.0) | 1.22 | 0.89 - 1.56 | 0.562 |

| Transglottis | 65 (43.3) | 1.32 | 0.92 - 1.80 | 0.633 |

| Supraglottic + glottis + subglottic | 2 (1.3) | 1.80 | 0.88 - 2.56 | 0.227 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| Before surgery | 16 (10.7) | Ref | - | - |

| After surgery | 67 (44.7) | 2.25 | 0.95 - 2.89 | 0.321 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||

| Before surgery | 3 (2.0) | Ref | - | - |

| After surgery | 51 (34.0) | 1.89 | 0.96 - 2.3 | 0.455 |

| Free margin after surgery | 142 (94.6) | 2.32 | 0.90 - 3.2 | 0.865 |

Cox Regression Model Results (Multivariable) a

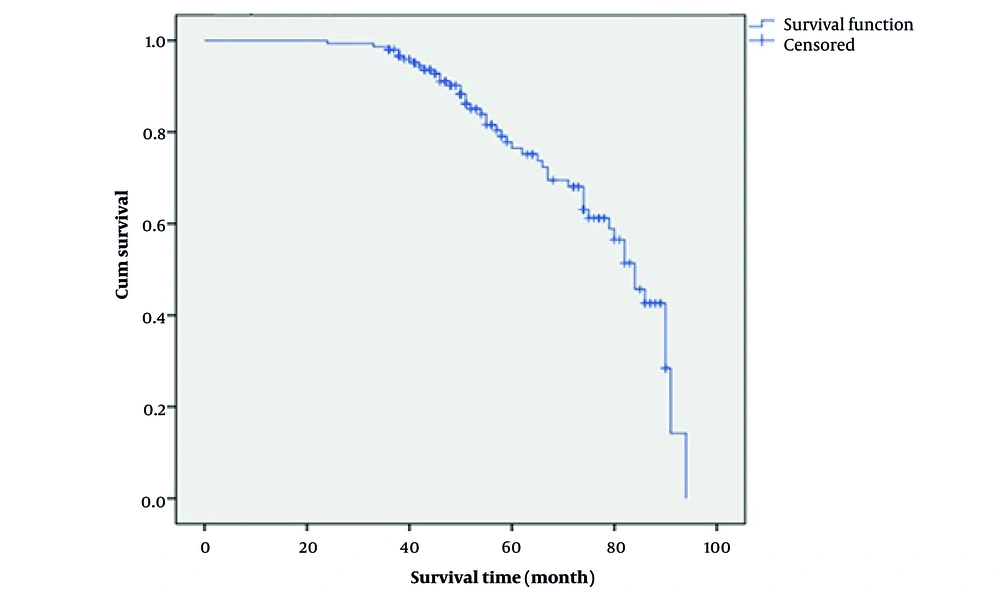

4.4. Patients' Survival Time

In general, 30.7% of our patients (46 cases) died, and 27.3% died due to cancer. The overall survival after 1, 3, and 5 years for laryngeal cancer was 99.3%, 97.0 %, and 76.5%, respectively (Figure 1).

Survival median was 87, and overall survival with a 95% confidence interval was from 78 to 96. Also, disease-specific survival (DSS) after 1, 3, and 5 years for laryngeal cancer was 14.8%, 17.9%, and 26.4%, respectively.

However, margin involvement in patients with laryngeal cancer worsens the prognosis and reduces survival. Since our patients underwent TL, and we had only 8 microscopic-involved margin patients, we could not evaluate the survival based on margin involvement.

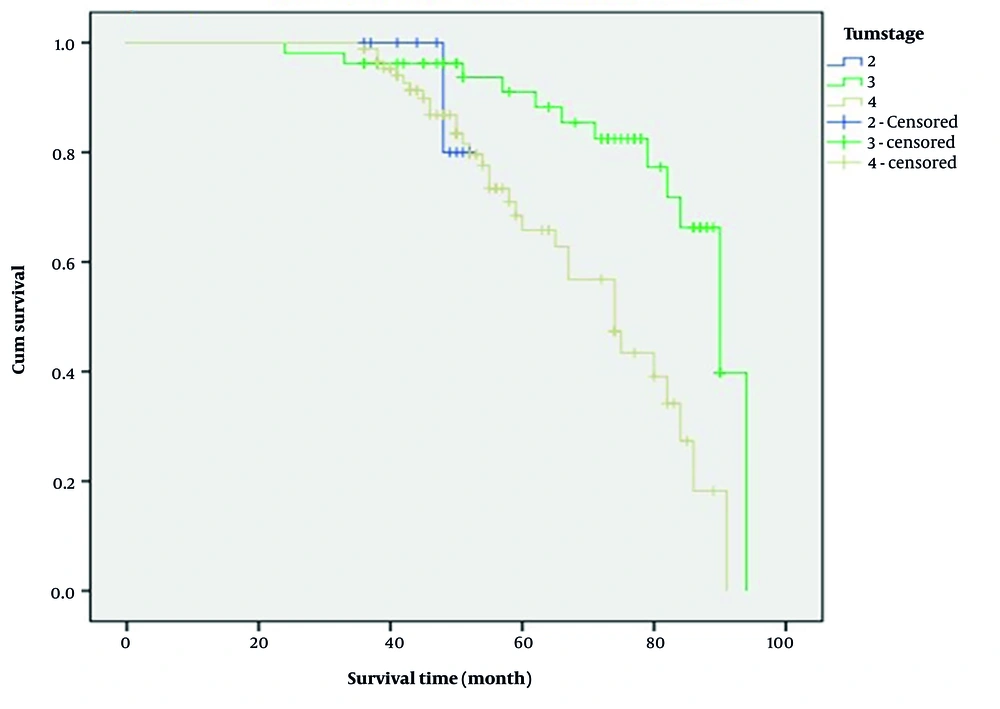

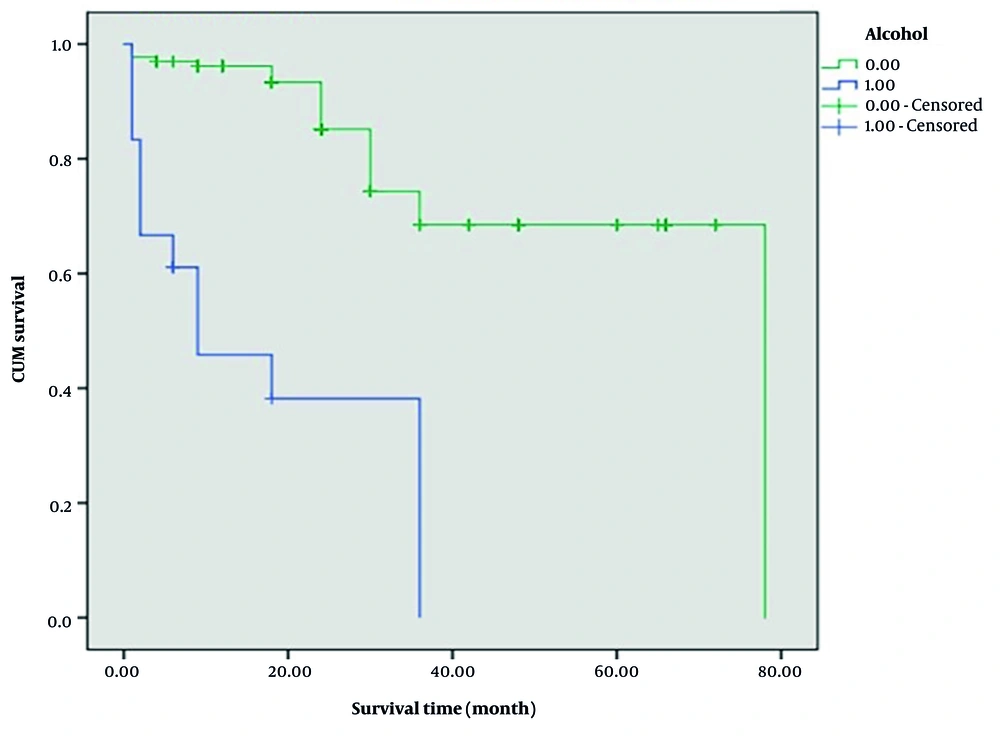

Moreover, patients with stage 3 significantly had a higher 5-year survival time than those with stage 4 (91.0% vs. 68.4%; log-rank: 12.6, P = 0.002, Figure 2). Kaplan-Meier survival curve showed that 1-year survival was worse among patients who had a positive history of alcohol consumption (45.8% vs. 96.2%; log-rank: 13.8, P < 0.001, Figure 3).

Since smoking is the leading risk factor for laryngeal cancer, and we had only 5 non-smoker patients (1 died), we could not evaluate the survival based on smoking. Patients with well and moderate tumor differentiation had a nonsignificantly better survival than patients with poor tumor differentiation (78.6% and 77.2% vs. 75.2%, respectively; log-rank: 2.8, P = 0.240). When analyzed for tumor site, glottic tumors had a better prognosis; however, no significant differences were found (P = 0.208). Also, there were no significant differences based on vocal cord movement; normal vocal cord movement had better survival (log-rank: 102.0, P = 0.950). There was no significant change in survival time related to other risk factors (P > 0.005).

5. Discussion

Our study is the first to evaluate the survival in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer and to assess the effect of staging on survival. The findings of this study revealed that alcohol consumption negatively impacts the survival of patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. Although the effect of smoking on survival was not statistically significant due to the small number of non-smoking patients (5 cases), clinically, a higher percentage of advanced laryngeal cancer patients were smokers.

In terms of tumor characteristics, the high tumor stage had a negative impact on survival, but tumor differentiation and location had no significant effect on survival.

In some studies, the effect of alcohol consumption on the development, progression, and metastasis of colorectal, breast, stomach, oral cavity, pharynx, and lung cancer has been shown (17, 18). Zhao et al. showed that alcohol consumption leads to increased expression of C-C chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5) and induction of autophagy that causes tumor progression and metastasis in colorectal cancer (19). Saad et al. found that alcohol consumption may induce dysregulation of miR-30a and miR-934 in head and neck cancer development and progression (20). Pan et al. also found that alcohol consumption is related to worse survival in laryngeal cancer (21).

Although smoking is known as a risk factor for laryngeal cancer, its effect on the survival of these patients is not well recognized, and there is some controversy about it. Some investigations have shown that smoking can dysregulate miRNA expressions, like the miR-202-3p and miR-29c-3p, which determine tumor progression and metastasis in laryngeal cancer (22, 23). On the other hand, Giraldi et al. showed that smoking does not affect the survival of patients with head and neck cancer (24). Our study showed that although it was not statistically meaningful, many smoking patients had lower survival rates than non-smokers. We believe that the reason for the lack of significance in the statistical analysis was the high number of smokers (145) compared to non-smokers (5) in the study, which impacted statistical results.

Regarding tumor stage and survival, the findings of our study are similar to those of other published studies. Many studies have revealed that the advanced stage (T3, T4) is associated with poor outcomes, low survival, and a higher probability of tumor recurrence (25-27). Studies have shown that the worsening of survival in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer is predominantly due to the positive node status. In addition to determining survival in the primary tumor, node positivity also occurs after treatment and plays a major role in the poor outcome of laryngeal cancer (26, 27).

Tumor cellular differentiation and its effect on survival are a controversial issue. In the study conducted by Starska et al., no significant correlation between tumor differentiation and survival was found (28). The result of this study was consistent with our research that there was no significant relationship between well-differentiated, moderate, and poorly differentiated laryngeal tumors with survival. On the other hand, studies have shown that poorly differentiated tumors have a lower survival rate than moderate and well-differentiated laryngeal cancers (29, 30).

There are also different opinions about the role of the subsites in the survival of laryngeal cancer patients. In our study, glottic and transglottic subsites were the most, followed by supraglottic and a minimal number of subglottic with supraglottic and glottic tumors. No significant relationship between tumor subsites and survival was found in our patients. Allegra et al. also found similar results on the role of subsite variables on survival (6). Other studies have shown a negative impact on survival in supraglottic tumors. Delayed diagnosis and higher nodal involvement cause increased recurrence and decreased survival in patients with supraglottic cancer (26, 31). The different results in a few studies, such as ours, can be due to the various occurrences of supraglottic tumors in investigations.

Our study is a retrospective research, which is one of its limitations. Although the number of patients is sufficient compared to similar studies, there is a need for prospective studies with larger sample sizes to reach statistically significant results, especially regarding clinically significant findings. In this study, the effect of known risk factors on survival has been investigated, and therefore, controversial risk factors such as HPV infection on laryngeal cancer have not been evaluated. In this study, the patients included were homogeneous in terms of disease stage and treatment methods to reduce the confounding factors.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study revealed that alcohol consumption had a negative impact on the survival of patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. Although smoking was not statistically related to survival due to the small number of non-smoking patients, a remarkable number of smokers had worse survival than non-smokers. In terms of tumor characteristics, the tumor stage had the most significant effect in reducing survival. Tumor differentiation and subsite did not correlate with survival in this study. Further prospective studies with a larger sample size are needed to determine the factors influencing the survival of patients with advanced laryngeal cancer.