1. Background

Cancer is the leading cause of death among children aged 1 - 14 years Iran (1). Iran, with a population of 84 million, has a population growth rate of 1.18% and approximately 24% of its population is under the age of 14 (2). According to the Global Cancer Observatory statistics, out of every 1,567 children diagnosed with cancer, 1,037 cases die, which reflects the need for pediatric palliative care (PPC) services (3). Although the survival rate of children in developed countries has increased to 80%, in developing countries it is only about 15% - 45% (4), the underlying reasons include factors such as late diagnosis, the lack of access to services, withdrawal from treatment, and increasing the rate of relapse (3). In such situations, PPC is necessity (5).

Based on global ranking of PPC, Iran is categorized at level 3a, meaning that services are provided sporadically, this represents an improvement compared to 2014 (6, 7). However, a small number of children have access to these services (8). The current state of these services has shown that there are several challenges remain. A significant barrier is the lack of training among healthcare providers (9). Also, a lack of specialties, financial issue and limited resources are common challenges for delivery these services well (10-12).

In Iran, due to the lack of these services, the quality of life in children and their parents has been reported to be low. Increasing the burden of care, role interference, unmet needs, and family dysfunction are some of the challenges experienced in the family of a child with cancer, which increases the need to launch these services in Iran (13-16). Another study considered end-of-life care among children as one of the care challenges for the family, which shows the different aspects of the need for palliative care (8, 11, 17). While the world is moving toward community-based services, equitable access to palliative care services is recognized a fundamental human right (18).

As the World Health Organization (WHO) suggested in 2014, PPC should be integrated as a key component into the health system of every country (19). Palliative care is still in the early stages of development in most countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Regional (EMRO). Pediatric palliative care is a key indicator of the development of palliative care services in the EMRO region. However, official data had indicated that the EMR has low access to pediatric palliative care services, with an estimated 5% of people in need of palliative care in the region having access to services (11, 17, 20, 21). So, access to palliative care for children is a “moral responsibility of health systems”.

In order to achieve this goal, Iran, in cooperation with Ministry of Health (MOH), chose Mofid Children Hospital as a pilot center to run PPC. Regardless of the fact that the provision of these services in every country depends on the social and economic conditions of that country and has its own challenges, providing operational experience of PPC in different countries, including Iran, can be used as an operational model in the countries with similar conditions. Therefore, this study was conducted to present the experiences and the measures taken so far in the field of establishing and providing PPC in Iran.

1.1. Pilot Project of Establishing an Outpatient Clinic of Pediatric Palliative Care in Mofid Hospital

Mofid Children's Hospital is one of the specialty children’s centers in Tehran with 311 beds in 17 wards. The Department of Pediatric Oncology has 36 beds in three wards: Oncology, transplantation and chemotherapy, and annually admits about 500 children with cancer from all over the country (11).

As a comprehensive center for children, this center has always provided all support services such as psychotherapy, nutrition, physiotherapy, physical medicine as well as specialized medical consultation to children with cancer, and is a suitable place to develop and provide supportive and palliative care services in a systematic manner. Therefore, considering this understood need in the country and the readiness of the center's president to provide palliative care services, this center was selected as pilot center. According to this plan, an agreement was signed between them. The project was also funded by the Nursing Deputy of the MOH, No. 139/423on jun 23.2021.

2. Objectives

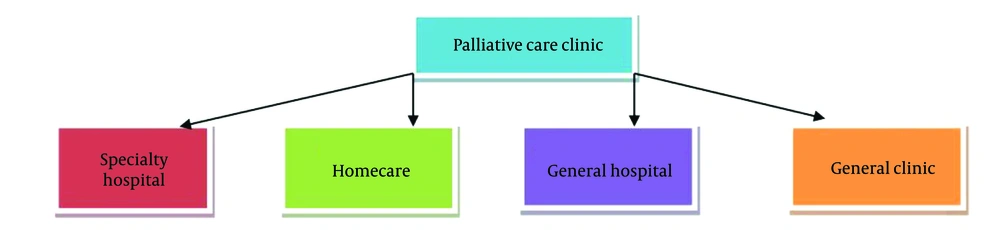

In order to implement this plan, several studies such as a PhD thesis with the title "Designing pediatric palliative care model in Iran", were conducted. In this proposed model, which was designed based on HUB-spoc model, the outpatient clinic in Mofid Children's Hospital was selected as the hub and main center, which has a link between the hub and other community centers (18) (Figure 1).

3. Methods and Results

The establishment of a PPC clinic at Mofid Children's Hospital in 2021 was carried out according to the WHO guidelines, following these 11 steps (19).

3.1. Conduct Needs Assessment

This step was conducted to determine the needs of palliative care for children with cancer in Iran through two sub-studies: A review study and a qualitative content analysis study. In the review phase, searches were conducted using MeSH keywords such as "cancer", "children", "family", "palliative care", "hospice", "end of life", and "needs" in national databases (SID, Magiran, Iran Medex) and international databases (Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, ProQuest, Medline Plus, EMBASE, Cochrane Library). These searches period was between 2014 and 2024.

In the initial review phase, 55 papers were identified. After removing duplicates, applying screening criteria based on title and abstract, assessing accessibility to the full text and selecting studies that focused on children and their families' needs, 32 papers remained. Then full-text evaluations resulted in the exclusion of 13 papers. Finally, data from 19 papers were utilized.

In the second phase, to incorporate of stakeholder perspectives — including caregivers, children, families, policymakers, and professionals — the results of the previously conducted content analysis were used. Most experts believed that clinics in specialized hospitals were the best model for the country. A detailed explanation of this process is available in previously published articles (8, 22-26).

The information obtained from the literature review phase was analyzed alongside data extracted from qualitative interviews using directed content analysis. It was organized into steps for establishing a palliative care clinic in the hospital, classified according to WHO guidelines. The results of this phase indicated that the needs of children and families in various dimensions — physical, psychological, social, and spiritual — were still unmet.

3.2. Define Priorities and Target Population

Mofid Children’s Hospital was selected as the center for pediatric palliative care services. Based on the studies conducted and the implementation of the Global Action Plan in Iran, children with cancer were identified as the target population.

3.3. Seek Support of Hospital Management and Senior Clinicians

In line with the realization of this step, the hospital administrators raised the issue of "problems faced by cancer patients in the hospital," highlighting consequences such as the high occupancy rate of emergency beds by these patients and the delay in their treatment due to the shortage of hospital beds. Discussions, exchanges of views, and the presentation of various solutions led to the agreement of the hospital's president and director to provide palliative care services. To this end, a task force was formed, consisting of nurses, pediatric specialists, and pediatric oncology specialists, who held regular meetings to plan the launch of this service. The activities of this committee, whose members currently include the hospital president, director, treatment deputy, educational deputy, nursing director, head of the oncology department, focal point for oncology, and focal point for nursing, continue to this day. They are responsible for managing and overseeing the project.

3.4. Identify Focal Person to Lead the Initiative Within the Hospital

At this stage, to facilitate the planning and implementation of the program, a pediatric oncology specialist (PE) and a nurse (LKH) were selected by the hospital president and introduced to the Nursing Deputy of the Ministry of Health.

3.5. Sensitize Hospital Staff Members to the Philosophy of, and Need for, Palliative Care

Stakeholder sensitization in the hospital was carried out through a one-day seminar on pediatric palliative care, aimed at familiarizing them with these services. To further raise awareness, this concept (the services) was presented during morning reports and staff meetings by the medical focal point. Additionally, for the nurses, periodic educational workshops on palliative care were held at the hospital, with the goal of familiarizing them with the concept and philosophy behind providing this care.

3.6. Make Efforts to Promote Palliative Care via a Public Awareness Campaign

Since this concept was very new in the country and not well known to care providers and experts, most activities were focused on raising awareness within the healthcare team.

3.7. Identify the Gaps in the Hospital Infrastructure

Provision and enhancement of infrastructure were planned around three main areas: Physical space, human resources, and their empowerment.

The physical space, according to the Ministry of Health (MOH) guidelines for the establishment of palliative care, is approximately 100 square meters with 2 rooms with 2 beds, a consultation room, a treatment room, and a nursing station adjacent to the hospital's emergency department. There are also full facilities for hospital care, as well as child and family welfare facilities. This clinic is one of the hospital departments in connection with other departments, including oncology, intensive care, surgery, internal medicine, and other departments.

Human resources, despite the challenge of a shortage of personnel, include one full-time nurse and two part-time nurses, a pediatric oncology specialist, a nutrition specialist, a psychiatrist, a full-time social worker, a part-time pain specialist, as well as volunteers. If additional specialties are needed, they are present in the team in a consulting capacity. The payment for personnel is made through a contract with the Maksa charity center, which works in the development of palliative care centers for cancer patients.

Empowering human resources, based on the needs assessment conducted in the first phase, was planned in the form of two fundamental and advanced courses. The training in the introductory course was organized through structured sessions over 12 weeks, covering 8 topics related to the introduction of childhood cancer in Iran, as well as analyzing the hospital situation and introducing the project, the philosophy and principles of palliative care, communication with the child and family, teamwork in palliative care, collaborative decision-making, the psychological and social aspects of cancer in children and families, and delivering bad news to the child and family. Initially, the training focused on the care team, including doctors and nurses in oncology, emergency, and ICU departments, who had the most interactions with these patients. The advanced course was also planned based on symptom management. Additionally, informal training was conducted in the form of journal clubs and on social platforms such as WhatsApp.

3.8. Establish a Budget for the Set-up and Recurrent Costs and Identify Funding Sources

As this clinic was created within a government hospital, all funding comes from the government (the University of Medical Sciences). Moreover, the Ministry of Health (MOH) set aside a budget to support the initiation of this project. The contribution of charitable organizations in aiding this project has also been significant. Build links with health professionals in the hospital and the community to encourage referrals.

3.9. Establish Protocols for Referral and Registration of Patients

In this clinic, the service provision process is available 24 hours a day, in-person and via phone (8 AM to 4 PM). Patients can visit the clinic through three avenues: The hospital, the oncology clinic, or as outpatients. If a patient visits the hospital, they will first go through a triage process; if they are categorized as level 3 or 4, they will be referred to the clinic. However, if they are at level 1 or 2, they will be admitted to the emergency department and then to the necessary ward, such as the ICU.

In the clinic, an initial consultation is performed by a doctor and a nurse. If symptoms are mild, patients will be treated as outpatients with a consultative approach. In cases of moderate to severe symptoms, they will be admitted to the clinic for palliative care. Upon discharge, patients are provided with the clinic's phone number for follow-up consultations.

The phone service is available to answer family questions, offer consultations, and refer patients to the nearest healthcare center if needed. This telephone consultation is only active from 8 AM to 4 PM because this is when trained doctors and nurses are present in the clinic.

The delivery of services at this clinic relies on Figure1, HUB-Spoc model, currently the focus is on the hub itself. It is important to mention that the feasibility of connecting services provided in the hospital to home care services is being investigated.

3.10. Ensure that Patients Accept the Care Model and Setting

While there is currently no documentation showing that patients have embraced this care model, site visits and verbal interviews with patients suggest their contentment. A frequently heard quote among them was "We no longer waste time in the hospital, and our children are managed and cared for with better quality." Additionally, satisfaction with the physical structure, which fulfills the requirements of families, has also been frequently noted. It is worth noting that measuring satisfaction is an ongoing process as part of the overall evaluation.

3.11. Monitor and Evaluate the Palliative Care Service to See Whether Objectives Are Being Met

This clinic has been operational since 2021. Concurrently with the implementation of the project, a cost-effectiveness plan for the services provided at the clinic was approved by Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and is currently being implemented. In this study, in addition to estimating direct and indirect costs, satisfaction is assessed as a crucial factor in evaluating the outcomes of palliative care.

4. Discussion

The presented report is part of the experience of the palliative care team in establishing an outpatient pediatric palliative care clinic at Mofid children,s Hospital in Tehran. The challenges encountered and the solutions found to overcome them were among the key lessons learned during this project. The most significant challenges experienced in this project were in the areas of stakeholder sensitization, human resources, training, and monitoring services to achieve goals.

Stakeholder sensitization was an important step in launching this project, which was achieved by increasing the medical team's knowledge about PPC. Lack of awareness is one of the major barriers to accessing palliative care services (27). In Iran, there is a lack of sufficient knowledge among the public and the healthcare team regarding palliative care (28-30). Various methods have been identified to increase awareness of palliative care, such as campaigns, brochures, booklets, media, celebrity involvement, seminars, and others. To address this issue, holding seminars and presenting this concept at various meetings has proven to be highly beneficial for this project. Along with this, Doherty and Thabet demonstrated that by raising public awareness as well as educating the healthcare team, they can facilitate the establishment of these services (31). In addition, culture was also a very influential factor, as Iranians are very sensitive to cancer, they usually try to help for decreasing of burden of this disease for patients and their families (18).

The provision of human resources was another significant challenge for this project. One of the challenges facing Iran's healthcare system is the shortage of nursing personnel and a lack of interest in working in oncology departments. Due to a high workload, limited specialization in oncology nursing, and economic constraints, many nurses are reluctant to work in these departments (32). In these conditions, training specialized oncology nurses, like in other countries, would be a solution to overcome this problem (33). Social workers and psychologists are also key members of the palliative care team, but in this project, there was a shortage of them. In this hospital, only two social workers were working, which is very limited, and it is expected that they would not be able to cover the patients' needs adequately in this clinic. To overcome this issue, the principle of hospital signed a contract with Maksa Charity and they hired a social worker and psychologist for clinic. In this clinic, there are one full-time and 2 part time nurse, a social worker, a psychologist, a physician and a pediatric oncologist. They provide services 24/7.

One of the identified gap in hospital infrastructure was the empowerment of health care providers, and implementing organized training programs was the most crucial steps for overcoming that. Training can be implemented both formally and informally (34). In Iran, there is one center that provides a restricted fellowship in palliative care as a specialist, and the participants count is low because of the limited attractiveness of the job market. The only formal courses available in Iran are short-term palliative care training programs offered by the MOH (35). Other training activities are mostly conducted by the universities, cancer research centers and etc. Additionally, training 23 nurses and doctors in a six-month fellowship program by the WHO, in collaboration with the MOH, is another achievement. Even with all these efforts, there is still a lack of knowledge and an appropriate attitude regarding palliative care among the healthcare providers in the country (35, 36). Although this project, which included organized palliative care courses, workshops, and classes, greatly enhanced the team's knowledge, it seems that incorporating this concept into medical and nursing curricula is the only viable solution. In this regard, a study conducted in the EMRO Region also identified the lack of education as a common need among all countries in the area (34). Also, it is important to note that most countries ranked at the same level as Iran in PPC (i.e., 3A) have identified the necessity for education as a major obstacle (37).

Base on the last phase of the WHO model, an additional challenge was the absence of evaluating tools for monitoring. In this project, because the palliative model is new, no specific framework was created for this step. To overcome this problem, in collaboration with the Pediatric Congenital Hematologic Disorders Research Center (PCHDRC), a project titled "Evaluation of the Cost-Effectiveness of Services in This Care Model" has been approved and is currently ongoing. This project has done in order to convince policymakers regarding the developing of these services in the country. Although this project is an important step in addressing this challenge, further support from research centers is needed (35).

In addition to the mentioned solutions for overcoming challenges, collaboration with other organizations and individuals would be beneficial in addressing further challenges.

4.1. Conclusions

The first pediatric palliative care center, established as a hospital-based outpatient clinic, was launched at Mofid Children’s Hospital in accordance with WHO guidelines after completing 11 steps. By identifying and analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of this project, the next phase will focus on expanding these services to the community level, particularly through home care centers.

4.2. Limitations

A limitation of this study was the lack of comprehensive data on the needs of children with cancer and their families. Further research is recommended to identify these needs and assess the current state of palliative care in Iran. Additionally, as this was a new project, some steps, including patient acceptance of the model, could not be fully implemented. Conducting further research in this area would support the nationwide expansion of these services.

Moreover, evaluating the effectiveness of this model could inform its adaptation for providing palliative care services to children with other chronic diseases. It is also recommended to develop strategies for training volunteers and establishing infrastructure for telemedicine services to improve accessibility to resources.