1. Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) has the biggest size among the Herpes family with the cellular size of 150 - 200 nanometer (1). This virus cannot be morphologically differentiated with the other Herpes viruses (2). CMV is widely distributed worldwide and can infect all age groups (3). Different organs can be involved by this infection such as eye, gastrointestinal system, liver and blood cells. It also causes latent infection which is systemically transmitted through the blood (4). HCMV infection is one of the most important factors of mortality among immunocompromised individuals such as transplant receivers, HIV infected /AIDS patients and newborns (5, 6). In human, CMV is transmitted by direct contact with contaminated secretions and is usually asymptomatic. But it can remain latent within kidney, lung, gastrointestinal tract and uro-genital system. Patients with T cell immunodeficiency particularly fetus, preterm neonates, transplant receivers as well as HIV infected patients are at a higher risk of CMV infection. This virus is the most common factor for congenital and prenatal infections (5-10).

Maternal infection, especially during the first trimester of pregnancy, increases the probability of acute fetal infection and neural, ophthalmic and hearing disabilities leading to high amount of costs and problems (11). Moreover, primary retrograde maternal infection can cause fetal infection. Fetal transmission rate during maternal primary infection is 40% - 50%, while this rate is only one percent during the retrograde infection. In addition, symptoms and complications following the primary infection are much more than those in secondary infection. About 5%-15% of the CMV infected neonates, due to primary maternal infection, have symptoms such as growth retardation, hepatosplenomegally, thrombocytopenia, pneumonia, microcephaly, brain calcification and hearing loss at birth. Approximately 10-15% of them develop hearing loss, visual loss and growth problems during the next years. Seroprevalence of CMV infection is directly associated with cultural and socioeconomic status of population (12).

Infectious factors during pregnancy are of great importance, because they not only threaten maternal life, but also lead to fetal mortality and congenital malformations. Maternal involvement especially during the first trimester can cause acute fetal infection and neural, ophthalmic and hearing disabilities with a lot of cost and other problems (11). CMV infection is one of the most important congenital infections, so that 10-14% of infected fetuses develop abnormal clinical signs and symptoms especially neural complications and hearing loss. The main determinantal factor for congenital outcomes in neonates is the type of maternal involvement (primary or secondary) (13). Of congenitally infected neonates, 90% are symptomless at birth, while 5-17% show some clinical manifestations. Among symptomatic newborns, 20% will die and 80% experience severe complications (14, 15). Neonatal mortality rate is approximately 30% and 80% of live neonates have severe neurological outcomes (11).

CMV seroprevalence is related to different epidemiological factors (8). This prevalence varies between 40% to 100% in different parts of the world (7). Arabpour et al. (2007), in a study conducted among women during fertility age in Fars province, showed that IGM sero-prevalence rate is directly associated with age, while inversely associated with high abortion. In addition, prevalence of infection is more common among rural women compared to urban ones. They also showed primary HCMV infection in 2.4% of pregnancies and estimated that up to 0.3% of congenital abnormalities were due to HCMV infection. This study indicated that neonate and menarche have a major role in HCMV prevalence among fertile women (16). Another study carried out by Smithers-Sheedy et al. (2015) in Australia reported that 83% of CMV associated mortalities have occurred among children under 15 (17).

According to the electronic searches, various studies have been carried out regarding the IGM and IgG seroprevalence and primary infection prevalence of CMV among women and neonates reported a wide range of prevalences. To determine a reliable estimate of CMV infection prevalence, combining the results of such primary studies could be a reasonable strategy. The current study aims to estimate the pooled prevalence of CMV infection among different subgroups using meta-analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

The current study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of determining the CMV IgM/IgG seroprevalence as well as primary infection of CMV in Iran which was conducted based on the review of literature.

2.1. Search Strategy

To identify the electronically published articles from 1990 until 31 March 2015, National (SID, Iranmedex, Magiran, Irandoc) and international (PubMed, Google scholar, Scopus and Science direct) databases were used. The search strategy was performed by means of the following keywords or their persian equivalents:

“Prevalence”, “Seroprevalence”, “Ferequency”, “Seroepidemiology”, “Cytomegalovirus”, “Maternal Infection ”, “Primary Infection ”, “Secondary Infection ”, “HCMV ”, “CMV-IgG ”, “CMV-IgM ”, “Congenital Disorders” “Pregnant Women”, “Iran”

This search was conducted between 1-10 April, 2015. Moreover, to increase the search sensitivity, we investigated the references listed at the end of the articles. One of the researchers randomly evaluated the search process and found no omitting of any relevant paper.

2.2. Study Selection

We extracted full texts or abstracts of the papers and other evidences found by advanced search. After exclusion of the duplicated articles, irrelevant papers were removed by reviewing the titles, abstracts and full texts respectively. To reduce the risk of publication bias, we interviewed some experts and staff of the research centers to provide probable un-published papers. Finally, another researcher randomly evaluated this search and found that all relevant studies had been collected in the search. In addition, we estimated eagle and begg indicators to evaluate the degree of bias. In order to prevent the re-publication bias, we investigated the results to identify and exclude the repeated studies.

2.3. Quality Assessment

After identifying the relevant papers regarding the titles and contents, their quality was assessed using a previously applied checklist (18). This checklist (18) was designed according to the STROBE checklist (19) contents including 12 questions assessing different aspects of methodology such as sample size estimation, type of the study, sampling methodology, study population, data collection method, variable definition, data collection tools, statistical tests, aims of the study and illustration of the findings according to the objectives of the study. Each question was assigned a score and studies that achieved at least eight quality scores were eligible to enter in the final meta-analysis. This checklist was designed to avoid any individual bias influences on the quality score.

2.4. Data Extraction

All required data such as title, first author name, study date, sample size, IgM/IgG seroprevalence as well as primary and secondary infection prevalence of CMV (all women, pregnant women and neonates), CMV recurrence rate, type of the study, sampling methods, place of the study conduction, study language and mean age of pregnant women were extracted by two independent researchers. We then assessed the level of agreement between the results obtained by these two researchers. These data were inserted in the Excel spreadsheet.

2.5. Inclusion Criteria

All Persian and English-written papers passing the above evaluation phases and obtaining the required quality scores and estimating the CMV infection seroprevalence or primary/secondary infection rate among different population subgroups in Iran were selected for meta-analysis.

2.6. Exclusion Criteria

Studies did not report the CMV infection prevalence, studies with unknown sample size, abstracts presented in congresses without full text and case-control or experimental studies without certain estimate of prevalence and finally studies without required quality score (less than 8) were excluded from the final systematic review and meta-analysis process.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using Stata SE. V.11 software. Standard error of the infection prevalence was calculated based on the binomial distribution equation. Heterogeneity between the results of the studies was detected using Cochrane (Q) test and I square index. We used fixed effect or random effects model to estimate the pooled prevalence of CMV infection in Iran. In addition, to minimize the random variations among point prevalences, all results were adjusted using Bayesian analysis technique. Moreover, sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify the studies influencing the heterogeneity. Forest plots were designed to illustrate point and pooled prevalences and 95% confidence interval of CMV infection. In these plots, size of each box indicated the study weight, while the crossing lines showed the 95% confidence intervals.

3. Results

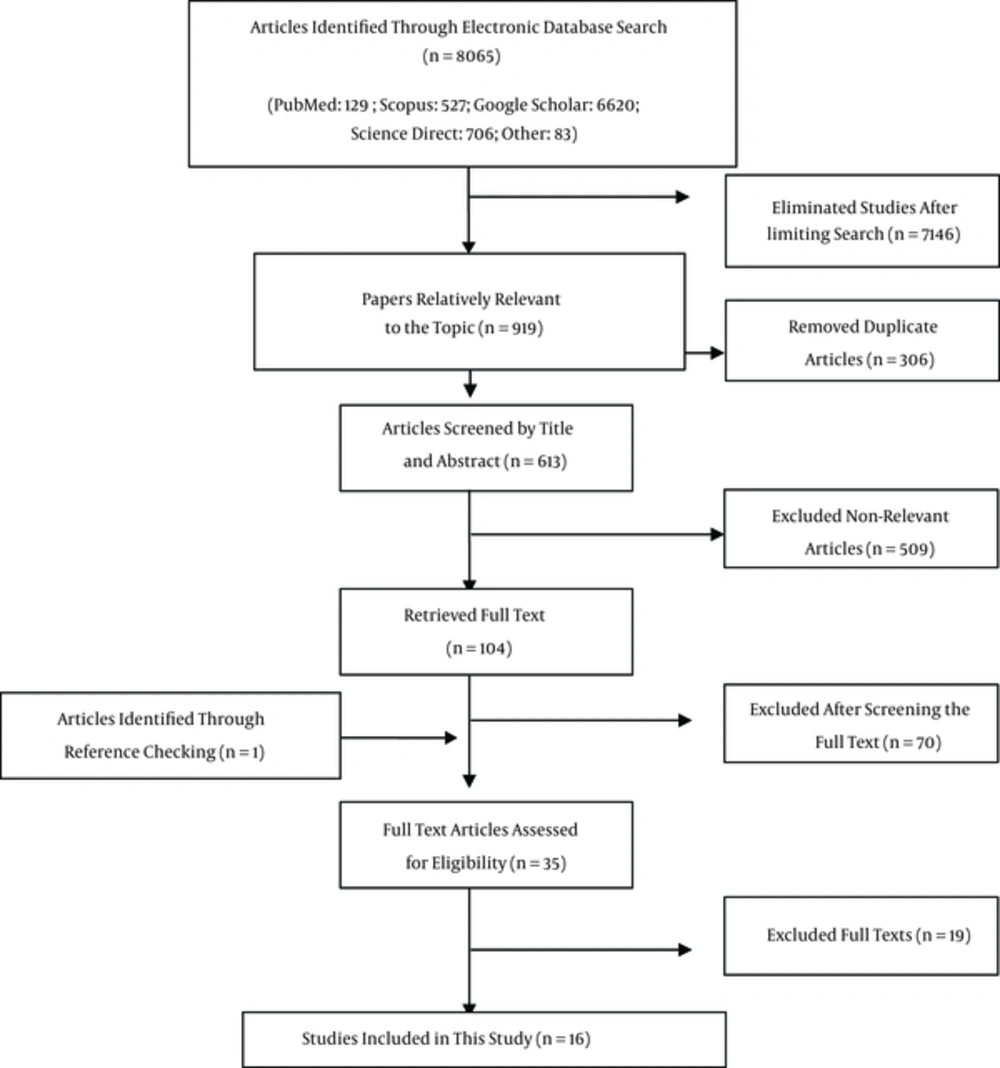

We identified 8065 articles during our systematic search, decreased to 919 papers after limiting the search strategy. Having excluded duplicated articles, 613 papers remained. After investigating the titles and abstracts, 509 papers were omitted. Review of the full texts removed 70 studies from the process. One article was added to the list after reviewing the references. The resting evidences were assessed regarding the inclusion/ exclusion criteria as well as quality assessment checklist leading to exclusion of 19 articles. Finally, 16 studies entered the meta-analysis process (Figure 1, Table 1). It should be noted that in four studies, prevalence of infection was reported in both pregnant women and their neonates.

| First author | Publication Year | Group Population | Language Publication | Sample Size | Seroprevalence of (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-CMV IgG | Anti-CMV Igm | Primary infection | Secondary infection | recurrent infection | |||||

| Erfanianahmadpoor (20) | 2014 | Pregnant | EN | 225 | 100 | 2.6 | - | - | - |

| Arabzadeh (11) | 2007 | Pregnant | Persian | 397 | 91.9 | 33.8 | 0.7 | 32.2 | - |

| Janan (21) | 2013 | Pregnant | Persian | 360 | 77.3 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 21.1 |

| Rajaii (4) | 2009 | Pregnant | EN | 125 | 76 | 8 | 6.4 | - | - |

| Siadati (22) | 2002 | Pregnant | EN | 164 | 100 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Monavari (13) | 2012 | Pregnant | EN | 100 | 100 | 3 | - | - | - |

| Bagheri (23) | 2012 | Pregnant | EN | 240 | 69.6 | 2.5 | 0.8 | - | 1.7 |

| Tabatabaee (24) | 2009 | Pregnant | EN | 1472 | 97.7 | 4.3 | 1.5 | - | 2.8 |

| Fallahi (25) | 2009 | Abortion | Persian | 42 | 14.3 | 28.6 | - | - | - |

| Janan (8) | 2014 | Abortion | Persian | 40 | 100 | 17.5 | 17.5 | - | - |

| Zandieh (26) | 2005 | childbearing age | Persian | 100 | 95 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Golalipour (27) | 2008 | childbearing age | Persian | 64 | 69.8 | 4.7 | - | - | - |

| Erfanianahmadpoor (20) | 2014 | Infants | EN | 225 | 100 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Monavari (13) | 2012 | Infants | EN | 100 | 99 | 2 | - | - | - |

| Siadati (22) | 2002 | Infants | EN | 16 | 0 | - | - | - | |

| Arabzadeh (11) | 2007 | Infants | Persian | 397 | 0.7 | 0.7 | - | - | |

| Arabpour (16) | 2007 | childbearing age | Persian | 844 | 93 | 5.4 | 2.4 | - | - |

| Delfan-Beiranvand (3) | 2012 | Blood Donors | EN | 26 | 50 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Mehrkhani (28) | 2011 | Immunodeficiency | EN | 29 | 93 | 0 | - | - | - |

| Sharifimod (29) | 2001 | Blood Donors | Persian | 123 | 89.5 | 6.3 | - | - | - |

Publication dates of the studies varied between 2001 and 2014. Eight articles were written in English. Diagnostic test was ELISA in 12 studies, while four studies did not report the name of laboratory exam. Type of study was cross sectional or descriptive in 12 studies.

In eight studies estimating the CMV infection prevalence among pregnant women, mean age was reported between 22.4 years (22) and 28.7 years (21). IgG seroprevalence among pregnant women varied between 69.6% in Bagheri study (23) with sample size of 240 and 100% in the study carried out by Erfanianahmadpoor (20), Siadati (22) and Monavari (13). Having adjusted the results using Bayesian analysis, the seroprevalences were estimated between 82.2% and 99.9%. IgM seroprevalence of CMV infection among pregnant women was reported from zero (22) to 33.8% (11) restricted to 0.2% and 28.6% respectively after Bayesian adjustment. Prevalence of primary infection among pregnant women was reported in five studies varied between 0.7% (11) and 6.4% (4). Only two studies (11, 21) reported the prevalence of secondary infection among pregnant women (32.2% in Arabzadeh study (11) and 0.6% in Janan study (21)).

IgG seroprevalence of CMV infection among neonates was reported only in two studies as 100% in Erfanian Ahmadpoor (20) & Siadati study (22) and 99% in Monavari study (13). No meta-analysis was conducted because of the low number of the studies. IgM seroprevalence was reported in four studies varied between zero (Erfan Ahmadpoor (20) & Siadati (22)) and 2% (Monavari (13)). Moreover, only Arabzadeh (11) reported the prevalence of primary infection which was 0.7% in neonates.

Among the selected articles, eight studies reported the CMV infection prevalence in groups other than pregnant women and neonates, two of which were women with history of abortion. IgG and IgM seroprevalences of CMV were 14.3% and 28.6% respectively in Fallahi study (25). The corresponding figures were 100% and 17.5% in Janan study (8). Of the three studies estimated the seroprevalence among women in fertility period, IgG seroprevalences were reported from 69.8% (27) to 95% (26) and IgM prevalence rates were reported from 1% (26) to 5.4% (16). Only two studies reported the IgG and IgM CMV seroprevalence among blood donor women varied from 50% and zero respectively (3) to 89.5% and 6.3% respectively in the study carried out by Sharifi Mood (29) (Table 1).

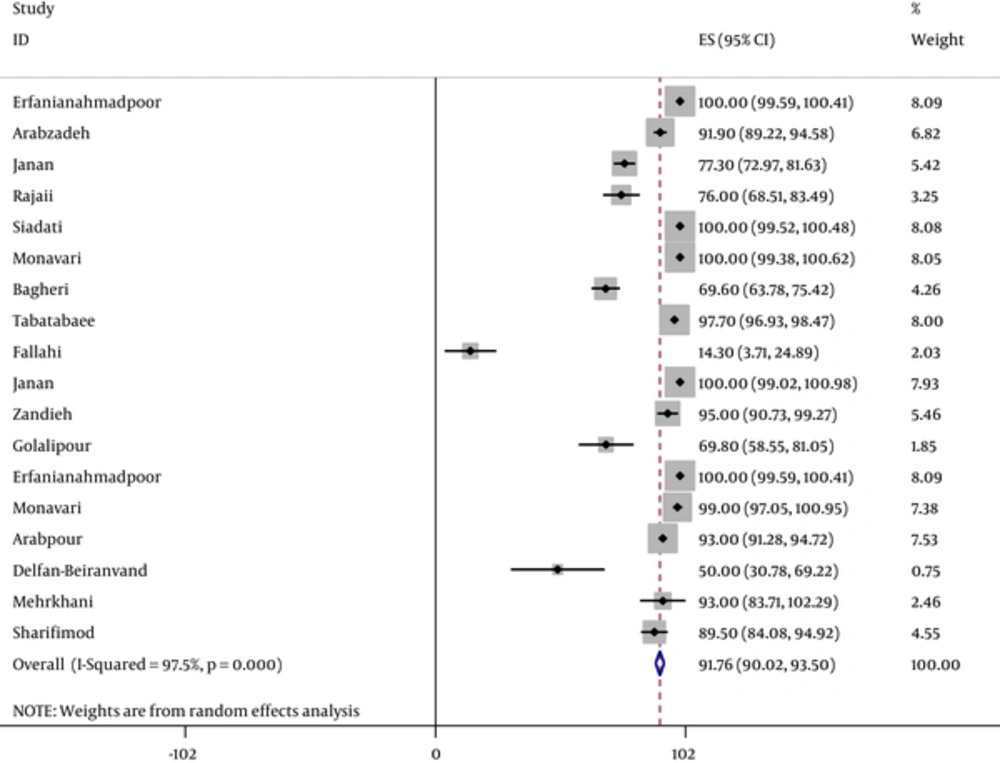

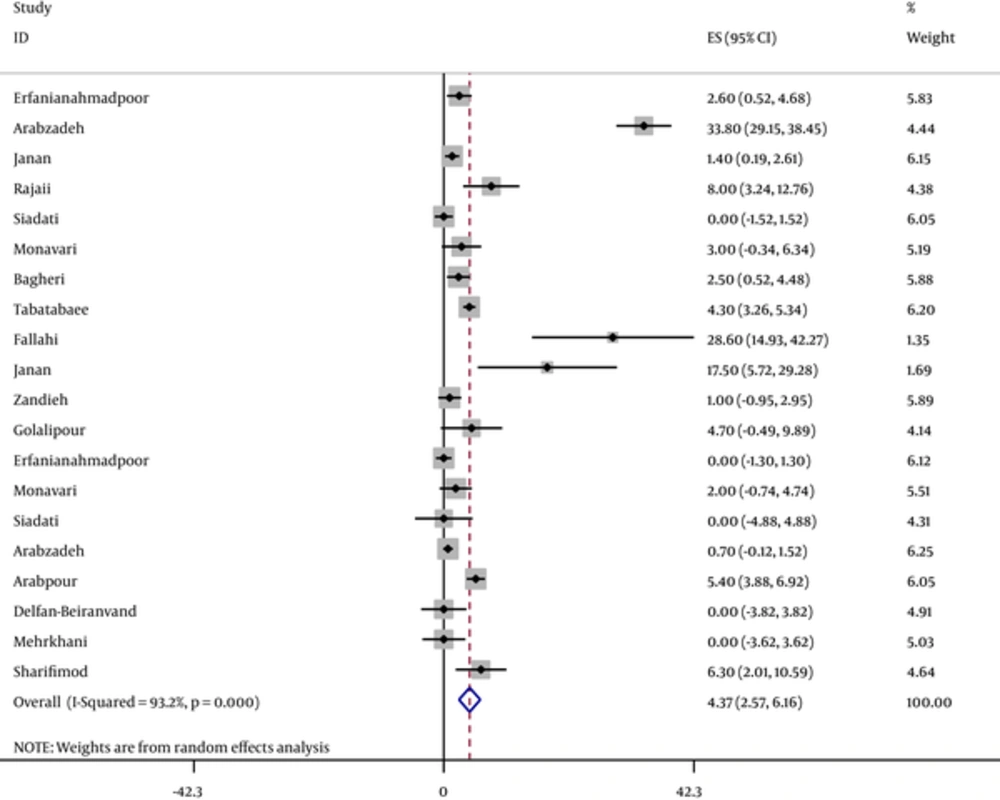

According to the assessment of the heterogeneity, the pooled estimate of IgG, IgM and primary infection seroprevalences of CMV using fixed or random model are illustrated in Table 2. Also, IgG and IgM total seroprevalences of CMV infection per study and pooled estimate are shown in Figures 2 and 3. It should be emphasized that we performed such pooled estimates only when at least four relevant evidences were available. That is why we did not perform meta-analysis for estimating the pooled prevalences of IgG and primary infection among neonates and other subgroups. The results in these subgroups, only systematically reviewed.

| Prevalence by | Sample Size | Pooled Estimate (%), 95% CI, Chi-Squared (Q) | Heterogeneity Test, P Value | Heterogeneity (I-Squared %) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | IgG | 3083 | 92.8 (90.6 - 94.9) | 304.6 | < 0.001 | 97.7 |

| IgM | 3083 | 6.4 (2.8 - 9.9) | 200.5 | < 0.001 | 96.5 | |

| Primary infection | 2594 | 1.1 (0.7 - 1.5) | 9.04 | 0.06 | 55.7 | |

| Infants | IgG | - | - | - | - | - |

| IgM | 738 | 0.6 (0.09 - 1.2) | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0 | |

| Primary infection | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Others women | IgG | 1268 | 78.4 (70 - 86.8) | 345.3 | < 0.001 | 98 |

| IgM | 1268 | 4.6 (1.5 - 7.6) | 39.3 | < 0.001 | 82.2 | |

| Primary infection | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Total | IgG | 4676 | 91.8 (90.02 - 93.5) | 686.4 | < 0.001 | 97.5 |

| IgM | 5089 | 4.4 (2.6 - 6.1) | 279.7 | < 0.001 | 93.2 | |

| Primary infection | 3875 | 1.3 (0.6 - 2.04) | 23.1 | < 0.002 | 69.8 | |

Meanwhile, Sensitivity analysis showed that studies conducted by Erfanianahmadpoor (20) and Tabatabaei (24) had the most influence on the heterogeneity. However, none of these effects were statistically significant.

In the case of heterogeneities among the results, sensitivity analysis was conducted to detect the studies that influenced the heterogeneity most. Because of the remarkable overlaps observed between confidence intervals, no resource was identified for these variations.

4. Discussion

This meta- analysis showed that only 7% of Iranian pregnant women were IgG seronegative. IgM Seroprevalence as well as prevalence of primary infection among pregnant women were 6.4% and 1.1% respectively. Moreover, IgM seroprevalence among neonates was estimated as 0.6%. IgG and IgM seroprevalences among the other Iranian women were high but were lower than those estimated among pregnant women.

Presence of CMV IgG indicates acquiring of infection after birth. This antibody remains in serum protecting the infected person against the next infections (11). Positive IgM is a signal of infection and cooperating with negative IgG indicating a primary infection. Positive serology of IgM and IgG can be due to primary or secondary infections. Distinction between these two types of infection is possible using avidity index of anti CMV IgG. It is so important to distinguish between primary and secondary infections among pregnant women. Diagnosis of CMV IgM is the most suitable index for screening of pregnant women. CMV IgM test can be used to detect the active or recent infection and maybe the best parameter for the diagnosis of the acute infection (24, 30).

CMV IgG seroprevalence among pregnant women in Egypt and Korea were more than that estimated in the current meta- analysis, while the prevalence of IgG among women in Spain, Kenya, Mexico and Malaysia were lower that our estimates (Table 3). IgM seroprevalence among pregnant women in Kenya, Egypt and Malaysia were more than those reported in our study, while these prevalences among Spanish, Korean and Mexican women were lower than those of Iranian women. IgG seroprevalence rate among neonates was not estimated in or study, because of the limited studiesthat entered the current systematic review/ meta-analysis, but two primary Iranian studies reported this prevalence similar to those reported for Chinese, Kuwaiti and Indian neonates (Table 3).

| References | First Author | Year | Country | Group Population | Samplesize | Prevalence of IgG CMV | Prevalence of IgM CMV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (31) | Gonzalez-García | 2014 | spanish | pregnant | 177 | 90.4 | 2.3 |

| (32) | Mainiqi | 2014 | Kenya | Pregnant | 260 | 77.3 | 8.1 |

| (33) | Kamel | 2014 | Egypt | Pregnant | 546 | 100 | 7.3 |

| (34) | Seo | 2009 | Korea | Pregnant | 744 | 98.1 | 1.7 |

| (35) | Alvarado-Esquivel | 2014 | Mexico | Pregnant | 343 | 65.6 | 0 |

| (36) | Saraswathy | 2011 | Malaysia | Pregnant | 125 | 84 | 7.2 |

| (37) | Xu | 1989 | Chinese | Infants | 199 | 90 | 3.5 |

| (38) | Al-Awadhi | 2013 | Kuwait | Infants | 983 | - | 9 |

| (39) | Gandhoke | 2006 | Indian | Infants | 96 | 100 | 18.75 |

| (40) | Abou-El-Yazed E | 2008 | Egypt | hemodialysis | 100 | 98 | 11 |

| (41) | Fowotade | 2015 | Nigeria | HIV-1 seropositive patients | 180 | 93.9 | 11.1 |

| (42) | Ouedraogo | 2012 | french | blood donors | 115 | 92.2 | 12.2 |

| (43) | Njeru | 2009 | Kenya | blood donors | 400 | 97.0 | 3.6 |

CMV infection not only threatens the mother’s health, but also leads to fetal mortality and congenital abnormalities. Therefore, this virus is considered as an important infectious agent during pregnancy so that 10 - 14 percent of fetuses with congenital infection show severe manifestations especially neural complications and hearing loss (11, 44). Type of maternal infection (primary infection or re-infection) is one of the host related factors influencing the mother- to- fetus transmission. overall, the rate of congenital infection due to primary infection is 30% and due to re-infection is 1% - 15% (45).

Generally, prevalence of CMV infection is related to multiple factors such as race, age, sexual behavior, job and socio-economic situation. Because of the remarkable complications of the fetus and neonate, screening of pregnant women in order to diagnose primary or secondary CMV infection is of great importance (46, 47).

A wide range of CMV infection seroprevalences among different countries have been reported. It depends on various factors (11). Most of the pre-school children in Africa and Asia have positive serologies, while less than 20% of American and English children are positive (1). Moreover, both IgG and IgM seroprevalences among women during reproductive age, those with history of spontaneous abortion, immunocompromised women and blood donor women living in Egypt, Nigeria, France and Kenya were more than those estimated in the current meta- analysis (Table 3).

Infection with human cytomegalovirus is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromise individuals transplant recipient, AIDS patients and the newborn. CMV sometimes remains latent in cells and is transmitted with blood products asymptomatically (48).

In screening tests in the Iranian Blood Transfusion Center, blood and blood products are not being examined for CMV. Given the structure and biology of CMV, the transmission of the infection caused by the virus is possible in blood recipients. The problem is particularly important in preterm infants with low birth weight, transplant patients, patients with congenital immunodeficiency, patients receiving immunosuppressants, those with acquired immunodeficiency like AIDS, and thalassemic patients. Further it is recommended to determine the prevalence of CMV antibodies in these patients in order to establish the magnitude of the demand for CMV safe blood (43, 49).

Limitations of the current study can be explained from two aspects. Firstly, defects of the selected studies, i.e. primary, secondary and re-infection prevalences as well as factors associated with CMV prevalence not report in many studies entered this systematic review. Another limitation of our study was related to the low number of eligible primary studies minimized the ability of meta-analysis for all relevant subgroups such as newborns, women in reproductive period, those with history of spontaneous abortion, blood donor women and immunocompromized women who are heterogeneous subgroups but we had to combine them due to the small number of studies within each group. It should be noted that because of the limited eligible studies conducted among men, we emphasized only on the women and neonates in this meta-analysis. It is recommended that in the future studies, in addition to detection of IgG and IgM seroprevalences, primary, secondary and re-infection rates of CMV among the study populations be investigated.

This study estimated the CMV infection prevalence among women and neonates provided evidences for policymakers and decision makers in the field of health with regard to the importance of screening of pregnant or immunocompromized women.

4.1. Conclusion

Our meta- analysis showed that the prevalence of CMV infection among study population is high. Therefore, parts of the mortalities, abnormalities, complications and damages among neonates, women with miscarriage, and immunocompromized women can be related to this viral infection.