1. Background

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy and every gynecologist will encounter it during his/her practice. The exact incidence of endometrial carcinoma in the Middle East countries is unclear, but it is estimated to show a growing trend as do developed countries. In the United States endometrial cancer was diagnosed in an estimated 52,630 women in 2014, with 8590 surrendering to their disease (1). The most common histo-pathological subtype of endometrial carcinoma is endometrioid adenocarcinoma (2).

Patients’ symptoms may be different from abnormal uterine bleeding and vaginal discharge to abdominal or pelvic pain, abdominal distension, early satiety, or change in bowel or bladder function in patients with advanced stages, resembling the ovarian carcinoma symptoms (3, 4).

As in most cases, postmenopausal bleeding is the initial symptom. Approximately 75% of patients are restricted to the early stages at the time of diagnosis and these patients would experience five-year survival rates of about 95%. But as the disease spreads extra uterine tissues, survival decreases to 67% and 23%, for those with regional or distant disease, respectively (5). Unopposed estrogen exposure, late menopause, obesity, nulli-parity, diabetes, estrogen secreting ovarian tumors, polycystic ovarian syndrome, anovulation, and tamoxifen administration have been proposed as risk factors (6-14).

The endometrial carcinoma would spread through different pathways, including direct expansion, free trans-tubal implantation, blood and lymphatic invasion. Lymphatic spread occurs three times more than the blood dissemination. In this manner, malignant cells reach the parametrium, vagina, ovaries and retroperitoneal, pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes (15). Several authors tried to describe recurrence risk factors of endometrial carcinoma. These factors can be divided into uterine and extra-uterine (15). Uterine factors include histological type, grade (16), depth of myometrial invasion (17), cervical involvement (15, 18), vascular invasion (4, 19, 20), presence of atypical endometrial hyperplasia (21), hormone receptor status and DNA ploidy (22). Extra-uterine factors embrace adnexal involvement, intra-peritoneal metastasis, positive peritoneal cytology (23, 24) and pelvic and para-aortic lymph node metastasis (16, 25).

The incidence of positive peritoneal cytology in patients with early stage endometrial cancer has been reported to range from 5% - 10% (26, 27). Based on 1988 international federation of gynecology and obstetrics (FIGO) staging system for endometrial cancer, peritoneal cytology was used as a stage defining variable. According to this staging algorithm, patients with stage I or stage II endometrial cancer who developed positive peritoneal cytology were upstaged to stage IIIA , even in the absence of any other evidence of extra-uterine disease spread (28-30).

Researchers reported that if positive cytology existed as the only manifestation of extra-uterine disease, patients would experience better prognosis than those with adnexal or serosal involvement, which is equivalent to stage III disease (28, 31). In fact these findings suggested that positive cytology cannot predict survival outcomes independently and other clinic-pathological features should be considered as well. However, other investigators have shown that positive cytology is an independent risk factor in both groups of patients with early and advanced stage disease (30, 32-34). Given this uncertainty, 2009 FIGO staging system states that “positive cytology has to be reported separately without affecting the stage” (35).

In this regard, we aimed to investigate the effect of positive peritoneal cytology on prognosis of patients with endometrial cancer. Considering the fact that most studies on this topic were conducted in developed countries, we assume this study would be the first one to conduct on patients in developing countries.

2. Methods

This study was held retrospectively on patients with primary diagnosis of uterine carcinoma referring to Imam Khomeini hospital and Mirza Koochak Khan hospital, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran from September, 2005 to December, 2011.

The institutional review board and ethic committee of Imam Khomeini hospital and Mirza Koochak Khan hospital approved the study protocol. All patients gave informed consent. Patients with diagnosis of endometrioid adenocarcinoma and examination of peritoneal cytology at the time of definitive surgery were enrolled in the study. Patients with prior pelvic irradiation or chemotherapy were excluded. All patients were staged according to the 2009 FIGO staging criteria, after a complete staging procedure (total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic and/or para-aortic lymphadenectomy) and pathological review. Patients were divided into three groups based on their age at initial admission; age < 50 years, 50 to 65 years, and > 65 years. The grade was described as follows: grade I = well differentiated, grade II = moderately differentiated and grade III = poorly differentiated. Lymph node involvement was assessed in patients who experienced recurrence and was coded as positive or negative. Use of adjuvant radiation therapy was collected. Each patient’s specific cause of death was recorded. Survival was calculated as the number of years from cancer diagnosis to the date of death due to the disease.

Patients were followed by means of history and physical examination every 3 month for the first 2 years after surgery, then every 6 month for the subsequent 3 years. Papanicolaou smear and imaging of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were performed twice a year for 2 years, then annually for the subsequent 3 years. All recurrences were biopsy-proven.

Properly powered sample size was calculated to be 200. The chi-square test was used to compare the distribution of demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with positive peritoneal cytology and those with negative peritoneal cytology. Survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between groups were compared using the Enter Method. Cox proportional hazards regression models were developed to examine the effect of positive peritoneal cytology on disease specific survival while controlling for other clinical and demographic characteristics. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software version 20 (Chicago, IL, USA). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

A total number of 220 patients with mean age of 56.3 ± 9.1 years (range: 31 - 81 years) enrolled in the study and 204 were negative for peritoneal cytology (NPC) and 16 showed positive peritoneal cytology (PPC). Demographic and clinical features of the entire patients were as shown in Table 1. When comparing patients with and without positive peritoneal cytology, there were no significant differences in patients’ age at diagnosis (P = 0.737). Patients with NPC were more frequently diagnosed with grade I (91% vs. 9%, P value < 0.05), stage I (98% vs. 2%, P value < 0.001) and stage II (92% vs. 8%, P < 0.0001), and favorable histologic types such as adenocarcinoma (94% vs. 6%, P = 0.028). Also, patients with PPC had more frequently lymph node involvement in recurrence episode (68% Vs 32%, P value < 0.001). Additionally, recurrence was more common in PPC patients (38% Vs 12%, P = 0.031).

| Cytology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels | Overall | Negative | Positive | P Value | |

| Age | < 50 | 95 (43.2) | 88 (43.1) | 7 (43.8) | 0.737 |

| 50 - 65 | 108 (49.1) | 101 (49.5) | 7 (43.8) | ||

| > 65 | 17 (7.7) | 15 (7.4) | 2 (12.4) | ||

| Grade | I | 83 (37.7) | 76 (37.3) | 4 (25.0) | < 0.05 |

| II | 95 (43.2) | 90 (44.1) | 5 (31.3) | ||

| III | 42 (19.1) | 38 (18.6) | 7 (43.8) | ||

| Pathological Subtypes | Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma | 177 (80.5) | 168 (82.4) | 9 (56.3) | 0.028 |

| Papillary | 15 (6.8) | 12 (5.9) | 3 () | ||

| Clear cell/serous | 11 (5.0) | 10 (4.9) | 1 (6.3) | ||

| Carcinosarcoma | 17 (7.7) | 14 (6.9) | 3 (18.7) | ||

| Lymph Node Involvement in Recurrence | Negative | 195 (88.6) | 190 (93.1) | 5 (31.3) | < 0.001 |

| Positive | 25 (11.4) | 14 (6.9) | 11 (68.7) | ||

| Stage | I | 139 (63.2) | 136 (66.7) | 3 (18.8) | < 0.001 |

| II | 51 (23.2) | 47 (23.0) | 4 (25.0) | ||

| III | 24 (10.9) | 19 (9.3) | 5 (31.3) | ||

| IV | 6 (2.7) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (25.0) | ||

| Recurrence | No | 190 (86.4) | 180 (88.2) | 10 (62.5) | 0.031 |

| Pelvic | 12 (5.5) | 11 (5) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Extra pelvic | 18 (8.2) | 13 (5.9) | 5 (2.3) | ||

| > 50 | 55 (44) | 55 (100) | - | ||

Comparison of Clinical and Demographic Variables of Patients with Positive and Negative Peritoneal Cytologya

In 125 patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma of stage I disease, the myometrical invasion of < 50% was seen in 70 patients and 55 were diagnosed with > 50 % myometrical invasion. Interestingly, there were 2 patients with PPC in the first group, but it was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). There were 32 patients with stage II endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

Univariate analysis on patients with endometrioid adenocacinoma revealed that the following variables were significantly associated with survival: stage II (OR = 7.12, 95% CI = 2.95 - 22.10, P value < 0.001), stage III (OR = 8.04, 95% CI = 2.14 - 30.09, P value < 0.001), stage IV (OR=58.09, 95% CI = 13.74 - 245.66, P value < 0.001), recurrence of either intra (OR = 32.65, 95% CI = 12.2-86.7, P value < 0.001) or extra pelvic (OR = 14.54, 95% CI = 4.4 - 47.7, P-value < 0.001), and the number of lymph nodes involvement (OR = 5.59, 95% CI = 2.5 - 12.51, P value < 0.001).

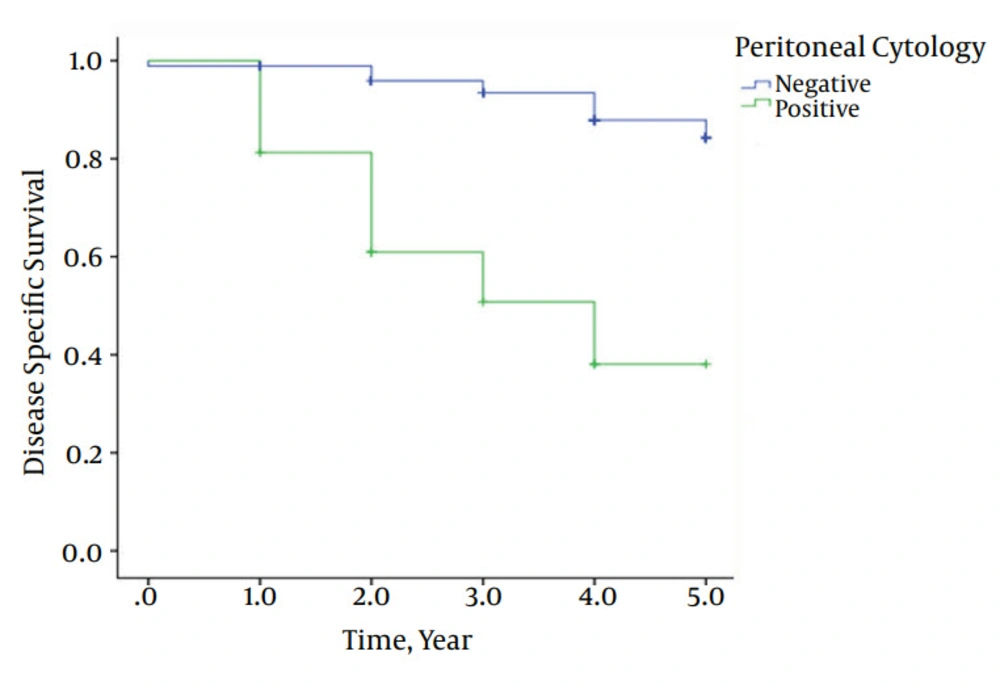

Also, patients with positive peritoneal cytology had a significantly poorer survival compared to those with negative peritoneal cytology: 38% vs. 88% were alive after 5 years, respectively (P value < 0.0001). Mean 5-year survival in PPC and NPC patients were 3.31 years and 4.74 years, respectively (Figure 1).

There were 8 intra-pelvic and 10 extra-pelvic recurrences in patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma (Table 2).

| 5-Year Survival | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levels | B | SE | EXP(B)(OR) | 95% CI for OR | P Value | |

| Lymph Node Involvement in Recurrence | Positive | 1.72 | 0.41 | 5.59 | 2.50, 12.51 | < 0.001 |

| Stage | II | 1.96 | 0.57 | 7.12 | 2.95, 22.10 | < 0.001 |

| III | 2.08 | 0.67 | 8.04 | 2.14, 30.09 | ||

| IV | 4.06 | 0.73 | 58.09 | 13.74, 245.66 | ||

| Recurrence | Intra-pelvic | 3.84 | 0.49 | 32.65 | 12.2, 86.7 | < 0.001 |

| Extra-pelvic | 2.67 | 0.60 | 14.54 | 4.4, 47.7 | ||

| Cytology | Positive | 2.24 | 0.43 | 9.43 | 3.3, 15.2 | < 0.001 |

Associated Factors with Mean 5-Year Survival of Patients with Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma

4. Discussion

Peritoneal washings would be considered positive if malignant cells appeared as the result of trans-tubal dissemination of primary tumor, tumor extension via myometrium/serosal lymphatics, or exfoliation of cells from disease at other extra-uterine sites (30).

Previous investigators reported that malignant peritoneal cytology was associated with an adverse effect on survival, only when other extra-uterine sites of malignancy were present and not if endometrial cancer was still confined to the uterus (30, 32). Others believed that malignant peritoneal cytology is an indicator of aggressive tumor behavior rather than disease spread through peritoneal space (33, 36). On the other hand, the majority of studies have shown the association between malignant cytology and other adverse prognostic features such as high grade disease, non-endometrioid histology, and deep myometrial invasion (30, 37-39).

Our results indicate that positive peritoneal cytology is an independent predictor of survival among patients with 2009 FIGO stage I and stage II endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The survival was found to be significantly worse in patients with PPC compared to those with NPC. However, this finding can be questioned by the fact that most patients in the PPC group might have deep myometrial invasion and this is the reason for poor survival in PPC patients. But the fact that their survival was worse compared to the corresponding patients with NPC provides indirect evidence that positive cytology is indeed an independent prognostic factor in these patients (40). A Special finding in the results which drew our attention was presence of two patients with PPC in group of patients with myometrical invasion < 50%. We do not know the exact pathogenesis of disease spread in these cases, but we assume that blood or lymphatic dissemination could cause disease spread in the peritoneum.

Although a few studies have failed to prove the prognostic significance of positive peritoneal cytology in patients with early stage endometrioid adenocarcinoma (41, 42), most studies especially those with large number of patients have confirmed its significance as an independent predictor of survival (43). In addition, several studies have shown that if peritoneal washing becomes positive for malignant cells, outcomes would be the same in women with endometrial cancer otherwise confined to the uterus, as those women with serosal or adnexal metastasis (37, 44-46). These findings support the idea that patients with stage I/II endometrial cancer who had positive peritoneal cytology should be placed in higher stage groups rather than what has been proposed by current FIGO staging criteria for accurate risk-stratification.

Postoperative adjuvant therapy is another contributing factor in patients’ survival but we are not able to make comment on whether or not the presence of PPC should influence postoperative adjuvant therapy recommendations. Considering the fact that PPC patients were more prone to high-risk or high-intermediate risk features such as non-endometrioid histology, deep myometrial invasion and high grade disease than NPC patients, it would be expected to have this treatment. Future studies could be dedicated to investigation of the exact impact of chemotherapy administration on prognosis of patients with PPC.

Our study has several limitations that must be considered. The major defect of this study was the small number of patients in PPC group.

Similarly, we were not able to determine the factors that separate patients who needed to receive chemotherapy in both PPC and NPC groups, because current guidelines do not indicate chemotherapy in patients with early stages of endometrioid adenocarcinoma.

In conclusion, our study shows that positive peritoneal cytology is an independent prognostic factor in patients with early stage endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Although peritoneal cytology has not been used since FIGO staging criteria 2009, it is still requested by the FIGO to be reported separately. We propound that peritoneal cytology adds back into the surgical staging for endometrial cancer in future FIGO staging criteria revision. Until then, peritoneal washings should stay still as an important part for accurate risk-stratification of patients with early stage endometrial cancer.