1. Background

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide and its incidence rate is increasing, especially in developing countries (1). This malignancy is one of the most common causes of death in women all around the world (2). The mean age of diagnosis in Western countries is around 50 - 60 years and it is accounted the fifth most common cause of cancer related death (3).

As other parts of the world, this malignancy has the first grade among the common cancers in women in Iran and some studies have shown that it occurs in the Iranian women at least one decade younger on average compared to the case in Western countries (4). In addition, breast cancer has the most years lost due to disability (YLD) in Iran, because it develops at lower age and is diagnosed at higher stage (5). Nonetheless, reports imply that survived patients will double by 2030 (6, 7). This might be owing to improvements in diagnostic techniques and general population awareness in this area (8, 9). However, cancer diagnosis and treatment process can affect physical, psychological, sexual and social health of women (8). Treatment completion and cure may be considered as elimination or halting cancer development from physician’s point of view, while it almost conveys several health related problems and worries for the patient and her family. Findings show that the hardest period for women with breast cancer is prior to treatment initiation, and treatment completion (10). For these patients the most important psychosocial stresses is solitude that takes place after definite diagnosis, during the treatment period, and after completing the treatment. Breast cancer patients may suffer from fatigue, nausea, vomiting, appetite loss, diarrhea, acute and/or chronic pain, sleep disorders, oral cavity mucosal wounds, hair loss and reproductive disorders, such as atrophic vaginitis, ovarian dysfunctions, including infrequent or absence of menstruation, sub- fertility, and infertility. Furthermore, as the breasts are counted for sexual arousal and are counted to attractiveness, important part of feminine identity and maternal role, facing a situation that may result in loosing breast may lead to disorders including loss of self-confidence, self-body image damage, alteration of marital relations, sexual enjoyment and depression (11, 12). Reports from limited studies in Iran imply that women with breast cancer attempt to cope with the illness and treatment side-effects by various strategies (13-16). Some patients tend to share their painful experiences and intrusive thoughts with others, seek help from family and friends’ emotional supports or try to find the answers of their questions by asking healthcare providers about their illness to adopt to the illness; whereas, some of them resort to maladaptive responses such as anger, fear, sense of sin, isolation, and even denying the illness and seeking for treatment. However, it is not definitely clear which coping ways are most applied by patients and what kinds are most effective to diminish cancer related disorders to adjust with the situation in the process of the illness (17). Furthermore, different personal characteristics among patients affect confronting their response to cancer diagnosis, acceptance or rejection of the illness, and strategies to adjust with the cancer (18). Coping strategies include efforts those patients apply to eliminate or decrease the impacts of stressful events and achieve adaptation (19). Coping usually is a process from a crisis to adaptation and deals with a stressor. There are two main coping strategies: Problem-focused and emotional-focused. The first involves effective actions for decreasing or amending stressful conditions and the second attempts to regulate the emotional outcomes and affective balance by controlling the emotion resulted from stressful circumstances (20). However, there is this third coping style that identifies unadjusted coping strategies which lead to failure against the tensions, disorder in daily activities and continuous applying, all making the situation to be more critical (21). Thus, being aware of whether each patient has been able to adjust with the stress through wide spectrum of illness, from facing suspicious symptoms, definite diagnosis, treatment and follow up, is necessary for medical staffs to facilitate the recovery and help patients to promote psychological healing (22).

To date, some standardized inventories have been introduced (23-26) and used in several studies to assess coping behaviors in patients with cancer (14, 17, 27-29), but none of them are specific to breast cancer. As evaluation of various aspects of women’s health by standardized and specific instrument is one of the common methods of assessments, being specific and culturally sensitive of each instrument should be considered in every setting appropriately; otherwise, generalizability of the findings might be diminished. According to the variations of coping behaviors among cancer patients with different cultural beliefs, it is necessary to design a specific instrument based on the exploration through deep layers of individuals’ experiences and perceptions. When there is no sufficient or available inventory for this purpose, the researcher needs to design an instrument. Using sequential exploratory strategy is often an elective method, in that researcher gathers and analyze necessary data on the basis of a qualitative approach, design the initial instrument and use it in the target population (30).

2. Objectives

The present study was performed aiming to design and psychometric evaluation of adjustment to illness measurement inventory for Iranian women with breast cancer (AIMI- IBC), as a specific inventory for Iranian women with breast cancer. The final score of the inventory identifies not only coping strategies in women with breast cancer, but also determines the degree of adjustment to the illness. Using this native inventory and analyzing its results in Iranian women population with breast cancer may appear clear understanding for medical staffs of the role of coping strategies in moderating illness outcomes.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

As the aim of this study was to develop an instrument and describe the psychometric properties for identifying coping strategies and measuringthe degree of adjustment to the illness stress, the present study has a methodological and mixed method design. These types of research assess precision of measurements using complex approaches, so that obvious statistical biases are uncommon in these types of studies (31). Moreover, the aim of a mixed method research is not purely simple collecting two qualitative and quantitative studies side by side, but it is to integrate and mix, connect, and consolidate both of them (30). This research had a sequential exploratory mixed method design that researchers’ concentration was mainly on the qualitative data rather than the quantitative and integration performed in the interpreting of the findings. In this manner, the research team performed mixing the data in the commentary stage, so that judgment and decision making of perseveration of the items, constructs and measurement factors of adjustment to breast cancer, were done fundamentally on the basis of the qualitative findings while quantitative approach lead to omit or amend some items, those generated in the qualitative stage. However, findings of the quantitative stage were used to confirm and support defined constructs resulted from qualitative stage.

The first stage of our study had a qualitative approach with a phenomenology design. The purpose of the phenomenology qualitative study is to exploring the lived experiences of human kind from environs’ phenomena. The second stage, using findings obtained from the first stage, the study instrument was developed and the psychometric properties were described.

To develop the instrument, we utilized guidelines recommended by Waltz, Strickland and Lenz, a norm-referenced approach, including identification of a conceptual framework to describe the aspects of measurement process, identification of measurement objectives, pathway designing and instrument (32).

3.2. Participants, Sampling and Data Gathering

Our participants were a sample of Iranian women with breast cancer whose treatment process was completed during the past year and attended the oncology ward for treatment follow up located in Shohada-e- Tajrish hospital, a referral educational cancer treatment affiliated to Shahid Bheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran. In addition, for maximum variation to yield better transferability of data, purposeful sampling was done from a private hospital in Tehran from an oncology clinic with eligible women from any age groups and different socioeconomic characteristics.

Inclusion criteria for the two stages of the study was as follows: Iranian women if they were informed of their definite primary breast cancer diagnosis with non-metastatic illness, if they did not disclose any kind of psychological illness during past six month, if they did not confront any crisis except for the breast cancer diagnosis/treatment during past year, if they speak Persian language and if they had undergone any type of cancer treatment such as surgery( mastectomy or lumpectomy) and/or chemo radiation during past years. As there is no definite criteria for describing sample size in the qualitative studies (33) and our inquiry had a phenomenology design, we sought to gather the rich and unique data from women’s experiences as they were lived and even might be emerged once from statements (34). So we did not seek the repeated pattern of data, rather explored experience through life stories that provided us the opportunity of obtaining insight into certain aspects of the phenomenon, adjustment to breast cancer, which we had chosen to study.

Data gathering for the qualitative stage lasted from November 2014 until February 2015. In the first stage, qualitative inquiry, in-depth interviews using open-ended questions were performed by the first researcher with eligible women in a private room in both hospitals. Each interview was digitally recorded (except for two of them because interviewees did not content to voice recordation), transcribed verbatim and analyzed before the next interview. Research questions comprised central and follow up questions. The central question was dominantly asking each participant to give direct description of her experience as it was: “Could you please describe the experience of coping with breast cancer as much as possible the way you live through it?” As the interview process went on, the researcher asked participants to share their thoughts, feelings, sensations and memories by follow up questions.

As we asked what an experience it was like, it should be remain very concrete. In this way, probing questions such as “Who said that?”, “How did you feel?”, “ what did you do then?” or “What happened next?” etc. Writing field notes and memos, as important data sources, were done during interviews to produce greater meaning and better understanding of the phenomenon and social situation. Interviews were continued until findings indicated no new or different data obtained from them. Each interview lasted approximately 45 to 60 minutes. Finally, 28 interviews were conducted with 28 participants, and considering 4 complementary interviews 32 interviews were totally documented.

In the second stage, the psychometric evaluation of AIMI-IBC needed to be carried out in a quantitative approach. After item generation and instrument development from qualitative stage of the study, final sample size was calculated based on the number of items of the instrument, considering 10 percent attrition rate. As a 78- item AIMI-IBC needed to be validated in several steps, the items of the initial draft were reduced through these processes; consequently, the amended version of AIMI-IBC comprised 54 items before construct validity indicating coping strategies of Iranian women with breast cancer. In this stage, a sample of 340 women with breast cancer according to the inclusion criteria indicated earlier in the qualitative stage were recruited using a convenience sampling from eligible women from Shohada-e- Tajrish and Imam Hossein Hospitals( two referral public hospitals affiliated to Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences) and a private hospital in Tehran. Data collection occurred from April through June, 2015 following written consent obtained from participants. The initial instrument was developed in three domains by including Likert-type, ordinal scale with 5 possible responses from “always” to “never” for the 41 first items, and rated from “strongly agree” to “ strongly disagree” for 42 -54 items. The instruments were self-completed and in case of illiteracy, data was collected using interview with participant by the first researcher.

3.3. Data Analysis

Several approaches were applied to analyze the data. Content from the interviews were examined using thematic analysis and hermeneutic phenomenology was employed to explicate the core essences as experienced by the women and described through their experience. This approach is applied in almost all research area including medical science and is an interdisciplinary method to uncover the better understanding of a phenomenon. In addition, hermeneutic phenomenology is the art of interpretation of the narratives in the text (35). As adjustment to illness might be a subjective experience realized by an individual and depends on the cultural context where it happens, efforts should be done to obtain the genuine objective nature of the things by the women through their life stories. In this approach the focus was on the way that phenomenon, adjustment to the illness, appeared to researchers through lived experience and they aimed to provide a rich textured description of its own right. On the other part, since the item generation of the study’s instrument was based upon the inductive-deductive approach, the conceptual framework, extracted from review of literatures included some aspects of Lazarus and Folkman’s theory of stress and coping used to explain each of the coping strategy and adjustment domains.

Data gathering and analyses were conducted simultaneously, and, as the initial coding was done, then, subsequent interviews were conducted. The transcriptions were read constantly to recognize statements that seemed particularly essential and that could reveal the main concepts through the narratives. For data management, MAXQDA software was used. Trustworthiness of qualitative data was established based on the Guba and Lincoln criteria (36) in each step of the first data collection and/ or analysis as shown in Table 1.

| Criteria | Techniques | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Credibility (internal validity) | Checking | Reflexivity | |

| - member checking | researcher’s background and position | Prolonged engagement | |

| - peer checking | self-aware analysis | Persistent observation | |

| searching for disconfirming evidence | Triangulation: public vs. private hospitals | ||

| Transferability and Fittingness (external validity) | Rich descriptions | Varied sample population: different socio-demographic characteristics with different treatment methods | |

| Conformability (objectivity) | External checking and Expert audit review | audit trail: raw data, written field notes, data synthesis and structure of categories and themes | |

| Dependability (reliability) | External audit: data collection, data keeping and data accuracy | Code-recode strategy: two weeks interval | |

The validity and reliability of the initial draft of instrument in the second stage of research were performed in several steps to perform psychometric evaluation of the instrument:

3.3.1. Face Validity

Both qualitative and quantitative methods were applied to assess face validity consisting of 20 eligible women with primary breast cancer. In qualitative face validity, they were randomly selected and asked to individually assess the instrument’s items whether the descriptions were clear, fluent and easy to understand. Furthermore, for quantitative validity, the impact score of each item was calculated to determine the importance of each item (frequency × importance). It was estimated based on the mean score of the item’s importance and percentage of participants who rated the item as important (4) or very important (5). Items were considered appropriate if they had an impact score equal to or greater than 1.5. In this step (31), all items were retained due to high scores and none of them was eliminated.

3.3.2. Content Validity

As selection of at least 5 experts is adequate for assessment of the content validity of a questionnaire (37), the instrument was given to 15 experts in the specialties related to the domain of the study. In the qualitative step, firstly, the experts evaluated grammar, the language and definitions, wording, the scoring criteria and the timing of questionnaire completion of the instrument. In the quantitative step, secondly, the content validity ratio (CVR) and the content validity index (CVI) were calculated according to Waltz and Bausell’s criteria. For CVR calculation, the answers were designed with responses Likert-scaled from 0 to 3. (necessary, useful but not necessary, and not necessary). For CVI calculation, relevancy, clarity and simplicity of each item was examined by experts based on four-point scale (32).

3.3.3. Construct Validity

To identify the constructs of the latent draft of AIMI-IBC, exploratory common factor analysis was done. The appropriateness and significance of data factor analysis was examined using Bartlett’s Test and Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin and the number of factors was determined using principle component analysis with varimax rotation and visual scree plot. In this analysis, if association between each item and a factor was 0.30 to 0.50 (factor loading), indicated a salient association and considered to stay (38). Individual items that loaded on more than one factor were discarded or in case of importance and necessitywere allocated in the factor with higher association.

3.3.4. Inventory’s Reliability

Finally, the instrument’s internal consistency was examined applying Cronbach alpha. Items with association coefficient ≥ 0.70 were considered acceptable. Furthermore, test-retest stability for the overall instrument and for each factor was estimated using an interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with a value of ≥ 0.80 by participation of 20 eligible women randomly selected who completed the instrument twice with 10 days intervals (39). Data analysis was performed using SPSS software package (version 21; SPSS Inc.).

3.4. Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by ethics committee of the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (ethical code: sbmu2.rec.1394.23). All patients provided their written consent to enter the research and reassured that participation was voluntary, and anonymity and confidentiality would be guaranteed. Interviews were stopped based on participants’ willingness or emotional situation, and continued when they chose. In addition, they were allowed to discontinue the participation at any time they intended.

4. Results

4.1. Phase 1(Qualitative Stage)

4.1.1. Study’s Participants

In the qualitative stage, 28 eligible women completed the study who were 32 - 68 years old (mean = 50 ± 7.88). Some of socio-demographic characteristics of the quantitative study participants are shown in Table 2.

| Characteristic | Phase of Study | |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | Quantitative | |

| Age | ||

| 28 - 45 | 6 ( 21.4) | 112 (32.9) |

| 46 - 60 | 18 (64.3) | 188 (55.3) |

| 61 - 73 | 4 (14.3) | 40 (11.8) |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 2 (7.2) | 40 (11.8) |

| Less than high school | 5 (17.8) | 126 (37.1) |

| High school | 10 (35.7) | 142 (41.7) |

| College and post college | 11 (39.3) | 32 (9.4) |

| Employment status | ||

| Housewife | 18 (64.2) | 265 (77.9) |

| Official employed | 9 (32.2) | 36 (10.6) |

| Self-employed | 1 (3.6) | 8 (2.4) |

| Laborer | 0 | 27 (7.9) |

| other | 0 | 4 (1.2) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 1 (3.6) | 20 (5.9) |

| Married | 24 (85.7) | 296 (87.1) |

| Other | 3(10.7) | 24 (7.1) |

| Residence | ||

| Capital (Tehran) | 14 (50) | 246 (72.8) |

| Other | 14 (50) | 94 (27.2) |

| Housing tenure | ||

| Home owner | 16 (57.1) | 136 (40) |

| Tenant | 10 (35.7) | 170 (50) |

| Other | 2 (7.2) | 34 (10) |

| Whole coverage health insurance | ||

| Yes | 18 (64.3) | 104 (30.6) |

| No | 10 (35.7) | 236 (69.4) |

| Monthly family income (income percentile) | ||

| Less than poverty line | 3 (10.7) | 142 (42.7) |

| 25 to 50 percentile | 11 (39.3) | 131 (38.5) |

| 50 to 75 percentile | 9 (32.1) | 55 (16.2) |

| More than 75th percentile | 5 (17.8) | 9 (2.6) |

| Method of surgery | ||

| Mastectomy | 22 (78.6) | 204 (60) |

| lumpectomy | 6 (21.4) | 136 (40) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

4.1.2. Emerging Themes and Item Generation

After initial coding, final codes and main concepts were extracted, respectively. Then, similar themes were clustered. Categories and themes were emerged based on the codes with similar meanings. In total, 3 key themes, 17 conceptual categories and 55 sub-categories created that manifested as coping strategies of adjustment to breast cancer (Table 3).

| Theme | Conceptual Category |

|---|---|

| Collision of feelings | Confronting |

| isolation | |

| Fatalism | |

| Role wasting | |

| projection | |

| Feeling of guilt | |

| Anxiety | |

| Fear | |

| Avoidance | Abstention |

| Diversion | |

| Logical endeavor | Cognitive acceptance |

| Threat control | |

| spirituality | |

| Positivism | |

| Maturation | |

| Role preservation | |

| support |

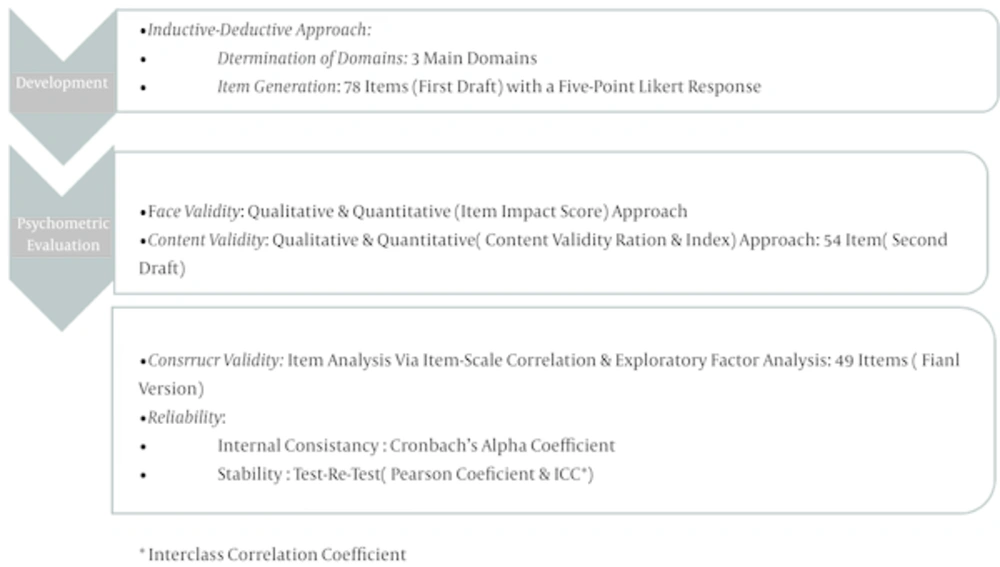

Finally, after identification of the main domains, item pool generation was perfomed. Items were created based upon mainly data obtained from interviews and partly the literature review. Item pool containing 78 items were generated and used for psychometric evaluation. Details of development and psychometric evaluation of the AIMI-IBC are shown in Figure 1.

4.2. Phase 2 (Quantitative Stage)

4.2.1. Study’s Participants

For the quantitative stage, 340 women met the inclusion criteria entered the study and completed the questionnaires. Inclusion criteria of participants for this phase were similar to the first one. The participants’ characteristics are compared in Table 2.

As responding to the questionnaires was quietly under supervision of the researcher, in case of ambiguity or any question, she was accessible to explain and clarifying the item(s) to responders. Therefore, the response rate was 100 percent. In both stages of the research, most of participants were married and living with spouse; burgess, Muslims, housewives and treatment method was mastectomy plus chemo radiation.

4.2.2. Face and Content Validity

For all item impact scores were calculated and the least score was 1.5. So that, all items were saved in this step. In addition, for 3 items due to the misunderstanding of two participants, structure of those statements was amended and reworded to the simple form.

Both qualitative and quantitative content validity examination was conducted for the first draft of instrument by 15 content experts: in the qualitative evaluation, 12 items were discarded due to redundancy of content and poor grammar/wording. Then the remainder items were reworded to increase clarity of items. In the quantitative examination of the remaining 66 items, 13 items with CVR less than 0.6 and CVI less than 0.7 were removed based on Lawshe (36) proposed for panel sizes of 10 and above and Polit and Beck’s advice for items adequacy, respectively (32). Instead, one item was added to the items of the conceptual category of “role preservation” due to the expert opinions. Therefore, the second draft of AIMI-IBC consisted of 54 items remained in.

4.2.3. Construct Validity

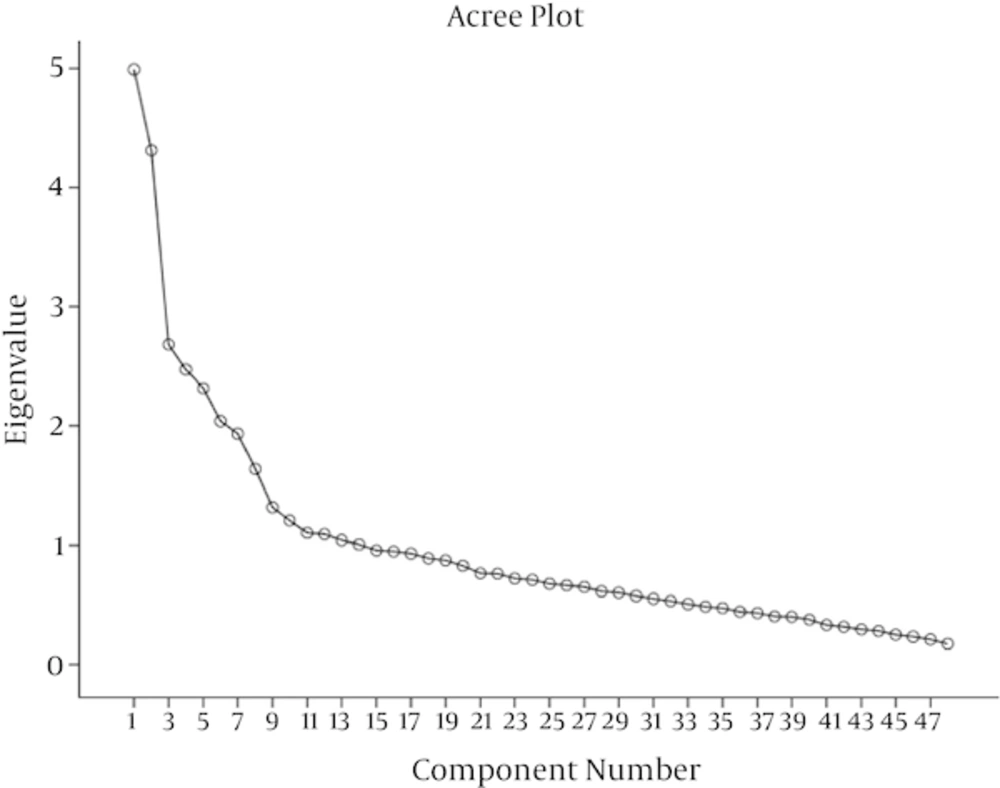

In this step, scaling properties of the instrument was tested using exploratory factor analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test confirmed that the data was appropriate for factor analysis (KMO index = 0.74, χ2 = 4837.67, P < 0.001).Item analysis was conducted based on the principle component with varimax rotation.

The result of this analysis identified 10 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, satisfying scree test and factor loading equal to or greater than 0.3 accounting for 59.1% of variance observed. The outcome of this step led to discarding 5 items (4 from support and one from positivity) and resulted in 49 items and 10 categories organizing the final version of AIMI-IBC (Table 4). Furthermore, the scree plot suggested ten factors should be extracted as Eigen values greater than one. The scree plot (Figure 2) shows the variances explained by each factor in the factor analysis and determine the number of factors to retain. It should be noted that none of the concepts and categories were removed, but merged in the similar clusters as the components of the scale.

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | Factoer7 | Factor 8 | Factor 9 | Factor 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative variance percent | 8.77 | 15.05 | 20.14 | 25.12 | 29.61 | 33.42 | 37.05 | 40.56 | 49.39 | 51.90 |

| 1: I feel irritable and impatient | 0.396 | |||||||||

| 2: I feel loneliness | 0.45 | |||||||||

| 3: I feel sinfulness | 0.876 | |||||||||

| 4: I blame myself | 0.754 | |||||||||

| 5: I have regrets that I was not grateful for everything that I had | 0.655 | |||||||||

| 6: I believe I am being punished for my sins | 0.564 | |||||||||

| 7: I believe that others and community are culpable | 0.664 | |||||||||

| 8: I try to sleep all the time | 0.593 | |||||||||

| 9: I avoid thinking about my illness | 0.827 | |||||||||

| 10: I amuse myself with pleasant diversions | 0.759 | |||||||||

| 11: I except a miracle changes the situation | 0.739 | |||||||||

| 12: I do not take my illness serious | 0.526 | |||||||||

| 13:I pretend that nothing has happened | 0.599 | |||||||||

| 14:I try to handle illness like similar patients | 0.531 | |||||||||

| 15:I try to spend much time with my family | 0.63 | |||||||||

| 16: I try to do my duties as a mother/wife in a good manner | 0.542 | |||||||||

| 17: I try to seek more information about my illness | 0.435 | |||||||||

| 18:I accept others’ supports | 0.814 | |||||||||

| 19:I try to get information from my physician | 0.828 | |||||||||

| 20:I re-organize my daily life | 0.51 | |||||||||

| 21:I try to improve my mood | 0.301 | |||||||||

| 22: I am optimistic | 0.526 | |||||||||

| 23: I do my best to achieve recovery | 0.55 | |||||||||

| 24: I try to defeat the illness | 0.722 | |||||||||

| 25: I am hopeful I am cured | 0.642 | |||||||||

| 26:I express my feelings to my family/friends | 0.567 | |||||||||

| 27: I pay more attention to my nutrition and physical activity | 0.83 | |||||||||

| 28:I am worried what to do | 0.701 | |||||||||

| 29:it’s hard to accept reality | 0.769 | |||||||||

| 30: I can’t cope with the cancer | 0.653 | |||||||||

| 31: I still feel shocked | 0.647 | |||||||||

| 32:I feel so upset | 0.304 | |||||||||

| 33: I can’t concentrate on my thoughts and feelings | 0.656 | |||||||||

| 34:I am fearful more than before | 0.836 | |||||||||

| 35: I am worried about worsening my illness | 0.644 | |||||||||

| 36: I’m really worried about my future | 0.757 | |||||||||

| 37: I am worried about my family’s future | 0.707 | |||||||||

| 38:My everyday life has become deranged | 0.769 | |||||||||

| 39: I feel I have lost my beauty of appearance | 0.471 | |||||||||

| 40: I am afraid of having sex with my spouse | 0.438 | |||||||||

| 41: I am worried I might be dependent on others | 0/808 | |||||||||

| 42: I have become more dependent on my family for daily life | 0.479 | |||||||||

| 43: I pray for my healing | 0.558 | |||||||||

| 44: I trust on the power of God | 0.819 | |||||||||

| 45: I believe it is God’s will | 0.619 | |||||||||

| 46:I look at it as an opportunity for compensation | 0.716 | |||||||||

| 47: I believe that the situation might be more terrible than now | 0.33 | |||||||||

| 48: I often want to be alone | 0.706 | |||||||||

| 49: I surrender to destiny | 0.76 |

4.2.4. Inventory’s Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha was used for calculating the internal consistency coefficient of the final version of AIMI-IBC. The alpha of 10 factors ranged from 0.78 to 0.87 confirming all factors were internally consistent (Table 5). The test-retest reliability for the scale’s stability was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Outcome of this procedure indicated that the scores of all factors and the total scores of the scale were highly correlated within a two week interval testing (r = 0.87 - 094 and 0.91; P < 0.001).

| Factor | Rotated Component Loadings | Item | Cronbach’s Alpha Coefficients | Eigenvalues After Rotation | % Explained Variance | Cumulative, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Feeling of guilt | 6 | 0.87 | 4.21 | 9.77 | 8.77 |

| 2 | Abstention- Diversion | 6 | 0.78 | 3.01 | 6.27 | 15.05 |

| 3 | Role preservation and | 6 | 0.86 | 2.44 | 6.09 | 20.14 |

| seeking support | ||||||

| 4 | Efforts for threat control | 8 | 0.85 | 2.38 | 5.97 | 25.12 |

| 5 | Confronting | 6 | 0.79 | 2.15 | 5.89 | 29.61 |

| 6 | Fear and anxiety | 4 | 0.84 | 1.82 | 5.49 | 33.42 |

| 7 | Role wasting | 5 | 0.8 | 1.74 | 4.62 | 37.05 |

| 8 | Maturation and growth | 5 | 0.83 | 1.68 | 4.5 | 40.56 |

| 9 | isolation | 1 | Not calculated | 1.5 | 3.13 | 49.39 |

| 10 | fatalism | 1 | Not calculated | 1.45 | 3.02 | 51.9 |

4.2.5. Formal Inventory

The researcher requested four experts to generally check and amend the names of the obtained factors. The final components of the scales are shown in Table 5.

In summary, the AIMI-IBC is divided into 10 factors which form sub-scales, with a total of 49 items. Mean subscale scores (range 1 - 5) of the positive AIMI-IBC items were calculated with higher scores indicating higher adjustment. The higher the scores achieved in factors 3, 4, and 8 represented, the higher is the rate of adjustment , but the higher the scores obtained in factors 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 10 represented, the lower is the adjustment with the illness. In other word, higher scores for negative or reversed items including 1 to 15, 19 to 24 and 37 to 45, indicate lower adjustment or mal -adaptive coping behaviors. In total, maximum expected score for all items of the scale is 245 and the minimum is 49. The discriminating value for this scale is 122.5 that was calculated based on the mean score of respondents’ answers, as respondents with mean score equal to 122.5 and above are accounted for higher adjustment with the illness and respondents with mean score lower than 122.5 are considered to be not enough adjusted.

To summarize, for the AIMI-IBC components all patients comparisons were not statistically and significantly different, whereas the mean score of respondents with mastectomy were significantly lower than of respondent with lumpectomy.

5. Discussion

AIMI-IBC appears to be a valid and reliable scale that can be used for evaluation of coping behaviors and adjustment assessment in Iranian breast cancer patients. Attention to and evaluation of coping with illness and degree of adjustment in the oncology wards are still major psychological needs that are often ignored by health professionals in most public hospitals in Iran. Whereas breast cancer women need to explore their own concerns and emotional needs, coping strategies to deal with the situation, and how these issues influence their adjustments to the illness.

This study benefited from explicit patients’ experiences and experts’ opinions to generate concepts and form items in the initial item pool from the beginning of the development process. This approach reassured that the present scale covered several aspects of deep experiences of coping strategies in women with breast cancer to achieve adjustment with their illness. Several steps of item analysis ensured that only the most relevant items were included in the final scale.

Results from face and content validity techniques were either based upon the related literature review, or on the in-depth interviews with patients and experts reviews. In addition, evidence supporting the exploratory construct validity confirmed that 10 components of adjustment with breast cancer in Iranian women categorized into a 3- dimensional model including, collision of feelings, avoidance and logical endeavor. The rationale used for naming the three main categories was partly guided by Lazarus’ conceptualization of coping stress (19) and multi-dimensional assessment of coping recommended by Endler and Parker (40). The hypothesized categories were defined and named before the analysis. The main difference between AIMI-IBC and other common coping scales are as follows: First, most of them such as WCQ (Ways of coping questionnaire), COPE (coping operations preference enquiry) or CISS (coping inventory of stressful situation) is specifically designed for adjustment for breast cancer and do not consist of items related to the physical aspects of breast cancer influencing mental adjustment such as “body imagination” and “sexual function” after mastectomy and chemotherapy, rather they are used to assess the coping strategies in general stressful circumstances. Secondly, although, WOC-CA (ways of coping with cancer) and mini-MAC (mini mental adjustment to cancer) have been commonly used for cancer patients, these inventories mainly assess emotional and Escape-avoidance coping ways pf patients as mal-adaptive adjustment to variety of cancers and lacked some main planned problem solving solutions such as seeking social support and self-controlling.

Third, the present study’s scale evaluates not only coping strategies women use in response to the illness, but also measures either degree of adjustment (rate of adjustment) or situational and dispositional coping efforts in Iranian women with breast cancer. Since a designed native inventory in a specific country with an exclusive cultural norms might reflect those community’s language and culture, using such an inventory in other communities even with precise translation may lead to non-sensitive and accurate findings because of the differences in content’s appropriateness of items.

The fact of Factors 1, 6, 9 and 10 were somewhat similar to the contents of coping behaviors instruments (23, 24, 26, 40, 41) that are combination of original concepts of the “feeling of guilt,” “projection”, fear”, “anxiety”, isolation”, and “fatalism” that indicate the main theme ,”Collision of Feelings”. According to Lazarus and Folkman, emotion-focused coping styles as a global category are more likely occur in uncontrollable conditions like cancer than in controllable situations (19). Most of patients perceived themselves outside their control and had no power to stop it.

The contents of Factor 5 “Confronting” deal with uniquely to emotional-focused responses such as uncertainty, consternation and depression , that patients face by cancer diagnosis for the first time; whereas, in other instruments have not addressed these responses as separate factors and are grouped in the mal-adaptive coping ways. The emphasis on this emotional response is because the following reactions and coping behaviors as initial appraisal of the situation result from definite cancer diagnosis can shape patients’ adjustment and living with cancer.

Unlike a number of cancer coping assessment instruments (23, 26), this instrument was found to have a factor named “Abstention- Diversion”, Factor 2 , including 6 items cover the concept of deliberate forgetfulness, avoidance and mental / behavioral disengagement with the problem. This factor was entitled “Less useful” coping responds to stress in the COPE scale (24). However, this concept was not distinct from other emotional focused coping components, so it was embedded in the disengagement factor that might reflecting the general coping tendencies in variety of stressful situations.

Factor 7, Role Wasting,” was unique to this instrument and not found in other coping assessment scales as a distinct factor. This component indicates to the losing the known feminine, maternal and conjugality role in the given community. Perceived beauty of appearance lost and traditional role of maternity have been shown as main findings of related studies specifically in women after mastectomy and in young ones (13, 42, 43). That is why this component was not combined to the other factors in the “collision of feelings” due to its own factor loading and good variance. Bodily changes after breast cancer treatment may lead to emotional distress and derange woman’s ability to adjust to the new situation.

Factor 3, “Role preservation and seeking support”, was found to consist of “role preservation” and “support" of the “Logical endeavor” domain. Seeking social support by respondents in a stressful situation is similar to other coping assessment scales (23, 24, 26), but “Role Preservation” is a unique finding that was extracted within a few, married, employee and older women in this study. It is the opposite of the "Role wasting" found in the study and imply to efforts to retain the prominent role a married woman, maternal role, indicating an active coping with existing distress including, doing conjugal tasks and dealing with the children, married life or going back to their job.

The contents of Factor 4, “Efforts for threat control” was found to be very different from the contents of a comparable factor in aforementioned coping instruments. This component was extracted by combination of “Positivisms” and “Cognitive acceptance” that refer to the control of the illness recurrence and its risk factors using risk reduction efforts. Approximately, all of responders mentioned the odds of cancer metastasis and/ or recurrence and necessity of changing previous risky behaviors to the healthy life style. No other coping measurement with cancer instrument was found to have a similar factor.

The 8th and final factor, ”Maturation”, as independent factor similar to other coping behavior scales was found. This component is a combination of two of the domains, “Spirituality” and “Growth”, which were emerged by in-depth interviews with patients. The role of spirituality in well-being has been shown in several studies (44-46) and is accounted for a positive emotional-focused coping strategy in some of the coping assessment scales (24, 26, 41). The prayer and worship are the important stress coping strategies that influence social life. Koolaee et al reported that stress management increased quality of life in breast cancer patients and their assertiveness and can help the patients to replace negative thoughts with rationality (47). Almost all patients in this study resort to the typical spiritual and religious practices such as meditation and prayer that were capable to better adjust with the illness. They also divulged that cancer gave them an opportunity to searching for a meaning of life, made them appreciating the God’s gifts and lead to strengthening their religious beliefs.

5.1. Conclusions

The fact that construct and content validity, and the reliability of the scale were found to be satisfactory suggest the AIM-IBC is a psychometrically valid and reliable inventory for measuring Iranian adjustment to the breast cancer. This instrument is unique in that it contained factors and items specific to the context of the Iranian women culture. The study’s instrument took the patients approximately 15 to 20 minutes to complete it.

This study has presented the usefulness of the 10- factor 49-item AIMI-IBC as a measure of coping in Iranian breast cancer women and provides support for utilizing this instrument in future studies to understand ways of coping in women with breast cancer. Future researchers can be conducted based upon this research by further applying this instrument in a similar population in Iran.