1. Context

1.1. Incidence of PABC

In Iran, breast cancer is the most frequent cancer and the fifth cause of death due to malignancies with about 8,500 incident cases per year. Iranian women, when being diagnosed with breast cancer, are at least 1 decade younger than the developed countries (1). The most common cancer in pregnancy and the most common cause of cancer-related death in pregnant and breastfeeding women is breast cancer (2, 3). Statistically, 1 case occurs per 3,000 pregnancies (4).

The incidence of breast cancer in pregnancy is increasing, largely due to delayed pregnancy by the middle age. Throw the average age of the conflict is 32 to 34 years (4, 5). Pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) is a case of breast cancer that occurs during pregnancy or up to 1 year after delivery. It is epidemiologically uncommon and accounts for about 0.2% to 3.8% of all breast cancers (5, 6). It is noteworthy that these cancers are generally worse in prognosis and they are often associated with the axillary lymph nodes metastasis and larger tumor size in diagnosis, possibly due to delay in detection (7). According to previous studies, the prevalence of PABC among mothers who were first pregnant after 30 years was 2 to 3 times that of the number of mothers who gave birth to their first children before the age of 20 (7). Common PABC differential diagnoses include fibroadenoma, lactation adenoma, galactocele, and fibrocystic changes. Rarer differential diagnoses are lymphoma, leukemia, and sarcoma.

2. Evidence Acquisition

We reviewed several published papers on PABC and imaging modalities in PABC by searching the medical and health databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, as well as clinical trials.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Manifestations

One of the most common causes of the referral of pregnant and lactating patients to breast clinics is mass or nodularity sensation. During this period, due to hormonal changes, the volume of fibroglandular tissue, as well as the volume of water and blood supply increases; so, breast nodularity in the clinical examinations can make difficulties for both clinical diagnosis and interpretation of different imaging techniques. Nodularity sensation by a physician or patient that lasts more than 2 to 4 weeks should be seriously taken and necessitates the use of imaging techniques (8). The most common manifestation of PABC is a painless mass discovered by the physician or patient (4, 9). Other symptoms include unilateral breast enlargement accompanied by skin thickening, localized pain, and nipple discharge with or without mass or erythema, or even with distant metastasis and local invasion (10, 11). In some patients, a less common finding called milk rejection occurs; it means the infant is reluctant to eat milk from the affected breast. One of the rare symptoms is bloody discharge (12, 13). Histopathology: The most common PABC pathology in the time of diagnosis is high-grade ductal carcinoma with a high incidence of lymphovascular invasion (14). These tumors are mostly positive hormone receptors (estrogen and progesterone) compared to those with similar age and non-PABC. Only 30% of PABCs are HER2-positive (14, 15). However, in some studies, there is no significance between PABC and non-PABC in the prevalence of hormone receptors, p53, and HER2 (16).

3.2. Imaging Modalities

3.2.1. Ultrasound

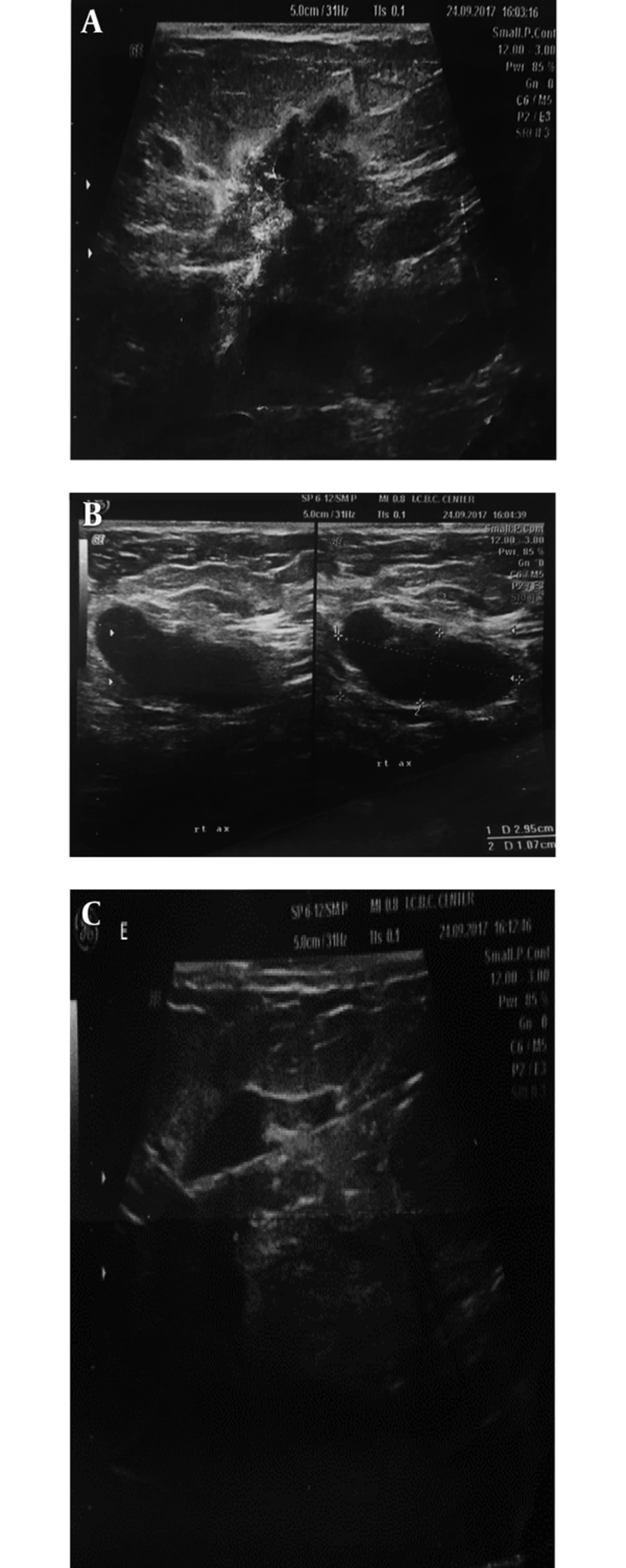

Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of PABC has a high sensitivity and specificity (17). The first step in dealing with pregnant and breastfeeding patients with a sense of mass is ultrasound. Since in this phase the nodularity of the breast tissue increases, any sustainability nodularity that lasts at least more than 2 to 4 weeks requires a Target ultrasound. In similar studies, the sensitivity of ultrasound to detect PABC has been reported to be up to 100% with a negative predictive value of about 100%. In another study, sonography was abnormal in 100% of symptomatic patients (11). Any suspicious mass found in ultrasound should subsequently be subjected to an ultrasound-guided biopsy. If the pathology is malignant, it is necessary to carefully examine the contralateral breast, as well as the multifocal or multicentric lesion in the same breast. It should be noted that PABC is more likely to be locally advanced. Another application of ultrasound in the PABC management setting is serial mass size measurement after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Sonographic criteria of PABC do not significantly differ from non-PABC (Figure 1). The most common finding in ultrasound is mass. Most of these masses tend to have large cystic parts that can be induced due to their invasive nature and central necrosis (17, 18). So, it is important to note that cystic-solid (complex) masses, which is discovered during pregnancy and lactation, should be biopsied and should not be abandoned to the abscess or galactocele unless clinically apparent. Sonographic criteria are helpful in the determination of malignant and benign masses (Figure 1). According to the system of BI-RADS (breast imaging and data reporting system), ultrasound specimens including spiculated margin, irregular shape, and non-parallel orientation are potent malignant suggestions, while the elliptical shape and well-defined margins are in favor of benign tumors. In pregnancy and lactation, due to physiological changes in breast tissue, we may not have typical ultrasonographic views of malignancy. In a study, 58% of masses with malignant pathology demonstrated parallel orientation, as we know this is a sign of benign masses (19). Posterior enhancement, which is commonly seen in benign lesions, has been reported in 63% of PABC cases in a study (19). In various papers, biopsy was recommend for every solid mass, which was discovered in ultrasound during pregnancy. One of the other ultrasound application for PABC, according to NCCN guidelines (2017), is the evaluation of liver metastasis in patients with PABC, who are diagnosed with axillary lymph node involvement or have tumors in the T3 and higher (above 5 cm).

A 37-year-old breastfeeding woman 9 months postpartum presented with a growing tender mass in the upper outer area of right breast: A, ultrasound images showed a 38*19 mm spiculated, heterogeneous mass with an adjacent satellite lesion measured12*15 mm in the upper outer portion of the right breast midzone; B, on ultrasound examination of right axilla, thick cortex axillary lymph nodes with squeezed hilum are seen; C, after core needle biopsy, invasive ductal carcinoma with lymph node metastasis was found in the submitted specimens.

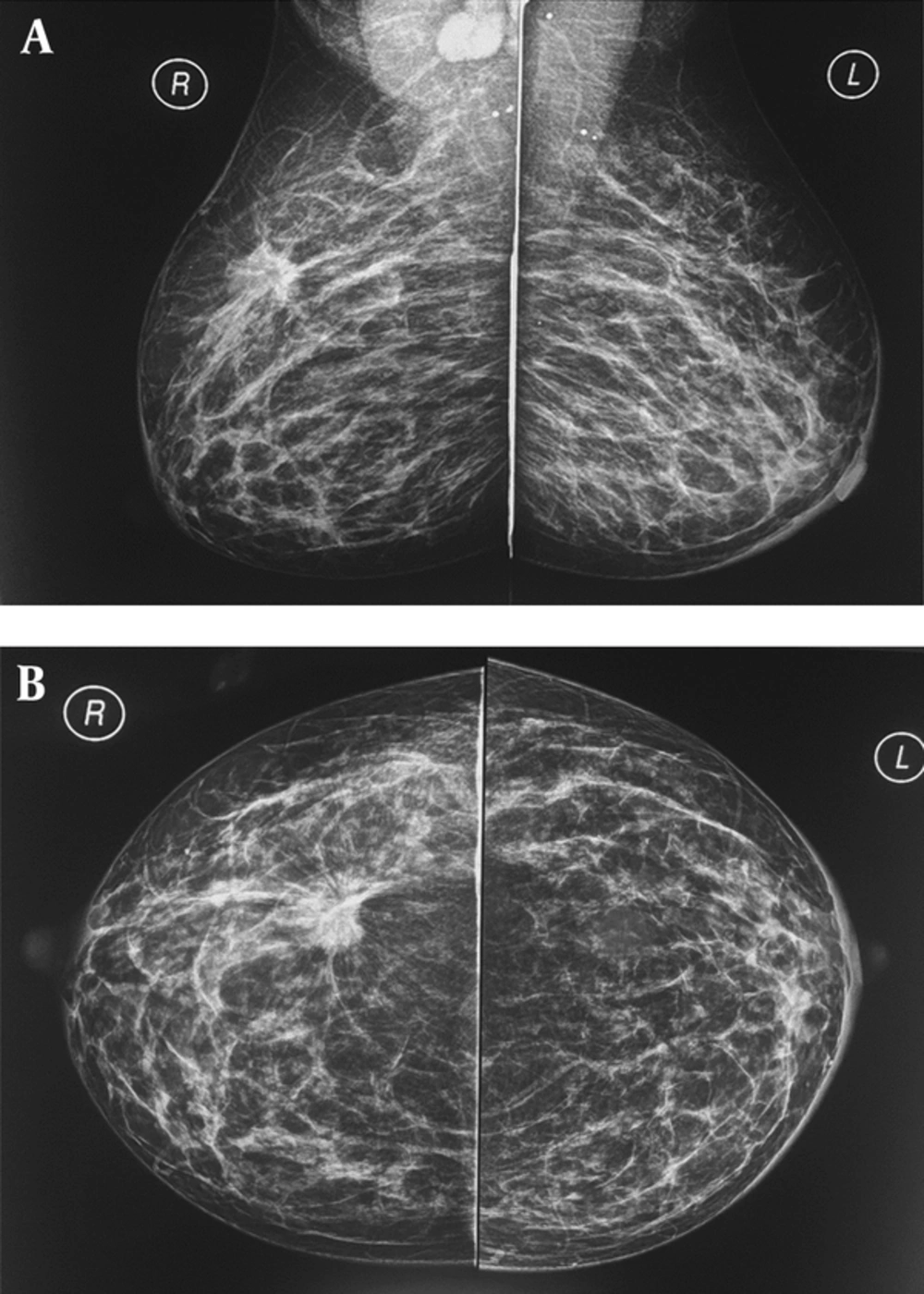

A and B, A 37-year-old breastfeeding woman 9 months postpartum presented with a growing tender mass in the upper outer area of right breast, on the obtained CC and MLO view mammographic images in right upper outer quadrant there is a spiculated irregular shaped mass causing tissue distortion associated with right axillary lymphadenopathy, metastasis to left axillary lymph nodes causing left areolar thickening; final histologic report revealed invasive ductal carcinoma.

3.2.2. Mammography

Mammography during pregnancy and lactation is a very safe method, and the use of abdominal shielding simultaneously can reduce the amount of radiation by up to 50% (20). Bilateral full-field digital mammography radiation dose is less than 3 milli-grays (21). The scattered dose of radiation to the uterus is very low (approximately 0.03 mg). It is necessary to recall that teratogenic effects of radiation on the fetus at doses lower than 50 milli-gray are not yet reported (22). Although mammograms are relatively harmless in the pregnancy and lactation phase, it is only recommended in cases with suspicious findings on clinical examination or ultrasonography (Figure 2) or cases with a known malignancy (a patient had undergone biopsy). Mammographic sensitivity for PABC detection is in a range of 78% to 90% in the literature (4, 10, 22), which can be due to hormonal changes and increased breast density. However, mammography accurately detects suspicious microcalcifications (not seen in ultrasound) and multifocal and multi-centered lesions.

During breastfeeding before performing mammography, it is better to pump breasts. In breastfeeding and pregnancy, the routine screening mammogram is not recommended. In women older than 40 years, screening mammography is best avoided until 3 months after lactation, till the breast parenchyma returns to its original state (23).

In high-risk women such as cases with BRCA mutations, routine screening begins at age of 25 with MRI and continues with mammography at age of 30. In women with a high risk of breast cancer during pregnancy, screening mammography is postponed to 3 months after delivery (24).

The most common mammographic findings of PABC include a mass with no accompanying findings, calcification, increased skin thickening with increasing parenchymal density, respectively (4, 10, 22), which are similar to non-PABC. It should be noted that although the suspected mass may not be seen on the obtained mammographic views due to the high density of the breasts, the images should be carefully evaluated for other signs, such as axillary lymphadenopathy, asymmetric densities, or microcalcifications.

3.2.3. MRI

MRI contrast agents during lactation and pregnancy are categorized as group C according to the FDA (food and drug administration) classification. Therefore, contrast agents are not recommended during pregnancy, although some guidelines such as the European Society of Urogenital Radiology find this harmless since the proven teratogenic effects have not been reported in humans (25). Gadolinium crosses the placenta and some of it is contained in the amniotic fluid by excreting from fetal kidneys; hence, the toxic effects of free gadolinium cannot be ruled out on the fetus (26) routinely intravenous gadolinium should be avoided during pregnancy and used only if it is judged absolutely essential. Gadolinium may cause a high blood level in the fetus; this condition in adults causes the nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) syndrome. The probability of this condition in the fetus and infants under the age of 1 is low due to underdeveloped kidney function. However, in some academic sources, the use of gadobenate demeglumine and gadoterate megluminine (dotareme) are recommended because it has not been reported any case of NSF by injecting these two drugs until now (8). The national radiological protection board in the United Kingdom stipulates in its principles for the protection of patients and volunteers during MRI that it “might be prudent to exclude pregnant woman during the first 3 months of pregnancy,” whereas the latest American College of Radiology guidelines for safe MRI practices does not differentiate among the pregnancy trimesters, and states that all pregnant patients could undergo MRI as long as the benefits outweigh the risks. Because of theoretical concerns, we advocate a cautious approach to using obstetrical MRI in the first trimester and in this trimester, MRI should be restricted to maternal indications (27). There are no published studies of the long-term effects in children and significant acoustic impairment resulting from exposure to prenatal MRI even with at magnetic field strengths of 3 T or more (27). In lactating patients with newly diagnosed cancers, MRI with contrast is safe and helps to determine the spread of the disease. Breastfeeding before obtaining MRI sequences is recommended. It should be noted that the similarity of lactation changes with suspicious findings can reduce the sensitivity of MRI (28). Gadolinium is secreted very little in milk; however, according to the American college of radiology guidelines, it is not necessary to stop lactation after the contrast injection (26). By the way, the patient can be depending on his desire, stop breastfeeding for up to 24 hours until Gadolinium is completely removed from milk. For screening of high-risk patient in lactating phase, MRI has limitations because of some controversies in the interpretation. Unfortunately, little studies about MRI findings of PABC have been done. In a study of 7 patients in the lactation phase with the final histological report of PABC, 5 had a clear appearance of their cancer in T2 without contrast that could be due to increasing water content of fibroglandular tissue causing increase the intensity of T2 (21). In surveys, MRI images of PABC have been reported similar to those of non-PABC, and the most common findings are masses with homogeneous, heterogeneous, or rim enhancement as well as nonmass lesions with segmental enhancement or one-sided diffuse enhancement. Lactation agents, unlike non-PABC, have a rapid parenchymal background enhancement with the type B kinetic curve (early plateau enhancement), which may be misleading to malignancy, although malignancies usually show more rapid and severe enhancement. MRI is important in detecting the spread of disease (21, 28).

3.3.4. Staging of PABC

In the process of staging, modalities with radiation are reasonable if they are effective in the management of the disease, otherwise it is best to avoid them. Ionizing radiation can damage the fetus's DNA directly or through free radicals. Radiation complications include mental retardation and organ malformation that are more common in conventional radiology and occur at higher doses of 0.2 Gy (23). The most frequent encountered organs involved in metastasis are the liver, lung, and skeletal system, routinely staging with chest x-ray, liver ultrasound, bone scan, or bone MRI without contrast. A chest x-ray with fetus shielding can be done safely in pregnancy. The preferred method of diagnosis of metastatic according to NCCN 2016 is non-contrast MRI. A bone scan is applicable only in cases, where the patient has undetectable MRI findings. In the evaluation of diagnostic methods, sentinel lymph node biopsy is not recommended for less than 30 weeks pregnancy and it is contraindicated to perform with iso-sulfan-blue and methylene blue. There are few case studies that explain the association between the use of tracer radioactive materials and fetus anomalies. PET scan is not indicated in staging (8). The risk of metastasis is approximately 0.9% when cancer diagnosed with 1 month delay and this risk is 2.6% and 5.1% in the delay of 3 months and 6 months, respectively, if considering the doubling time of the mass 130 days (24). On the other hand, if the doubling time of the mass is 65 days, the estimated metastatic risk of these numbers increases by 1.8%, 5.2%, and 10.2% for 1, 3, and 5 months, respectively (29). Finally, in young patients with PABC in pregnancy, 48% of cases have positive familial history, 2% to 29% are with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations; therefore, in PABC cases, genetic counseling is recommended (30, 31).

4. Imaging-Guided Interventions

When a suspicious lesion is discovered in ultrasound, the basic diagnostic tool is US-guided core needle (14 G) biopsy. For lesions detected only in mammography, the stereotactic biopsy could be performed and it is harmless during pregnancy and lactation. MRI guided biopsy can also be done in breastfeeding. Before starting the procedure, the patient should ensure that local anesthetic with subcutaneous lidocaine during pregnancy and lactation does not cause any problem for the fetus. It should be noted that due to the increased vascularity of the breast and dilation of the milk ducts in this phase, the risk of bleeding and infections is increased (28). One of the rare complications of biopsy is milk fistula.

5. Conclusions

Nowadays, most women delay their pregnancy until middle age and the prevalence of PABC is increasing. Ultrasound is a selective approach to examining any palpable abnormalities in pregnant and lactating mothers. Subsequently, the detection of any solid or complex mass needs further investigation with biopsy. Further evaluation with bilateral mammography should be performed in patients with suspicious findings in ultrasound. The mammogram can detect malignant microcalcifications and some hidden abnormalities. It should be noted that even if no abnormality discovered in sonogram or mammogram biopsy should be performed from the region of persistent palpable nodularity or thickening. Delay in detecting PABC has significant clinical effects on patient's survival rate.

.jpg)