1. Background

Cancer is one of the major health challenges in many countries of the world (1), which has been having an increasing rate in Iran, too. According to the published statistics, annually, 80000 new cases of cancer and 30000 cancer-related deaths are reported in Iran (2). These figures reflect the community’s growing need to providing special care for patients with cancer (3) and necessitate palliative care provision (4). Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life for the patient and his or her family confronting the problems caused by life-limiting illnesses such as cancer, by preventing the patient from suffering and relieving it, as well as initial identification, pain treatment and solving other physical, mental, spiritual, and social problems of the patients and their families (5). Providing this kind of care is done in a variety of settings and in the form of the two general approaches of hospital based and non-hospital-based (6).

Since the end of the last century, there has been a strong tendency to use home care instead of hospital care and the demand for informal care, which is defined as the unpaid care provided to a patient with cancer (7). The purpose of applying this change is to replace inpatient care with outpatient care as well as providing part of the care that the patient may need by the family (8, 9). In this situation, palliative care is not being an exception (9, 10).

Home care is one of the most desirable palliative care models empowering the patient and his or her family in providing the necessary care. Due to the prolonging of the illness and, consequently, the need for patient care process in the hospital, the families tend to continue care provision at home (11). The findings of a study show that more than 70% of the participants in the research tended to be given the end-of-life care at home (12). On the other hand, based on the upstream documents, providing home care and performing it at its best is one of the goals of the Ministry of Health in Iran (13) and is considered one of the main and essential needs of the health system of the country, regarding its economic and social benefits (4). Since the designing and implementation of a caring model necessitates the assessment of the structure and functions of the health care system in that country, as well as the opinions and views of the providers of that service (14), the first step in implementing the home care model will be to study the possibility of carrying it out or its feasibility (15).

There are several factors involved in feasibility, including the accordance of the care-treatment program with the health system (16), the overall agreement on the implementation of the program by the policy makers (13, 14), socio-cultural accordance (16), the tendency of service users, and management factors such as the existence of required facilities, equipment and manpower (14, 17).

Among the above-mentioned factors involved in feasibility, human resources are considered an important one, and nurses represent most of the manpower providing home care for patients with cancer. On the other hand, nurses are the centerpiece of the system providing this type of service (18). Furthermore, considering the fact that human factors and their outlook can lead to the improvement of the security and quality of home-based services (19), it seems necessary to be aware of the viewpoints of the key stakeholders and actors regarding the applicability of the home care plan, and to provide quality care (14). So, the research question is how far it is possible to implement home palliative care. In this regard, the nurses’ viewpoints regarding the feasibility of the implementation of the home care plan as well as the barriers to the establishment of this type of care as a part of feasibility have been investigated from different aspects.

2. Methods

In this descriptive study, 196 nurses, who had been selected from all over Iran in a period of 4 months (from September to December, 2017), filled out “a Global Home Health Nursing Care Assessment” questionnaire. The purpose of this type of sampling was to attempt to distribute the questionnaire in different parts of the country, among nurses working in different wards, and as a result, to examine nursing care provision at home all over the country. The questionnaires were distributed among nurses, who had at least 6 months of work experience in nursing and work experience in hospitals affiliated to universities of medical sciences. The list of cities, where nurses filled out the questionnaire, is included in the supplementary file Appendix 1.

The research tool was a “Global Home Health Nursing Care Assessment”. This questionnaire had 3 general sections completed on the basis of research objectives.

The first part consisted of the demographic information of nurses, which was collected through analyzing 11 variables, including age, sex, questions about providing home care at the moment, job status in terms of working hours, the city, where they worked, the type of the area, where the service was provided in terms of population, educational degrees, where their degrees had been issued, nursing job experience, taking retraining courses in different fields, and the language used in care provision process.

The second part of the questionnaire (with 36 items in the form of yes/no questions, and 4-point Likert scale) evaluated the rate of social acceptability of home care provision with 1 item, the extent to which each assigned task is performed through 22 items and how they were done in the form of team work through 13 phrases.

Using the third part of the questionnaire (with 32 items in the form of yes/no questions, and 4-point Likert scale), the level of the nurses’ satisfaction with access to facilities or the variety in doing activities (the facilitators of home care provision), the existing barriers to the process of establishing the home care plan, and the main barriers to accessing educational opportunities were studied.

Due to the lack of an appropriate scale in the country for assessing the possibility of home care provision from the nurses’ perspective on providing home palliative care, the translation and psychometric evaluation of “Global Home Health Nursing Care Assessment questionnaire” was carried out. For this purpose, the process of scale translation was performed after correspondence with the original designers and asking for their permission based on the 8-step model presented by Wild et al. (20). Then, its qualitative content validity was evaluated and approved by 10 nursing specialists familiar with home care provision process. The face validity was also measured based on the views of 10 nurses qualified to take the survey. The stability reliability was calculated by calculating ICC, using One-Way Random Effects Model on 25 nurses qualified to take the survey. The single Measure ICC was measured 0.86 with a confidence level of 0.95 among Iranian nurses. The nurses were handed a Global Home Health Nursing Care Assessment questionnaire to fill out. The approximate time for completing each questionnaire was 20 minutes and the nurses filled it out during their break or at home not later than two work shifts. While handing in the questionnaire, the nurses were given a gift as a token of researchers’ gratitude and a souvenir.

The data were analyzed, using descriptive statistics of central and dispersion indicators, frequency distribution tables, and the statistical charts related to SPSS software version 20.

This research is a part of a project approved by Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.SBMU.PHNM.1396.834. In order to observe the ethical principles and to maintain the right of participants, the research has been conducted according to the code of ethics. In order to collect data, a written informed consent was obtained from participants. They were also assured of the confidentiality of information and the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any stage of the research.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

Most of the samples in this study were women (69.7%). The mean age of the participants was 30.71 ± 7.03. Half of the nurses (50.5%) were employed at home. However, only 25.5% of nurses had taken home care training courses. Other demographic characteristics of nurses, including employment status, level of education, and work experience are presented in Table 1.

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Employment status | ||

| Full-time | 64 | 32.65 |

| Part-time | 78 | 39.80 |

| Daily paid | 30 | 15.31 |

| Registered | 12 | 6.12 |

| Other | 12 | 6.12 |

| Total | 196 | 100 |

| Level of education | ||

| BSc in nursing | 127 | 64.80 |

| MSc in nursing | 18 | 9.18 |

| MSc in related fields | 46 | 23.47 |

| PhD in Nursing | 5 | 2.55 |

| Total | 196 | 100 |

| Working experience, y | ||

| ≥ 1 | 35 | 17.87 |

| 2 - 5 | 124 | 63.26 |

| 6 - 10 | 11 | 5.61 |

| 11 - 5 | 6 | 3.06 |

| 16 - 20 | 17 | 8.67 |

| > 20 | 3 | 1.53 |

| Total | 196 | 100 |

3.2. Nurses’ Views on the Possibility of Palliative Care at Home

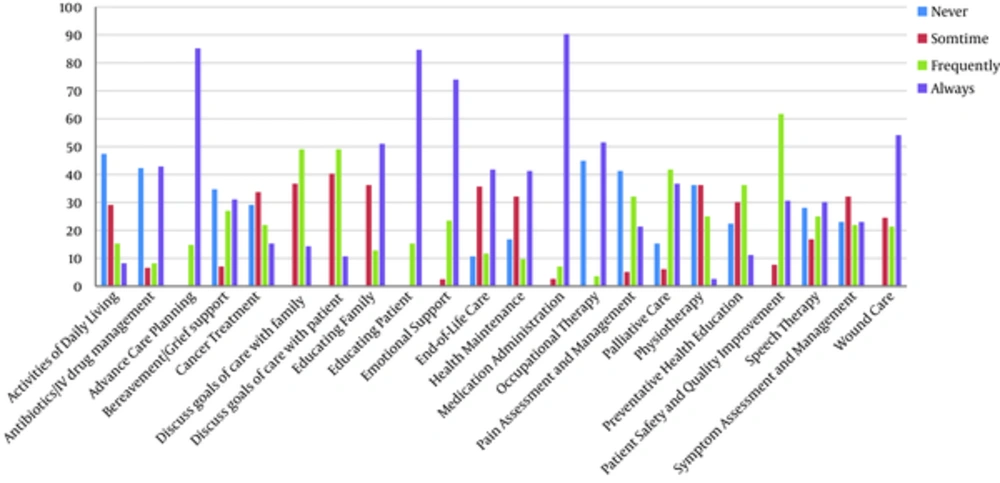

In this study, 47.4% of the participants believed that home care provision is socially acceptable. In addition, regarding the next part of the questionnaire on prescribing medications, in the nurses’ opinion, planning for providing advanced care, wound care, and patient education were the most important measures to be taken in providing home care for patients with cancer, while some services, including helping patients do their daily activities, such as maintaining individual health, and evaluating and managing symptoms (such as nausea, vomiting, fatigue, diarrhea, and microsites) were among the services less frequently provided by nurses. Figure 1 shows the amount of nursing duties performed in providing home care.

Most nurses (62.2%) preferred to have some home health aide by their side while providing home care. Considering the specialized level of care, cooperation with the following forces was prioritized as nurses (100%), specialist physicians (69.4%), nutritionists (36.2%), and psychologists (35.7%).

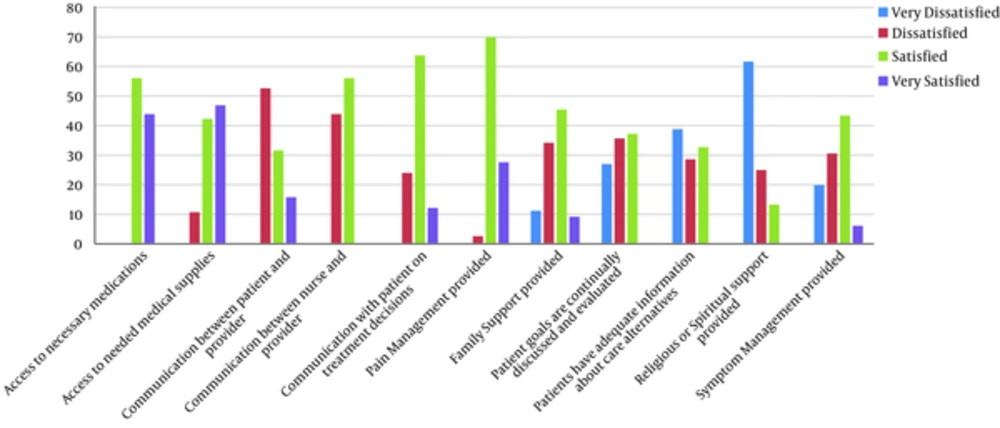

Nurses were most satisfied with the accessibility of essential drugs, medical equipment, and pain control, and mostly dissatisfied with the lack of religious or spiritual support and informing patients about their diseases.

Figure 2 shows the nurses’ satisfaction from different aspects of accessing resources and performing assigned duties.

However, there were some barriers to the implementation of proper home care. The most important barriers from the viewpoint of nurses were lack of access to end-of-life care and hospice care. Other barriers are shown in Table 2. Barriers to accessing educational opportunities were also assessed from the nurses' point of view. Financial barriers (66.3%), time barriers (61.7%), and barriers due to the lack of alternative forces while attending classes and educational conferences (56.1%) were among the reasons that limited access to the appropriate educational opportunities the most.

| Row | Barriers | Frequency | Percentage | Average | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Communication problem with patients | 105 | 53.57 | 1.41 | 0.76 |

| 2 | Communication problem with family | 63 | 32.14 | 0.92 | 0.84 |

| 3 | Communication problems among team members | 37 | 18.88 | 0.67 | 0.77 |

| 4 | Cultural beliefs affecting the care procedure | 86 | 43.88 | 1.11 | 0.86 |

| 5 | Lack of access to end-of-life care and hospice care | 153 | 78.06 | 2.03 | 1 |

| 6 | Lack of access to opioid drugs for pain management | 152 | 77.55 | 2.20 | 1.07 |

| 7 | Lack of community awareness on the services provided | 63 | 32.14 | 0.92 | 0.84 |

| 8 | Lack of funding | 143 | 72.96 | 2.13 | 0.81 |

| 9 | Lack of Guidelines and instructions | 86 | 43.88 | 1.11 | 0.86 |

| 10 | Lack of employee training | 156 | 79.59 | 2.08 | 0.79 |

| 11 | Language barriers | 86 | 43.88 | 1.45 | 0.72 |

| 12 | Personnel shortage | 43 | 21.94 | 1.05 | 0.69 |

| 13 | Religious and spiritual beliefs affecting care | 47 | 23.98 | 0.98 | 0.69 |

| 14 | Time limitations | 90 | 45.92 | 1.40 | 0.83 |

4. Discussion

In the recent years, significant changes have happened in the palliative care system in the form of transforming hospital care into home care (8, 9).

Home care is one of the most desirable models of providing palliative care (21), but considering the dominant traditional beliefs of Iranian society (22), the economic and social status of the country and the extent of access to various resources, the possibility of providing home care should be assessed. In order to implement any health care plans, the opinions of service providers should be investigated (14). Therefore, this research was conducted with the purpose of evaluating the feasibility of home care provision from the nurses’ point of view.

Despite the fact that half of the nurses participating in this research are involved in giving home care, almost one quarter of them received training in palliative care provision at home, which is not significantly different from the findings of some other conducted studies (23-25).

Care team members should receive professional training. In fact, the lack of education is considered as one of the barriers to providing palliative care services (21, 26). In Iran, even several years after offering Master’s degree programs in community health nursing, there are still no nurses at this level of care to provide home care, which is a result of the lack of defined positions at the community level and the lack of job descriptions for them (27).

Social and cultural appropriateness, and as a result, the social acceptability regarding the feasibility of home care provision are among the important factors to be considered (16). Nearly half of the nurses in the present study believed that providing home care for patients with cancer is socially acceptable.

Once there exists social acceptability and favorable conditions for providing home care or creating necessary infrastructures for offering these services, it should be determined which care services are qualified to be provided at home from the nurses’ point of view, considering their scientific and practical characteristics and what they do as the most important providers of home care services.

According to the nurses participating in the current research, the most important nursing duty is prescribing medicines. In the area of palliative care, drugs are also prescribed by some members of the palliative care team other than physicians. The purpose of developing non-medical prescribing (NMP) in this area is to improve patient care, patient safety, and the better use of professional and teamwork skills (28). However, giving drugs in Iran is considered as one of the nursing practices done only based on doctors’ prescriptions. In Iran, the biomedical paradigm unconsciously leads nursing students to being good doctors’ assistants, and as a result, a tendency to carry out associate activities such as prescribing medicines as the main task (13, 29). Wound management was also one of the care services that nurses considered necessary to be provided at home. More than one-third of the patients needed wound management at home, a quarter of those wounds were pressure ulcers (30). Chrisman’s studies showed that examining skin integrity and preventing the infection of skin wounds are among the most important activities that nurses should do while providing care, especially at the end of life (31).

Educating patients and their families was another important item highlighted by nurses. However, the results of some studies indicate that this is sometimes neglected due to various reasons such as the multiplicity in nursing duties or the shortage of nursing staff (32, 33).

On the other hand, it is less important for nurses to help patients maintain their personal hygiene. In their opinion, helping patients maintain their personal hygiene should be addressed by home health aides.

Symptom assessment and management (excluding pain symptoms) has not been considered very important from the perspective of nurses in this study, either, while in countries pioneer in providing palliative care such as Canada, more than 50% of nurses use available standard tools for this purpose (34). In providing palliative care in community-based settings, especially at home, symptom management is the most frequent activity undertaken by nurses (35). However, ignoring the importance of symptom management in this research is justifiable considering the type of nursing education because nurses regard the diagnosis of these symptoms as physicians’ duty and delay taking actions until then (32, 33, 36, 37).

Regarding the type of care provided at home for a patient with cancer, they believe that cooperating with other nurses, nutritionists, psychologists, and especially specialist doctors such as oncologists, is necessary while providing specialized care according to patient’s conditions. Doing teamwork is important for nurses, given the teamwork nature of care provision for patients with cancer on one hand, and none of the disciplines’ being authorized to carry out specialized activities without a doctor's order in Iran, making the doctor responsible for continuing the treatment of his/her patients on the other hand (13).

In this research, with regard to the availability of resources and doing their assigned duties, nurses were mostly satisfied with accessing necessary drugs for pain control. Iran has the proper raw materials technology to manufacture opioid painkillers. Some large pharmaceutical companies have been manufacturing drugs such as methadone, codeine, oral oxycodone, and injectable morphine. The prices of these drugs are really low as well. But, what is challenging is that according to the statistics provided by the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), Iran ranked low in using such medicines, the 115th in the world, the 25th in Asia, and the 15th in the region due to the negative attitude of doctors, nurses, patients, and their families towards opioid medicines and sometimes a broad resistance to them (22).

The nurses participating in this study were also satisfied with the availability of medical equipment. Regarding equipment, Iran has good equipment and facilities and has implemented a variety of therapeutic and diagnostic procedures for patients (27).

Nurses were less satisfied with providing religious-spiritual care and informing patients about different treatment procedures: Spirituality is considered as one of the important components of palliative care, which improves the quality of life for patients and their families (38). The findings of Hatamipour et al. regarding the spiritual needs of patients with cancer in Iran shows that these patients have multiple spiritual needs that appear in the form of connection, seeking peace, meaning and purpose, and transcendence. Nurses can address these needs well considering the dominant religious backgrounds (39). Nurses’ insufficient knowledge of how to provide spiritual care, the lack of time, the shortage of skilled manpower, the lack of required confidence and the fear of breaking down ethical, and professional and social boundaries due to improper provision of this kind of care are among the reasons for ignoring this matter (38, 40).

According to the nurses, the extent to which the patients are informed about different ways of treatment was not satisfying. A study conducted by Larizadeh et al. showed that 64.7% of patients with cancer were not aware of their disease and only 38.7% of them were involved in determining the treatment plan (41). However, a study suggests that 97% of doctors in western countries tend to tell the truth to their patients about their disease (42).

This contradiction can be associated with the culture of Iranian patients. In contrast to western cultures that emphasize “truth telling”, in some cultures (such as Middle-Eastern cultures, especially Iran), it is not unusual to hide a cancer diagnosis from the patient. In some cultures, talking about death and serious illnesses is an act of disrespect and non-polite behavior. Some argue that informing the patient may lead to his/her hopelessness, and in some cultures, it is believed that talking about death and terminal illnesses makes these incidents come true (37).

The nurses’ opinion on the barriers to the implementation of home care is another important step towards making this program possible. From the nurses’ point of view, the lack of access to end-of-life care and hospice care, and, then, to educational opportunities were among the most important barriers to proper home care provision.

Providing end-of-life and hospice care, especially in the situations, where cancer and consequent death rates are high necessitating supportive specialized care, is considered as one of the main requirements of the health system. Generally, there are few care centers such as hospices in Iran. As a result, patients receiving home care have to receive necessary services in hospitals, following the disease’s getting worse (22).

According to the nurses, the lack of access to educational opportunities has been considered a major barrier to providing palliative care at home, for which various reasons have been mentioned such as lack of sufficient time, financial problems, and the shortage of available substitute manpower in order to attend training courses. Some studies in Iran have shown that nurses are not skillful and efficient enough yet and need more appropriate training to understand this concept and, consequently, to provide care (21, 22, 43).

The research population only consists of nurses working in the oncology departments of educational hospitals in Iran. Therefore, one of the limitations of this research is the small number of nurses involved. Among other limitations, the novelty of home care provision for patients with cancer and, as a result, limited opinions of nurses due to little experience in this area can be mentioned.

4.1. Conclusions

Home care is one of the most desirable palliative care models, considered as one of the important and essential needs of the health system of Iran. Since the opinions of care providers are a major factor, on which the implementation of a care treatment program depends, it is necessary to be aware of their views on the feasibility of a home care program and providing a quality care. The results show that based on the nurses’ opinions about providing home care for patients with cancer, they have social acceptability and relative satisfaction, for example regarding their access to medications, equipment, and pain management. However, while studying the barriers, the lack of educational opportunities and a chance to provide end-of-life care have been mentioned. With proper planning, using the available potential as well as applying proper changes in nursing undergraduate curriculum, existing barriers can be overcome and home care for patients with cancer can be developed. Finally, according to people’s age groups, the Iranian society is ageing and, as a result, the prevalence of various chronic diseases is anticipated. Therefore, the results of this study are applicable for all patients with chronic diseases, especially different types of cancer and also for the elderly care both in hospital-based care and community-based settings.