1. Context

Esophageal cancer, including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma (AC), is considered as a malignant disease with fatal consequences worldwide (1, 2). Among cancers, it is the sixth most common cause of mortality in the world, with an estimated 509 000 deaths in 2018 (3).

Cancer of the esophageal has a very poor survival, even in developed countries. Based on the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) data, the 5-year survival rate increased from 5% in 1975 to 19% in 2005 (4). In addition, it is below 15% in developing countries (5, 6).

According to clinical guidelines, there are different treatments for esophageal cancer, including esophagectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection, ablation, chemoradiotherapy, and chemotherapy (7-9). Each treatment has its own cost and benefit; for example, a study shows that the cost for esophagectomy and ablation was $515 65 and $174 19, respectively, while health-related quality of life for esophagectomy and ablation was 0.92 and 0.93, respectively (10). The previous evidence showed that there are many limitations in the comparison of esophageal cancer treatment, as each treatment has advantage and disadvantage; in addition, there is no predominant strategy for treatment of this cancer. Also, most studies only examined the clinical outcomes of the treatment modalities, and the number of studies that compared clinical outcomes and treatment costs was very rare (11-13).

Under conditions of uncertainty and limited resources, economic evaluation is a useful tool in comparing mutually exclusive strategies and in calculating the cost and effectiveness of different strategies (14, 15). A full economic evaluation can provide experts with an analytical tool to compare health benefit and cost a therapeutic approach. Such analyses are utilized in many countries because these methods help them determine how to achieve the greatest health benefit with a limited budget, a challenge that every health system faces (16, 17).

2. Objectives

The main objective of our study was to critically appraise and summarize current evidence on the economic evaluation of esophageal cancer treatments. Furthermore, we aimed at; first, providing a summary of the best evidence to support policymaker, especially in countries located on the esophageal cancer belt; second, comparing the treatment methods of esophageal cancer to propose a cost-effective treatment.

3. Data Sources

3.1. Publication Search

We conducted systematic searches in Medline through PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases in July 2018. The search was limited to English language publications and studies published before July 17, 2018. To find all the related articles, we performed comprehensive search strategies to reduce the risk of losing any articles. The search strategy contained two different parts, including esophageal cancer and economic evaluation. For example, in Scopus, we applied the following search strategy: “TITLE-ABS-KEY (“esophageal cancer*” OR “esophageal tumor*” OR “esophagus cancer*” OR “esophageal carcinoma” OR “Esophageal Neoplasm*” OR “Esophagus Neoplasm*” OR “Esophagus tumor*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“cost-effectiveness” OR “cost-utility” OR “cost-benefit” OR “cost-minimization” OR “economic evaluation”)”.

Our PICOD included population (P) (people of esophageal cancer), interventions (I) and comparison (esophagectomy, endoscopic mucosal resection, ablation, chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy), outcomes (O) (cost-effectiveness including, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios [ICERs]), and design (D) (full economic evaluation).

3.2. Inclusion Criteria

The articles studying the economic evaluation of esophageal cancer treatment were included. We included all economic evaluation studies, including, cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, cost-benefit, and cost-minimization studies. In addition, we included studies that compared any treatment of esophageal cancer. The exclusion criteria were as follow: (1) economic evaluation studying that assessed Barret esophagus, only high-grade dysplasia, screening, and cancer diagnostic test; (2) review articles, editorials, and protocols; and (3) studies that compared only cost and economic burden.

3.3. Study Selection

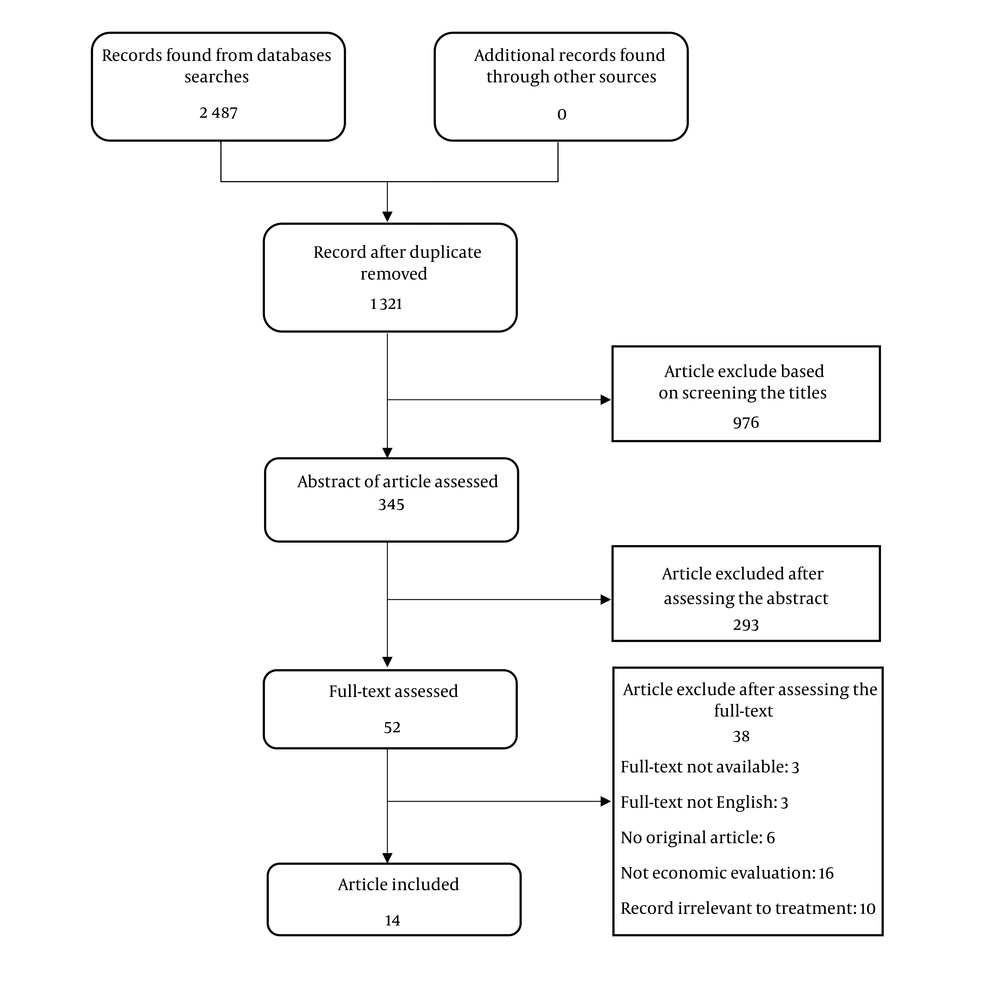

Study selection was applied independently by two reviewers in 3 steps. First, the records were entered in the data management software and duplicates were removed. The title of the remaining articles was screened and excluded the articles that were unrelated to our review. Second, abstracts were assessed based on the inclusion criteria and we omitted the papers that were unrelated to our study. If there was no agreement between the two reviewers for omitting an article, the third author would review the article. Finally, full-text of the remaining articles were obtained and assessed for final inclusion in our systematic review.

Quality assessment of studies and data extraction were performed by two authors. Drummond’s checklist was used for quality assessment. The checklist included 10 questions (14, 18).

3.4. Data Extraction

Data were extracted for some variables from each paper. The variables were author’s name, published year, country, interventions, comparator, economic perspective, time horizon, discounting rate, cost, effect, type of modeling, incremental cost effectiveness ratio (ICER), sources for cost and effect, threshold and cancer subtype.

We divided the included studies based on interventions as follow; (a) the studies were compared esophagectomy versus endoscopy treatment (ET), (b) the studies assessed esophagectomy compared with chemotherapy regimens, (c) studies that compared chemotherapy regimens, and (d) studies compared palliative care.

Our main outcome measure was the cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY), although other outcome measures such as cost per life year gained and cost per survival rate were also considered.

4. Results

4.1. Description of the Included Studies

Figure 1 displayed the process of studies selection for systematic review diagram. Overall, the search yielded 2 487 hits of 5 databases. Once 1 321 records remained after excluding duplicates. After screenings and assessments, the full-text of 52 articles were assessed. The full-text of 3 articles was not available, 3 full-texts were not published in the English language, 6 records were not original paper, 16 articles were not an economic evaluation, and 10 articles were irrelevant to esophageal treatment. Finally, only 14 eligible studies were included in the review.

The results of the quality assessment according to Drummond’s 10 item checklist shows that out of the 14 economic evaluation, 12 studies scored = > 8 points and 2 studies scored = 6 point. The quality assessment result is available upon request.

The general description of the eligible studies is listed in Table 1. Out of the 14 articles, 8 were published before 2010. The others were published in 2012 (3), 2013 (3), 2016 (4), and 2018 (4). Most of the studies were conducted in the United States of America (USA) (2) and the United Kingdom (UK) (2). Other studies were conducted in Australia (one), Taiwan (3), the Netherlands (3), Sweden (3), Greece (3), and Canada (3). The majority of the evaluations (8) followed a healthcare system perspective. Other studies were conducted from a payer’s perspective. Regarding the time horizon, time frame 1 to 5 years was utilized in 6 studies, lifetime was considered in 5 studies. Two studies applied timeframe under 1 year.

| Authors (Year), Country (Ref.) | Interventions | Economic Perspective (Time Horizon) | Model (Discount Rate) | Source for Effects and Cost Data | Cancer Subtype | Type of Evaluation (Threshold for Cost Effectiveness) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Esophagectomy vs. Endoscopy Treatment | ||||||

| Harewood and Wiersema (2002), USA (19) | Surgery, EUS FNA, CT FNA | Third party payer (not reported) | Decision tree (not applicable) | Effect: published literature cost: AMACPT, medicare fee schedule | Not specified | Cost minimization (not applicable) |

| Pohl et al. (2009), USA (20) | Surgery, EMR | Payer (5 years) | Decision tree (not applicable) | Effect: published literature, cost: based on DRG and AMACPT estimates | AC | CEA ($50000 per QALY gained) |

| Gordon et al. (2012), Australia (10) | Esophagectomy, EMR, downstaging, Add PET, chemoradiotherapy | Health system (5 years) | Decision tree (5%) | Effect: ACS, published literature, cost: patient-level from ACS, hospital record | AC | CEA ($50000 per QALY gained) |

| Chu et al. (2018), USA (21) | Esophagectomy, ET | Not reported (life time) | Markov (3%) | Effect: SEER data, published literature, cost: published literature | AC | CEA ($100000 per QALY gained) |

| B: Esophagectomy vs. Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Lin et al. (2016), Taiwan (22) | Esophagectomy, NCCRT | Payer (3 years) | Decision tree (not applicable) | Effect: Taiwan cancer registry, cost: national health insurance | SCC | CEA (US$50000-150000 per life year) |

| Fong Soe Khioe et al. (2018), UK (23) | Adjuvant statin + surgery, no-statin therapy | Health system (life time) | Markov (3.5%) | Effect: cohort of CPRD and study itself, cost: british national formulary and NHS data | AC | CUA (£20000 per QALY gained) |

| C: Chemotherapy Regimens | ||||||

| Webb et al. (1997), UK (24) | ECF, FAMTX | Health system (1 year) | Not modeling (not applicable) | Effect: primary data from the study itself, cost: hospital-based cost assessment | AC | CEA (not applicable) |

| Janmaat et al. (2016), Netherland (25) | CCF, CF | Health system (10.8 month) | Linear model (not applicable) | Effect: study of Lorenzen et al. cost: obtained from the dutch manual | SCC | CEA (€40000 per QALY gained) |

| D: Palliative Treatments | ||||||

| Shenfine et al. (2005), UK (26) | SEMS, Non-SEMS | Not reported (life time) | Descriptive costing study (not applicable) | Effect: primary data from the study itself cost: Micro costing model | SCC and ACC | CEA (£20,000 to 120,000 per QALY gained) |

| Wenger et al. (2005), Sweden (27) | SEMS, brachytherapy | Health system (Life time) | Not modeling (not applicable) | Effect: primary data from the study itself cost: sahlgren’s university hospital, goteborg | SCC and AC | CEA (not applicable) |

| Xinopoulos et al. 2005), Greece (28) | Stenting, laser palliation | Health system (life time) | descriptive costing study (not applicable) | Effect: primary data from the study itself, cost: micro costing model | SCC and AC | CEA (not applicable) |

| Da Silveira and Artifon (2008), USA (29) | Laser, brachytherapy, SES | Third party payer (9 month) | Markov (not applicable) | Effect: systematic literature review, cost: DRG and Medicare data | Not specified | CEA (0 to $15000) |

| McNamee and Seymour (2008), UK (13) | Plastic stent, brachytherapy, thermal ablation | Health system (1 year) | Not modeling (not applicable) | Effect: primary data from the study itself, cost: from case records by research nurses | Not specified | CEA (£10,000 to 50,000 per QALY gained) |

| Other Interventions | ||||||

| Lee et al. (2013), Canada (30) | Minimally invasive open, esophagectomy | Health system (1 year) | Decision tree (not applicable) | Effect: systematic literature review, Biere et al. study cost: mcGill university health centre, medical record | Not specified | CEA ( $0 to 100,000 per QALY in sensitivity analysis) |

Abbreviations: AC, adenoma carcinoma; ACS, Australian Cancer Study; AMACPT, American Medical Association Current Procedural Terminology; CCF, cetuximab cisplatin fluorouracil; CEA, cost effectiveness analysis; CF, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; SEMS, self-expanding metal stents; CPRD, clinical practice research datalink; CT FNA, computed tomography with guided fine needle aspiration; CUA, cost utility analysis; DRG, disease-related group; ECF, epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ET, endoscopic therapy; EUS FNA, endoscopic ultrasound with guided fine needle aspiration; FAMTX, fluorouracil (5-FU), doxorubicin, and methotrexate; HRQOL, health related quality of life; NCCRT, neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy; QALY, quality adjusted Life year; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; SEER, surveillance epidemiology and end results; SES, self-expandable stent.

Regarding the cancer subtype of the esophagus, 5 studies focused on the AC, 2 included the SCC, only 3 assessed the SCC and AC, and 4 unspecified the cancer subtype. Nine included studies used a modeling technique as the major method, including decision tree (5), Markov model (1), and linear model (3). All studies were economic evaluation: 12 were cost-effectiveness analysis, 1 cost-utility analysis, and 1 cost minimization analysis. Only 10 studies used a threshold for analysis of cost-effectiveness.

According to the types of treatment (interventions), in 4 studies, esophagectomy were compared with ET (10, 19-21), 2 studies compared esophagectomy with chemotherapy regimens (22, 23), 2 studies contrasted chemotherapy regimens (24, 25) and 5 studies compared palliative cares (13, 26-29). Only 1 study compared minimally invasive esophagectomy versus open esophagectomy (30).

Included studies utilized different sources of cost data, national databases such as British National Health System (NHS), American Medical Association Current Procedural Terminology (AMACPT) estimates, National Health Insurance and Dutch System, or organizations such as Disease-Related Group (DRG), Medicare and Medicaid Data, or Medical Record, and Micro-Costing Models. The majority of effects data was obtained from published literature.

4.2. Main Findings of the Included Studies

Table 2 shows the main findings of economic evaluations included in the systematic review. Six of the 14 studies reported the mean cost for interventions, only 3 studies estimated the incremental cost, and both the mean and incremental cost were reported in the 5 studies.

| Authors (Year), Country (Ref.) | Mean Cost or Incremental (Δ) Cost | Effectiveness Measure or Incremental (Δ) | ICER | Sensitivity Analyses | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Esophagectomy vs. Endoscopy Treatment | |||||

| Harewood and Wiersema (2002), USA (19) | Mean cost: surgery $13992; EUS FNA $13811; CT FNA $14350 | Not applicable | Not applicable | Probabilistic | By minimizing unnecessary surgery, primarily by detecting CLN involvement, EUS FNA is the least costly staging strategy in the workup of patients with nonmetastatic esophageal cancer. Under certain circumstances, surgery is the preferred strategy |

| Pohl et al. (2009), USA (20) | Mean cost: Eso $27830; ET $17408, Δ cost Eso vs. ET: $10422 | QALY: ET 4.88; Eso 4.59, Δ QALY ER vs. Eso: 0.29 | Negative ICER, ET dominant over Eso | Probabilistic | ET is more effective and less expensive than esophagectomy |

| Gordon et al. (2012), Australia (10) | Δ cost EMR (base value: T1a 90%): 100% T1a -$256; 100%T1a +25% T1b -$357; 100%T1a +50% T1b -$458, Δ cost Eso: (base value: OM: 2% to 6%): 0% OM $225; 1% OM $166; 5% OM -$70 | Δ QALY EMR (base value: T1a 90%): 100%T1a -0.001; 100%T1a +25% T1b 0.002; 100%T1a +50% T1b 0.005, Δ QALY Eso: (base value: OM: 2% to 6%): 0% OM 0.049; 1%OM 0.036; 5% OM -0.018 | INT EMR (base value: T1a 90%):100%T1a $228; 100%T1a +25% T1b $428; 100%T1a +50% T1b $628, INT Eso: (base value: OM: 2% to 6%): 0% OM $1367; 1%OM $989; 5% OM -$523 | Probabilistic | These findings support measures that promote earlier diagnosis, such as developing risk assessment processes or endoscopic surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Incremental net monetary benefits for other strategies are relatively small in comparison to predicted gains from early detection strategies |

| Chu et al. (2018), USA (21) | Mean cost for T1a: Eso $47812; ET $12977, In T1b, Eso $46345; ET $ 11366., Δ cost for T1a and T1b, $34835 and $34979 | Life years: for T1a, Eso 6.97; ET 6.81, In T1b, Eso 5.73; ET 5.01., QALY: for T1a, Eso 4.95; ET 5.22, In T1b, Eso 4.07; ET 3.85 | $/QALY gained for Eso: 156981 in T1b | Probabilistic, deterministic | ET of T1a of EAC yields more QALYs and is more cost effective than esophagectomy for patients of all ages and comorbidity indices tested. selection of therapy for T1b EAC depends on age and comorbidities |

| B: Esophagectomy vs. Chemotherapy | |||||

| Lin et al. (2016), Taiwan (22) | Mean cost: NCCRT $ 91460; Eso $75836, Δ cost NCCRT vs. Eso: $15624 | Survival (year): NCCRT 2.2; Eso 1.8 | $/life years gained for NCCRT: 39060 | Probabilistic | When compared to esophagectomy, NCCRT is likely to improve survival and is probably more cost-effective |

| Fong Soe Khioe et al. (2018), UK (23) | Mean cost: adjuvant statin $12265; No-Statin therapy $19046 | QALY: adjuvant statin 4.93; no Statin therapy 3.25 | Negative ICER, statin therapy dominant over no-statin therapy | Probabilistic, deterministic | The cohort exposed to statins had lower costs and better QALY outcomes than the no statin cohort |

| C: Chemotherapy Regimens | |||||

| Webb et al. (1997), UK (24) | Mean cost: ECF $13760; FAMTX $13500, Δ cost ECF vs. FAMTX: $260 | Δ survival ECF vs. FAMTX: 3.2 month | $/life years gained for ECF: 975 | Not applicable | The ECF regimen results in a survival and response advantage, tolerable toxicity, better QL and cost-effectiveness compared with FAMTX chemotherapy |

| Janmaat et al. (2016), Netherland (25) | Δ cost CCF vs. CF: €26,459 | Δ QALY CCF vs. CF: 0.105, Δ life years CCF vs. CF: 0.187 | €/ QALY gained for CCF: 252203 | Probabilistic, deterministic | Addition of cetuximab to a cisplatin-5-fluorouracil first-line regimen for advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is not cost-effective when appraised according to currently accepted criteria |

| D: Palliative Treatments | |||||

| Shenfine et al. (2005), UK (26) | Mean cost: non-SEMS £4792; SEMS £4648, Δ cost non-SEMS vs. SEMS: £144 | QALY: non-SEMS 0.25; SEMS 0.18, Δ QALY Non-SEMS vs. SEMS: 0.07 | £/QALY gained for non-SEMS: 2057 | Deterministic | The treatment choice for patients with inoperable esophageal cancer should be between a SEMS or a non-stent treatment after consideration has been given to both patient and tumor characteristics and clinician and patient preferences |

| Wenger et al. (2005), Sweden (27) | Mean cost: brachytherapy €35414; SEMS €24564 | Survival (mean): brachytherapy 162 day; SEMS 158 day | Not applicable | Not applicable | Stenting is currently more cost-effective compared with fractionated 3×7Gy brachytherapy for patients with incurable cancer of the esophagus and gastro-esophageal junction |

| Xinopoulos et al. (2005), Greece (28) | Mean total cost per patient: stenting €3103; laser palliation €2947 | Improvement in quality of life: in first month, stenting 96%; laser palliation 71%, in second month, stenting 75%; laser palliation 54% | Not applicable | Not applicable | Placement of self-expanding metal stents is a safe and cost-effective treatment modality that improves the quality of life, compared with laser therapy |

| Da Silveira and Artifon (2008), USA (29) | Mean cost: SES $5410; brachytherapy $4177; laser $3068 | Dysphagia score: SES 0.97; brachytherapy 1.06; laser 0.81 | ACER: SES 5559; brachytherapy 3908; laser 3756, ICER brachytherapy vs. laser: 4400 | Probabilistic, deterministic | Conditional to the WTP and current US Medicare costs, palliation of unresectable esophageal cancers with brachytherapy provides the largest amount of NHB and is the strategy with the highest probability of CE |

| McNamee and Seymour (2008), UK (13) | Mean cost: plastic stent £4538; brachytherapy £5310; thermal ablation £6084, Δ cost: brachytherapy vs. plastic stent £772; thermal ablation vs. plastic stent £1546 | QALY: plastic stent 0.25; brachytherapy 0.27; thermal ablation 0.25, Δ QALY brachytherapy vs. plastic stent: 0.02 | £/ qALY gained for brachytherapy: 38 600 | Not applicable | brachytherapy was identified as the more cost-effective treatment in terms of the incremental cost-per-QALY ratio by both the standard health outcome values approach and methods based on process values |

| Other Interventions | |||||

| Lee et al. (2013), Canada (30) | Mean yearly cost: MIE 45892 CAN$; open esophagectomy 47533 CAN$ | Mean yearly qALY: MIE 0.623; open esophagectomy 0.601 | Negative ICER, MIE dominant over open | Probabilistic, deterministic | MIE is cost-effective compared to open esophagectomy in patients with resectable esophageal cancer |

Abbreviations: ACER, average cost effectiveness ratio; CCF, cetuximab cisplatin fluorouracil; CF, cisplatin and fluorouracil; CT FNA, computed tomography with guided fine needle aspiration; ECF, epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; Eso, esophagectomy; ET, endoscopic therapy; EUS FNA, Endoscopic ultrasound with guided fine needle aspiration; FAMTX; fluorouracil (5-FU), doxorubicin, and methotrexate; ICER, incremental cost effectiveness ratio; MIE, minimally invasive esophagectomy; NCCRT, neoadjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy; OM, operative mortality; QALY, quality adjusted life year; SEMS, self-expanding metal stents; SES, self-expandable stent.

Regarding the effectiveness measure, 6 studies applied the QALY measure, and 2 studies utilized QALY and life years gained, and 5 studies used other outcomes such as survival rate, dysphagia score, and improvement in quality of life. Eleven studies could provide ICER, 3 of which showed a negative ICER. All studies applied a sensitivity analysis except 4 studies.

Of interventions assessed, there were found to be not only cost effective, but also dominant treatments (ICER negative): ET over esophagectomy from a payer perspective in the USA (20), Statin therapy over no-statin therapy (23), and minimally invasive esophagectomy over open esophagectomy (30). Four economic evaluation studies were identified, the cost-effective strategy was sensitive to the age, cancer stage, comorbidity, tumor characteristics, clinician, and patient preferences (10, 19, 21, 26). The 7 included studies showed the cost-effective intervention: NCCRT compared to esophagectomy (22), the ECF regimen over FAMTX (24), CF regimen versus CCF in the first line of treatment for advanced esophageal SCC (25), SEMS over brachytherapy (27), Laser palliation (28) for incurable cancer of esophagus, and Brachytherapy over SES and laser therapy (13, 29).

5. Discussion

We conducted the first systematic review to evaluate the cost-effective treatments for esophageal cancer in the world in terms of economic evaluation studies. Of 2 487 records, 14 studies were included in the systematic review; more than half of the included studies (8/14) were conducted in UK and USA. The most perspective related to the health system (8 studies) and payer (4 studies) and 2 studies did not report the research perspective. Only 8 studies performed a sensitivity analysis. Ten studies used a threshold for analysis of cost-effectiveness. Different outcomes were applied, 8 studies had QALY outcome, 3 studies had a survival rate, and 2 studies had dysphagia score and quality of life.

Our results illustrated that the ET was superior to esophagectomy because it had been most effective and less costly. Furthermore, 4 included studies assessed the cost-effectiveness ET versus esophagectomy, Pohl et al. reported that ET compared with esophagectomy was more effective and less expensive (ICER negative) (20). Three studies show that ET was more cost-effective versus esophagectomy (10, 19, 21).

This finding is very important for decision-maker and health care manager in developing countries, countries located on the esophagus cancer belt, and countries where cost-effectiveness studies have not been done on esophageal cancer treatment.

First, studies have shown that using esophagectomy is greater than other treatments in developing countries, while the cost of this method is more than other treatments (31-33). Second, the survival rate for esophageal cancer is very low, the 5-year survival rate in the patient that cured with surgery was 40% (34), and it was 84% for patients that received endoscopic treatment (35). Of course, this should be taken into consideration that quality of life is an important factor in using therapeutic methods. Usually, the quality of life in patients who used surgical procedures is more than endoscopic treatment. For instance, Chu et al. showed that in T1b stage, the quality of life was 4.07 in esophagectomy and it 3.85 in endoscopic treatment (21).

The 5 economic evaluation studies compared palliative treatments; these studies showed contradictory results: Wenger et al. found that stenting was more cost-effective than brachytherapy (27), while McNamee and Seymour (13) and Da Silveira and Artifon (29) showed that brachytherapy was more cost-effective than stenting, laser therapy, and ablation. Moreover, Shenfine et al. reported that non-SEMS provided a higher cost and QALY comparing with SEMS (26). Xinopoulos et al. displayed that SEMS was cost-effective versus laser therapy (28). These results need to be interpreted with caution because there were various outcomes in the cited studies, QALY outcome in the studies of McNamee and Seymour (13) and Shenfine et al. (26), life years in Wenger et al. (27), and dysphagia in the Da Silveira and Artifon’s study (29); in addition, the cost of treatments is not similar in different studies.

Two included studies were identified, in which the adjuvant therapy was cost-effective. Fong Soe Khioe et al. stated that adjuvant statin + surgery was dominant over no-statin therapy (23). Lin et al. cited that NCCRT was more cost effective than surgery, with a $39 060 per life years (22).

Our systematic review shows that the number of studies conducted in developing countries is very rare, only one study was conducted in a developing country (Taiwan), and other studies were conducted in developed countries. Also, none of the 14 included studies have been conducted in countries located on the esophagus cancer belt. Furthermore, of 14 studies having eligibility criteria for the systematic review, more than half of the included studies (8/14) were conducted in UK and USA. Assessing this result suggests that esophageal cancer is still a major problem in developing countries and there is a needing for conducting cost-effectiveness studies in these countries.

There are some limitations in our systematic review. First, we cannot be sure that no relevant study has been lost from this article. However, for this purpose, we designed a comprehensive strategy of search in PubMed, Scopus, Cochran Library, EMBASE, and Web of science, the most comprehensive databases recommended for systematic review of economic evaluation (36-39). Second, we could not access the full-texts of 3 records on the economic evaluation of esophageal cancer treatment (40-42); therefore, we inevitably excluded them. Third, we could not perform any meta-analysis, there was high heterogeneity in the methodology of included papers of our systematic review. As result, the results were evaluated qualitatively.

6. Conclusions

This research is the first systematic review that assessed the economic evaluation of esophageal cancer treatment in the world. Among all the assessed studies, the endoscopic treatment was more cost-effective than esophagectomy, but there were contradictory results in palliative care for treatment of esophageal cancer. The cost-effectiveness of each intervention depends on the age of the patients, the cancer stage, comorbidity, tumor characteristics, and clinician and patient preferences.