1. Context

Palliative care is defined by the World Health Organization as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients with life-threatening illnesses and their families through prevention and relief of physical, psychosocial, and spiritual suffering (1). Palliative philosophy emphasizes perceiving dying as a normal phase in the timeframe of the end of life (EOL). Dying process of patients are not the same; so, health care providers should individualize the approach to this condition (2).

The good death is “dying free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and health care providers, in general, according to patients’ and families’ wishes, and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards” (3). Although achieving good death is one of the primary desires in palliative care, death may turn into a distressing situation or crisis that can be perceived by the dying patient, family members, or health care providers (2, 4-6).

Currently, Iran is categorized by The Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance as ‘isolated palliative care provision’ (7) with low supply and low demand for palliative care (8). Suitable models of palliative care for age-related or chronic medical conditions of Iran are not firmly established (9), and there is no clear vision or mechanism to achieve the strategy. However, there is a slow progress in this venue, and cancer palliative plans are leading.

According to The Economist Intelligence unit report in 2015, Iran ranked 73th among 80 countries in quality of death index (8). Obstacles to provide good death for Iranian palliative patients may be identified by extracting viewpoints of health care providers to imply applicable lessons regarding domestic resources and cultural grounds.

2. Objectives

The aim of the current study is to describe contributors to dying process crises through health care providers’ perspectives. This is achieved by interpreting the qualitative results of studies selected for meta-synthesis. The applicability of the extracted themes on cancer end of life care in the Iranian society are further discussed.

3. Data Sources

Search strategy was performed by PubMed, MedLine, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and PsycINFO databases. English articles published from January 2008 to March 2018 with keywords that included challenges OR crises OR experiences AND “dying process” OR “dying Patient” OR “end of life care” OR “terminal care” (MeSH terms) OR “attitude to death” (MeSH terms) AND “palliative care staff” OR hospice OR nurses OR physician. Additionally, the reference lists of all articles and related articles were reviewed.

4. Study Selection

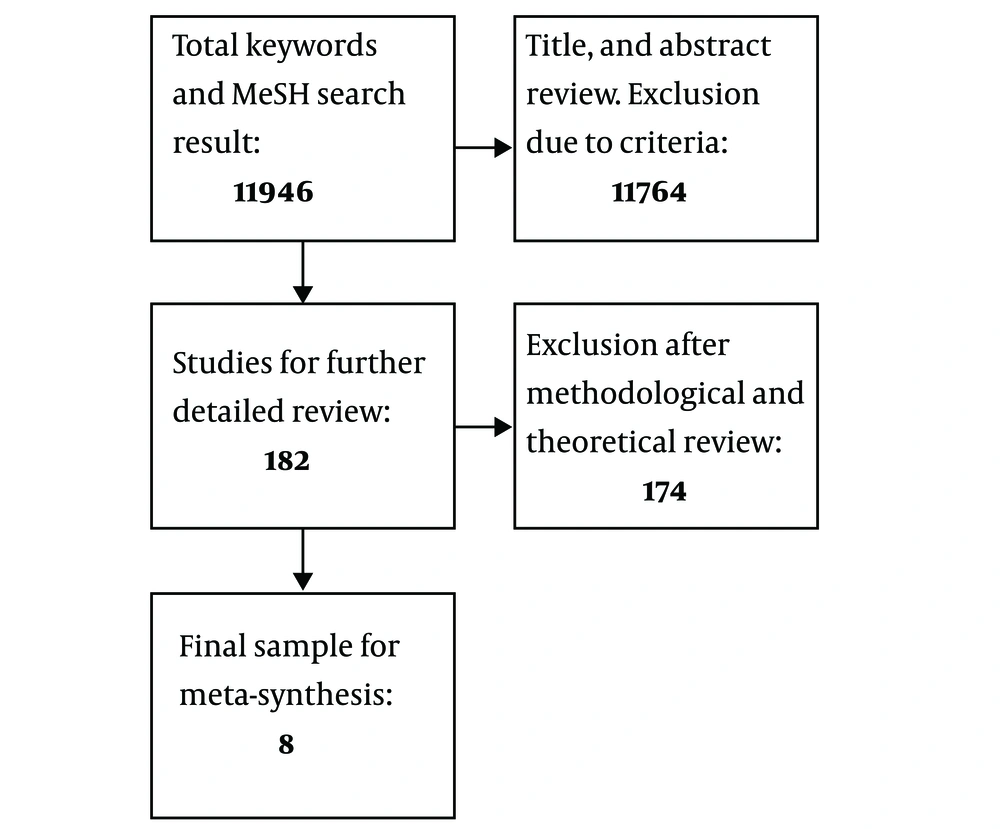

Primary search results were sought by the inclusion criteria: 1- qualitative articles that 2- measured challenges or crises of end of life care during the dying process of adult patients, in point of view of health care providers, which were 3- interview-based articles with 4- content analysis method, directed to the search question. Total sample included 1 1946 articles. Titles and abstracts were purposively read for excluding those that did not meet the inclusion criteria or were considered to have confounding properties or increased complexity of analysis. The exclusion criteria were categorized as 1- acute hospital or imprisonment, and other non-medical settings, 2- focused reports of any kind of volition or hastening death, such as assisted death, euthanasia, etc., 3- descriptive studies including families’ perspective, support, or participation for palliative care, 4- descriptive studies including dying patients’ perspective, spiritual beliefs, and dying experience, and 5- titles related to the structure or models of palliative programs. Consequently, 11 764 of them were excluded due to exclusion criteria, which resulted in 182 articles. At the final phase, again, abstracts and if needed, the main articles were reviewed methodologically and theoretically. Any of the articles unfocused on the research question were excluded. For instance, causative articles on ‘good death’ were omitted. By eliminating 174 more articles, 8 articles were entered in the study (Figure 1). Including all observed articles was the approach of sampling since it was inspected that the value of each article is prevailed in the phase of synthesis (10).

5. Data Extraction

This study was designed as a qualitative systematic review or meta-synthesis with thematic analysis approach. This is a method to analyze the data of qualitative studies in order to integrate the findings and interpret the results to a new deeper holistic concept. The stages of the study are described in the following sections. Coding of each article was performed through repeatedly reading each article to identify contributors to crisis in caring for dying patients in perspective of health care providers. The emerged data were summarized as descriptive themes and subthemes, which were subjected to thematic synthesis. In this process, reviewers defined concepts of one article and recognized the same concept in another, which is termed translating one study to another. This comparative process led to the production of common concepts as analytical themes. It was an inductive approach in order to go beyond the content of each article (11).

5.1. Rigor of Synthesized Data

Some of the defined core elements in critical appraise of findings of qualitative research are termed credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (10). In this study, the process of the data synthesis was held by two authors, who separately read the eligible selected articles and extracted result unprejudiced with their pre-understandings and self-ideas. Then, the results were discussed among the two to discover the reappearing data in consensus and to solve any possible conflicts. The credibility of this study was supported by this cause. Criteria for eligibility included articles, which homogenously investigated the same topic according to the study title and the predefined methodology; yet, demographic grounds may have been different. This was in regard of transferability of the results to other similar settings. The authors executed the method in a stepwise fashion to provide dependability of the study. The more the results were revised, the more they were rigorous in confirmability; thus, data were given to a third reviser at the final step for her approval.

6. Results

The ultimate sample included 8 qualitative English articles published between 2009 and 2016. Their sources were Google Scholar (4), PubMed (3), and ScienceDirect (1). In sample studies, dying process was evaluated in nursing homes (3), oncology wards (3), a general hospital (1), and a surgical ward (1). The authors and demographic characteristics of articles are listed in Table 1. Regarding the method of content analysis and its subtypes, 6 articles used thematic analysis, 1 used phenomenological hermeneutic approach, and another one used ground theory approach. The findings are summarized as descriptive themes and subthemes in Table 2. Table 3 lists the 8 created overarching themes that are described below.

| Authors (Ref No.) | Qualitative Methodology | No. | Age | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||||

| Dwyer et al. (12) | Focus group discussions | 20 | 30 - 40 | 16 | 4 |

| Iranmanesh et al. (13) | Narrative interviews | 15 | 32 - 50 | 11 | 4 |

| Ghaljeh et al. (14) | Semi-structured interviews | 18 | mean: 32 | ||

| Andersson et al. (15) | Descriptive method, interviews | 6 | 22 - 42 | 5 | 1 |

| Jenull and Brunner. (16) | Semi-structured interviews | 17 | 21 - 56 | N/A | N/A |

| Dong et al. (17) | Semi-structured interviews | 15 physicians | mean: 34 | N/A | N/A |

| 22 nurses | mean: 29 | ||||

| Peterson et al. (18) | Audiotaped in-depth interviews, online open-ended surveys | 15 | 20 - 54 | 12 | 3 |

| Cagle et al. (19) | Open-ended surveys | 707 | 31 - 50 | 93% | 7% |

| Authors (Ref No.) | Original Themes |

|---|---|

| Dwyer et al. (12) | |

| 1. Alleviating suffering and pain | |

| Feeling powerless regarding symptom control | |

| Lack of knowledge and education on symptom control | |

| 2. Finding meaning in everyday life | |

| Existential anxiety | |

| Fear of being alone | |

| Lack of health care providers’ time to sit and listen to the patients’ story | |

| 3. Revealing thought and attitude about death | |

| Lack of knowing what patients think about their imminent death | |

| What they wish to arrange beforehand | |

| 4. Caring for the dead person’s body | |

| Make death into something more pleasant | |

| Paying attention to different rituals | |

| Grieving for the dead person | |

| Feeling of emptiness due to their relationship with the person | |

| 5. Coping with the gap between personal ideals and reality | |

| Feelings of guilt because they had not been with the person when he/she died | |

| Feelings of guilt because they would have done more for the dead person | |

| Accept death as a part of their job | |

| More training and education were needed to provide end of life care | |

| Not being able to provide the care they wished for | |

| Iranmanesh et al. (13) | |

| 1. Being attentive to dying persons and their families | |

| Relieving the spiritual pain | |

| 2. Being cared for by the dying people and their families | |

| Decreasing the fear of death | |

| Becoming strong against personal difficulties | |

| 3. Being faced with barriers | |

| Limited time to make on interaction with patients | |

| Lack of nurses’ autonomy | |

| Lack of desirable environment | |

| Lack of palliative care | |

| Lack of public education about end of life care | |

| Ghaljeh et al. (14) | |

| 1. Environmental structural challenges | |

| a. Physical challenges | |

| Lack of palliative care centers | |

| Unsuitable and stressful space of the wards | |

| b. Equipment challenges | |

| Lack of technology | |

| Lack of required facilities in the wards | |

| 2. Cultural challenges of the organization | |

| c. Human resource challenges | |

| Lack of organizational support for staff | |

| Shortage of human resources | |

| Lack of skills in the use of equipment and technology | |

| Lack of effective communication | |

| Lack of staff’s independence while they have knowledge and skills | |

| d. Structural challenges of rules and regulations | |

| Rules prevent the presence of family besides patients | |

| Rules prevent optimal care | |

| Pay more attention to writing tasks instead of being with patients | |

| e. Management challenges | |

| Managers’ lack of attention to the empowerment of nurses to perform tasks with skills | |

| Nurses lack of support by the managers | |

| 3. Educational challenges | |

| End of life care training during nursing education | |

| End of life care training at the beginning of work at the ward | |

| End of life care training and updating during nursing practice. | |

| Andersson et al. (15) | |

| 1. Being supportive in caring process | |

| By education and practical knowledge | |

| By preventing loneliness in end of life situations with spending more time with patients | |

| By being aware of patient’s emotions, wishes, and needs in caring process | |

| 2. Being frustrated in caring process | |

| Difficult to satisfy different patients’ needs simultaneously | |

| Moving from cure to care cause emotions to go up and down | |

| Less support for palliative care | |

| Lack of knowledge and skills | |

| Insufficient symptom control | |

| Difficulties in discussing death and dying with patients and their families | |

| 3. Being sensitive in caring process | |

| To make dying process calm and peaceful | |

| To satisfy patients and families regarding end of life | |

| Personally affected because of awareness about their own mortality | |

| Difficult to leave thoughts of dying situation even after working hours | |

| Jenull and Brunner (16) | |

| 1. Contact with dying residents | |

| Sudden and unexpected death of residents | |

| Emotional involvement in long and painful dying process | |

| 2. Contact with family members | |

| Relatives who could not accept the patient’s death | |

| Relatives grief in situations involving death | |

| 3. Separating private life from work | |

| Difficulties in forgetting stressful work-related experiences | |

| 4. Need of help from outside | |

| Role of collaboration with physicians, religious groups, and palliative care team | |

| Dong et al. (17) | |

| 1. Strong senses of obligation and crisis | |

| Presence and availability at the patients’ bedsides sense of crisis cause extra pressure on health care providers | |

| 2. Hope and spirit maintenance | |

| Death denying | |

| Strengthening inner energy | |

| Spiritual care | |

| 3. Improvement of quality of life | |

| Control of physical symptoms | |

| Providing comfort | |

| 4. Promotion of family function | |

| Encouragement of being with dying patients | |

| Encouragement of patient care and advocating | |

| Family preparedness for impending death | |

| 5. Dilemmas during end of life stage | |

| Communication in the cultural context | |

| Inexperienced in psychological care | |

| Peterson et al. (18) | |

| 1. Personal concerns | |

| Not having enough time to adequate care of dying patients and their families | |

| Fear of lacking experience in caring dying patients | |

| Not being able to maintain professional distance while caring for dying patients and their families | |

| 2. Concerns about the patient | |

| Make sure they did everything to alleviate patients’ physical and emotional suffering | |

| Make sure that patients received the information they needed and wanted | |

| Make sure that patients felt comfortable talking with nurses and sharing information | |

| 3. Concerns about family | |

| Make sure to have adequate time for family | |

| Help family members to cope with the loss of their loved one | |

| Difficulties in initiating discussion with family members | |

| Educate and address uncomfortable issues | |

| Mediate conflicts between the patient and family members to ensure that the voice of patient was heard | |

| Cagle et al. (19) | |

| 1. Witnessing distressing signs and symptoms | |

| 2. Feeling helpless | |

| Unable to provide comfort | |

| Cannot stop “the inevitable” | |

| 3. Target of anger, criticism, or rudeness of patients and their families | |

| 4. Unacknowledged death | |

| 5. Not being present for the patient | |

| 6. Dealing with challenging aspects of care | |

| When care causes discomfort | |

| Lack of end of life care knowledge (medication dose/dying process) | |

| 7. Bad timing | |

| Unexpected death | |

| 8. Hospice involvement or not | |

| 9. Uncertainty | |

| About prognosis | |

| Whether patient is comfortable | |

| 10. Communication challenges | |

| Lapses with patient and families | |

| Having difficult conversation | |

| 11. Painful emotions | |

| 12. Family discord |

| New, Overarching Themes | Extracted Original Themes (Authors and Publication Year) |

|---|---|

| 1.Poorly controlled symptoms | |

| 1.1. Alleviating suffering and pain (Dwyer et al. 2010) (12) | |

| 1.2. Insufficient symptom control (Andersson et al. 2015) (15) | |

| 1.3. Emotionally involved in long and painful dying process (Jenull and Brunner 2015) (16) | |

| 1.4. Control of physical symptoms (Dong et al. 2015) (17) | |

| 1.5. Providing comfort (Dong et al. 2015) (17) | |

| 1.6. Make sure they did everything to alleviate patients. Physical and emotional suffering (Peterson et al. 2010) (18) | |

| 1.7. Witnessing distressing signs and symptoms (Cagle et al.2016) (19) | |

| 1.8. Uncertainty whether patient is comfortable (Cagle et al.2016) (19) | |

| 2. Unexpected death | |

| 2.1. Sudden and unexpected death of residents (Jenull and Brunner 2015) (16) | |

| 2.2. Unacknowledged death (Cagle et al. 2016) (19) | |

| 2.3. Unexpected death (Cagle et al. 2016) (19) | |

| 3. Time and facility constraints | |

| 3.1. Limited time to make an interaction with patients (Iranmanesh et al. 2009) (13) | |

| 3.2. Lack of desirable environment (Iranmanesh et al. 2009) (13) | |

| 3.3. Lack of palliative care (Iranmanesh et al. 2009) (13) | |

| 3.4. Shortage of human resources (Ghaljeh et al. 2016) (14) | |

| 3.5. Lack of time due to pay more attention to writing tasks instead of being with patients (Ghaljeh et al. 2016) (14) | |

| 3.6. Not having enough time to adequate care of dying patients and their families (Peterson et al. 2010) (18) | |

| 3.7. Not being present for the patient (Cagle et al. 2016) (19) | |

| 3.8. Unsuitable and stressful space of the ward (Ghaljeh et al. 2016) (14) | |

| 3.9. Equipment challenges (Ghaljeh et al. 2016) (14) | |

| 3.10. Less support for palliative care (Andersson et al. 2015) (15) | |

| 3.11. Difficult to satisfy different patients’ needs simultaneously because of time constraints (Andersson et al. 2015) (15) | |

| 4. Lack of education or knowledge | |

| 4.1. More training and education were needed to provide at end of life care (Dwyer et al. 2010) (12) | |

| 4.2. Public education about end of life care (Iranmanesh et al. 2009) (13) | |

| 4.3. Educational challenges (Ghaljeh et al . 2016) (14) | |

| 4.4. Being frustrated in caring process due to lack of knowledge and skills (Andersson et al. 2015) (15) | |

| 4.5. Lack of experience in caring dying patients (Peterson et al. 2010) (18) | |

| 4.6. Lack of end of life care knowledge, medication dosing, and dying process (Cagle et al. 2016) (19) | |

| 5. Weak coping skills | |

| 5.1. Grieving for the dead person (Dwyer et al. 2010) (12) | |

| 5.2. Feeling of emptiness due to their relationship with the patient (Dwyer et al. 2010) (12) | |

| 5.3. Coping with the gap between personal ideals and reality (Dwyer et al. 2010) (12) | |

| 5.4. Help family members to cope with the loss of their loved one (Peterson et al. 2010) (18) | |

| 5.5. Coping with their own painful emotions(Cagle et al. 2016) (19) | |

| 5.6. Being personally affected by dying patients (Andersson et al.2015) (15) | |

| 5.7. Sense of crisis cause extra pressure on health care providers (Dong et al.2015) (17) | |

| 6. Communication barriers | |

| 6.1. Lack of effective communication (Ghaljeh et al.2016) (14) | |

| 6.2. Difficulties in discussing death and dying with patients and their families (Andersson et al. 2015) (15) | |

| 6.3. Being sensitive to satisfy patients and families regarding end of life (Andersson et al. 2015) (15) | |

| 6.4. Making sure that patients received the information they needed (Peterson et al. 2010) (18) | |

| 6.5. Difficulties in initiating discussion with family members and patients (Peterson et al. 2010) (18) | |

| 7. Family conflicts | |

| 7.1. Rules prevent the presence of family beside patients (Ghaljeh et al. 2016) (14) | |

| 7.2. Contact with family members (Jenull and Brunner 2015) (16) | |

| 7.3. Mediate conflicts between the patient and family members (Peterson et al. 2010) (18) | |

| 7.4. Promotion of family function (Dong et al. 2015) (17) | |

| 7.5. Family discord (Cagle et al. 2016) (19) | |

| 8. Systematic issues | |

| 8.1. Management challenges (Ghaljeh et al. 2016) (14) | |

| 8.2. Being target of anger, criticism or rudeness of patients, and their families (Cagle et al. 2016) (19) |

6.1. Poorly Controlled Symptoms

This theme produced 6 of references across 8 studies. In one study, all the health care providers declared that minimizing dying cancer patients’ suffering is a core responsibility (17), and their duty is to do “everything they could do” to alleviate suffering (18). The fear and suffering of patients with prolonged death was described as “terrible” (16). Staff members declared that “witnessing” physical deterioration, distressing uncontrolled symptoms, and patients’ death were disturbing (19). The duty is a burden to some nurses, who described that failure for providing good symptom control caused feelings of being “powerless” or “helpless” (12, 15).

Making a compromise between providing physical comfort and discontinuation of inappropriate interventions can always be difficult. One report stated that resuscitation and another aggressive treatments did not significantly extend dying patients’ lives instead a “comprehensive management” was successful to alleviate the patients’ pain and to offer maximal physical comfort rather than application of unnecessary interventions (17).

6.2. Unexpected Death

Inappropriate estimation of terminal phase or other sudden events like pulmonary thromboembolism, acute myocardial infarction, etc., is quite common and causes 5% to 10 % of deaths in the palliative care setting (20). Unacknowledged death and “bad timing” were noticed as negative experiences in caring for dying patients (19). One of the staff described the stressful and horrifying condition of finding residents already dead when it was unpredicted (16).

6.3. Time and Facility Constraints

Limited time was a barrier to adequate care for dying patients across 5 articles. For most of the nurses, being absent for the patient and their families was stressful (18, 19). Shortage of nurses, heavy workload (13-15), and too much documentation duties were considered time-consuming and made much separation (14).

Facility constraints such as lack of desirable environment to focus on people’s special needs during the process of death were described as a barrier by most participants. Nurses stated that lack of palliative care centers caused EOL patients die next to other patients in stressful wards. This intensified anxiety and frustration and, subsequently, influenced quality of care (14, 15). Using life-prolonging strategies in oncology wards with no palliative intention for patients and their families was time- and energy-consuming and led to involved members became worn-out while the patient suffered an uneasy death (13).

6.4. Lack of Education or Knowledge

Lack of knowledge on basic viewpoints on dying process and medications provided in terminal phase may contribute to not providing the best care for dying patients (18, 19), particularly for new staff, who may need more training (12). Some nurses pointed out that their frustration stems from lack of skillfulness in palliative and terminal phase care (15). In one study in Iran, nurses expressed that lack of EOL care training during their nursing courses caused challenge at the beginning of their work and throughout their nursing practice (14). In another study in Iran, nurses emphasized the necessity of public awareness about EOL care for patients with cancer in order to facilitate people’s legitimate acceptance of the practice (13). Patients and families should be informed about what to expect and what care is available at this stage (12).

6.5. Weak Coping Skills

Coping strategies help palliative care staff and family health care providers to deal with stressful experiences. In one research, effective coping responses around sensitive areas of EOL care were thought to be the most challenging topic even for the experienced (17). Some nurses paid unusual attention to their patient when they were noticed that he or she was dying (15). They expressed a feeling of hollowness due to loss of contact with that person after a person’s death. Nurses described their difficulties maintaining an emotional distance (17, 19). Some participants wished that they would have done more for the person that already died. They expressed feelings of guilt because they had not been with the person when he or she died (12). Some were hit personally and had feelings of solicitude of their own and their family’s death. Negative thoughts around dying and terminal phase frequently remained after working hours (15). The nurses were also concerned with the needs of the family. They expressed their desire to get them involved with the situation and help them cope with their loss of a loved one (18).

6.6. Communication Barriers

Preparing patients and their families for EOL through effective communication decrease their fear and anxiety, and facilitates the caring process. Nurses said that caring for satisfaction of patients and relatives at terminal phase of the disease is a requirement of EOL care qualification. Nevertheless, they described difficulties in discussing death and dying. Sometimes, they did not know what to say when they aimlessly used a trial and error strategy within these conversations (15). Initiating discussions with patients and family members were sometimes difficult. They hesitated to start conversation and overthought their words (17); hence, for making sure that the patients felt comfortable, talking with them and giving the information they wanted were among the major communication concerns that nurses concerned (18). Experiences show that shortage of personnel and heavy workload negatively affected judgment of patients toward the health care team and caused complaints (14, 21).

6.7. Family Conflicts

Conflicts between family members themselves or family members and health care team stem from unsuccessful communication or different views on terminal illnesses, dying process, life sustaining treatments, and patients’ needs (21). In most of these situations, nurses were concerned that voices of the patients may not be heard. Nurses often felt compelled to mediate conflicts and follow prescriptions. This was sometimes difficult (18). One nurse described feeling helpless when the family refused morphine administration, while she was witnessing a dying resident’s discomfort. Her family believed that “she is out of it, she probably isn’t in pain” (19).

Preparing the families for death and making it peaceful is a professional duty for the health care team. Nurses were concerned with being attentive to the needs of the family. People in different stages of grief should be treated differently. This requires explaining uncomfortable issues with family to unify them and prepare them for what is going on (17, 18).

6.8. Systematic Issues

Organization support for staffs is an important issue, which can impact on motivation and performance of the team and support them from occasional aggression. Systematic barriers target ambitions of the personnel. Managers’ neglect to the empowerment of nurses may become the cause of challenges (14). Ineffective effort for convincing the families, or their remaining in anger state of grief may eventually lead to offence. Staff members shared their experience about defenselessly being targeted by patients or family irrational blame and “not understanding why we cannot stop the inevitable” (19). Restricted visiting hours, or regulations that prevent families from being beside dying patients were also described as structural challenges (14).

7. Discussion

Peaceful death is one of the primary desires of palliative care. This objective is not always met and sometimes death of a terminal patient turns into a clinical crisis. The significance of interpreting aspects of this failure is to understand similar conditions and extrapolate solutions. This is discussed in the following section in accordance to our findings and with a main focus on Iranian cultural scheme.

Poorly controlled symptoms, unexpected death, time and facility constrains, lack of education or knowledge, weak coping skills, communication barriers, family conflicts, and systematic issues are main overarching themes that were revealed from this study.

Wallace et al. provided a comprehensive understanding of dying experience in nursing homes in the United States of America in perspective of staff, residents, and family members. They synthesized 13 qualitative articles. The extracted themes were staffing issues, knowledge about symptom management, formal training in palliative care, nursing homes’ physical environment, federal regulations, advanced care planning, family issues, changes in care conditions by hospitalization, disease progression to a palliative state, transition to hospice, cognitive appraisal, and coping responses (4). These findings are similar to our synthesis, to some extent, regarding most themes with the exception of difference of federal regulations, advanced care planning, and transition to hospice. The unshared themes show the importance of regulatory standards, patient autonomy, and realizing patient disease states. In another study, Zheng et al. categorized new graduated nurse’s experiences, while encountering death of patients via qualitative meta-synthesis of 6 studies. The 6 main themes included emotional experience, importance of facilitating a good death by alleviating physical and emotional suffering, paying attention to support the dying patient’s family, providing a qualified EOL care through a good educational program, personal and professional growth, and coping strategies. Reported experiences were mostly negative and the authors strongly recommended mentors to provide emotional or professional support and encourage for the graduates to acquire more skills in EOL care via educational programs (22).

Among the identified themes, poorly controlled symptoms, especially pain and other physical and emotional symptoms, were perceived the most dominant issue that lead to crisis during dying process (12, 15, 17, 18). Pain is one of the most common symptom in patients with advanced cancer, especially at the last week of life that is experienced by 70% to 80 %. Uncontrolled pain and other symptoms have become an indicator of poor qualified EOL care (21, 23-25). Robust educational programs improve symptom control and also accuracy in prognostication and estimation of the terminal phase and can reduce unexpected death.

Terminally ill patients and EOL care providers need the last hours of lives of patients elapse with excellent standards according to the dying process (13); however, unfortunately, in Iran the national capacity to deliver palliative care to patients in need is extremely low and public has almost no understanding of palliative care services. Iran has limited specific milestones to achieve a government-led strategy for palliative care and its programs for access to palliative services are also limited (8). Efforts for documentations, and augmenting regulatory standards, besides considering patient autonomy, that were extra-themes that Wallace et al. reported (4), are though not generally applicable in context of Iranian palliative scheme because of current systematic limitations; however, if achievable, they theoretically may reduce much of the death crises.

Cultural issues influence how families expect, perceive, and express death (21) and, therefore, cultural values in each region can affect the process of achieving good death. Patients with different spiritual backgrounds need different approach in providing EOL care (26). The dominant religion of the Iranian is Islam with sectarian minorities around 1% to 2% (26). In Islamic culture, it is believed that the moment of death is predestined by God, but praying may at least comfort the dying patient and family members or may cause longevity (27, 28). Reliance on fate of a supernatural authority may improve coping responses confronting death and, therefore, it may reduce much of tension for the palliative care system. Rituals such as recitation the Qur’an, the holy book of Muslims, and repositioning the dying patient toward Mecca is common practice beside the dying patient (26, 29). Space and compliance for satisfying spiritual and other needs of the patients and families should be sought in advance in palliative care units.

Many Iranian families are over supportive to their extremely ill patients and their role in decision making is prominent. Some may request extra care, and according to minor folk beliefs, some feel committed to stand pain and accept their will because perceiving pain is atonement for sins (26). This belief may help with endurance of the situation by patient and families. Conversely prejudice beside bureaucratic red tape are major barriers to adequate opioid pain management in Iran (8). Fear of addiction is also frequent among families (9).

Most dying patients wish to stay with their family member’s until the last moment (26, 30). Well cooperative families can take major part in satisfying emotional and spiritual needs of Iranian patients and even palliation of symptoms. Hospital-based home care approaches are emerging in Iran. One of the first and formalized palliative care programs in Iran is held in Imam Khomeini Hospital Cancer Institute (31), which delivers cancer symptom control, respite, and terminal care. It also educates families for independent symptom control during the terminal phase in home setting. Reports show that it had actively serviced more than 2500 patients with advanced cancer since 2007. Consistently, it is documented that 90% of the registered patients passed away at home by their own desire (9).

Culture can influence optimal care negatively. In Iran, cancer diagnosis is frequently undisclosed by family members. It is not uncommon for health care providers to meet patients that were kept unaware, but they are eager to know about their illnesses and treatment. Requests for withholding symptom control or not telling the truth by family members may cause ethical paradox. Truth telling is frequently compromised by physicians for ethical principle of “lack of harm” for their patients’ or other relatives’ mentality. This is because according to Iranian culture, many believe that disclosure creates distress and hopelessness (26) and there is evidence that it reduced quality of life (28). However, a national survey in Iran showed that most patients with cancer were willing to receive information about their disease, while less than half of the patients were aware of their condition (29). There is no formal social and ethnical training prioritized for doctors and nurses to deliver bad news (26) and since health care providers, patients, and each family member may value EOL care differently, inappropriate pedagogy causes miscommunication (21), that can be perceived as disrespectfulness to families.

Communication is a cardinal element in EOL care. The process comprises transferring the needed information and responding to emotional reactions to the new situation. Meetings should be individualized to the patients and also cultural and family backgrounds. It is widely accepted that conducting one or more family meetings is effective (32, 33). In fact, involving family members that are sometimes unaware or deny their patients’ condition enables them to prepare for an impending death. Once reactions have settled, their understanding and preparedness for further decisions would be rechecked. This process can improve coping process and help with appropriate decision making (21).

One can expect from the timing of the events that symptom control or at least causing less suffering is essential to prevent cascades of crises or rises thresholds of consequences. However, as most palliative patients deal with many complications of medical illnesses, the practice of symptom control may become ineffective at a time when the family members and health care providers should be prepared. In view of health care providers, witnessing a distressful dying patient can already be painful (16, 19). This becomes more intense when death happens unexpectedly (16), and at the same time, there are constrains in space, time, and personnel acquisition (14). The situation becomes catastrophic when there is lack of knowledge on how to control it, there is no good coping skill, and when public knowledge about terminal phase is scarce (13, 18). When family members do not share a single voice, and there is lack of a systematic palliative structure for resource acquisition the condition is exacerbated.

The evaluation of the current meta-synthesis was limited to view points of health care providers, nurses, and physicians with diverse environmental characteristics that may have interfered with a general assumption for implicating it on an Iranian palliative framework for cancer care. In addition, a strict criterion for controlling the quality of selected articles except from the quality of database of the articles was not used. Accrual of perspectives of patients and family members in future studies renders added value. Furthermore, it is suggested to launch deductive approaches for analyzing Iranian existing palliative strategies. In other words, refining palliative frameworks by collective data helps with improving much of constrains in Iranian palliative setting.

8. Conclusions

It can be concluded that the first priority to prevent uncontrollable crises is good symptom management, and planning family meetings to have an appropriate conversation with patient and families is the second. The health care team should be prepared for EOL care and trained for timely efficient communication and coping strategies in the context of cultural beliefs. Moreover, involving a psychiatrist in palliative care team may effectively help with uncompleted coping processes. Finally, environmental barriers were noticed by the staff to be obstacle to deliver qualified EOL care and should be considered according to cultural needs. Engaging families in continuum of care according to high bond of Iranian patients to their families, and conducting family conversations in order to minimize any possible cultural conflicts can help with the improvement of Iranian palliative structure.