1. Background

In Iran, cancer is the third leading cause of death after heart disease and accidents (1). In order to treat cancer, a wide range of medical treatments and drugs are used, which are followed by some complications while being effective (2). Therefore, many cancer patients have been using complementary medicine for a variety of reasons, including the medical treatment’s not being effective, concerns about the complications of routine treatments, and symptom management (3, 4). Complementary medicine is defined as actions or products that are not classified in conventional treatments and includes a range of treatments such as mind-body medicine, biological treatments, whole medical systems, energy therapy, and manipulative treatments, which are used by cancer patients (5).

In developing countries, the use of complementary medicine has been reported by one third to half of cancer patients, which may be related to the clinical setting (the type and progress of the disease) and the phase of treatment (diagnosis, active treatment, during recovery, and palliative care) (6). In some societies, religious beliefs make patients feel that using these methods is more consistent with their beliefs (7).

In recent years, the public acceptance of these methods has increased, considering the studies indicating the effectiveness of these methods in controlling some complications (8), such as their effectiveness in improving the physical condition (9), improving the quality of life, and reducing anxiety, depression, and fatigue (10). So, even though the traditional medicine in Iran had been forgotten for a while despite its several hundred years of background, it has been restored based on the WHO’s recommendations on the development of indigenous knowledge and the use of complementary medicine. Today, specialists are being trained in this area in several well-known universities in Iran (11).

The results of the conducted studies show that Iranians have a positive attitude towards complementary medicine and the demand for such therapies is increasing (12). However some of them have methodological limitations like using questionnaires, which are not validated as well as the limited number of participants that prevent generalizing the results (13).

Despite this luck, it is worth noting that the majority of the patients using this type of treatment have limited knowledge of it (14, 15), are unaware of its potential complications, and most of them do not inform their physicians that they use these types of treatment (12, 16, 17). This can put patients, using such methods at risk and exposed to potential complications (18).

Some of these methods may reduce the effectiveness of chemotherapy drugs (19) or cause interactions with chemotherapy drugs and stimulate the growth of malignant tissues (20, 21). In some circumstances, patients see themselves needless of medical treatment protocols and stop them before the due time (22).

Therefore, in order to ensure the safe and effective use of complementary medicine, it is necessary to identify the extent, to which they are used, as well as why and how they are used among patients (23). On the other hand, the care providers’ awareness of the current status of using complementary medicine in cancer patients can lead to their getting familiar with patients’ preferences and guide them in making decisions about using them for patients (24).

2. Objectives

Since the analysis of the awareness of complementary medicine users can be the first step in planning to use its helpful aspects and to limit its non-scientific methods of application, this study aims at investigating the perspectives of cancer patients regarding using complementary medicine.

3. Methods

This is a descriptive study, and its population consists of all cancer patients admitted to the selected teaching hospitals throughout the country.

Purposeful sampling was performed according to the inclusion criteria. At the time of diagnosis, the patients were above 20 years, diagnosed with cancer for at least 1 year, and were familiar with complementary medicine in their own opinion. To this end, sampling was done in 13 cities in Iran, which had hospitals equipped with oncology departments and clinics. Finally, 176 patients meeting inclusion criteria entered the study.

The questionnaires used in this study included demographic characteristics questionnaire and Questionnaire on Integrating Complementary Medicine in Oncological Treatment. The demographic characteristics questionnaire was designed by the research team. The instrument applied in this research, Questionnaire on Integrating Complementary Medicine in Oncological Treatment, has been developed by Ben-Arye et al. and used in various studies (25). At first, a comprehensive review was conducted on the literature on cancer patients’ perspective in the Middle-East and in the world. Subsequently, in-depth individual interviews were done with 24 cancer patients, 22 oncology care providers, 14 healthcare providers experienced in cancer care (para-clinical therapists), and 25 complementary medicine physicians and therapists. Then, 3 focus groups were created, including oncologists, social workers, and the managers of health centers. A preliminary draft of the tool was designed in the form of one focus group, consisting of 5 cancer patients, whose views were applied to improve the comprehensiveness of the tool. Finally, the designed tool was reviewed and approved by a number of care providers in order to finalize the conclusion (25).

Regarding the purpose of this study, some parts of the scale were translated into Persian and psychometrically evaluated. This section contains 36 items as follow: A yes/no question, about the use of complementary cancer therapies now or over the past year, and 11 questions about the use of the various complementary therapies that one currently uses. One question is whether patients are skeptical about using complementary medicine, which were answered with 2 options, yes and no; they were asked if complementary medicine is used as part of cancer treatment services, do they consider using it? Another question was related to the person, who consulted him for carrying out complementary medicine. They were, then, asked to list the symptoms they expected to improve with complementary medicine in the form of 21 items. In order to examine the validity of the scale, 15 university faculty members, experts in complementary medicine, and its implementation were asked to express their comments and suggestions in terms of grammatical points and using proper words in line with the culture of the community after studying the scale. Ten cancer patients were also asked for their opinions in order to determine the difficulty level of phrases, and the degree of mismatch, and to discover any ambiguities. For examining the internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated and the above-mentioned scale was provided for 20 patients. After completing the scale, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated to be 0.84 (α = 0.84). In order to determine the stability, the questionnaire was provided for the 20 patients, twice within 2 weeks. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was measured to be 0.68 (ICC = 0.86), using one-way random effect models (ICC = 0.68) in both sessions of performing the test, with a confidence level of 0.95. The approximate time for the completion of each questionnaire was 20 minutes.

The data were analyzed, using SPSS 20 software. Descriptive statistics (frequency, ratios, percentage, mean, variance and standard deviation) were used to answer the research’s descriptive questions.

3.1. Ethical Considerations

This study is the outcome of the research proposal of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences under the ethical code IR.SBMU.PHNM.1395.562. After providing the participants with necessary information on research goals, and how to perform it and obtaining informed consent from them, the researchers offered the questionnaires. They also assured the participants of the anonymity of the questionnaires and the confidentiality of the gathered data.

4. Results

The mean and standard deviation of the age of the participants in the study was 53.14 ± 13.65. Generally, 54.5% of the participants were male and other demographic information is given in Table 1.

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| < 40 | 28 (15.9) |

| 41 - 50 | 47 (26.7) |

| 51 - 60 | 40 (22.7) |

| 61 - 70 | 50 (28.4) |

| > 71 | 11 (6.3) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 80 (45.5) |

| Male | 96 (54.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 56 (31.8) |

| Married | 93 (52.9) |

| Divorced | 27 (15.3) |

| Educational level | |

| Primary school | 64 (36.3) |

| High school | 67 (38.1) |

| University | 45 (25.6) |

| Religion | |

| Shia | 123 (69.9) |

| Sunni | 26 (14.8) |

| Christian | 13 (7.4) |

| Others | 14 (7.9) |

| Stage of treatment | |

| Before chemotherapy | 35 (19.9) |

| Middle of chemotherapy | 45 (25.6) |

| At least 6 month after chemotherapy | 42 (23.8) |

| Middle of radiotherapy | 25 (14.2) |

| Just monitored | 29 (16.5) |

Among the population under study, 65.6% were currently using complementary therapies for cancer, or had used them over the previous year.

The most frequently-used medical treatment was herbal and the least-used ones were homeopathy, anthroposophy medicine, and aromatherapy (Table 2).

| Complementary Medicine Treatment Related to Cancer | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Medicinal herbs | 85 (48.3) |

| Nutritional counseling | 70 (39.8) |

| Chinese medicine (acupuncture) | 14 (8) |

| Anthroposophic medicine (e.g. injections of Viscum, Mistletoe, Iscador) | 0 (0) |

| Treatments using relaxation, guided imagery, meditation | 28 (15.9) |

| Traditional & folk treatment (e.g. traditional Arabic medicine, traditional Jewish medicine, “kitchen remedies”, folk/traditional healers, etc.) | 48 (27.3) |

| Nutritional supplements at health food stores for cancer treatment | 30 (17) |

| Touch and movement therapies (e.g. reflexology, yoga, shiatsu, etc.) | 48 (27.3) |

| Healing and energy (e.g. magnets, Reiki, Bicomb) | 36 (20.5) |

| Art therapies(e.g. drawing, music, dance) | 32 (18.2) |

| Homeopathy | 1 (0.6) |

| Treatments using naturopathy, aromatherapy, Bach remedies | 0 (0) |

Generally, 59.7% of the samples had no doubt about using complementary medicine as a principle for the treatment of cancer, and often (39.2%) reported that they will accept complementary medicine if it is provided as a part of cancer treatment services and tend to follow this type of treatment. While 51.71% of research samples had consulted with a complementary medicine specialist, seeking advice on using it for cancer treatment.

| Health Care Provider | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| A qualified complementary medicine practitioner | 91 (51.71) |

| A folk healer (practicing traditional medicine) | 42 (23.86) |

| My family doctor | 26 (14.77) |

| A doctor, who practices complementary medicine | 17 (9.66) |

| Total | 176 (100.0) |

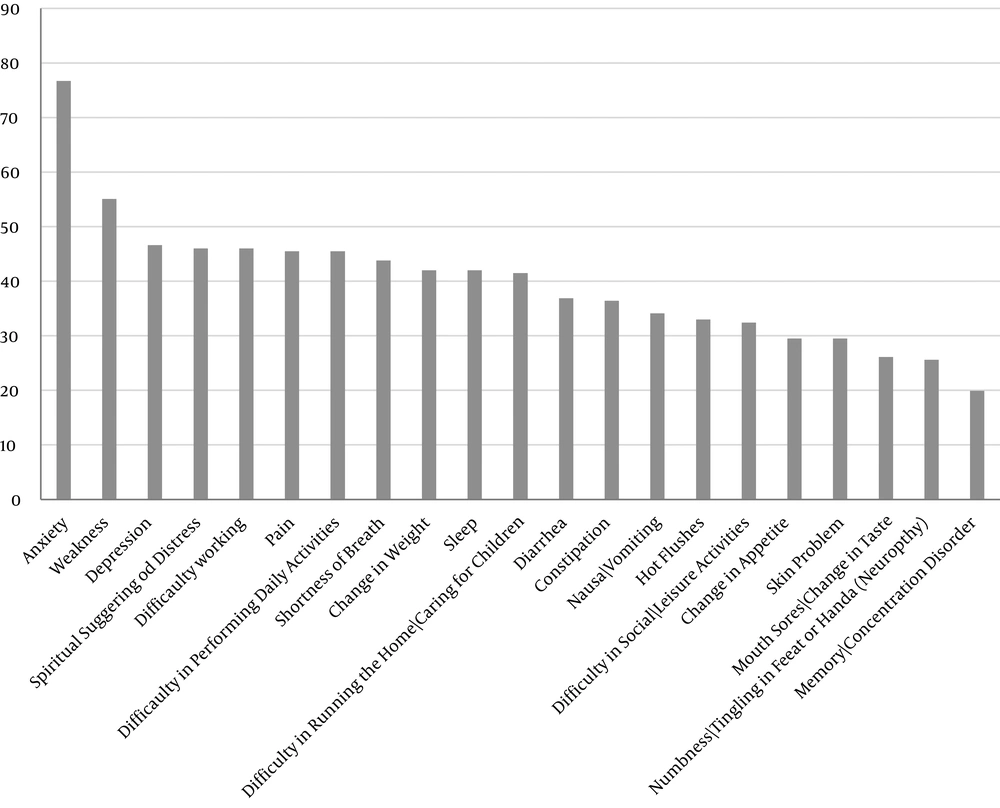

Research participants expected the use of complementary medicine to improve their daily performance. Their experiences showed that anxiety, fatigue, and depression improved more than other symptoms did. Complementary medicine had the least effect on tingling in feet or hands (neuropathy), and memory and concentration disorders. Other items are shown in Figure 1.

5. Discussion

Today, the use of complementary medicine has increased among cancer patients, especially in the Middle-East (6), with the aim of reducing the complications of oncology treatments and improving the quality of life for many of them (25, 26). However, the lack of awareness of the potential complications of this type of treatment and its improper implementation are considered to be important challenges (27). Therefore, the present study aims at investigating cancer patients’ perspective on using complementary medicine.

The results of this study showed that most of the patients under study were currently using complementary therapies for cancer or had used them over the previous year. In fact, the use of complementary therapies is widespread in the Middle East, with rates ranging from 35% in Iran (28), 57% in Turkey (29), and 90% in Saudi Arabia (30). However, according to reports, the rates are low in some European countries such as Switzerland, England, and Greece (31), which can be explained by socio-cultural differences and access to these treatments. Traditional medicine and its related approaches, such as herbal remedies, are part of the history of medicine in the countries of this region, which have been gradually transferred from eastern countries to the west. On the other hand, differences in the design of studies and the definitions of complementary medicine can also cause difference in the results of the studies conducted on the prevalence of using complementary therapies (32).

Among the various methods of implementing complementary medicine, the two most commonly used methods were using medicinal herbs and nutrition counseling in order to choose the right type of food and the way of cooking it. In contrast, homeopathy is less frequently used, and anthroposophy and naturopathic medicines were not used at all. The use of medicinal herbs is a common practice with a background of thousands of years, which has been mentioned in numerous domestic and foreign studies (33-36). The problem is that most patients think herbal medicines are harmless and have no complications (23). However, some herbs interact with the effects of chemotherapy drugs, some cause radiotherapy-induced skin reactions, leading to dangerous fluctuation in blood pressure, or interacting with anesthetic drugs during surgery (37).

The use of complementary medicine is dependent on different factors such as the place of residence, religious and cultural preferences, the patient’s initial complain the stage of cancer, and the physician’s approval regarding the method of using complementary medicine. Generally, in advanced stages, relaxation and spiritual therapies are the commonly used methods of complementary medicine, while homeopathy and acupuncture are mostly selected by the patients, who have recently been diagnosed with cancer (3, 36, 38).

The findings of the current present study showed that more than half of the patients under the study had no doubt about using this method, and often believed that they would accept and use complementary medicine, if it is introduced as a part of cancer treatment services. Nowadays, the tendency to accept complementary medicine therapies by cancer patients is increasing worldwide, from developed countries to third world countries (39, 40). The results of a systematic review showed that the perceptions of the users of complementary therapies suggest that these practices are beneficial. However, in one study, more than half of the patients regarded complementary medicine as useless (3) and in a study carried out by Fasching et al., 44.9% of the patients using complementary medicine had experienced complications (41). The reason behind this difference may be the fact that since complementary medicine is often used simultaneously with conventional medical treatments, in many cases, it is difficult to identify the positive or negative effects of it and to distinguish the results of these methods from one another (42). In addition, the desire to choose complementary medicine can be influenced by the time of cancer diagnosis; the more time passed since the disease is diagnosed, the more the patient’s willingness will be to use complementary therapies. Additionally, accepting complementary treatments may be the result of the need to overcome the unwanted complications of medical treatment or the desire to receive care that is more consistent with current natural processes. Over time, with changes in people’s beliefs on the definition of health, disease and medical care, patients’ tendency to use natural and healthy treatments may increase (43).

Despite patients’ preference and their interest in using complementary medicine, only one-fifth of cancer patients consulted with care providers, especially complementary medicine specialists, in order to use complementary medicine for cancer treatment. According to a study by Kremser et al., about two-thirds of women with breast cancer, and according to Wilkinson et al., 41% of men with prostate cancer consulted with their physician for the selection and use of complementary medicine (44). However, Richardson et al. found that more than half of the patients under study do not consult with anyone about using complementary medicine (45). Consistent with the latter findings, Shorofi and Arbon reported that patients do not usually talk to their physicians about complementary medicine and do not seek their opinions on using it (46). In this regard, it can be concluded that the most common reason for patients’ hiding the use of complementary medicine is the fear of its not being accepted by the care team. The other reason is that this type of treatment has not yet been documented by clinical trials. On the other hand, many nurses and doctors have not had any special training in the use of complementary medicine. Therefore, they often avoid talking with their patients about the use of complementary medicine for cancer treatment. Biological products can often influence biomedical activity and, thus, the health of individuals, and it is necessary that doctors be aware of all products used by their patients (7).

Regarding the cancer patients’ expectations of using complementary medicine, the findings showed that most of them expect to increase the general ability to resist the disease, improve daily performance, and reduce the complications of chemotherapy. They often seek to decrease the symptoms of anxiety, fatigue, depression, spiritual distress, and pain, problems with daily tasks, dyspnea, and weight change and sleep problems by using complementary treatments. Miller et al. believe that patients use complementary therapies for various reasons. In different studies, different expectations of using complementary medicine have been stated, such as physical health improvement and recovery (44, 47, 48), enhancing mental health (47-49), improving the quality of life (38, 47), decreasing the complications of conventional cancer treatments such as chemotherapy (47), increased physical and mental resistance, pain relief (50), mental relaxation (42), preventing weight loss, fatigue and emotional, and spiritual support. Overall, due to the lack of standard terminology and themes for identifying patients’ perceptions of their reasons for using complementary medicine, and the variety of their descriptions of it, it is difficult to interpret the patients’ goals in using complementary medicine; however, what all studies consider as the common goal is the improvement of general health and the general status of the disease (47). Thus, the integration of consulting services regarding the evidence-based use of complementary medicine, now regarded as integrative medicine, can be helpful and practical for oncology institutes that encounter diverse cultural populations and the high prevalence of traditional medicine use (6).

Since patients consider the use of complementary medicine as a traditional and non-scientific method, in many cases, they see it contrary to the care providers’ views; therefore, they may not express their real opinions. This can be considered as one of the limitations of the present research.

5.1. Conclusions

From the viewpoint of cancer patients, complementary medicine is an approach accepted as a complementary treatment method that can be effective in improving symptoms and enhance the quality of life in patients. Since complementary medicine is effective on all the physical and psychological symptoms of the patient, and given the fact that with the development of science and the ability of physicians to balance and coordinate the use of complementary medicine and modern medicine, the benefits of this type of treatment can be found in patients with cancer.

On the other hand, given the historical background of medicine in Iran, traditional beliefs dominate all aspects of life of individuals, and this is a turning point in the application of complementary medicine in the treatment of diseases, especially in cancer. On the other hand, due to the limitations of studies conducted on the effectiveness of some complementary medicine approaches, patients’ confronting the negative complications of these treatments is one of the concerns requiring more attention on the part of care providers. Given that in patient evaluation the use of complementary medicine is not taken into account by care providers, many patients do not know who can answer their questions. So, care providers’ awareness of this approach and addressing it is necessary while assessing the patient. On the other hand, this research merely focuses on patients’ opinions, while family and informal caregivers play a key role in treating the cancer patient. It is also suggested to examine their views in future researches. Considering the usefulness of both conventional medical treatments and complementary therapies, conceptualizing integrative medicine is essential.