1. Background

Colorectal cancer is one of the most frequent neoplastic diseases in human, ranked after lung and prostatic cancers in men and breast, lung, and cervical cancers in women (1). In developed countries, colorectal cancer (CRC), or rather its progression to metastatic disease, accounts for 25% of tumor deaths (2). CRC evolves through a series of morphologically recognizable stages, known as the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Currently, predicting patients’ prognosis is mainly based on the stage of CRC at the time of resection, histopathological grade of tumor, and changes in serum CEA levels (3, 4). However, clinical outcomes of patients with CRC is still difficult to predict; therefore, additional prognostic markers are required (3, 5, 6).

CD44 was, first, identified as cell surface hyaluronan receptor, but it is, now, known to be expressed in colonic mucosa and present in many physiologic and pathologic processes, including cell division, migration and adhesion, and survival (3, 7, 8). CD44 gene has almost 10 variable exons, leading to various patterns of splicing; that is how CD44 has multiple isoforms rather than its standard form (8). Some particular CD44 isoforms, including standard form (CD44s), V6, and V9 isoforms had a correlation with the depth of invasion, lymph node involvement, and overall survival in CRC (1, 3, 6, 9-15). However, some controversies could be observed in some studies with completely different results (7, 16-20).

The present study aims at investigating the expression of CD44s in primary CRC by immunohistochemistry (IHC) as well as exploring its relation with clinicopathological characteristics.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

A total of 102 patients were enrolled in this study. They had undergone surgical resection for primary colorectal adenocarcinoma at the department of surgery, Urmia Imam Khomeini hospital, Urmia, Iran between 2010 and 2012. Tumor staging was based on American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and Union lnrernational Contre le Cancer (UICC) systems (21). Tumors were histologically classified as well differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma according to WHO classification (22). The study is reviewed and approved by ethics committee of Urmia University of Medical Sciences. As the study was performed on paraffin blocks no written informed consent was obtained from any of the patients.

2.2. Tissue Specimens and Immunohistochemistry

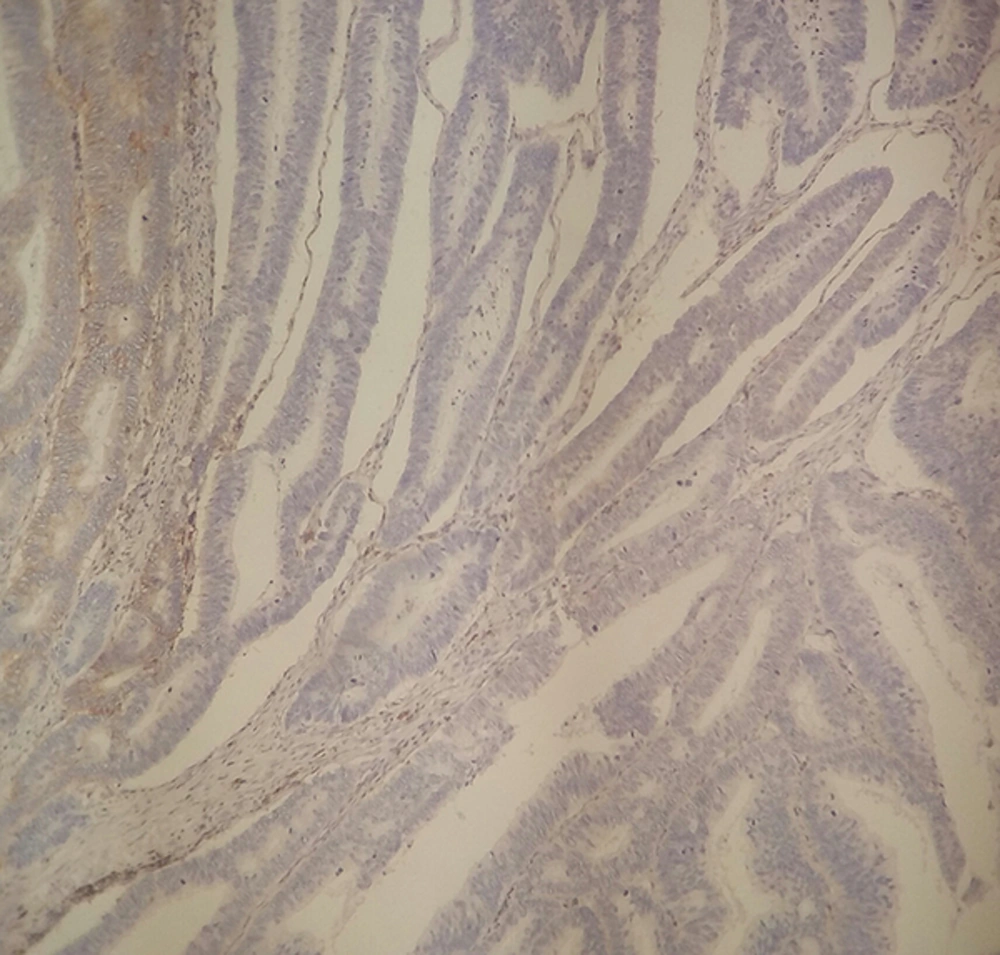

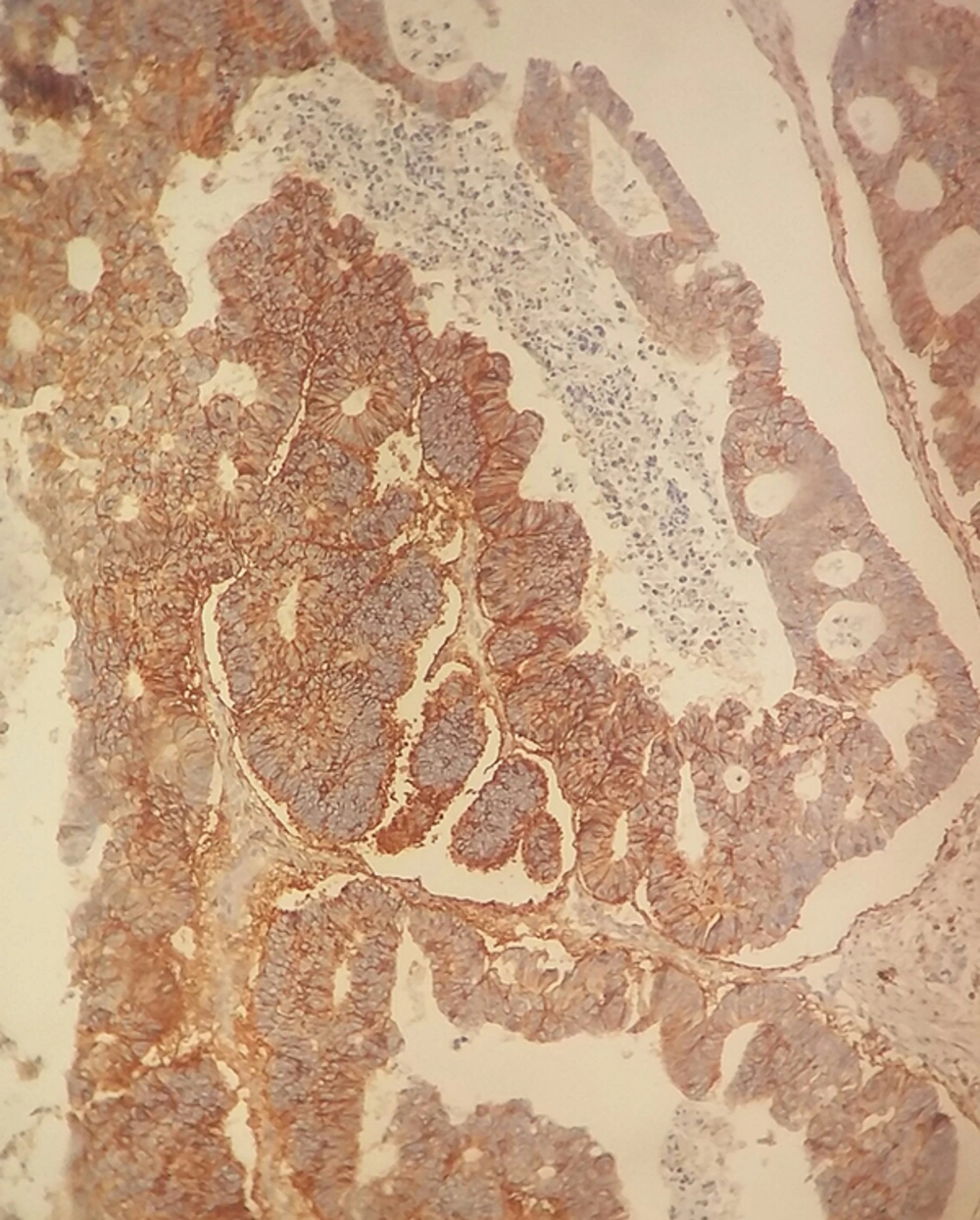

The non-necrotic portion of the tumors and surrounding normal mucosa were processed, using the standard paraffin wax technique after fixation in 10% formalin for 24 hours, and sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). From representative blocks of each case, 4 μm thick sections were obtained for IHC staining. IHC staining for CD44 was performed according to manufacturer’s protocol (clone DF 1485, DAKO Corporation, Glostrup, Denmark, mouse type). In brief, sections were deparaffinized in xylene for 30 minutes and rehydrated with graded alcohols and subjected to Tris-EDTA. After antigen retrieval, the slides were rinsed in TBS and incubated to quench endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 minutes. In order to reduce non-specific binding of antisera, sections were washed with TBS (15 minutes) before application of the primary anti-CD44 antibody (clone DF 1485, Dako Denmark, mouse type) for 1 hour in room temperature. Then, sections were rinsed in TBS again and were, subsequently, treated with envision-plus (DAKO Corporation, Glostrup, Denmark) for 30 minutes. The reactions were visualized with diaminobenzidine (DAB) as a chromogen. Finally, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Tumor cells with cytoplasmic or membranous staining pattern were regarded as positive. Staining less than 10% were defined as low/weak, 10% - 50% as moderate, and > 50% as strong/extensive expression. The staining of normal colonic mucosa, predominantly, in basal region of crypts was considered as internal positive control.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed, using SPSS version 16.0.1 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). The statistical differences between proportions were determined by χ2 analysis. Numerical data were evaluated, the using analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

3. Results

Among the patients, 57 were men and 45 were women with the mean age of 62.8 ± 15.67 years (29 - 100) and the mean tumor size of 5.61 ± 3.75 cm (1.5 - 30). IHC staining for CD44 demonstrated low expression level (< 10% of neoplastic cells) in 56%, moderate (10% - 50% of neoplastic cells) in 24%, and extensive in 20% of the cases (Figures 1 and 2).

The patients’ demographic data and relationship between CD44 expression and clinicopathologic parameters are shown in Table 1. No association was found between CD44 expression and tumor histology (P = 0.982), tumor stage (P = 0.695), gender (P = 0.054), tumor location (P = 0.830), lymphovascular invasion (P = 0.318), perineural invasion (P = 0.538), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.705), or tumor subtype (non-mucinous versus mucinous adenocarcinoma) (P = 0.510). The only association was found between CD44 expression level and patients’ age (p = 0.03). Twenty-five percent of tumors in patients younger than 60 years expressed CD44 expression strongly, whereas 16.1% of patients with 60 years or older had strong CD44 expression (Table 1).

| CD44 Expression level | Low | Moderate | Strong | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | I | 9 | 4 (44.4) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (22.2) | 0.695 |

| II | 55 | 29 (52.7) | 14 (25.4) | 12 (21.9) | ||

| III, IV | 38 | 25 (65.8) | 7 (18.4) | 6 (15.8) | ||

| Grade (Differentiation) | Well | 69 | 38 (55) | 17 (24.6) | 14 (20.2) | 0.982 |

| Moderate | 26 | 15 (57.7) | 6 (23.1) | 5 (19.2) | ||

| Poor | 7 | 5 (71.4) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (14.3) | ||

| Age | < 60 | 45 | 29 (64.4) | 5 (11.1) | 11 (24.5) | 0.03a |

| ≥ 60 | 57 | 29 (50.8) | 19 (33.3) | 9 (15.9) | ||

| Gender | Male | 57 | 34 (59.6) | 14 (24.5) | 9 (15.9) | 0.054 |

| Female | 45 | 24 (53.3) | 10 (22.3) | 11 (24.4) | ||

| Tumor location | Colon | 81 | 44 (54.3) | 20 (24.7) | 17 (21) | 0.83 |

| Rectum | 21 | 13 (61.9) | 5 (23.8) | 3 (14.3) | ||

| Vascular invasion | NO | 56 | 30 (53.5) | 12 (21.4) | 14 (25.1) | 0.318 |

| YES | 46 | 28 (60.8) | 12 (26.2) | 6 (13) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | NO | 67 | 36 (53.7) | 17 (25.3) | 14 (21) | 0.705 |

| YES | 35 | 22 (62.8) | 7 (20.1) | 6 (17.1) | ||

| Tumor size, cm | < 5 | 50 | 29 (58) | 13 (26) | 8 (16) | 0.629 |

| ≥ 5 | 52 | 29 (55.7) | 11 (21.2) | 12 (23.1) |

aSignificant.

4. Discussion

CD44 complex forms a family of cell surface adhesion molecules, which are involved in cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions, lymphocyte activation and homing, cell motility, differentiation, and migration (8, 23). The multiple protein isoforms are encoded by alternative splicing of a single gene and are, further, modified by a range of post-translational modifications.

In the present study, we used immunohistochemical staining against CD44s (standard) isoform. In this study, it was shown that CD44s expression was not correlated with clinicopathological characteristics of CRC, including tumor grade, the depth of invasion, and vascular/perineural invasion. Although some studies have reported that the decreased CD44 expression is an independent predictor of nodal metastasis (7, 17), no association, in this study, was observed between CD44 expression and nodal metastasis.

In contrast, Zavrides et al. reported that CD44 expression was associated with pathologic stage, histologic grade, and tumor location (1).

Asao et al. demonstrated that CD44 expression had decreased regional lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancers. They explained that this suppression activity may be due to CD44 binding to extracellular matrix in the sub-mucosal layer, immobilizing cancer cells, and preventing their spread (18).

In the same vein, Huh et al. reported that CD44 overexpression was correlated with the depth of invasion, lymphocyte involvement, and it may be an independent unfavorable prognostic factor for overall survival in advanced CRC, especially in stage IV (9).

Thus, there are still controversies on the definite role of CD44 and its isoforms in cancer development and progression. These discrepancies may be due to different patient material and follow up duration, antibodies, and immunohistochemical techniques used in different studies (2, 9).

Furthermore, a number of studies have demonstrated CD44 expression in most non-tumoral epithelial tissues, including stomach mucous membrane, small intestinal, prostate, ductal epithelium of breast, skin, hair follicles, and transitional epithelium (1, 2, 9). Likewise, CD44 expression is found in normal colonic crypt epithelium, predominantly in basal region of crypts, and benign neoplastic tissues, such as adenomatous polyps (16, 24, 25). Such results argue the role of CD44 as an indicator of cancerous process.

Herlich et al. reported that CD44 could act as both tumor promoter and tumor suppressor molecule, depending on its site of action in cancerous cells. This interesting finding would be another explanation for discrepancies and controversies in the literature about the role of CD44 in cancer (26).

CD44 can cause complexities with various molecules, including some growth factors such as EGFR receptors and HER2 as well as activating them; through this mechanism, CD44 can act as a tumor promoter molecule. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is another growth factor (GF), which can be modulated by CD44 and is one of the important GFs involved in colorectal cancer development (8). P53, TGF-b, and matrix metaloproteinases (MMPs) are other growth factors that can be modulated by CD44 and can be involved in CD44 induced tumorigenesis (8). Other studies have reported tumor suppressing activity of CD44 (27). It has been explained that dual activity of CD44 is related to its molecular weight, in which high molecular weight CD44 variants are tumor suppressors, and low molecular weights may act as tumor promoters (8).

Totally, no relation was found between CD44s expression and any tumoral characteristics of colorectal cancer. Considering the controversies in CD44 mechanism of action, further studies are suggested in different variants of this molecule so as to make its role more understandable in colon cancers.