1. Introduction

The spleen is infrequently involved in neoplastic processes. Primary benign splenic tumors include lymphangioma, hemangioma, littoral cell angioma and splenic cyst, and solid lesions such as inflammatory pseudotumor and hamartoma. Lymphoma and angiosarcoma are primary malignant neoplasms affecting the spleen (1, 2). Primary splenic lymphoma (PSL), which is usually of non-Hodgkin B-cell origin, comprises less than 1% of all lymphomas (2, 3). Due to rarity and unspecified presentations such as fever, malaise, weight loss, lower upper quadrant pain, or discomfort due to the enlarged spleen (4, 5), the diagnosis of splenic lymphoma is often hindered (5), which can potentially influence its prognosis. The physicians must be aware of clinical and imaging features of malignant as well as benign splenic pathologies to be able to differentiate them when encountered symptomatically or incidentally (6).

2. Case Presentation

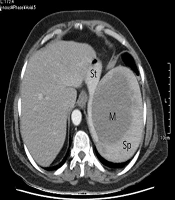

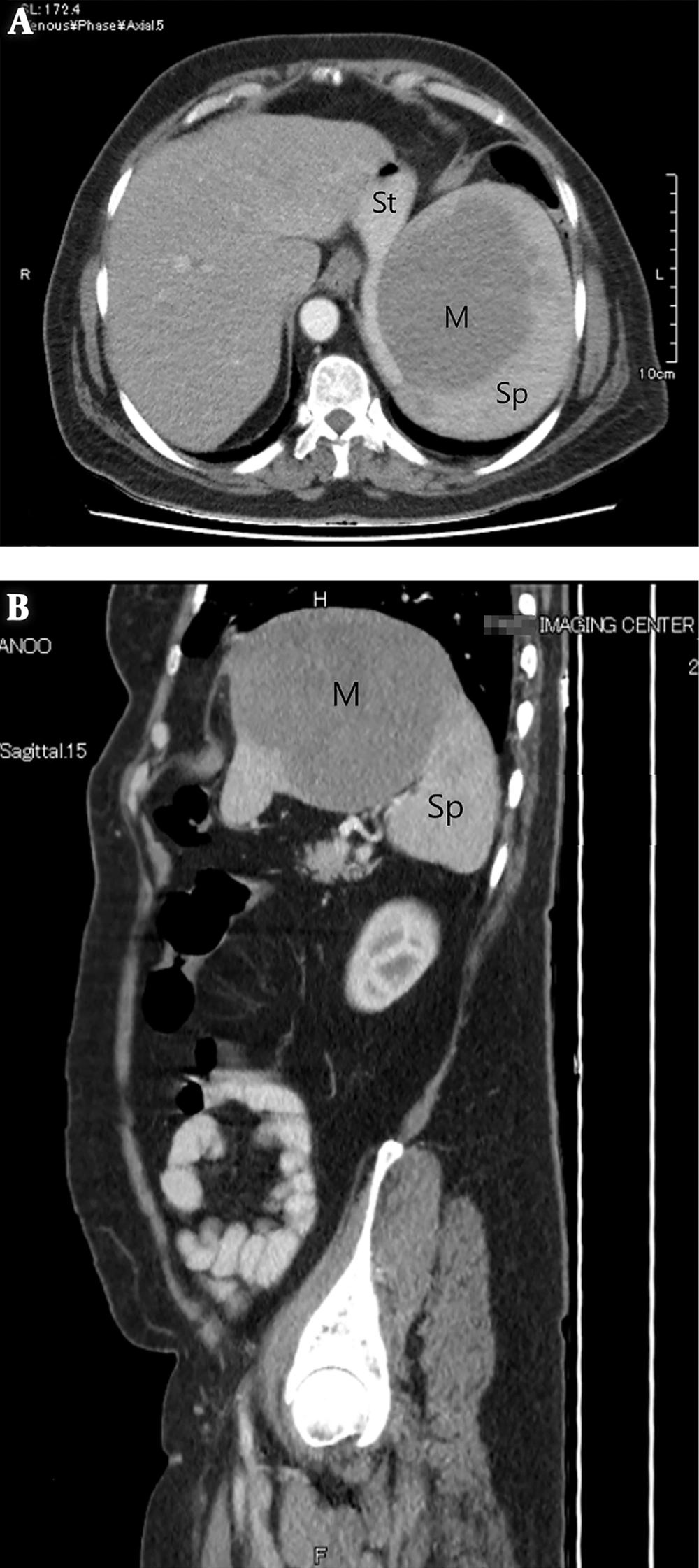

A 63-year-old female with a 1-month history of abdominal pain presented to our emergency department. The pain was more intense in the left upper quadrant with a colicky pattern, which got worse after eating meals and was not positional. The patient complained of weakness, fatigue, fever, chills, and night sweats, as well as weight loss of about 5 kg in 1 month. She also reported constipation and mild dyspnea but did not experience nausea, vomiting, urinary symptoms, or jaundice. The medical history of the patient was clear and surgical history was positive for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. She denied any drug or substance abuse and the family history was negative. Physical examinations revealed the scar of cholecystectomy, mild left upper quadrant abdominal tenderness without rebound tenderness or muscle guarding, and splenomegaly. No lymphadenopathy was detected. The rest of the examination including rectal evaluations was unremarkable. Complete blood count (CBC) showed mild anemia (hemoglobin: 10.6 g/dL). Other laboratory blood tests were within normal ranges, except for an elevated alkaline phosphatase level (620 U/L). An abdominal ultrasound (US) was done, showing a huge hypoechoic mass in the superior aspect of the spleen, measuring 90 × 88 mm in size. Computed tomography (CT) scan displayed a hypodense mass partially exophytic from the superior aspect of the spleen, measuring approximately 124 × 94 × 104 mm in size (Figure 1). No lymphadenopathy was identified in the abdominal and pelvic region. The patient underwent a midline laparotomy and splenectomy and the spleen (Figure 2) was sent for histopathological examination, which revealed a high-grade B-cell lymphoma measuring 17 × 16 × 10 cm in size with capsular invasion without lymphovascular invasion. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was referred to an oncologist to complete the treatment process.

3. Discussion

Primary neoplasms of the spleen can be divided into vascular neoplasms originating from the red pulp, and lymphoid neoplasms arising from the white pulp. Hemangioma, lymphangioma, and hamartoma are among primary vascular neoplasms of the spleen (2). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is the most common hematological malignancy of the spleen, with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma being the most common type. About 30% to 40% of NHL and one-third of all Hodgkin’s lymphoma involve the spleen at presentation (7). PSL is characterized as limited involvement of the spleen and immediately nearby lymph nodes, whereas the secondary type, which is more common, is defined as lymphomatous involvement of the spleen, as well as the nodes, other than splenic hilar ones (8).

Diagnosing PSL can be challenging since it often has nonspecific manifestations and can even present with complications such as splenic rupture and hypersplenism (3, 4). In a retrospective study conducted by Bairey et al. (9) on 87 patients diagnosed with primary splenic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the patients had a mean age of 59.6 years and 57.5% were male; 97% of them presented with splenic masses, 84% with elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels, 84% with splenomegaly, 81% with abdominal pain, and 59% with B symptoms. In 39 patients, splenectomy and in 46 patients, core-needle biopsy led to the diagnosis. They also came to the conclusion that splenectomy at diagnosis can improve survival, particularly at an early stage. Chen et al. (10) analyzed 53 cases of splenic lymphoid and hematopoietic tissue tumors and concluded that splenectomy can yield a partial or complete improvement of blood counts. According to a study carried out by Djokic et al. (11) splenomegaly accompanied by malaise and weight loss should raise suspicion for underlying neoplastic condition, as seen in our patient, and would require further diagnostic approaches.

A number of splenic lymphoma cases have been reported in the literature: Kattepur et al. (12) presented a 50-year-old female patient without comorbidities, who presented with left upper quadrant abdominal pain since 2 months and a scenario similar to that of our patient’s. Ingle and Ingle (13) reported a female patient with abdominal pain and weight loss without fever or lymphadenopathy. Other than being febrile, our patient shared similar symptoms to those experienced by the 41-year-old patient. Khalid et al. (14) described a 68-year-old male patient with left-sided abdominal pain, massive splenomegaly, and thrombocytopenia.

Navarro et al. (15) reported a 69-year-old female patient with abdominal pain and large splenomegaly diagnosed with splenic lymphoma, who unfortunately died due to septic shock 4 months after diagnosis.

3.1. Conclusions

Rarity and the unspecified presentation should not cause physicians to dismiss splenic lymphoma from the differential diagnoses. When diagnosed at an early stage, PSL can carry a better prognosis and be managed more prosperously.