1. Background

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy of women around the world that has more severe mental and emotional effects than other types (1). Despite recent improvements in pharmacological treatment, pain experience is still the most important problem affecting patients’ lifestyle (2), and the complete relief of pain is rare (3).

Recently in pain studies, it is suggested to use a biopsychosocial (4) somatic, cognitive, emotional, behavioral, social, and motivational (SCEBSM) model. The cognitive factor in this model means cognitive patterns in perception and making sense of pain. The most important cognitive patterns are catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and time perspective (5).

Pain catastrophizing is the tendency to negative thought style in response to pain, which is characterized by exaggerating the minatory meaning of pain (6) and a cognitive pattern that individuals show to focus on cognitive threatening cues to making sense of their pain. This cognitive pattern amplifies the negative value of pain and decreased ability to control pain (7).

Social psychology suggests that we have a basic abomination to injustice and belief in just world: “individuals need to believe they live in a world, in which each person gets what he deserves and deserves what he gets, whether good or bad” (8). Health psychology research suggests that individuals’ beliefs in justice can affect their health outcomes (9). Perceived injustice in health and illness has been operationally defined as: “a cognitive appraisal comprising elements of the exaggerated severity of loss consequent to injury or pain onset, perceived irreparability of loss, a sense of unfairness, and blame” (10). Research has shown that some psychological factors such as depression (11-13), anxiety (12), psychological distress (14), and personality traits like the lack of self-esteem (15), pessimism (16), neuroticism (15), and external locus of control (15), as well as social factors like social disability (17), decrease income (11, 18), and even social class (18) can lead to the perceptions of injustice in patients.

Time perspective shows the individual’s method regarding psychological notions of past, present, and future (19). It was defined as a stable unconscious process determined by circumstances, through which the personal and social experiences are allocated to time frames. These frames have significant impacts on individuals’ cognitions and actions. The impact of the time perspective on psychological well-being (20), subjective well-being (21), anxiety (22), and depression (23) has been broadly investigated. The findings of time perspective in a patient with cancer indicate that past negative and present-fatalistic scores have a high relationship with distress, depression, anxiety, and aggression in these patients (24). Another research found that scores of future and past-positive are more than others (25). Other studies showed past-negative is related to depression (26). Also, present fatalists are negatively and the future is positively related to physical activity in the patient with cancer (27).

As was previously mentioned, the most important cognitive patterns are catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and time perspective (5). The association of these variables has been studied in previous studies. Studies have shown past-negative is correlated with pain catastrophizing (28). More recently researchers have found that all factors of pain catastrophizing (rumination, helplessness, and magnification) have positive correlations with the past-negative (29). On the other hand, it has been made clear that pain catastrophizing has a positive correlation with the perceived injustice (30). It is indicated that catastrophizing mediates the relationship between personal belief in a just world and pain outcomes in chronic pain (9).

Theoretical explanation as to why pain catastrophizing correlated with perceived injustice and past time perspective relates to two psychological models. The first one is the attention bias model (31). In this model, past negative and injustice beliefs are considered a dysfunctional bias of attention toward negative events. This model addresses why and how maladaptive attention interrupted to a state of cognitive and behavioral immobilization (31).

The second model is the schema-activation model of Sullivan et al. (6, 32) that proposed that past negative and injustice beliefs possess special schema, which consisted of a distorted cognition with excessively pessimistic beliefs about negative experiences and actual ability to cope (33).

Despite acknowledging these results, still, two points have remained. First, although the relationship between time perspective and perceived injustice with pain catastrophizing has been investigated and the relationship of these 3 variables with each other has not yet been studied. Second, most of the research has not focused on cancer.

2. Objectives

Therefore, considering these points led us to two hypotheses: (1) Pain catastrophizing would be correlated with the perceived injustice and past time perspective; (2) the perceived injustice and past time perspective can predict pain catastrophizing in women with breast cancer.

3. Methods

The present study was descriptive-correlational in terms of method. The statistical population consisted of all women aged 20 to 50 years with a breast cancer diagnosis in 5 hospitals in Tehran, Iran (Emam Khomeini, Hazraterasol, Mohebmehr, Shahram, and Khatam). The number of patients with breast cancer in these hospitals was 219, which required at least 140 samples were selected according to the Krejcie and Morgan So, So, 142 voluntary female subjects were selected through the available sampling method between March and April 2019.

In each hospital, patients with breast cancer, who met the inclusion criteria, were initially identified. Then, the research method and how to use the results based on ethical considerations were explained verbally. The written informed consent was taken from all participants and the Payame Noor University board of ethics approved the protocol of the study. If they agreed, they would complete questionnaires in the presence of the researcher. This was done by frequent visits to these 5 hospitals.

The inclusion criteria included the diagnosis of breast cancer by specialists at least 6 months and the utmost 1 year before the onset of the study, getting chemotherapy, age between 20 and 50 years, at least educated as diploma, and consent to participate in the research. Ethical issues including informed consent, right to withdraw from research, confidentiality, respect for privacy, considering plagiarism, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, and redundancy have been completely observed by the author. After selecting the sample, the questionnaires were completed by the participants with the supervision of the researcher. Then results were analyzed through the regression and path analysis method by SPSS-19 and AMOS-22.

3.1. Measures

3.1.1. Injustice Experiences Questionnaire

The Injustice Experiences questionnaire is a 12-item test that assesses pain-related perceptions of injustice (17). These pain-related items evaluate two correlated factors: severity/irreparability of loss and blame/unfairness. Each one is measured by a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (all the time). The Injustice Experiences questionnaire has high internal and test-retest reliability and it is valid among English, French, and Persian-speaking individuals (17, 34). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82 in the present study.

3.1.2. Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory

The Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory is a 36-item scale developed to evaluate different focused of time perspective (22). It assesses 5 components of time perspective. Items are only related to the past (past positive 7 items and past negative 9 items). Each dimension is measured by a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (absolutely untrue) to 5 (absolutely true). Studies provided support for the internal consistency, stability, and structural validity of this scale (35). Cronbach’s alpha of past positive and past negative were 0.78 and 0.83, respectively, in the present study.

3.1.3. Pain Catastrophizing

The Pain Catastrophizing scale is a 13-item measure that was developed and validated by Sullivan et al. (32). These items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 6 (always). This test is a reliable and valid measure and a high internal consistency (11). Also, it has suitable reliability and validity in the Iranian population (36). Cronbach's alpha was 0.86 in the present study.

4. Results

First of all, the characteristics of the samples are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Age | 42.18 ± 7.64 |

| Married | 82 (58) |

| Time of diagnosis, mo | 10.03 ± 0.08 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

The mean and standard deviation ± SD of participants’ scores of research variables are shown in Table 2.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| PI | 25.72 ± 10.7 |

| PN | 27.16 ± 5.7 |

| PP | 21.49 ± 4.3 |

| PC | 3.82 ± 0.46 |

Abbreviations: PC, pain catastrophizing; PN, past negative; PP, past positive; PI, perceived injustice.

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

For analyzing the correlation among all variables, the Pearson test was used. These results are illustrated in Table 3.

In line with results shown in Table 3, PC is significantly correlated with PI, PN, and PP. Also, there is a significant correlation between PI and PN.

A step by step regression analysis was used to test whether past time perspective and perceived injustice were associated with pain catastrophizing. The results are illustrated in Table 4.

According to Table 4, both models in the first and second steps are significantly meaningful, and the second model can explain more total changes of PC in comparison with the first one (72% is more than 67%).

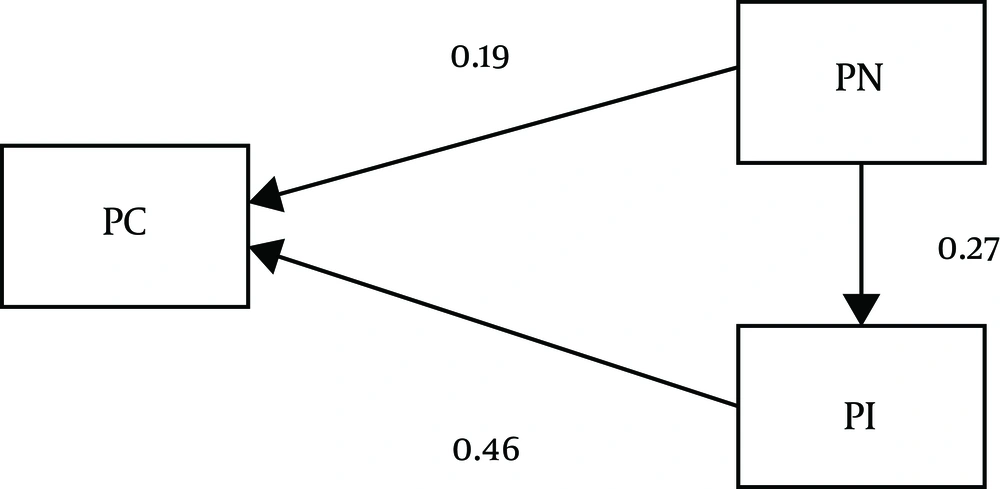

Also, in the first step, only PN entered into the equation and PN and PI entered into the equation in the next step. The β of IP is 0.46 that means IP can predict 46% of PC. The β of PN in the first step is 0.31 and decreases in the next step to 0.19 that means although PN can predict PC directly, PI is a mediator variable between PN and PC.

The strength of direct and indirect links between variables is indicated by the path analysis. These results are in Table 5 and Figure 1.

| Link | Regression Coefficient | P |

|---|---|---|

| PI → PC | 0.46 | 0.001 (Direct) |

| PN → PC | 0.19 | 0.01 (Direct) |

| PN → PI → PC | 0.27 | 0.001 (Indirect) |

5. Discussion

As was previously mentioned, in the SCEBSM model of pain study, different biopsychosocial factors are involved and the most important cognitive factors are catastrophizing, perceived injustice, and time perspective. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between these cognitive patterns and whether perceived injustice and past time perspectives are correlated with pain catastrophizing and could predict it.

The findings indicated a significant correlation between pain catastrophizing with past positive (negatively) and past negative (positively) and perceived injustice. These results are similar to other studies that showed past-negative and past-positive correlated with pain catastrophizing (5, 28, 29). Likewise, the results are consistent and comparable with findings in previous investigations concerning the relationship between pain catastrophizing and perceived injustice (9, 30). But, the difference is that they are not about breast cancer and were conducted generally on pain or chronic pain.

Another important finding from the regression and path analysis indicated that past negative can predict pain catastrophizing both directly and indirectly through mediating perceived injustice.

The same theoretical models will be used to describe these results. Based on the attention bias model (31) and schema-activation model (6, 32), past negative and injustice beliefs create a dysfunctional bias of attention toward negative events.

If these variables are studied in a SCEBSM model, it should be considered that cognitive functions cause to develop an autobiographical and episodic memory, self-related processing, and future imagine (32). This means that negative events shape negative memories and eventually lead to a dominant cognitive pattern for information processing. This cognitive pattern is a negative time perspective. When the prevailing perspective to the past is negative, these negative memories form an active negative schema, in which events are perceived.

The negative time perspective means focusing on events that are very powerful because they dominate all the past. Secondly, their effect remains until now because the individual could not overcome them and they were uncontrollable (32).

Under the influence of this schema, the experience of pain is considered a negative experience, just like other negative memories in the past. So, the characteristics of those memories are also attributed to this current pain experience. Thus, the experience of pain will be perceived in this pattern and processed as a ruminate, helpless, and magnificent event. In other words, it will lead to pain catastrophizing (33).

On the other hand, it is important to note that one of the most important components of cognitive processing is attention. There are many stimuli around at any given moment, but only some of them are considered. When negative memories are dominant cognitive patterns, they cause salience and attention bias to negative. This attention bias leads to perceiving more negative events. Life will be filled with negative experiences. This leads to a sense of injustice. One has to ask why all of my life experiences are negative and frustrating. As a result, the negative past perspective leads to a perception of injustice (31).

Injustice perception of pain has different dimensions. One of them is the disability. In an injustice world, pain is the result of injustice destiny. Not only the individuals have no role in causing pain, but also they cannot control it. Besides, instead of using pain management and coping techniques, some reactions like anger, revenge, and blame are used. These negative reactions increase negative emotions such as depression and frustration, and they are associated with more perception of pain intensity and severity. Therefore, more perceived pain severity and inability will lead to pain catastrophizing (33).

5.1. Conclusions

Overall, the present study showed a significant positive correlation between pain catastrophizing with perceived injustice and past negative and negatively with past positive. Also, the results of the current study indicated that perceived injustice and past negative time perspective can predict pain catastrophizing.

5.2. Limitations

The present study has some limitations. First, the participants of this research were volunteers and chosen from some hospitals in Tehran; thus, they may not be representative of the target population. Besides, the patients, who accepted to participate, have a different type of socio-economic status. Therefore, the influence of social status type should be considered. The third limitation is about the relationship between pain intensity and research variables that were not investigated. Also, due to the exploratory nature of the study, we could not ascertain the mechanism, through which perceived injustice and past negative time perspectives influenced catastrophizing in patients with breast cancer.

These limitations suggest that future research should address these issues by a qualitative study or by using mixed methods. We also hope that the results of this study will lead to the development of interventions aimed at controlling and balancing negative time perspective and injustice pain experiences to reduce pain disaster.