1. Background

Social-virtual addictions have recently become a major concern and a common problem worldwide. The use of social networking sites (SNS), such as Telegram, Instagram, WhatsApp, YouTube, and other SNS, has dramatically changed the way people socialize, share information, work, perceive others, and present themselves (1). Moreover, SNS addiction has been introduced as a new behavioral addiction, along with increasing social network sites (2). Addiction to SNS is defined as a considerable concern for social networks, great interest in using social networks, spending much time and effort on social networks so that it harms other social, occupational, and academic activities, interpersonal relationships, or psychological well-being and health. In addition, SNS addiction is experienced as a subjective feeling of lack of control in which the person uses social networks highly despite the negative effects of using social networks and attempts to change or control them (3).

Theoretical and empirical models discuss that dispositional and sociocultural factors and behavioral promotions are effective in addition to SNS (4). The attachment theory considers the character differences in the performance of the attachment system and mediates the close relationships (including relationships with parents and romantic ones) as a behavioral regulator system, reflects character-based cognitions and emotions of individuals, and anticipates different methods to make interaction with friends and strangers. Empirical evidence supports the mediating role of attachment in using SNS and indicates that attachment style participates in the conceptual integration of SNS with personality traits (5).

Furthermore, previous research showed that personality traits stand out as one of the most important factors for understanding social-virtual addictions (6). Researchers have shown that social networks can form and reflect our characters (7). Personality traits are stable characteristics that are not readily changeable; they are stable and durable response tendencies toward different stimulants in the same way and can predict the behavior of a person in various situations (8). These traits may make the person vulnerable to some disorders. Personality traits have been investigated using the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI), which is based on Cloninger’s theory. The TCI is a battery of tests designed to assess differences between people based on seven basic dimensions of temperament and character (9).

Seemingly, previous studies on emerging virtual addictions have focused on internet and online gaming addiction without sufficient attention to social networking. Moreover, former studies that examined the relationship between virtual addiction and personality traits usually used the five-factor NEO Personality Inventory. However, Cloninger’s Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI) seems to be a more suitable instrument to test social network addiction because this inventory includes both temperament and character dimensions. Moreover, the main weakness in studies on social network addiction is a lack of a clinical instrument to assess social network addiction, in particular in Iranian studies that do not have a proper clinical tool. Hence, this study aimed to fill this gap by using the “Social Media Disorder scale”, which is designed based on the diagnostic criteria of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) (10). Such studies can provide suitable and evidence-based theoretical and therapeutic frameworks for such disorders by expanding the relevant knowledge range. The wide use of and interest in social media, as well as spreading development of them, make it essential to examine the specifications of users and identify antecedents of social network addiction. It will be possible to design proper interventions and prevent such addiction if factors affecting the excessive use of social networks are identified.

2. Objectives

According to the mentioned points, this study aimed at examining the association between attachment style of individuals and social network addiction with the mediating role of personality traits.

3. Patients and Methods

The statistical population of this study includes all of the students who were studying at universities in Tehran, including universities of the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Science such as governmental, Azad, Payam Noor, and non-profit universities. The inclusion criteria for participants were (A) being a student in universities located in Tehran; (B) informed consent to participate in research. The exclusion criteria were (A) not answering demographic questions or at least one of the scales; (B) the lack of verbal agreement to participate in the research. Participants were selected using the convenient sampling method. To calculate the sample size, the below formula was used (11):

Sample size = (number of paths + number of factor loads + number of errors) × 5

The path in the causal model represents the effect of one variable on another. Factor load is a numerical value that determines the intensity of the relationship between a hidden variable and the corresponding explicit variable during the path analysis process. Error indicates the amount of variance of the endogenous variable that is explained by the variables affecting it.

The sample size was calculated at 220 individuals. Thus 300 questionnaires were distributed among students, and 261 questionnaires were gathered due to the removal of 20 uncompleted questionnaires. Although we asked the participants to return the questionnaires and we did the follow-ups, 39 questionnaires were lost, and also 20 questionnaires were so incomplete that they could not be used even by using imputation methods. Finally, 241 questionnaires (91 boys and 150 girls) were inserted into the software to be analyzed statistically. Measurement instruments were as follows:

A) Measurement of Attachment Qualities (MAQ): Carver (1997) designed this questionnaire to measure four items of attachment. This measure consists of 14 items that their responses are scored based on a 4-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) (12). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of Carver’s study (1997) was 0.85, 0.68, 0.71, and 0.69 for secure, avoidant, worry-ambivalent, and disorganize-ambivalent attachment styles, respectively. The Persian version of this questionnaire has been normalized for Iranian society by Isanejad et al. (13). They obtained Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.76, 0.81, 0.83, and 0.85, respectively.

B) Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS): This scale was designed by Regina van den Eijnden, Jeroen Lemmens, and Patti Valkenburg in 2017. This instrument was designed based on the DSM-5 factors for Internet gaming disorder. The long-form of this scale consists of 27 items. Three items have been allocated to nine criteria. These criteria measured by this scale are preoccupation, tolerance, withdrawal, displacement, escape, problems, deception, displacement, and conflict. High reliability of this scale has been reported by designers (Cronbach’s alpha, 0.81) (10). A preliminary study of normalization of this scale on Iranian students led to the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.88.

C) Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): This inventory consists of 125 items, that respondent responds to true-false answers. TCI includes four scales related to temperament (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence) and three scales associated with a character (cooperativeness, self-directedness, and self-transcendence). This test was used for the first time in Iran by Kaviani and Poornaseh (14), who obtained reliability coefficients of 0.96, 0.91, 0.61, 0.76, 0.95, 0.85, and 0.88, respectively.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 25 and LISREL version 8.80 software. In addition, chi-square, correlation, and path analysis tests were used.

4. Results

Table 1 demonstrates the descriptive analysis of data.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 91 (37.8) |

| Female | 150 (62.2) |

| Academic Degree | |

| BA | 167 (69.3) |

| MA | 62 (25.7) |

| PhD | 12 (5) |

| Age | |

| 18 - 25 | 170 (70.5) |

| 26 - 33 | 62 (25.7) |

| 34 - 45 | 9 (3.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 220 (91.3) |

| Married | 21 (8.7) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 72 (29.9) |

| Unemployed | 169 (70.1) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

Table 2 indicates the number of members in the social network, spending hours, and membership of respondents in each one of the social networks.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Membership | |

| Yes | 241 (100.0) |

| No | 0 (0) |

| Hours | |

| Lower than one | 19 (7.9) |

| 1 - 2 | 56 (23.2) |

| 2 - 3 | 18 (7.5) |

| 3 - 4 | 83 (34.4) |

| 4 - 5 | 32 (13.3) |

| > 5 | 33 (13.7) |

| Social network | |

| Telegram | 219 (90.8) |

| 190 (78.8) | |

| 169 (70.1) | |

| Tweeter, Facebook, YouTube and others | 138 (57.2) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

Research hypotheses are tested herein. The first hypothesis indicates that there is a significant statistical relationship between attachment styles and social network addiction. The results showed there is a positive and significant relationship between worry-ambivalent (r = 0.308, P < 0.05) and disorganize-ambivalent (r = 0.322, P < 0.05) attachment styles and social network addiction; while there was no significant correlation between secure (r = 0.021, P < 0.05) and avoidant (r = 0.077, P < 0.05) attachment styles and social network addiction.

The second hypothesis pointed to a statistically significant relationship between attachment styles and personality traits. According to Table 3, a general relationship was confirmed between attachment styles and personality.

| Variable | Novelty Seeking | Harm Avoidance | Reward Dependence | Persistence | Cooperativeness | Self-Directedness | Self-Transcendence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | 0.114 | -0.153a | 0.236b | -0.058 | 0.248b | 0.078 | 0.041 |

| Avoidant | -0.213b | 0.275b | -0.374b | -0.037 | -0.243b | -0.141a | -0.112 |

| Worry-ambivalent | 0.174b | 0.423b | 0.344b | -0.157a | 0.011 | -0.433b | 0.054 |

| Disorganize-ambivalent | 0.140a | 0.328b | 0.007 | -0.102 | -0.175b | -0.451b | 0.046 |

aCorrelation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

bCorrelation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The third hypothesis assumed a statistically significant correlation between social network addiction and personality traits. The results showed there is a positive and significant correlation between social network addiction and personality traits of novelty seeking (r = 0.245, P < 0.05), harm avoidance (r = 0.156, P < 0.01), and self-transcendence (r = 0.217, P < 0.05), while there was a negative and significant relationship between social network addiction and personality traits of persistence (r = -0.216, P < 0.05), cooperativeness (r = -0.208, P < 0.05), and self-directedness (r = -0.414, P < 0.05). There was no significant correlation between social network addiction and the personality trait of reward dependence.

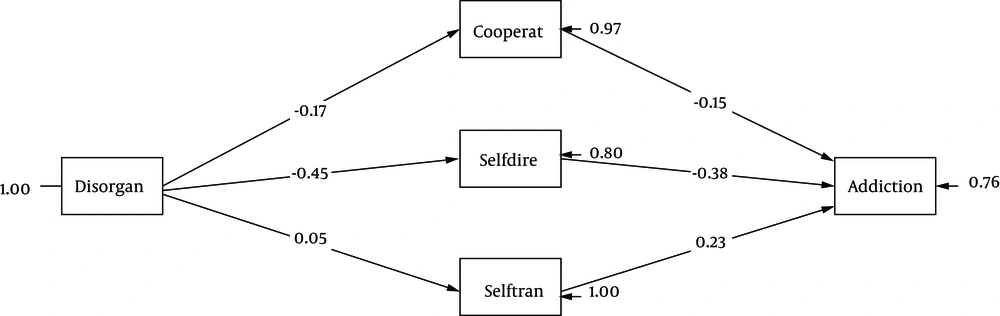

The final and fourth hypothesis assumes that personality traits play the mediating role in the relationship between attachment styles and social network addiction.

Moreover, comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), and normed fit index (NFI) indicators obtained scores greater than 0.9, NNFI indicators obtained a score close to 0.9, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) obtained the score lower than 0.1, χ2/df indicator obtained 3.13. According to the scores calculated for the mentioned indicators in the hypothetical model, the mediating role of personality traits in the relationship between attachment style and social network addiction had a relatively good fit.

Considering the multivariate nature of the fourth hypothesis, the path analysis method was used in hypothesis testing to examine the mediating role of personality traits. First, standardized coefficients of direct effect, indirect effect, total effect, and multiple correlations between variables are examined then five indicators of Chi-square to degrees of freedom (χ2/df), comparative fit index (CFI), the goodness of fit index (GFI), the normalized fit indicator (NFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were evaluated. The model of equations suggests that χ2/df lower than 3, RMSEA coefficient lower than 0.08, and fit indicators GFI, CFI, NFI with rates close to 0.95 are acceptable fit indicators of the structural equation model.

The obtained indicators from Table 4 shows that the fit model was appropriate. The results obtained from the first hypothesis showed there is a positive and significant relationship between disorganize-ambivalent (r = 0.322, P < 0.05) attachment style and social network addiction. The suggested model in this research indicates that character plays a mediating role in the relationship between social network addiction and disorganize-ambivalent attachment style (Figure 1). Among the character dimensions, self-directedness (SD) dimension has the most fitness between disorganize-ambivalent attachment style and social network addiction. The obtained results showing that among attachment styles, the disorganize-ambivalent attachment can mediate the social network addiction owing to its character dimension.

| Indices | χ2/df | CFI | IFI | NFI | NNFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scores | 3.13 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.09 |

5. Discussion

According to the first hypothesis, this study established the relationship between social network addiction and attachment styles, considering the theoretical links between these variables. There was no significant association between secure attachment style and social network addiction, which was in line with findings obtained by previous studies (15). People with secure attachment style and high self-esteem that like intimate relationships and share their feelings with others (16) are exposed to a lower risk of social network addiction. In line with previous studies, this study also did not find any significant association between social network addiction and avoidant attachment style (17, 18). Those who have avoidant attachment style, use fewer social networks, share less information in their profiles, and less likely to have a positive attitude toward social networks because they are autonomous, do not tend to share their feelings, and see other people as unreliable. There was a significant positive relationship between social network addiction and worry-ambivalent and disorganized-ambivalent attachment styles; this result indicates that these two dimensions of attachment style expose persons at the risk of social network addiction that is matched with results of previous studies (17, 19). People with ambivalent attachment styles fail to make a relationship with others, prefer loneliness and isolation, have more tendency toward social networks due to their insecure feeling, anxiety, and lack of self-confidence or trust in others.

The second hypothesis suggested a significant statistical relationship between attachment style and personality traits. This study found a positive relationship between secure attachment style and personality traits of reward dependence and cooperativeness as well as a negative correlation between secure attachment style and harm avoidance. This finding was in line with the results obtained from previous studies (20). In other studies that had used the NEO test to evaluate personality traits (21), a negative relationship was found between secure attachment style and neuroticism, while a positive relationship was found between secure attachment style and extraversion. It was also found that neuroticism positively correlates with harm avoidance, whereas negatively correlates with self-directedness (22). Furthermore, there was a positive relationship between extraversion and novelty seeking, reward dependence, cooperativeness, and self-transcendence, while there was a negative association between extraversion and harm avoidance. People with a high secure attachment style obtain a high agreeableness score (23), which is in line with the findings of the present paper because we found a positive relationship between agreeableness and cooperativeness (22).

The third hypothesis suggested a significant statistical correlation between social network addiction and personality traits. The obtained results showed a significant relationship between the temperament dimension of personality- except for reward dependence- and vulnerability to addiction. Previous studies have shown no difference between personality traits in drug and internet addiction (24). Similar to previous studies, a higher novelty-seeking in people, a higher vulnerability to anxiety and depression, sensation seeking, and positive attitude toward addiction. This finding was in line with the results of these studies (25, 26). Moreover, there was a negative and significant relationship between the temperament dimension of persistence and social network addiction, which is matched with previous studies results (27). Findings obtained from these studies have shown that lower persistence leads to a higher vulnerability of people to addiction. Therefore, it can be explained that preference for instant rewards, a tendency toward sensation-seeking, novelty-seeking, finding simple ways to achieve the reward, the lack of attempt, insisting on doing things, and short reaction time are components that expose a person to higher risk (28). The present study found a negative and significant association between social network addiction and character dimensions of cooperativeness and self-directedness, which was in line with previous researches (29, 30). It means people with higher score they in mentioned specifications, will have a lower probability of social network addiction. Addicted people indicate lower levels of self-directedness and cooperativeness. It can be explained that low levels of self-directedness and cooperativeness in these persons indicate the concept of escape and inhibition response based on the neurological approaches and this may expose drug users to at a higher risk of impulsivity and behavioral problems (31).

The final hypothesis argued whether personality traits could play a mediating role in the relationship between attachment style and social network addiction. The obtained results showed that among attachment styles, a disorganize-ambivalent attachment style could mediate the social network addiction owing to its character dimension of self-directedness. According to the findings of this study, there is a positive and significant relationship between disorganize-ambivalent attachment style and SNS addiction (0.322) (the first hypothesis), which shows that insecure attachment can predispose individuals to SNS addiction. On the other hand, there is a negative and significant relationship between the character dimension of self-directedness with the disorganize-ambivalent attachment style (-0.451) (the second hypothesis) and with SNS addiction (-0.208) (the third hypothesis), which shows self-directedness can be a protective factor against addiction. From these findings, it can be concluded that the dimension of self-directedness can reduce the adverse effects of insecure attachment, thereby reducing the risk of addiction to SNS. Moreover, these findings could be a guide for clinicians who can reduce the unpleasant effects of insecure attachment on their lives and relationships by increasing self-directedness in individuals. Also, it can be explained that temperament is the biological and heredity part of the personality, which is organized functionally and have relative stability within various times and situations and includes an independent system for activation, durability, and behavior inhibition in responding to certain groups of stimulants. Research findings indicate that as the temperament dimension of personality traits is the biological and heredity part of the personality and remains stable during time, this personality dimension cannot mediate the attachment style that is a fundamental part of the personality and does not change over time. In contrast, the character dimension of personality is made in the environment. The value system, attitudes, objectives, higher cognitive processes such as abstraction, reasoning, verbal and non-verbal interpretations, language, etc., are related to character. Even character regulates the conflict between different dimensions of temperament, leading to the integrity of personality. As the character is highly acquisitive and environment-formed, it is concluded that the character dimension of personality can mediate the disorganize-ambivalent attachment style.