1. Context

Prostitution is a complex phenomenon. According to its definition, prostitution (a form of sex work) is the provision of sexual services to receive something (goods or services) which is not sexual (1, 2). Over the past decades, prostitution seems to have become a growing global problem (3). In a world where many countries are moving toward idealistic notions, women and girls are being sold like commodities. After drug trafficking and illegal arms deals, sex trafficking is the fastest-growing market (4). Estimating the population size of prostitutes around the world is problematic and ambitious, due to the hidden and marginalized nature of this trade. Nevertheless, a report puts the number of prostitutes at around 40 - 42 million worldwide (5-7).

In addition to the stigma that surrounds sex workers, these women often suffer from being judged and blame for violating social norms (7). The penal code and its implementation often push sex workers to work in the black market, which makes them vulnerable (8). These people suffer from depression, stress, and other mental illnesses. A systematic study showed that 62.4% of the prostitutes are depressed (9, 10). Also, due to legal reasons and social stigma, these people are often deprived of access to health services; hence, they do not receive adequate healthcare. As a result, they are prone to infections such as STDs and HIV to an extent that a systematic study showed 17.3% of the prostitutes in the United States suffer from HIV (11, 12).

Various juridical systems and different regulatory approaches are implemented by governments in order to deal with the problem of prostitution (13). However, these laws and policies rarely achieve their desired effects on prostitution control (7). Initially, in most legal systems, following religious beliefs and common morals, prostitution has been considered as a crime, which by law deserves punishment, but in the nineteenth century, the "Harm Principle" by John Stuart Mill argued that although individual illegitimate relationships should be condemned and harassed by the community, they cannot be regarded as criminals, since they do not harm others. Perhaps in the western legislative system, the discussion of the Wolfenden Committee began in 1957; according to the committee's comments, it was proposed to decriminalize prostitution. The report was approved by parliaments, but the supporters of the natural law, including judge Patrick Devlin, severely criticized this report (14, 15), and argued that freedom of prostitution violates the common morals of society, and society can act to support common morals that have rational benefits. Some individual behaviors affect the community, and society should consider the moral obligation to protect its existence (Devlin), while the weakness of moral constraints leads to the collapse of society (16).

Nonetheless, in countries such as Iran, prostitution is illegal, while Germany, the Netherlands, and several states in Australia are examples of legalization. But, Nordic countries have adopted a (partial) decriminalization approach to sex workers by penalizing the buyers of prostitution instead (8, 17, 18). Different societies react differently, based on values and ideologies. In a qualitative study on prostitutes in the US (where sex work is a criminal offense), they preferred to stay anonyms in order not to “pay taxes and be regulated by the government”, but “being able to seek help when they become victims and to have legal rights” were their arguments frequently used against criminalization (18). Given the response of different societies and cultures to criminalization, decriminalization, or legalization of prostitution, this study aimed to compare the three aforementioned approaches to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of each view.

2. Evidence Acquisition

This study is a narrative review that summarizes various views on how to control the prostitution phenomenon. To conduct this study, related articles in PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases, as well as documents and reports published by Amnesty International, the World Health Organization, and the United Nations Office on AIDS were investigated. There was no time limit for searching the articles and documents. All original articles, reviews, and official reports were included in our searches, but letters, correspondence, proceeding abstracts, and unofficial reports were excluded.

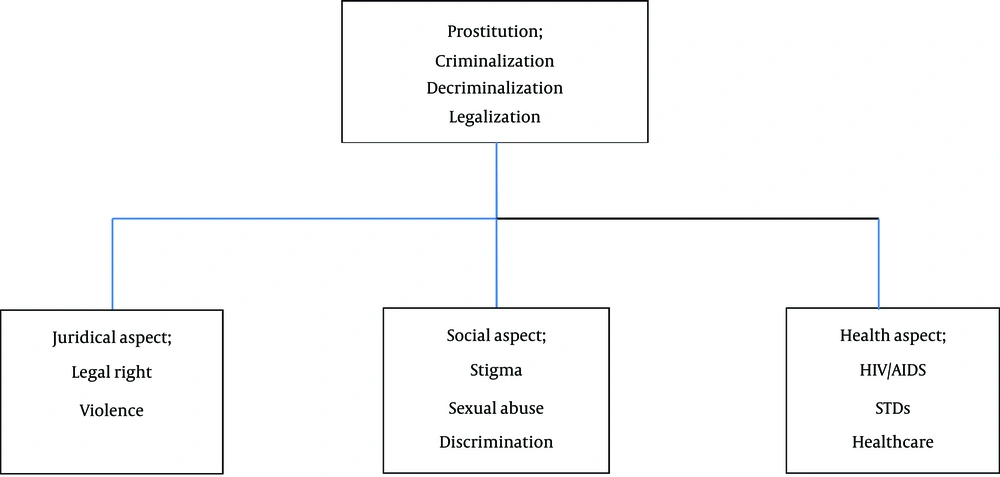

We searched the mentioned databases by combining four sets of related terms: (1) “prostitution” OR “sex workers”; (2) “violence” OR “sexual violence” OR “rape” OR “sexual assault” OR “sex offenses”; (3) “legalization” OR “criminalization” OR “decriminalization”; and (4) “safe sex” OR “condom use” to search titles, abstracts, or keywords until June 2018. Due to different dimensions of the prostitution phenomenon and its consequences, the researchers limited their investigation and selection of articles to the following three areas (Figure 1).

Based on the abovementioned search strategy, 19 out of 163 articles were included in our review. All the included articles were reviewed by HJ, AK, and M.KH, and the results were retrieved based on the keywords and the area of expertise of each researcher. Any disagreement during the selection process was resolved using discussion and consultation.

3. Results

According to the literature reviews and considering the diverse socio-cultural context of the countries, three main approaches, including criminalization, decriminalization, and legalization, are approved to deal with prostitution. In each of these frameworks, human trafficking and child prostitution are criminalized. Each of these approaches mentioned reasons for their theory, which are discussed below.

3.1. The Criminalization Approach

In this approach buying, selling, or brokering (pimping, brothel-keeping, etc.) sex are criminalized (19). Criminalization policies assume that the illegalization of prostitution deters individuals from soliciting or providing sexual services (20, 21). Countries such as Iran and most states of the United States are categorized in this approach (5, 19).

3.1.1. Advantages of Criminalization

The main goal in criminalizing prostitution is not to punish those who engage in prostitution, but to prevent the occurrence of prostitution. Proponents of this approach believe that prostitution is fundamentally incompatible with human dignity, then it must disappear. They claim that the law of criminalization of prostitution seeks the elimination of this incompatibility (22). Based on the proponents’ point of view, criminalization discourages purchasing, reduces the demand for sellers, restricts the size of the market, and may therefore reduce trafficking (19).

3.1.2. Disadvantages of Criminalization

In contrast, the opponents of the criminalization approach claim that the criminalization of prostitution presents the possibility of exposure to violence and abuse. Also, as reported from some states of the United States, the fear of punishment and consequences of prosecution makes it more likely that violence will remain unreported. Violence against prostitutes is associated with misuse or not using condoms and increased risk of STIs, such as HIV (23). Moreover, the punishment strengthens the prostitution stigma by marginalizing the group. Studies show that this group is exposed to widespread human rights violations, including murder, physical, and sexual violence. Harassment by law enforcement and discrimination in access to healthcare and other care services are also commonly reported (24, 25). Another disadvantage of criminalization would be social stigma, discrimination, and gender-based violence associated with sex work that forces a sex worker to continue working in the industry. This discrimination varies according to race, ethnicity, indigenous, and immigrant conditions. There is a distinct overrepresentation of groups who are more likely to be discriminated against, such as, LGBT when viewing the sex worker population (24). Additionally, the criminalization of prostitution tends to further stigmatize its practice and may drive sex workers to operate in a more secret manner, increasing their risk of exposure to violence and abuse. In most instances, these crimes remain unreported or are reported without consequence or punishment of the perpetrators involved (24). Evidently, criminalization reduces the use of condoms since having a condom is evidence of a decision to commit a crime; therefore, people might refuse to use condoms (26, 27). Finally, in the criminalization setting, the likelihood of being abused by the police (such as sexual demands in lieu of arrest) was reported (18).

3.2. The Decriminalization Approach

This approach appears to prompt increased respect for sex workers’ rights and could be a mechanism to reduce violence and trafficking in order to protect the health and rights of sex workers (18, 21).

3.2.1. (Full) Decriminalization

This view refers to the elimination of all laws and penalties which criminalize any part of body in sexual trades. The most typical examples of the full decriminalization approach are New South Wales, Australia, and New Zealand (28).

3.2.1.1. Advantages of (Full) Decriminalization

Several advantages are mentioned for this approach. The decriminalization of sex work would reduce stigma in healthcare settings and communities (29). It protects them against discrimination and violence (30) and provides the possibility to seek support from the health system and law enforcement (18, 22). This framework considers the freedom of sex workers to work individually and/or collectively (24). In this case, the group can have a peer network and use harm reduction techniques. They can obtain rights as workers through building community with other sex workers (18, 21).

3.2.1.2. Disadvantages of (Full) Decriminalization

Besides the above-mentioned advantages, evidence shows some disadvantages to this approach. It defies the principles of equality for women, by leaping from HIV prevention and protection to a call for the decriminalization of buyers of sex, pimps, and brothel owners (30). By (full) decriminalization, prostitution becomes viewed and framed as a regular job, then the impetus to provide any exiting service disappears (31). In addition, this approach seems to increase street prostitution (32). The last critics would be that full decriminalization has not resulted in reduced trafficking victimization, but led to growth trafficking inflows (33).

3.2.2. Partial Decriminalization

This approach decriminalizes the selling of sex, but criminalizes buying it; therefore, criminal responsibility is removed from those who take part in prostitution and places the burden upon those who purchase sex and/or pimp and/or keep brothels and/or other sex establishments. This approach is famous as the Nordic model, which is applied in Norway, Sweden, and Iceland (19, 28, 31).

3.2.2.1. Advantages of Partial Decriminalization

In addition to the aforementioned advantages of full decriminalization, there are additional advantages for partial criminalization. It is assumed that through applying this approach, the prevalence of street prostitution would be reduced without shifting to other forms of indoor sex work (34). This model facilitates partnerships between sex workers and the government in addressing health and safety issues (35). Furthermore, it has had direct and positive effects in limiting the trafficking of human beings for sexual purposes (3, 34). Finally, in this model, the number of buyers decreases, and the local prostitution markets become less profitable (3).

3.2.2.2. Disadvantages of Partial Decriminalization

The opponents of this approach believe that this could increase the likelihood that a prostitute will end up with a dangerous client (28). Due to the ban on brothels, sex workers are unable to work together, which puts them at greater risk (36, 37). Also, this framework in a country increases the number of cases buying sex abroad (28).

3.3. The Legalization Approach

Under legalization, there is a legal market for sex services, but access is restricted by licensing, the operation and management of brothels, soliciting for prostitution, living off the proceeds of a person working in prostitution, and all other sex establishments are under regulation. The legalization approach assumes that sex workers are part of society that cannot be eradicated through criminalization; thus, they should be regulated (38). This approach was designed to control contagious diseases, violence, assault, and other social disorders. Germany is a pioneer for accepting this approach, although Austria, Brazil, and some counties in Nevada apply this approach (39).

3.3.1. Advantages of Legalization

This framework aims to improve the position of sex workers by guaranteeing them the right to choose their work by ensuring their health and safety (38). The licensing system is also enforced by the healthcare system with unobstructed access to brothels (38). In addition, legal measures decrease the risk of sexually transmitted diseases. It also makes the treatment of HIV be conducted in a shorter period. In fact, the legalization brings a level of public security (4, 40). Supporters of this approach claim that the legalization of prostitution makes it easier to identify violence, threats, and abuse of involved people compared to the conditions in which they tend to work secretly and contrary to community culture (41).

3.3.2. Disadvantages of Legalization

Despite the aforementioned benefits, legalized prostitution industries are associated with a higher reported incidence of human trafficking inflows (42). A legalized system of prostitution often mandates health checks only for women and not for male solicitors. Therefore, monitoring prostitutes does not protect them from HIV/AIDS or STDs, per se (43). Evidently, years after the emergence of this approach, it is still not socially acceptable. In fact, legalization might increase the possibility of rejection by family and friends or the possibility of family damage, by becoming aware of their role as a prostitute (44). The opponents of this approach believe that legalization increases the market potential for prostitution. They also claim that classic employers (brothel owners, pimps, traffickers, etc.) in the never-ending drive to increase profit oblige the demands of customers regardless of the harms to the prostitutes (35).

4. Discussion

Prostitution is an ongoing concern for healthcare professionals, philosophers, ethicists, lawyers, sociologists, politicians, psychologists, and NGO activists. As the results showed, this complex multi-aspect phenomenon has its advantages and disadvantages; however, in legislation and policy-making, we must look at the impact of law on various aspects of social life, and we cannot merely focus on one or partial aspects of the law.

4.1. Social Aspect

Sex workers live in the shadow of society, which concerns not only the individuals but also the entire social, economic, and political systems, by illuminating various social inequalities. In the field of legislation, it seems that the difference between the local cultures and beliefs, as well as the impacts of any change on each society, must be considered; however, enforcing a uniform law is not possible, and assuming “international agenda” seems wrong (45). Therefore, Amnesty International's statement on the same program of decriminalization for all societies to control prostitution seems simplistic, impracticable, and inadequate, not taking into account the complexities of this issue. Communities and even prostitutes themselves have different responses to these issues, according to different cultural and social contexts (18). In an Australian study, female sex workers preferred to remain anonymous, despite the legality of sex work in the region, and the reason was the possibility of rejection by family and friends or the possibility of family damage in case of their awareness (44). This indicates that even with the legality of prostitution, the practice is socially unacceptable and could reduce family solidarity (43).

A German study revealed that following the legalization of prostitution, the poverty-stricken people seeking work in the field of prostitution increased (43). However, it seems that the criminalization of sex work to some extent prevented its infiltration into society, but the legalization approach showed some evidence of increased sex trafficking (42, 43, 46). However, partial decriminalization (esp. Swedish model) has planned for a kind of social engineering, for example by changing the attitudes and behavior of buyers, but there is a debate about the results (46-48).

It is expected from any legislative approach to see the entire dynamics of the prostitution phenomenon, not only the prostitute. In that respect, one out of numerous considerations, which require attention, places emphasis on effective multidimensional exiting policy (to encourage and facilitate the process of exiting prostitutes from prostitution); an important aspect that has been neglected by all legal approaches, but in various degrees (Lucas, 1995).

In the legalized and (full) decriminalized area (as evidenced by Germany, Netherlands, and New Zealand) where prostitution becomes viewed as a regular job, the motivation and impetus to provide any exiting service disappear. Also, the criminalization approach is criticized for leading to further marginalization of sex workers, which increases social stigma and leads to victimization. However, sporadic reports from Nordic countries or regional projects, such as Sonagachi, displaying the partial decriminalization approach, suggest the development of an effective exiting strategy and community empowerment (28, 31, 36, 49).

Prostitution is a reflection of society’s structure and family institution; therefore, any legislative model should be aware of these factors that require intensive collaboration between social policy measures and social support systems in order to move towards desirable effects (50-52).

4.2. Health Aspect

Evidently, in the criminalization approach, criminal laws reinforce and exacerbate social deprivation and marginalization of sex workers, which will result in mental illness and the underutilization of health services (8, 37). The exposure to violence and abuse will increase in the criminalization approach, with decreased condom use and increased prevalence of STDs (23, 25, 53). Therefore, according to both partial and full decriminalization and legalization of prostitution, maintaining a prostitute's physical health is more possible. When people are not afraid of having a condom as evidence of being a prostitute for the police, the likelihood of unsafe sex practices and the chances of STDs will be reduced (43). According to previous studies, prostitutes themselves also confirmed this fact and believed that being in a safe environment without a criminalized approach would guarantee their health (54). However, even in the mentioned approaches, health checks for women only and male buyers are not included. Therefore, protecting prostitutes against all types of STDs is not guaranteed (43).

Regardless of each approach to the prostitution phenomenon, prostitution is not socially acceptable in many socio-cultural contexts, so providing required healthcare for them would be complex (55, 56). On the one hand, they prefer to be anonymous due to stigma and discrimination, and on the other hand, they have a right to equal access to healthcare (57, 58). Furthermore, they need more regular care to be checked not only for STDs and blood-borne diseases but also for any mental or other physical problems (59). Therefore, providing a comprehensive healthcare strategy for them could be at odds with a state-wide approach towards prostitution itself (60).

4.3. Juridical Aspect

It seems that looking at the sex working phenomenon through the lens of legal doctrine shapes the subject too narrowly and is a kind of reductionism. In this regard, law (and legal complex), rather than altering and changing social life is a part, although a key part, of wider processes that constitute it. Even in a postmodern approach, it believes that law and money play key structuring roles, but prostitution is contingent on cultural, economic, and social factors. In today’s societies, insufficient critical legal work has been developed in this field to focus on legal rules, their shortcomings, and how the law operates. Finding out that law could be “a mode of regulation” as well as “a tool of resistance” or in other words “the law is a machine which oils the modern structures of domination, or which, at best achieves a tinkering on the side of justice” allows for holistic and nuanced insight of legal rules’ roles and status in complexities and regulation of commercial sex and emphasizes the need for an interdisciplinary approach (13, 61, 62).

It appears that there are conflicting reports on the impact of legislation away from criminalization on the reduction of violence against prostitutes; there are other reports of failure of these projects and an increase in women's prostitution and trafficking, and the studies showed contradictory results (4, 37, 41, 43, 46, 63, 64). In this study, researchers from various fields of law, ethics, health policy, and community medicine participated. Therefore, various aspects of approaches to the phenomenon of prostitution were examined.

4.4. Conclusion

Examining each legal approach to prostitution reveals that this area of the law is extremely complex, and one cannot adopt or prescribe a single approach to be enforced in every society. The selection of an appropriate approach for each country is multifactorial, including the economic, social, and cultural conditions, as well as individual and common social interests. Although it seems that partial decriminalization has greater benefits with fewer disadvantages, given that the subsequent preservation or creation of laws against smuggling and sexual offenses is required, the decriminalization approach is not without flaws.

As with any theory of rights, there is a huge gap between law and practice. In these circumstances, more communities must consider reducing the adverse effects of prostitution. In this regard, although there is a legal ban, countries can take control of the extent of the complications by considering some of the mentioned solutions. All countries, with any dominant approach and any socio-cultural context, must respect the human rights of prostitutes and improve access to healthcare facilities, through mobile teams and/or voluntary counseling and testing. The most crucial step is to empower prostitutes, by allowing them to remain anonymous and safe by developing an effective exiting strategy. Using the moderator rules that are embedded in the laws of each country for expediency, it may also be possible to reduce the harmful consequences of the first rules, or measures can be taken by considering specific rules and regulations that exist in the national system of each country.

The present study has some limitations such as the lack of access to articles published in languages other than English and well-known limitations of narrative literature review. Also, performing qualitative studies within the group of prostitutes and analyzing their experiences and perspectives in different contexts will better clarify the differences between the underlying factors and the attitudes of the groups involved in this phenomenon in order to provide a more accurate judgment of each approach. Further studies would be needed in this regard.